By Dave Donohue

Emergencies, whether large or small, have their own information stream. How emergency services agencies manage the information stream can bolster the agency or reduce it to a meaningless sideshow. Fire and emergency services leaders must be aware that information about emergencies will be distributed, whether they are involved or not. To better serve their communities and their organizations, managing information is critical to success during and after the incident.

Emergency Information

For the community, emergencies are periods of high stress that alter the way information is received and processed, requiring that communication styles should be altered in order to be effective. First, during periods of high stress, the ability to process large amounts of information is significantly reduced and the ability to distill meaning is hampered, leading to misunderstanding of risk, actions, and other factors. To address this, emergency messages should be simple and short, focusing on key information using non-technical terms. Second, when messages conflict with daily reality, other agencies, or individuals, members of the community will hold on to their traditional beliefs and paradigms. At this point, rumors and especially the opinions of trusted individuals are seen as valid and correct regardless of evidence and any information that differs is often discounted. As message conflict becomes apparent, individuals will continue to seek out information from official and unofficial sources. Finally, greater credibility is given to the first message regarding the emergency incident. This requires additional work and messaging to overcome any misinformation associated with the first message received.

RELATED

Controlling Communications During a Critical Incident

Safety Officer Drill: Incident Communication Red Flags

Social Media Concerns During Emergencies and Incidents: Lessons from a Recent Tragedy

Communications Broke Down: An Excuse for a Serious Problem

How We Process Messages During a Crisis and How We Can Make Emergency Messages Stick

| We simplify messages and information | We only hear part of what is being sent, our memory is impaired due to stress, and we are prone to misinterpret information | Use simple messages, avoid technical jargon, and repeat critical points |

| We hold on to current beliefs | We discount information that conflicts with what we believe to be true and we refuse to believe evidence that is in conflict with what we believe | Use credible sources for delivering truthful, fact-based, specific messages and provide positive actions that can be taken |

| We seek additional information and opinions | We look at different sources for information, we call others, and we search the Internet seeking facts and opinions | Use consistent messages that are coordinated and released from trusted partners and stakeholders |

| We believe the first message that we hear | When we are confronted with unique situations and emergencies, the first message about the situation sticks | Release credible, fact-based, verified messages as quickly as possible and work with other partners and stakeholders to release similar messages |

Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014

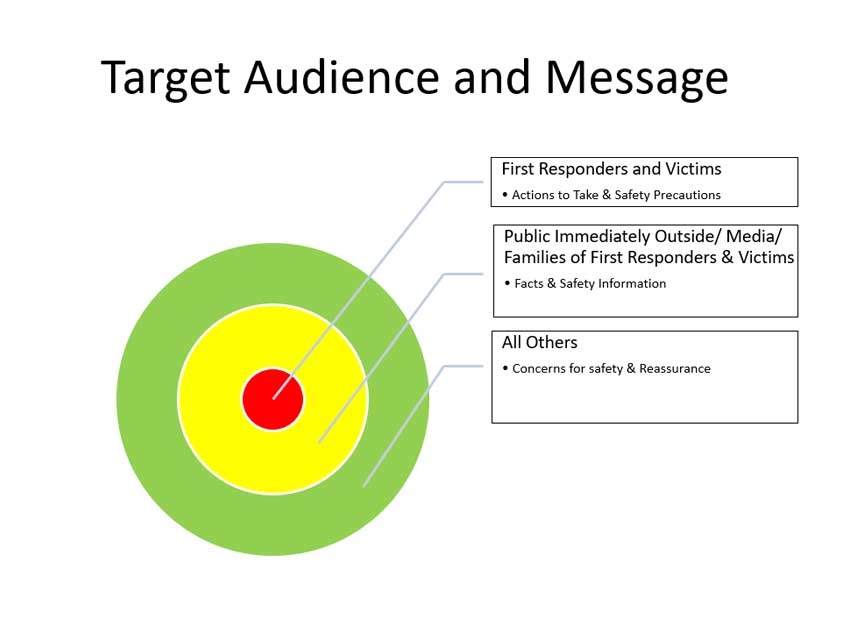

When crafting information to be released, consider three audience groups that should be addressed. The first group consists of those who are directly impacted by the emergency incident. This includes victims, emergency responders, and associated groups such as hospitals. The information needed relates to actions that they can take and safety messages. The second group consists of those individuals located directly outside of the impact area, the media, and the families of victims and responders. Messages and information for this group is focused on the facts of the incident, safety precautions, and limiting any actions that they should take. Finally, information and messages for everyone not already identified should address safety concerns and provide reassurance that actions are being taken to mitigate the incident.

