Atlanta’s Hotel Winecoff Fire Worst In Nation’s History

City’s Failure to Heed Safety Lessons of Other Hotel Fires in U. S. Results in 119 Dead, 100 Injured

EDITOR’S NOTE: When two fires within four days of each other last June brought death to over 80 persons and injuries to 200 others, in the LaSalle and Canfield Hotel holocausts, students of fire protection and prevention were inclined to believe that the shocked nation had learned its fire safety lesson and that from this peak of destruction in this classification there would be a decline as remedial and corrective measures were taken to make further such tragedies impossible.

Now fire has struck again—and again, to drive the ghastly record of destruction to still greater peaks. On December 7 the 33-year-old Winecoff Hotel in Atlanta was ravaged, causing the death of 119 persons and injuries to over 100, some of them firemen. Two days later 11 others died and 18 were injured in the blaze-gutted Barry Hotel, in Saskatoon, Canada.

On every side government, state and municipal officials are joining with the man-in-the-street in asking “why must these things happen!”And not a few of them are directing their inquiries to the fire service which, more than any other entity, is closest to these catastrophies. In our endeavor to report these fires fully and accurately, we have had the unselfish cooperation of many of the officers and men of the service who participated in the fights against these fires, as well as correspondents and others who were eye-witnesses of the struggles.

This account is so epochal and has so much of importance to the fire service that we have elected to allot to it more editorial space than this, or any other journal of the fire service, has ever before devoted to a single fire.

Whatever merit our readers may find in this account of the Winecoff and Barry tragedies is due in large measure to the cooperation of the National Board of Fire Underwriters; members of the Atlanta and Saskatoon Fire Departments and to other casual and consistent contributors and correspondent who likewise may recognize their thoughts, if not their names in the following.

IN the worst hotel disaster in the nation’s history, during the early hours of Saturday, December 7, fire raged through the 15-story, 33-year-old (advertised “fireproof”) Winecoff Hotel in downtown Atlanta, resulting in the deaths of 119 persons and injuries to approximately 100 others, many of them firemen.

The deaths were forty-eight more than the previous record number of seventy-one hotel fire deaths in the burning of the Newhall House in Milwaukee, in 1883, and almost twice as many as perished in the June catastrophe in the LaSalle Hotel in Chicago.

Lending emphasis to the tragedy is the fact that it came at a time when, with the Hotel LaSalle and the fourday later Hotel Canfield fires in mind, almost the entire country’s safetyminded citizenry was engaged in the preparation and enactment of laws to outlaw such disasters., And ironically, it followed repeated warnings sounded by Atlanta newspapers subsequent to the LaSalle and Canfield fires that Atlanta could have such a tragedy. Last June, readers of the Atlanta Journal were told in a series of articles of “800 fire hazards” in Atlanta and that “Three-fourths of the Hotels” in that city were called “Fire Hazards.” At that time, the city’s Fire Marshal, Harry Phillips, pointed out that approximately 10,000 people sleep in Atlanta’s hotels every night. Seventy-five per cent of these hotels, because of their age and wooden type interiors, constitute a very senous tire hazard.” The papers reminded Atlantans of the burning of the Terminal Hotel in their city on May 16, 1938. with loss of thirty-five persons.

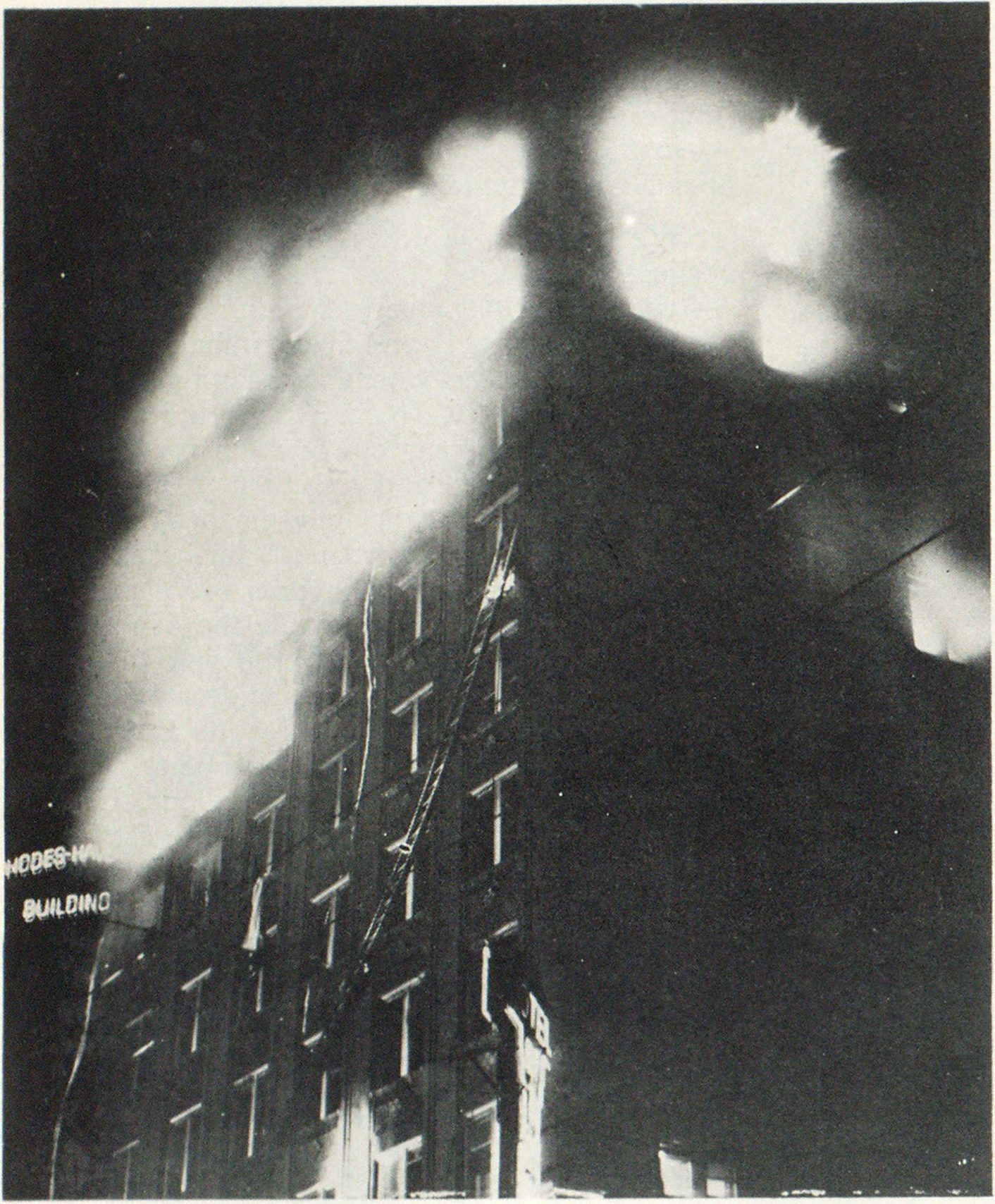

Fig. 1. Extent and Degree of Fire at Its Height Scene about 5 A.M. showing northeast corner of hotel with eighth to twelfth floors heavily involved. Many persons below the eighth floor were saved by fire department ladders. Fire later extended to upper floors. Fire was extinguished about 6:30 A.M.

The Winecoff Hotel itself had a gyim prelude to the disaster about lour years ago when a fire trapped guests on the upper floors. On this occasion, although the fire damage was small, there was near-panic. Several frightened guests crawled out on the fourteenth-floor window ledge; many hung out of their windows screaming for help, and others climbed across ladders to safety in the windows of the adjoining Mortgage Guarantee Building, wheye building employees and firemen rescued scores.

Thus was the stage set for the final tragedy of December 7.

Built in 1913

The Winecoff Hotel is located on the southwest intersection of Peachtree and Ellis streets on the highest eminence of downtown Atlanta.

The hotel was built in 1913 by the William A. Fuller Company of New York. The architect tvas W. L. Stoddard, also of New York. The cost at the time it was built is understood to have been in excess of $350,000. Realty men estimated the value of the property before the fire at front $750,000 to $1,000,000.

The hotel occupies a plot 63 by 70 feet at grade, with the main entrance and mayquee on Peachtree street. It is fifteen stories (approximately 155 feet) in height, with full basement and small sub-basement. The floors are numbered from one to sixteen but, as is the case in many hotels, there was no “13th floor,” it being omitted, out of deference to the superstitious, from the numbering system. The top floor was known as the sixteenth.

Originally the hotel contained 200 guest rooms, but at the time of the fi.re the number was reported as 194. On the morning of the fire the hotel was practically filled to capacity with a stated 300 guests. Many of the guests were permanent residents and some of these were elderly persons.

The construction, classified at the time as “fireproof,” included protected steel frame with roof and floors of concrete on tile filler between protected steel beams and girders. Dividing walls between rooms are of hollow tile, plastered on both sides. Exterior walls are twelve-inch brick panel type.

