By Jason Hoevelmann

Although common, garage fires do not always receive the same attention as other fires to which we respond. After all, occupied spaces in homes and other tenable buildings have a significant life safety component that can easily be overlooked in garages. However, responding firefighters and officers need to consider risks and critical decisions that attached garage fires entail for successful operations. This article discusses some of the risks and operational considerations for attached garage fires in residential buildings.

An attached garage is an enclosed space designed for parking vehicles and storage that is attached to an occupied residence. It comes in different shapes and sizes and presents many risks for responding firefighters. Firefighters and officers must not let their guard down or become complacent when responding to attached garage fires.

The attached garage began as a small structure in which to park a single vehicle and had limited storage. Over the years, it has grown into a structure with the capacity to accommodate several vehicles, with multiple overhead doors and a large storage capacity for tools, gardening equipment, and anything else owners don’t want to keep in the house. Along with the ever-growing size of attached garages and their storage capacity, many may include a living space above that is separate from the main house.

As at a working house fire, we must do a complete and accurate size-up at such operations. These structures aren’t just garages anymore; they can involve increased risk and complexity. This is especially important with the attached garages that include extra features and uses.

Preplanning and Size-Up

As with any fire, the size-up begins before the call. It is important to have a working knowledge of the subdivisions and building characteristics in your response area. Every fire department has areas with unique building designs that can cause some special hazards.

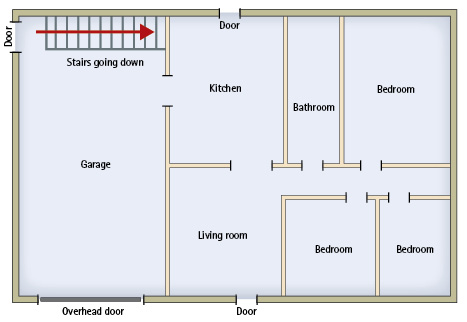

Figure 1. Basement Access

The stairs provide the only access to the basement, which is under the living room. (Figure by author.)

For example, in my initial response area, some homes with small attached garages were built in the mid-1940s and early 1950s. As originally designed, these homes had full basements with stairs from the garage on the Charlie side as the only access. If unaware of this, firefighters may look for the basement stairs in the interior above a basement fire and won’t find them. This will take valuable time and allow a basement fire to grow, increasing the risk of the floor above collapsing. Most homes don’t have this hazard; but, if not considered, it could prove to be a huge hazard for crews who may operate in the garage during firefighting and overhaul (Figure 1).

Ideally, during the size-up, you want to find the fastest way to get water on the fire. Looking for an exterior entry door into the garage will decrease the time needed and enable you to protect the integrity of the door between the garage and the house. Additionally, look for signs that indicate the presence of living or other usable space above the garage. Some of those spaces will be a part of the home, such as bedrooms or bonus rooms (extra rooms used for various purposes), and some may not be connected to the home, with a separate set of stairs inside the garage. In either case, consider life safety and fire spread.

With many new homes and additions, owners have built living space (often master bedrooms) directly above the attached garage. This creates obvious challenges for the first-arriving officer. As with any fire, consider size-up indicators, including the time of day. These occupied spaces above the garage are at risk for smoke and fire spread. The size-up indicators will determine whether companies start with a search or attack the fire.

The size-up plays a critical role in decision making on initial operations. That first-due company has a lot of data to gather and decipher to make the best decision.

Don’t hesitate to open the residence’s front door to evaluate the interior conditions. What you find may affect your decision making for initial actions.

(1) Garages are commonly used for impromptu storage units and can contain heavy fire loads. This not only makes the fire content heavy but also can make access extremely difficult. (Photo by author.)

Exterior or Interior Attack

You’ve done a complete and thorough size-up, and it’s time to deploy. The company officer has to decide whether to apply water to the fire from the exterior (through the garage entry door, the overhead garage door, or a window) or to take the initial line to the interior. It depends on the conditions you find on arrival and the available resources. Additionally, consider the search profile items, such as the time of day, the presence of occupants in the front yard, whether the interior presents an immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) atmosphere, and whether there are occupied spaces above the garage.

With those considerations, ask, “How can we have the biggest positive effect on the fire?” In most cases, by putting water on the fire as quickly as possible. It’s not about interior vs. exterior or transitional. It’s about the factors that contribute to our success.

Over the past 40 years, most homes have been built with some degree of code compliance. But even in areas without residential building codes, as a best practice, a contractor would install a 20-minute fire rated door in a new house between the garage and the residence. The fire service knows the dramatic effects of keeping a door closed and compartmentalizing the fire area.

Additionally, in newer homes that have built space above the garage, a fire-rated barrier, normally with a one-hour rating, should be between the garage ceiling and the floor of the above space. As you know, such barriers are not always well-built and their integrity may not have been maintained over the years. But they are effective in keeping fire from spreading as quickly as it would without them.

If you are to immediately take the initial line to the front door and make your attack from the inside, you must break that barrier to make your attack, which puts you at a disadvantage for two reasons. First, you don’t fully know the volume of fire you are attacking. Second, there is a risk of fire and superheated gases making their way into what was a protected space, filling uninvolved areas of the home with smoke. This can hinder search teams and any evacuating occupants.

Sometimes going to the interior is the best option. But even then, be aware of what you are doing to the interior environment by making an interior attack. If it is to protect the egress route and the search teams, you might advance the line to protect those interior exposures and keep that door connecting the garage to the house closed.