Communication Planning and the Incident Communications Cycle

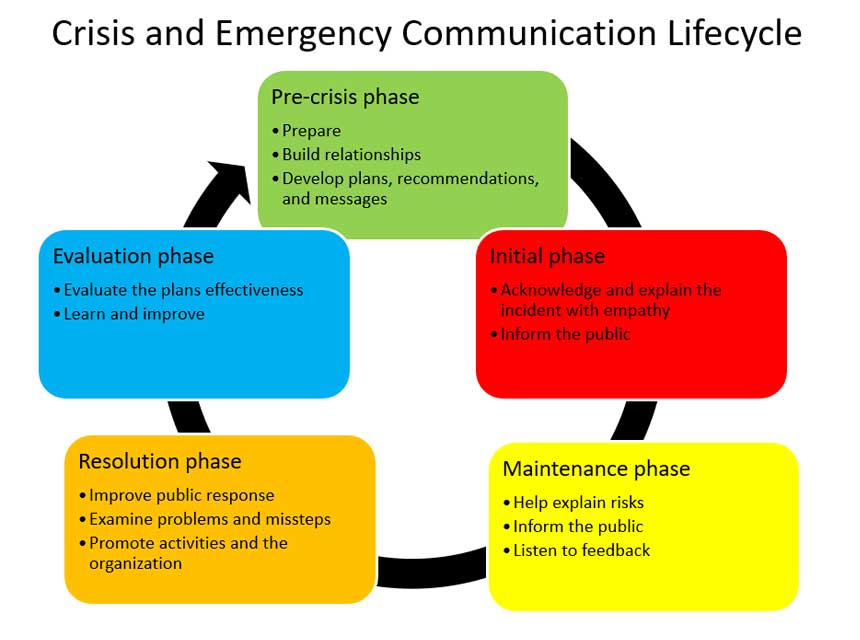

To effectively manage communications during an emergency, develop a communications plan to guide actions during the five phases of the emergency communications lifecycle. Build the plan during the pre-crisis phase. It should consist of general guidance and instructions for communications that can be tailored to any incident type. The plan assigns actions and responsibilities; contains contacts for stakeholders, including the media; coordinates procedures; and describes how information will be shared and vetted. The plan is reviewed, endorsed, and signed by senior leadership and representatives from partner and stakeholder groups, ensuring their familiarity with the plan and how it will operate. Once the plan is finalized, it should be reviewed and exercised on a regular basis to ensure currency and identify and correct areas of deficiency or weakness. Other activities that take place during the pre-crisis phase include building collaborative teams across disciplines, developing consensus recommendations, crafting and testing messages, and ensuring organizational and community preparedness for all community hazards and risks.

Common Elements of a Successful Emergency Communications Plan

- Describes how the situation will be verified

- Substantiating facts

- Addressing rumors

- Identifies how parties will be notified of the incident

- Identifies how the plan will be activated, how situational awareness will be gained, and how a common operating picture will be shared

- Describes duties, responsibilities, and authorities of individuals and organizations

- Describes how information will be gathered, formatted, approved, and released

- Describes how information about performance will be collected and reviewed and how improvement processes will take place

- Describes how efforts to educate the public about emergencies will occur

- Describes how daily events will be monitored

- Describes how and when joint information centers will be established

- Identifies the process for designating spokespersons and subject matter experts

Once an incident occurs, the initial phase has begun. During the initial phase, agencies will begin to gather and confirm information for release to ensure that it is factual, determine the level of communication that is needed, and coordinate the response to the incident. When vetting information and determining what information needs to be released, begin by ensuring that the information is accurate and contextualized. Separate truthful facts into “need-to-know” and “nice-to-know” categories. During the initial phase, the focus will be on need-to-know information. This information is generally related to safety, initial actions that are being taken, and actions that can be taken by those in the emergency area. Once the need-to-know information has been assembled and formatted, if possible, have the document checked by at least three people for accuracy. These editors should include someone responsible for the organization’s reputation, the policy director, and a subject matter expert. In addition, it is important to share the document with involved stakeholders prior to release to ensure accuracy and consistent messaging and as a courtesy. Once the document has been determined to be accurate, release should follow the guidance within the communications plan and organizational directives. The release should acknowledge the incident, provide empathy and information, and establish credibility for the response.