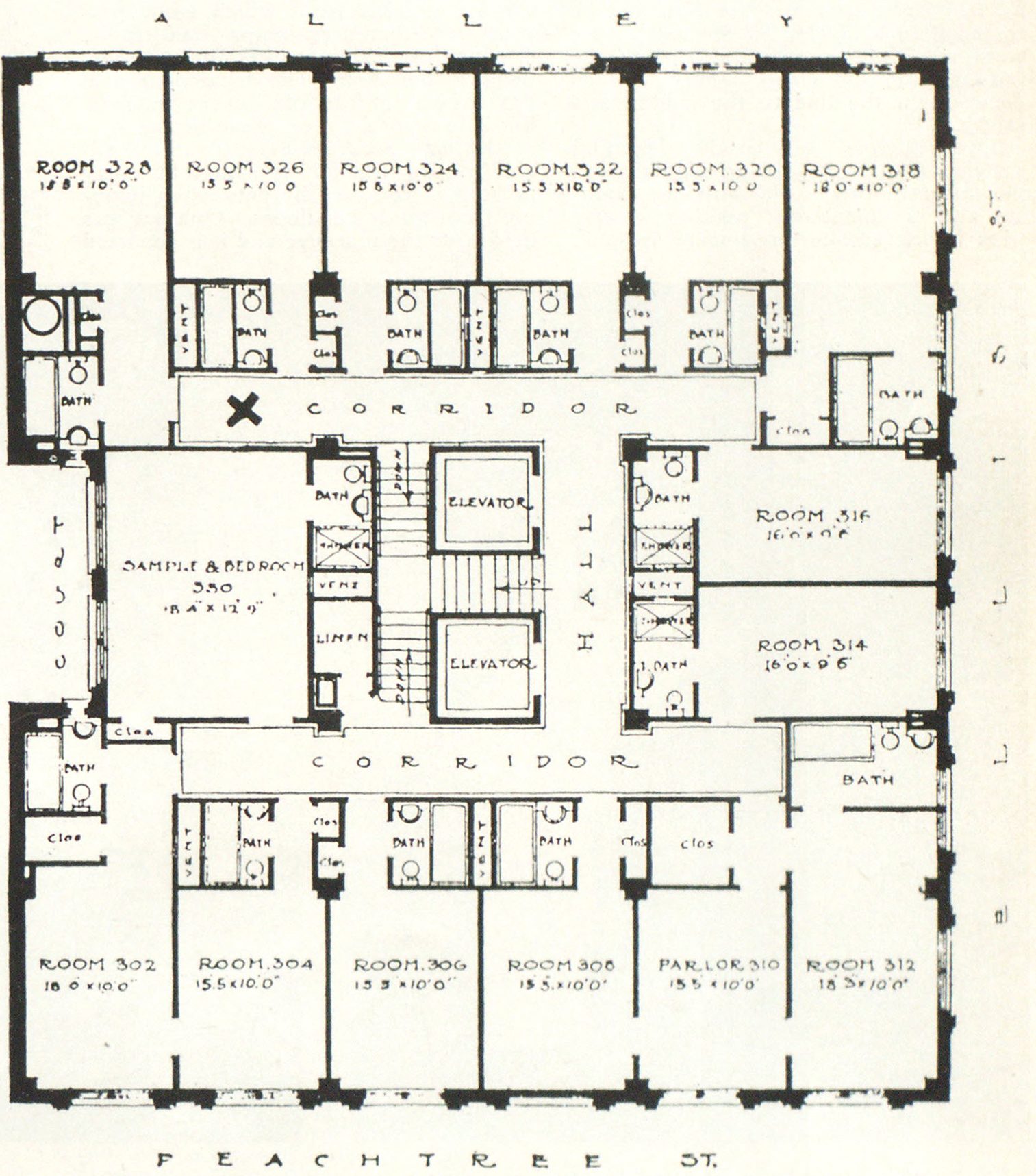

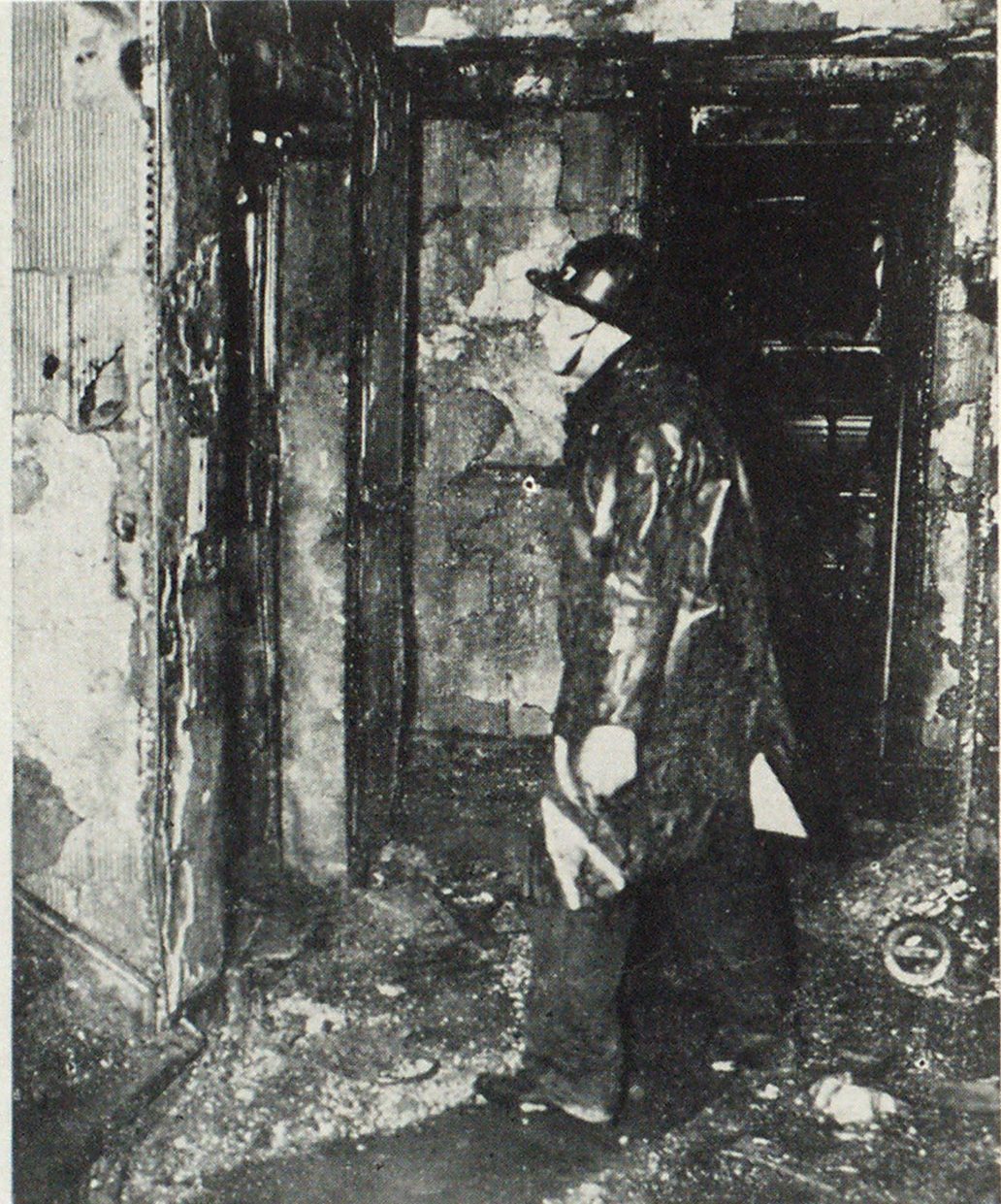

The main floor openings (see Fig 6j are in a single group and consist of two elevator shafts, extending from basement to penthouse on the roof, with stairway between these shafts, extending the full height of the building, from basement to top floor. The elevator shafts are enclosed in tile with openings to enclosure on each floor protected by metal doo.rs having large wired glass panels.

The stairway was not enclosed: a fact that should be kept in mind in any study of this fire. Starting with the mezzanine, or second floor, it rises between the elevator shafts, to a landing half way up to the third floor and then branches out with two wings rising the remaining distance, one wing to the east behind the east elevator enclosure, to the corridor on the east side of the third floor, and the other wing to the west, behind the west elevator enclosure, to the corridor on the west side. This same arrangement continues from the third floor to the top or fifteenth floor, with single risers half way up from the lower floors and branching out into two wings each leading to a separate corridor on the floor above. There is a small enclosed stairway extending from the fifteenth floor to the roof, having an ordinary wood door on enclosure on the fifteenth floor.