By holding the interior position without opening the door from the garage to the residence, you can put an inspection hole in the ceiling to confirm that fire hasn’t breached the wall between the garage and the house and you can help to maintain that door’s integrity, limiting or eliminating fire, smoke, and gases from entering the residence. If choosing this tactic, a second line should be working from the garage side to start extinguishment as soon as possible.

Overhead Door Entry

Not every attached garage has an accessible entry door or window to the garage itself, so the overhead door is the primary access from the outside. Getting through the overhead door can be a challenge, depending on its age and type and whether it has an automatic door opener. Such challenges may determine whether you choose to go to the interior to make the attack. If you find a stubborn overhead door, you must first unseal that barrier to get some water on the fire.

First, cut a triangle opening just big enough to admit the nozzle and begin extinguishment by cooling and slowing down the fire as a larger cut or access is made. This tactic is relatively successful, doesn’t take much time, will significantly slow the fire, and will provide good knockdown. This buys crews time to fully gain access from the outside or to finish from the interior.

As a second option, make a panel cut or a larger triangle cut that you can peel back enough to make an attack from an exterior position. Again, you can make a significant knockdown and slow or stop the fire’s progress. Although this is a common tactic, crews must have the right equipment to make the cuts quickly.

(2) Garages in these split-level homes provide a high potential for exposure to the sleeping rooms above. The need for a rapid search in these occupancies is paramount. (Photo by author.)

For crews without rotary saws on every apparatus, another option for some overhead doors is to pry a small opening from the side or the bottom. It’s not as easy or as effective as the options described above, but you can use a pry bar to pry an opening just large enough to insert a nozzle and start extinguishing the fire in the space. This is not as effective because the stream cannot be manipulated as well; depending on the type of door and its frame, it may not work at all.

One overlooked but simple and effective method is to use a sledgehammer. First, know what type of door you are working with; otherwise, you will be swinging a while with no result. Many new doors are made of insulated panels enclosed in lightweight metal. By swinging a maul or sledgehammer, you can knock a panel out or, if you swing near the rails, you can compromise the rollers enough to create some space for a nozzle.

Note that many new rollers for residential overhead garage doors are made of nylon. When exposed to high temperatures during a garage fire, those rollers may melt and be compromised enough to enable you to just push a portion of the door inward. In any case, “try before you pry” is relevant for overhead garage doors as well as conventional entry doors. However, you need to consider these nylon rollers when the door is up, too.

(3) The importance of fast water and ensuring the integrity of the interior door is critical to contain and limit fire spread into occupied spaces. (Photo by Andrew Kingsbury.)

In other cases, you can simply raise the door on its tracks. Use caution when entering the garage after raising the door, especially with heavier doors. There have been instances in which firefighters making an attack into a garage through the raised overhead door had the door come down, trapping them in a heavily involved garage fire.

To prevent this, one frequently used but possibly the least desirable method is to use a pike pole or broomstick to hold the door up. There is just too much going on around that thin, unstable pole for it to be secure. Too often, we have witnessed it getting bumped by hoselines and crews moving in and out of that space.

Some better options include the following:

• Use locking pliers or clamps high up on the rails to prevent the rollers from tracking all the way down.

• Use the fork end of a halligan to bend the rails to prevent the door from tracking down [a tip from Lieutenant Sam Hittle, Wichita (KS) Fire Department].

• Use an A-frame ladder to keep typical residential overhead garage doors from tracking back down. Although it is stable, it, too, can be bumped and is not always practical.

Removing the entire door or as much of it as possible during fire operations and overhaul is the most secure way to ensure that it doesn’t come down. Remember that even with the door fully raised, when exposed to extreme heat and fire operations, it is an overhead hazard that can fall on firefighters. Don’t fall into the trap of believing that since the door is up and out of the way it is no longer a problem.

Contents Hazards

Attached garage fires can offer many easy-to-overlook hazards. Along with the overhead doors, garages can be full of the following hazards: flammable/combustible liquids, guns, liquefied petroleum gas tanks, and anything else. Keep these possible hazards in mind, and consider the use of foam when operating and attacking these fires.

Considerations

Consider the following at all attached garage fires:

• Always protect the interior, including keeping the door between the garage and the residence closed.

• Don’t walk past fire! Extinguishing the fire as quickly as possible will protect the interior and limit fire spread.

• If an interior attack is required, maintain the integrity of the door between the garage and the residence.

• With areas built above the garage, consider the threat of autoexposure and smoke/fire spread. Access may be difficult if it is available only from the interior of the garage (studio areas).

• Expect unknown hazards, such as gasoline, oil, liquefied petroleum gas tanks, and large quantities of stored materials.

• Be as expedient as possible in getting access to the garage for extinguishment when the interior of the residence is not immediately compromised.

• Match your forcible entry training for accessing garages to your capabilities and resources.

• Use secure methods of controlling the overhead door.

• Look for entry doors to the garage for access, even if it requires taking the line a little farther out of the way.

• Consider special hazards—sublevel garages with heavy loads above, stairs to basements, and so forth.

Garage fires present their own special challenges, but the well-armed officer and crew will ensure success by performing a complete size-up, getting water on the fire quickly, and protecting the residence’s interior spaces. Be patient and deploy appropriately based on the conditions you have found, your resources, and your department’s standard operating guidelines.

JASON HOEVELMANN is a 25-plus-year veteran of the fire service and has been instructing for more than 20 years. He is a career battalion chief with the Florissant Valley (MO) Fire Protection District in North St. Louis County. He is a co-owner of Engine House Training, LLC, providing hands-on training in firefighting operations and safety and survival.