Initial Phase Communications

| Objectives | What the public wants to hear |

|

|

Initial Message Recommendations

- Keep the target audience in mind

- Convey empathy

- Be prepared

- Be honest and truthful

- Provide short, concise messages that are limited in detail and laser focused

- Provide information that is immediately relevant

- When giving actions to be taken, give them as actions to do, not actions to avoid (for example: ” stay indoors” rather than “do not go outside”)

- Repeat the critical items of the message

- Create action steps in groups of three or four or make an acronym (for example: “to improve your cost recovery rate for FEMA Public Assistance tell us what you did, what you used, when you did it, and who did it” (four items)

- Use personal pronouns for the organization (for example: “we contained the spill”)

- Avoid technical jargon

- Don’t fill with unnecessary information

- Don’t guess or assume

- Don’t be condescending or judgmental

- Address the problem, not the people

- Promise only what you are sure can be delivered

- Don’t discuss cost or liability

- Don’t apologize

- Don’t use humor or smile. Use appropriate emotions

- Dress professionally when presenting

- Don’t be overly graphic in discussing the emergency

With time, there will come a point where the incident is ongoing but most or all the direct harm has been contained. This is known as the maintenance phase. During this phase, communications should focus on helping the public understand their risk, both from the incident and from a similar incident reoccurring in the future; providing background information on what happened, how it happened, the history and probability of future incidents, and recovery operations; generating support for response and recovery efforts; explaining recommendations for preventing or mitigating future incidents; and empowering risk-benefit decision making for the community and policymakers.

The resolution and evaluation phases begin the process of moving into the future. The resolution phase looks to improve public awareness of risk and their role in prevention, mitigation, and response while also looking at the emergency response for successes and areas for improvement. This phase also seeks public support for policy and resources to mitigate, prepare, prevent, and respond to future incidents while also promoting the actions and abilities of the organization. The evaluation phase builds on the actions of the mitigation phase to develop preincident plans, acquire resources, and prepare for future emergencies based on the lessons learned and improvement planning process of assigning responsibilities for improvement. This phase also links with the pre-crisis phase, completing the cycle.

*

Communicating with the public and the media is stressful for most emergency services personnel. Failing to communicate messages in a way that the public and community can understand and act upon limits the community’s ability to respond and recover and prepare for future incidents. Emergency services leaders should include communications planning as a critical factor in successful organizational management, as an effective risk-reduction strategy, and as a conduit for ensuring that the organization has access to the resources, partnerships, and community involvement it needs to succeed in the future.

EPA’s Seven Cardinal Rules of Risk Communication

| Rule | Guidelines |

| Accept and involve the public as a legitimate partner |

|

| Listen to the audience |

|

| Be honest, frank, and open |

|

| Coordinate and collaborate with other credible sources |

|

| Meet the needs of the media |

|

| Speak clearly and with compassion |

|

| Plan carefully and evaluate performance |

|

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Crisis Emergency Risk Communication. US Department of Health and Human Resources, Washington: DC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Keeping the US Prepared and Ready to Respond to Public Health Threats. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/index.htm

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). EPA’s Seven Cardinal Rules of Risk Communication. https://archive.epa.gov/care/web/pdf/7_cardinal_rules.pdf

U.S. Forest Service. (2020). Public Fire Information Website. https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/fire/information

Seeger, M., Sellnow, T, & Ulmer, R. (2003). Communication and organizational crisis. Westport: CT

U.S. Coast Guard. (2014). PIO Job Aid. https://homeport.uscg.mil/Lists/Content/Attachments/2916/PIO_Job_Aid-May2014.pdf

About the author

Dave Donohue is a 40-year veteran of emergency services and has served with emergency services, fire departments, and EMS agencies in Florida, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. He resides near Hagerstown, Maryland and is the owner of Mid-Atlantic Emergency Services Consulting. He works for a fire-EMS educational institution in Emmitsburg, Maryland, is an adjunct instructor for the Maryland Fire and Rescue Institute, and is a member of Community Volunteer Fire Company of District 12 in Fairplay, Maryland. He can be found wandering the stands of Hagerstown Municipal Stadium during the minor league season or reached at dkdonohue@aol.com.