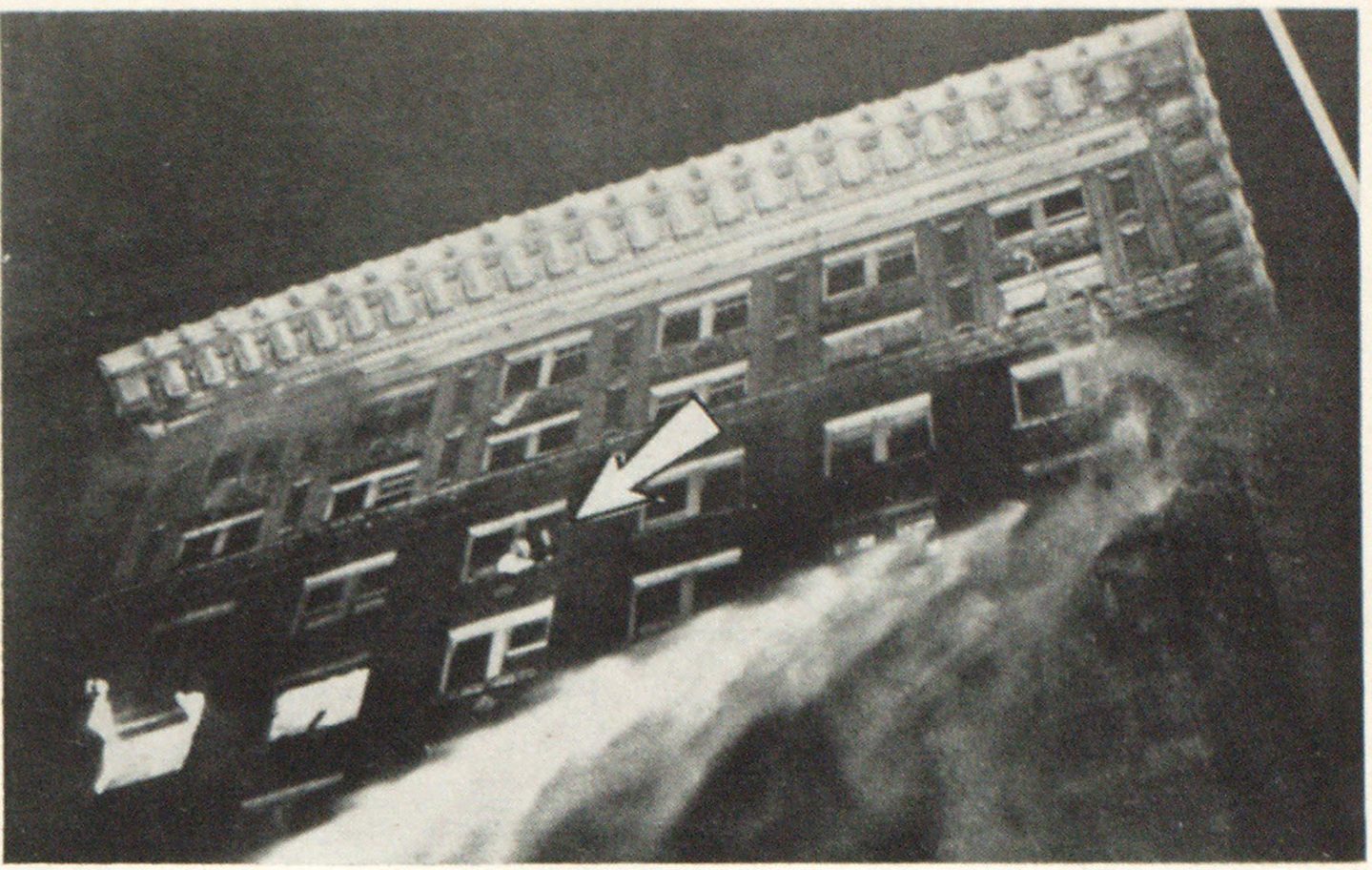

Fig. 2. Fire Department in Race with Death While two of many guests trapped on upper floors of burning Winecoff Hotel prepare to lower crude sheet-rope, fire department streams are employed in effort to drive back flames which have control of floor below. Heaviest stream is being directed from across Ellis Street. Note: Corner rooms on three top floors at right were scene of heroic rescues.

It should be repeated that the above elevators and the single open stairway are the only means of egress from the third floor and all the floors above. According to a statement of the National Board of Fire Underwriters, two separate stairways, each fully enclosed, would be required for this building by the Board’s Recommended Building Code.

In addition to the above described openings, there is a small open stairway from the sub-basement to the mezzanine, located in the southwest corner, and seven small pipe or vent shafts, the latter being enclosed with tile and having wooden doors on small openings into the corridors and also small, unprotected vents into bathrooms. It is said these smaller openings were not a factor in the spread of this fire.

Corridor Walls and Stairways Had Painted Burlap

The walls of the corridors and stairways were covered with painted buckram or burlap from the wood baseboards to small chair rails about four feet above the floors; from this chair rail to the ceiling the walls were papered; also, there was a small wood picture moulding near the ceiling. Ceilings were painted. The corridor floors were completely covered with carpet on felt padding.

The stairways were steel with composition tile wearing surface. The doors to the guest rooms were light panel wood type, with wood frames. All corridor doors except those in closets had transoms. These were originally the usual plain glass set in wood frames, but subsequently the glass had been removed and replaced with wood. These doors and transoms should be considered together with the open stairway in evaluating the spread of the fire.

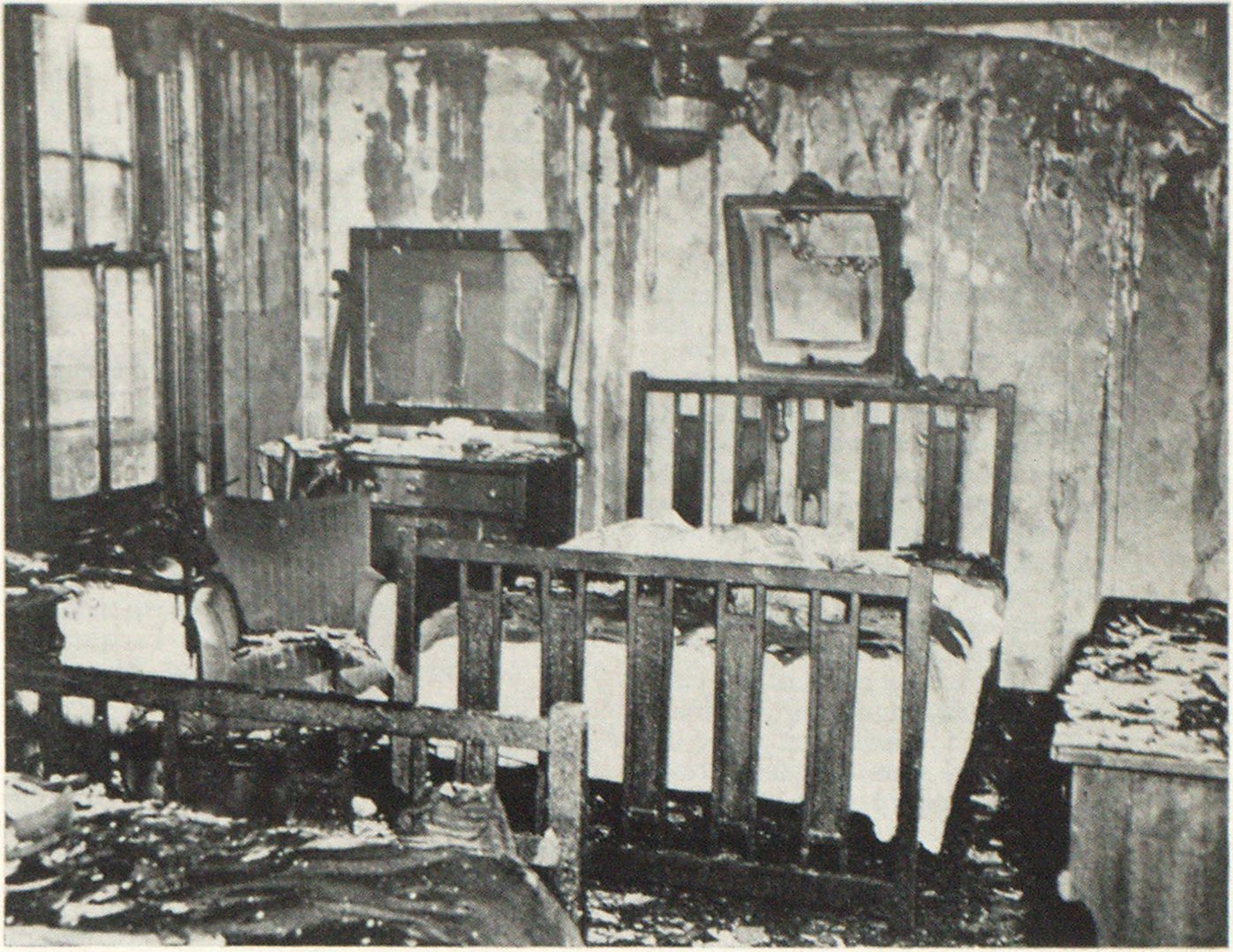

The interior finish of the guest rooms in general consisted of papered walls and painted ceilings (it is reported that some rooms had up to five thicknesses of wall paper). The floors were covered with carpet on felt padding. The larger portion of the windows were provided with cloth drapery and a number were also equipped with wooden slat venetian blinds. The furniture was of the customary wood type, most rooms having one or two upholstered pieces. Each room is said to have had radio and ceiling fan.

During the twelve months prior to the fire, extensive interior redecorating had been conducted throughout the hotel but this work is understood to have been completed about last October.

The hotel is not equipped with air conditioning or forced ventilating system, except for small portion of the mezzanine floor. The marquee on the Peachtree side is all-metal and, at the time of the fire, was fully covered over by a canvas canopy on metal stanchions. The space on the marquee was reported variously used for outdoor dining purposes.

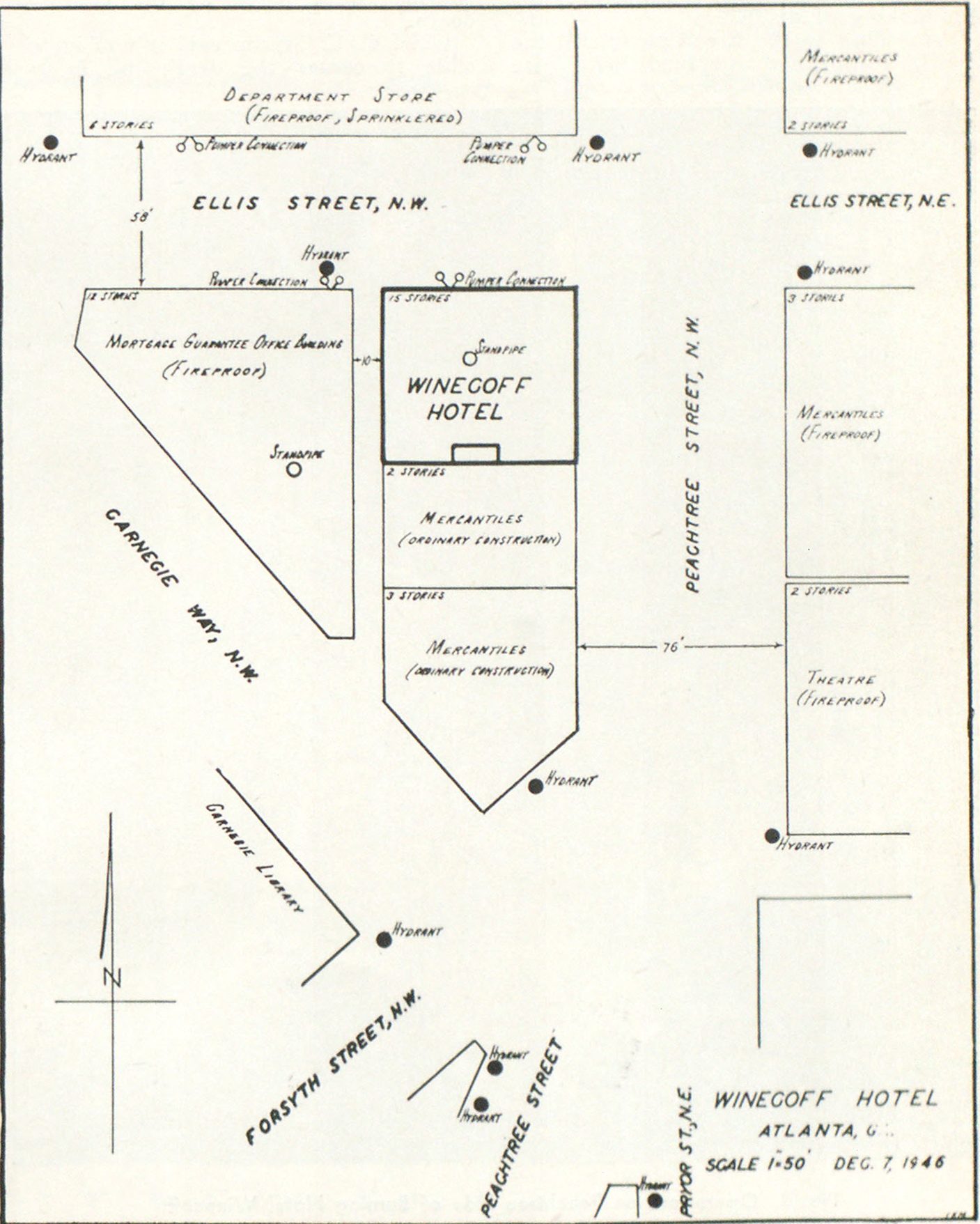

As is shown in the street diagram (see Fig. 4) there is a moderate-sized three story, fireproof mercantile building located seventy-six feet across the street to the east of the hotel. To the north, fifty-eight feet across Ellis street, is a large six-story sprinklered fireproof department store. Directly adjoining the hotel on the south is a two-story and three story brick, wood-joist mercantile building, separated from the hotel by a blank wall. The wall of the hotel above the roof of the south exposure is blank except for window openings in the small court section, which starts at the third floor and continues to the roof. These window openings are protected by wired glass in approved metal frames.

On the west, a twelve-story and basement, fireproof office building is located (Fig. 3) separated from the hotei by a 10-foot alley. Unprotected window openings in the west wall of the hotel face properly protected openings in the east wall of the west exposure; the roof of this building is about on the same level as the fourteenth floor of the hotel. This building played an important part in rescue and fire fighting operations.

As has been said, there were no outside or inside enclosed fire escapes, no service elevators or dumbwaiters. Room service was supplied by way of the passenger elevators.

At the time of the fire, the hotel is said to have had about 125 employees, a large number of them colored. There was no organized fire fighting staff and details on fire drills and training of the staff are lacking.

W. F. Winecoff, original owner of the building, operated the hotel until March, 1915, when it was leased to the Winecoff Hotel Company Inc., of which Robert P. Meyer was president. In the “30’s” the hotel was bought by the Hightower, interests of Thomaston, Ga., later was acquired by the Tennessee Realty Company and then by the King Investment and Security Company. In September, 1943, the hotel property was bought from King Investment and Security by Mrs. Annie Lee Irwin of Utoy road, SW., Atlanta, with the Meyer interests retaining the lease until 1945, when the lease was bought by A. F. Geele, Sr., A. F. Geele, Jr. and R. E. O’Connell. Mr. Winecoff, who died in the fire, had retained two rooms in the hotel.

Fire Believed to Have Started on Third Floor

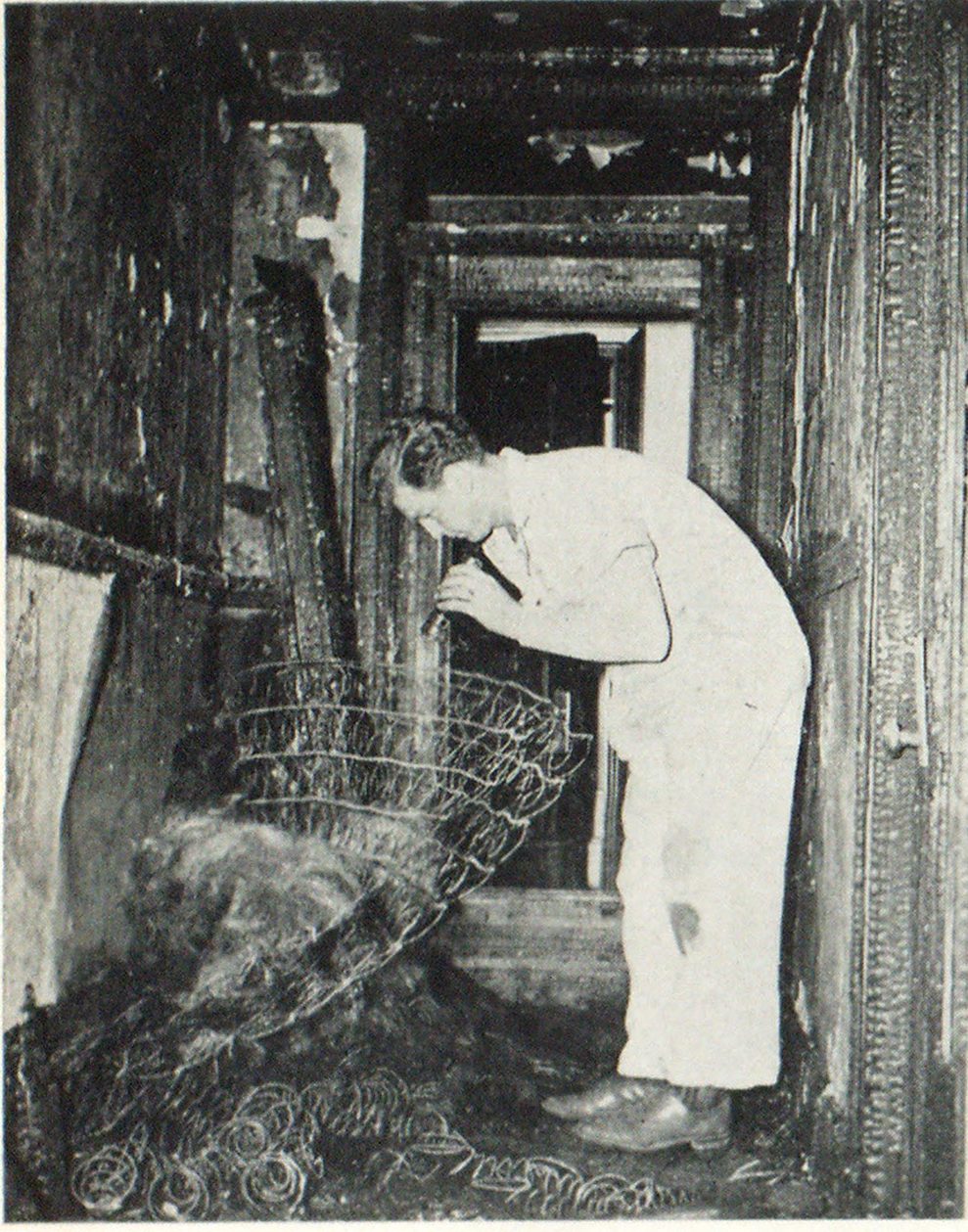

Although the specific cause of the fire is unknown at this writing, investigators have placed the point where it is believed to have started. From the nature of the burned area and the evidence indicating the direction of the spread of the fire in that area, investigators locate the point of origin on the third floor, in the hallway in the southwest portion of the building (see Fig. 7).

Here a partially burned mattress, believed part of a folding bed, was found. This was not far from Room 326. It is said the bedding had been removed from another third floor room, which was to be converted into an office, and witnesses place the bedding in the hallway prior to the fire. Two guests who occupied Room 326, and who escaped the flames, said when interviewed that they were asleep and could not say how the fire started.

Solicitor Gen. E. E. Andrews told reporters a preliminary examination by a State chemist showed the innerspring mattress, stored in a third floor hallway of the Winecoff, and believed to have been the origin of the fire, contained an inflammable oil, and that a preliminary report from officials of the U. S. Bureau of Standards showed the wainscoting in the Winecoff hallways was highly inflammable.

Confusion Over Discovery and Cause

Based on available reports at this writing investigators have revised their thinking into the cause of the fire to include the possibility of arson. They have as yet also, failed to solve the chronological puzzle of what time the fire actually started and what happened to the variously estimated 10 to 27 minutes that elapsed between when the blaze was first discovered and reported, and 3:42 A. M., at which time the fire department received its first notification (by telephone) of the fire.

Evidence presented by Solicitor E. E. Andrews to the Fulton County grand jury injects a note of mystery into the investigations. It discloses that a third floor guest reported hearing hasty footsteps outside his room shortly before the blaze.

A salesman reportedly testified that he heard a rattling of his doorknob, and investigated to find the corridor aflame. “Driven back into the room, he remained there until firemen had the blaze under control, then escaped . . . via the main stairway.”

His testimony was said to be the first indication there was any activity along the third floor corridor for a considerable time before the hotel’s elevator operator reported the fire shortly after 3:30 A.M.

The Solicitor also disclosed receipt of reports that two brothers, sharing a fifth floor room, earlier had invited a male guest to their room, engaged in a dispute with him and later forcibly ejected him. Hotel employees had been summoned, he said, to quiet the disturbance.

Several boys from Rome, Ga., attending the Youth Assembly, who were registered on the third floor, told of hearing loud shouts and curses from Room 330 for some time before the fire. When they heard someone from the room shout “Fire!”, they at first paid no attention but opened their door to discover the corridor in flames.

Further than this, a reported gambling party on the third floor received the attention of investigators, who also found another poser in attempting to find the answer to two false alarms reported to have been turned in from a box near the Winecoff earlier in the night.

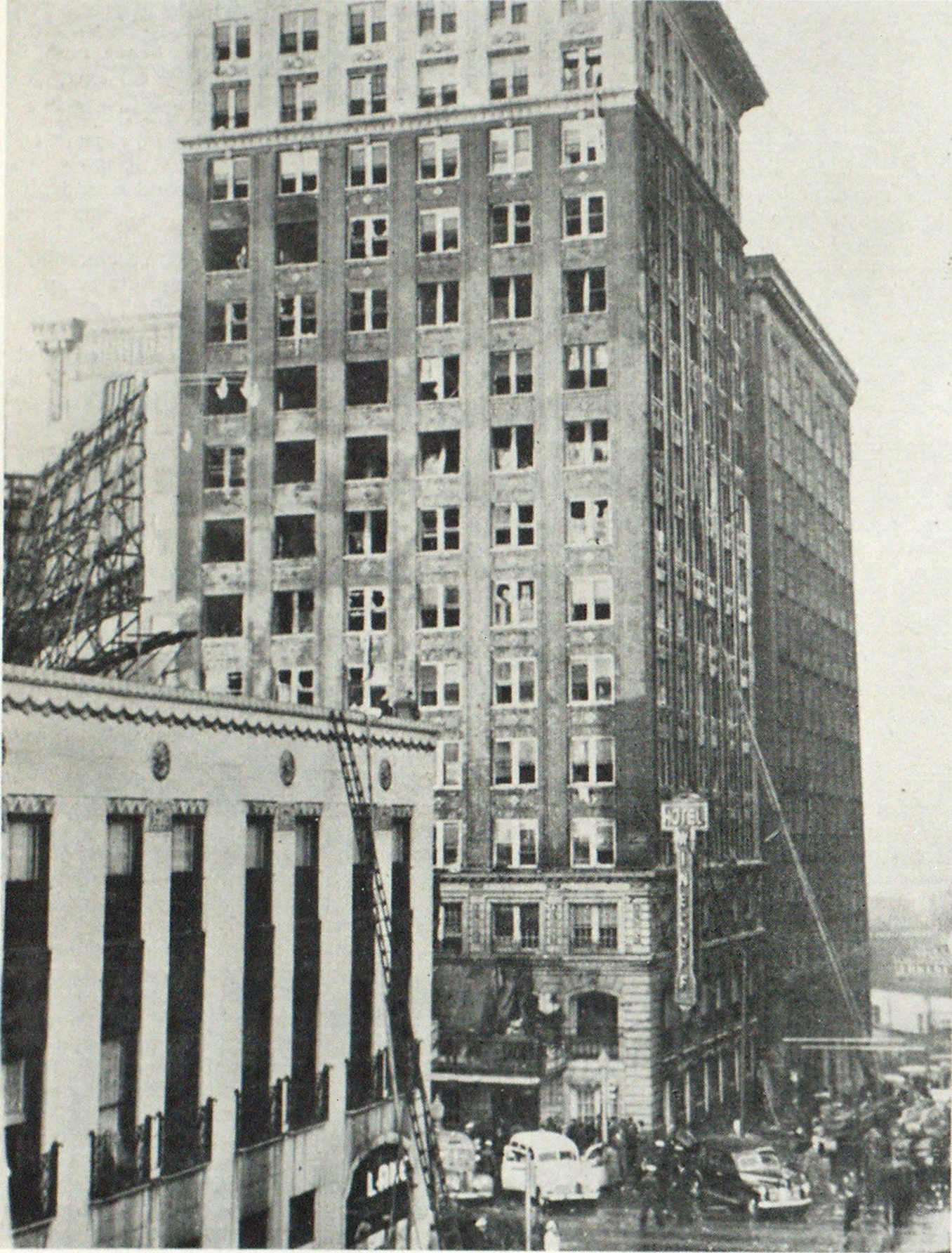

Fig. 3. Dawn Reveals Destruction at Winecoff Hotel Fire toward neartheast corner of the hotel on morning after the fire, while victims were still being removed. rear in twelve-srtory Mortgage Guarantee Building which played large part in rescue and fire fighting operations. A left foreground is three-story mercantile structure from which streams were also directed

Another avenue of investigation is the fact that a known Atlanta pyromaniac, who reportedly escaped from prison two months before the fire, is still at large. Reports, unconfirmed, called this ‘pyro’ a false alarm fiend and said he had touched off previous fires in hotels. He is being sought at this time.

This and other evidence doubtless accounts for the statement made by former New York Fire Chief John J. McCarthy, after his initial survey of conditions in Atlanta; “either one or two possibilities are tenable—incendiarism, or the fire was burning a long time before discovery. In my 32 years of firefighting experience I have never seen such devastating effects of fire from such a small point of origin.”

The puzzle of the missing time between discovery and alarm also has not been solved. The evidence indicates that on the morning of the fire, there were on duty in the hotel the night desk clerk, one bellman, the night building engineer, one female elevator operator, a night maid and a cleaning woman. Information is not available concerning their locations and actions prior to and following discovery of the fire, with one or two exceptions.

According to the night clerk, Comer Rowan, it was customary for the building engineer and a bellman to make the rounds of the hotel’s corridors about every two hours during quiet periods (no evidence has been released to indicate that they found any early morning disturbances in the hotel.)

Some time between 3:15 A.M. and 3:30 A.M. the bellman received a call for ice water and ginger ale from a room on the fifth floor (510). The building engineer, who was just starting to make a round of inspection, accompanied the bellman to the fifth floor and at the invitation of the guest, both entered the room.

A few minutes after the bellman and engineer had left the first floor, the elevator operator took some guests to about the tenth floor and upon the return trip to the first floor detected the odor of smoke. This she reported to the night clerk Comer Rowan, placing it, she thought, between the fourth and sixth floors.

Rowan states that he sent her right back up to find the bellman and the engineer to tell them to make a check and that he himself went out in the lobby to take a look. He adds that he went up on the mezzanine, and there he saw the reflection of the fire in the stairway above, after which he came back down and turned in the alarm. He places the time at about 3:40 A.M. Following this, he started calling the guests, beginning with Robert O’Connell the manager, in his room on the sixteenth floor. He then called Mr. Thatch the desk clerk and Miss McDuffie, the reservations clerk and then started to phone the guests’ rooms.

Rowan’s statement in this connection is that he told them the hotel had a fire and to please keep their doors closed so as not to make a draft and not to get excited because the firemen were already there. And he states that the firemen were in the lobby working up to the fire at the time he was operating the switchboard.

It is disclosed that the colored elevator operator, failing to locate the bellman and engineer, and becoming excited at the evidence of fire, returned her elevator to the basement. She then ran upstairs to the main floor shouting that the building was on fire. It is said she reported she saw the glare of flames through the wired glass doors of the elevator as she descended from the fifth floor; if this is true it would indicate the fire was already ascending the stairway.

Rapid Extension of Fire Mystifying

All available information supports the fact that the fire had gained considerable headway before discovery and that hallways from the third to the fifth floor were involved upon the arrival of the fire department.

Wonderment was expressed by some investigators over the speed with which the fire spread, considering the limited amount and type of combustible material it had to feed upon.

The report of the National Board of Fire Underwriters says: “Although the hallways contained a relatively small amount of combustible material, consisting of carpet, painted surfaces, wooden room doors and trim, fire was intense and spread rapidly due to natural draft created by the centrally located open stair shaft. All doors had transoms, with wood panels and a large portion of these transoms were open or partially open, thus permitting heated gases, smoke and flames to enter rooms “

Firemen reached the top, or fifteenth floor, about 6:30 A.M., by means of the interior stairway, progressively extinguishing or controlling the fire floor by floor as they ascended from the third floor. Their operations are detailed later on.

From the third floor, the fire damage to the hallways and rooms gradually increased up to and including the ninth floor and lessened from that point up to the fifteenth floor. On the top floor, unlike the usual fire which travels up a shaft and mushrooms laterally, the damage was limited to hallways and was small. The heaviest destruction was from the seventh to the twelfth floors, inclusive, it is reported.

From the evidence of the fire damage, and relating this to the behavior of fire and its extension, it is apparent that the stairways and hallways from the third floor upward were charged with smoke, flame and more than likely toxic gases, very shortly after the arrival of the fire department, if not before. Therefore, even on the upper floors, where least damage resulted, travel through the hallways was practically impossible. Some students who studied condition, are of the opinion that, even had there been outside fire escapes on the buildings, the impassible halls and corridors would have made them inaccessible except to those whose rooms opened or bordered on them.

Fig. 4. Map of Fire Area at Atlanta, Ga., Adapted from Diagram by N. B. F. U.

Heat Reaches High Intensity

Investigators were not only surprised at the rapid spread of the fire, but at its intensity in some sections of the hotel, considering the combustibles in those areas.

Evidence of extreme heat, reported in excess of 1500 deg. F. in some rooms, is found in the following: fused and melted electric light bulbs; melted down electric ceiling-fans; cracked porcelain bowls; twisted heavy metal doors on elevators; nothing but bedsprings left of some room furniture; melted-down telephones; complete consumption of wood doors and trim; tile walls exposed and some cracked; hotel fire hose totally consumed, only the metal fire nozzles and fittings remaining; spalling of walls and flaking of plaster.

According to the fire department, the floors completely involved with fire were the eighth, ninth, tenth, eleventh and twelfth. Little fire was encountered below the third floor, the damage being mostly confined to water and smoke.

As in the case of other hotel disasters, the fire appeared to play strange tricks, entering and burning out one room, to pass by the next, leaving it and its occupants scathless. Victims were killed in one room and spared in another almost across the hall, where heat and other fire conditions appeared about the same. There is a news account of one somewhat intoxicated man sleeping for over three hours through the entire ordeal without being affected while nearby, others succumbed.

Burns Caused Mosf Deaths

Eight days after the Winecoff Hotel fire, records in Atlanta’s Bureau of Vital Statistics, where 99 of the 119 death certificates have been recorded, show that 41 persons died of burns, 32 of suffocation and 26 from injuries received when they either jumped or fell from the 15-story building. However, condition of many of the bodies prevented authorities from determining whether the victims were burned to death or suffocated. In such cases “burns” were listed as the cause of death.

Chief C. C. Styron said it was impossible to center the death toll in any particular section of the hotel, as bodies were recovered on all but the second floor. Many fled from their rooms only to be trapped in other rooms when the fire spread. Chief Styron also said there was no way of ever determining what percentage of the persons who jumped could have ben rescued. The 26 deaths in this category, which also includes those who fell while climbing down improvised ropes of bedding, were listed under such injuries as “crushed body, multiple fractures,” or “crushed head and chest injuries,” or “crushed skull and multiple fractures of the body.”

Of the 41 fatalities listed from “burns”, most used but that one word as cause of death but other certificates elaborated to read “multiple burns of body” or “total body burns.”

Fire Department Operations

As is natural in disasters of this magnitude, where a city’s entire fire-fighting force must be hurriedly thrown into violent action, it is difficult to resolve operations into any comprehensive and chronological order.

That the Atlanta Fire Department faced an up-hill fight from the moment the first company units arrived at the scene is evident from all the available testimony. It was a situation calculated to bring dismay to the stoutest-hearted fire fighters.

The location of the start of the fire— whatever its cause—and its nearness to the unobstructed channel for the rapid and uninterrupted spread of smoke, heated gases and flames—the open stairway—was tragically ideal to (1) trap the greatest member of the hotel’s tenants above the fire yet in its path while (2) offering the department maximum hindrance to rapid rescue and fire control operations. In short, the fire at the very outset interposed a barrier which, at least for the first critical minutes of the disaster, limited life saving and extinguishment effectiveness. That the fire department extended itself to its utmost to overcome the handicaps is evidenced by the heavy toll taken of its officers and men during the action.

From reports made to FIRE ENGINEERING’S correspondent who worked at the fire and who later had opportunity to interview members of the first-due units, although no appreciable fire was showing on the exterior of the building when companies 1, 4 and 8 rolled in, there was ample evidence of the extent to which the structure was involved. The officers of No. 4 Company say that when they arrived in front of the hotel, one and one-half blocks from their station, there was no smoke or flame visible in the upper floors of the hotels, but as they were beginning operations people in the various rooms began to throw open windows and that this action was quickly followed by dense smoke. Most of these reports state that many persons were at windows when the first apparatus arrived and some indicate tenants were already jumping or falling from rooms.

Typical of the operations reports is that of Company No. 8, whose quarters are within about 800 feet of the hotel. This company, with a 1,000 gallon pumper and 100-foot aerial, is believed to have reached the fire within 30 seconds after leaving quarters. The lieutenant in charge of the pumper noted smoke coming out of the third and fourth floor windows. A hose line from this pumper, which was located at the corner of Peachtree and Ellis Streets, was laid up the stairs. At the mezzanine, or second floor, it was noted that the stairway above was filled with flames.

Fig. 5. Operations on Peachtree Side of Burning Hotel Winecoff Showing heavy concentration of apparatus with searchlights in operation. Life nets were employed near marquee shown in rear of trucks, but many persons were killed or injured in falls onto the marquee. Note lines carried over two-story mercantile building to south of hotel.

The officer in charge of the aerial ladder unit reported smoke coming out of windows on the third and fourth floors and that windows of practically all rooms were open, with people shouting and screaming for help. The aerial ladder was stationed on Ellis street opposite the center of the hotel and put into service for life saving purposes. The captain in charge stated that he rushed into the hotel and up to the third floor. Three women were found in the small court section on the south, who had jumped from the floor above and were still alive. Noting that the stairs to the floors above were a mass of flames he went back to the aerial truck and with another fireman took a 20-foot ladder to the Mortgage Guarantee Building (see Fig. 3). There this ladder and ladders from other companies were used as a rescue bridge across the 10-foot alley between this building and the hotel.

The captain of Company No. 1 reported that upon reaching the hotel he raised the aerial ladder up to people who were already in the windows on the Peachtree street side. Smoke was coming from numerous windows. This company swung their ladder from window to window, getting people off the ledges. Many persons were jumping and hitting the street. They rescued people with the 85-foot aerial, and could have saved more if the people had not jumped. They also rescued several people by having them jump into their life net. After rescue work on the outside was impossible, the men of this company set up a deluge set, playing a heavy stream of water into the top floors where rescue from the outside was out of the question.

Rescue Takes Precedence in Department Operations

Reports of the other companies responding on the initial alarm agreed as to the extent of the fire and the urgency of the rescue work, which was limited to exterior operations, with the ladders being shifted from window to window as rapidly as possible. The statements indicate that all firstdue engine companies took their lines through the lobby and up the stairs, trying to reach the base of the fire, which, by the time they had stretched, was roaring up the stairway and was ahead of the hoseline crews. It is said that men had to be removed from some hose lines to assist in rescue operations and that possibly this fact, leaving some hose lines undermanned, may have prevented more rapid advancement of those lines. However, the advancement of hose lines never stopped nor were they slowed down until the slack ran out, then hose was con nected to standpipes and the advance went on.

All accounts testify to the punishing nature of this effort. According to some the smoke was not so bad but the heat was terrific. It was in this early stage of the struggle that many of the firemen were overcome and had to be replaced by fresh crews. Among those who were so affected as to require hospitalization were Second Assistant Chief F. J. Bowen, who is reported to have sent in the second and additional alarms. Battalion Chief J. G. Webb, Second Battalion: Captains F. F. Anderson of Company No. 1 and E. L. White of Station 17. Chief Bowen, who was overcome by smoke and taken to Grady Hospital, said “I don’t knowhow many floors we went up. We went up so many because the fire was all around the elevators. Some other firemen and I were carrying a hose. Some of the men let go of it and the hose knocked me down the stairs.”

Fireman Knocked Off Ladder by Falling Body

A. J. Burnham, most critically injured of the eight more seriously injured firemen, was reported knocked from a 50-foot ladder, thirty feet to the pavement, by a body falling from above. He was attempting to rescue a woman victim who had fallen upon a cable on the Peachtree side of the hotel, and had worked her free of the cable, when a flying body tore him and his charge from the ladder. He suffered broken vertebrae and other injuries. Prior to his accident Burnham had brought three fire victims down the ladder and had _____ped hold a net for several more.

Out of the comusion, attendant upon the rescue operations, these additional facts are disclosed.

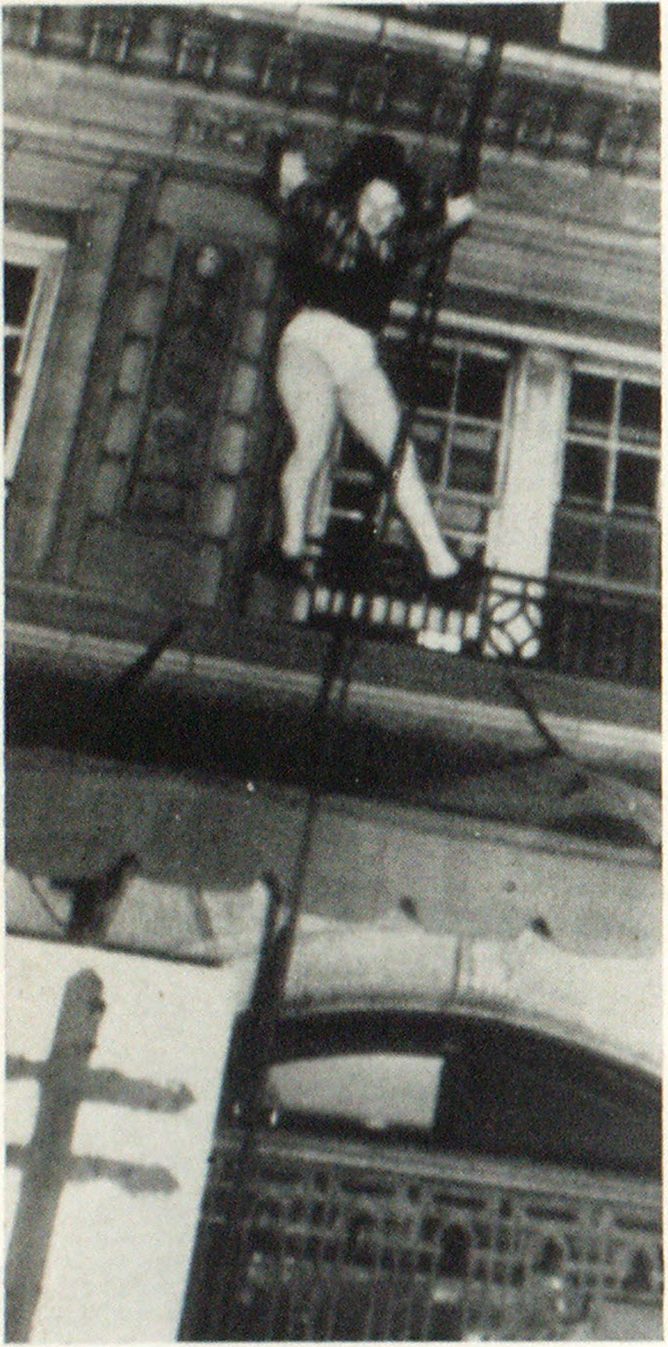

No. 1 aerial truck operated from Peachtree street side, taking people out of windows as high as the ladder, fully extended, would reach. Other persons succeeded in climbing down ropes made of bedclothes to gain foothold on the laddey. Still others fell in the attempts to employ such rescue means and endangered the men working on the ladder.

No. 5 aerial ladder, a 55-foot junior type, was operated from beneath that of No. 1, the men of this truck effecting several rescues.

No. 11 aerial (75-ft.); No. 8 (100-ft.), and No. 21 (65-ft.) performed rescues from the Ellis street side of the hotel.

Short ladders were used to bridge the alleyway between the Mortgage Guarantee Building and the hotel and many rescues were effected by this means, some of them of spectacular nature. Firemen crossed and re-crossed on the small ladders, leading grownups and/or carrying youngsters, then returning for more. Later they used the ladders to bring out the victims. These operations, our correspondent states, were exceedingly dangerous because of the attempt of persons on floors above trying to jump to the ladders. One body landed on a wooden ladder, breaking it in two and both the body and the ladder fell to the ground. This ladder was quickly replaced by an aluminum ladder, and this, in turn, was bent by a falling body.

Fig. 6. Floor Plan (Third Floor) Which Is Typical of All Floors Above Second. Fire Is Believed to Have Started at Point Marked X” I

Five members of one family escaped via knotted blankets and bedclothes, and fire department ladders, from the tenth floor. Lost in the smoky hallway, after attempting to find an escape from the floor, they finally stumbled into another room occupied by a young couple. Wet towels were used to breathe through and efforts made to attract the firemen from the windows. About the time hope was lost, firemen turned a spot light on them and they saw efforts at rescue being made at the ninth floor. The bed-covering rope was fastened to the radiator and one man managed to reach the top of the ladder by this means. A fireman brought up a rope to him and he tossed it to a brother in the tenth floor window. This in turn was tied to the radiator and the entire family in turn came down the line to the ladder, and safety.

Two doctors of Grady Hospital crawled across the bridge ladders into the upper stories of the hotel to examine and treat victims, making several trips in the smoke on slippery ladders. An Army major saved his family by means of an improvised bridge thrown across from the root of the Mortgage Guarantee Building into the hotel.

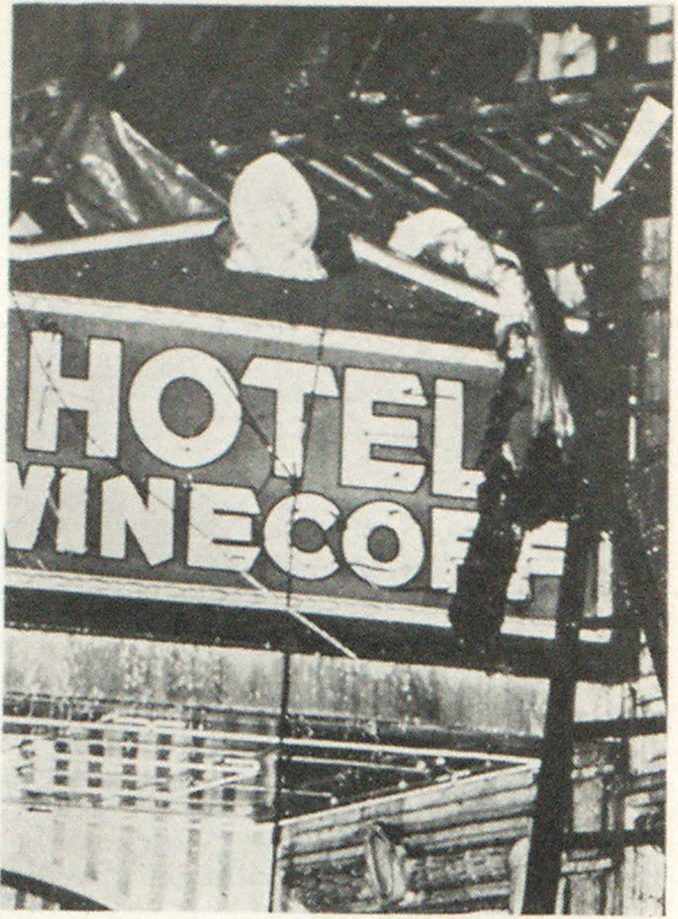

Meanwhile, firemen on the streets were dodging falling bodies, luggage and wearing apparel and even hotel furnishings, the latter in some instances thrown out to attract firemen’s attention to those marooned above. Falling bodies struck fire apparatus. A policeman and a volunteer worker were injured when a plunging victim struck them. Panic-striken women threw their children out of windows, then followed them, to death. In the front of the hotel, bodies crashed onto the marquee; some rebounded to the street, to narrowly miss firemen, and others were brought down from the marquee. One body struck the hotel’s neon sign, which remained lighted during the tragedy, rebounding from it to the street. Fire department ladders were struck and damaged by plummeting bodies.

Life Nets Employed

It is understood the department has several modern folding canvas life nets and all but one of these were used at the fire with varying success, due to the varying heights from which some persons were forced to jump. Ladder No. 4, which carries a net, was out of action, being in the shop. The department also has several of the old rope type nets, but it is reported these were not used.

Although accurate data are not available at this time, it is said that many persons were saved by nets when jumping from the lower floors. One net was used near the marquee and it is reported that some persons struck the overhang when they misjudged distances in the smoke and semi-darkness. A number of men were injured, both firemen, policemen and volunteers, none seriously, however, in efforts to hold these nets.

The department’s floodlight truck was employed to full advantage, lighting up the exterior of the building, both on the Peachtree and Flllis streets sides. It was also used to aid interior lighting.

Four streams were directed across Ellis street, from the top floor and roof of the department store, using its stand-pipes. These were credited with preventing death to a number of persons trapped on the fourteenth and top floors of the hotel, by knocking down the flames and heat. Testimony of survivors speaks of the beneficial effects of these streams. Several fire streams were operated into the hotel from the roof of the two-sto.ry mercantile building just south of the hotel.*

It is reported that several deluge sets and an additional Multiversal pipe were employed during the height of the fire, but operational details are not yet available.

Radio a Boon

Atlanta has equipped chiefs’ cars with two-way radio, operated on the police radio frequency, and this communication facility was employed to advantage throughout the fire and afterward. Multiple alarms? were all sent in by radio from departmental car? to fire alarm headquarters. By means of short-wave radio apparatus, no longer needed at the fire, was dispatched to various vacant fire stations with saving in time. One fire chief’s aide, reporting on the fire, advanced the belief that walkie-talkies would have been particularly useful in maintaining voice communications between working units and personnel.

*Although the extreme vertical range of ladder and street streams provided limited penetration, they were effective in cooling many rooms and furthering rescue operations. They also had a certain psychological value for trapped tenants.

Fig. 7. Where Fatal Winecoff Hotel Fire May Have Originated D. C. Reed, building engineer, examines remains of the folding bed in the third floor hallway, in which the fire is believed to have originated. Walls and trim show evidence of intense heat.

Fig. 8. How Fire Traveled by Unprotected Stairways This picture shows section of east corridor on seventh floor. A flight of unenclosed stairs is at left between the elevators, one of which may be seen at right of stairs.

Commercial radio was also employed in many ways, to bring medical aid, blood plasma, and volunteer workers; to help in identifying victims and locating missing persons. Appeals were broadcast by Chief Styron for outside aid and by Mayor Hartsfield and other officials for the help of emergency units.

Emergency Forces Mobilize

The city’s emergency disaster forces were quickly mobilized. By 4:00 A.M., the local chapter of the Red Cross had set up field stations and later installed twelve telephone trunk lines to handle inquiries concerning casualties and the missing. The canteen corps set up a unit in a nearby drugstore. Motor corps members transported relatives of the dead and injured to hospitals and morgues.

The Salvation Army sent its Southeastern Area headquarters personnel to Atlanta and aided in handling inquiries that poured into the hotel. The Boy Scouts mobilized units and rendered efficient aid.

The heaviest drain came upon the city’s hospital and medical services, notably Grady Hospital, which took care of most of the casualties. All available ambulances were pressed into service, some of the ambulances transporting injured averaging fourteen trips per hour to the hospitals.

The entire police department was called into action and closed off the fire area against the crowds of spectators that rapidly formed. Several policemen were injured performing rescue work and otherwise aiding firemen.

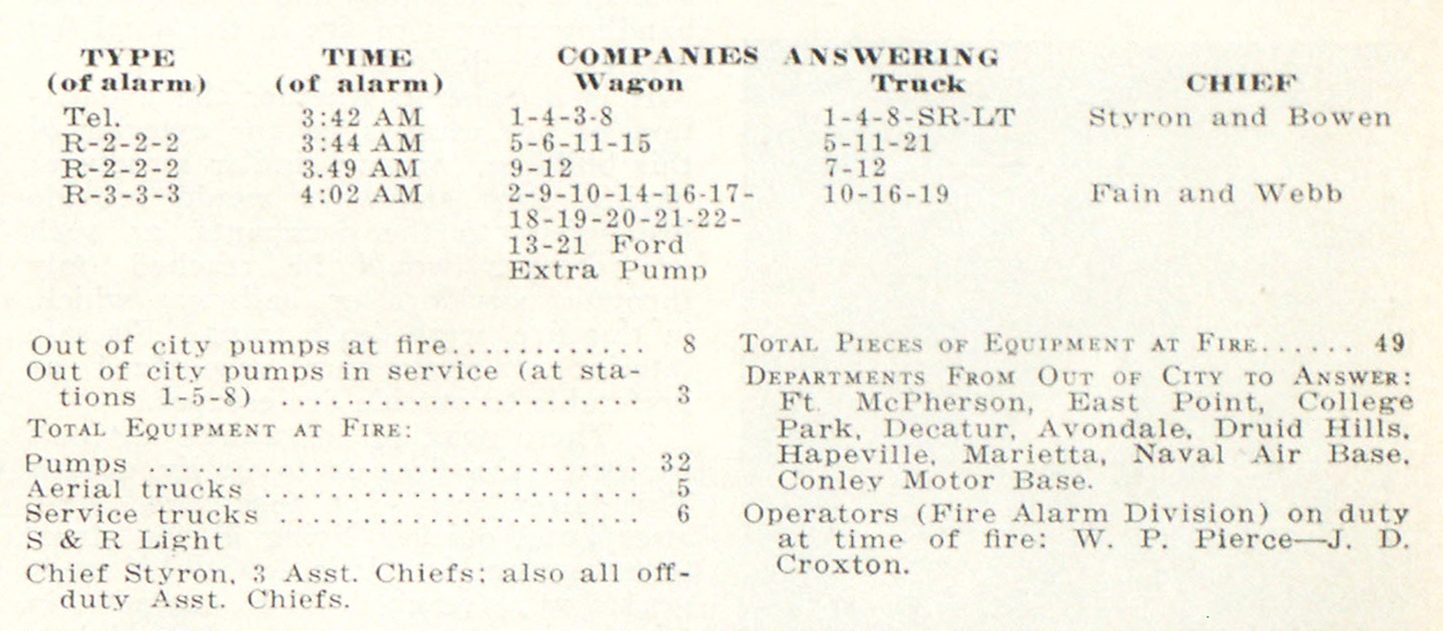

Fire Department Response

The fire department response was prompt and thorough. Although the initial alarm to fire headquarters was by telephone, a full box assignment was dispatched. This, as will be noted from the report of the Fire Alarm Division, W. L. Medlin, Superintendent, to FIRE ENGINEERING, which follows, preceded the second alarm by only two minutes. The speed with which the department got into action is indicated by the fact that within ten minutes from the time the first telephone call was received at the Fire Alarm Division, the city’s entire fire fighting force was at, or enroute to the fire, while out-of-town help was being summoned.

This rapid transmitting of the additional alarms by first-due officers attests the extent to which the fire had progressed in the hotel and the gravity of the situation faced by first arriving units.

A further interesting fact, in this connection, is that all the extra alarms were transmitted from the fire ground by radio, from the chiefs’ cars.

The following is from the report of the Fire Alarm Division, Superintendent Medlin, to FIRE ENGINEERING:

Fig. 9. Damage in a Typical Bedroom of Ill-Fated Hotel One of the bedrooms after the fire. Although, unlike other rooms these furnishings were not consumed by flames, there is evidence of intense heat. Note ceiling fan, overstuffed chair and mirrors (unbroken)

Department Units Close By

Number 4 Engine and Ladder are located 1 1/2 blocks from the hotel; Number 8 Engine and Ladder (100 Ft. aerial) 2 blocks distance; No. 1 Engine and Ladder (85 Ft. aerial) approximately 1/2 mile distance and No. 3 Engine Company also approximately 1/2 mile distance.

Conclusions

Based on available evidence, these conclusions may be drawn from the Hotel Wincoff holocaust:

- The major contributing cause of the tragedy was the open, unprotected stairway leading from third to top floor and which was a perfect channel for providing draft, and extension of flame, heat and gases. Contributing to tin-rapid extension doubtless were the fully or partially opened transoms and doors (as tenants attempted to flee rooms) and the opened windows.

- Another feature of the hotel’s construction which played its unfortunate part was the wood doors and plywood transoms, the wood trim and the heavy carpeting. The combustible, paintedover burlap siding, or dado, in halls was a hazard.

- Even though a building may be of non-combustible construction, the contents, decorative material and furnishings may produce a fire of serious magnitude and which will quickly fill the hallways and corridors with toxic gases of combustion.

- The majority of the deaths were attributed to suffocation. Toxic gases, such as were present, were the products of the combustion of the furnishings, particularly the wool and cloth carpeting and the painted, burlap siding, or dado. Early in the fire there was heavy smoke, followed by heat of considerable intensity. Firemen complained not so much of the smoke but this severe heat, which appeared to consume necessary oxygen in the stairway up which they struggled.

- Local building and fire prevention ordinances failed to cover conditions such as existed in the Winecoff Hotel, notwithstanding the lessons taught by the June LaSalle Hotel fire in Chicago, and the Terminal Hotel fire in Atlanta, of some years earlier. Even when the city inaugurated the necessary regulatory measures, they were soon discarded as too severe, and because it was claimed they could not be made retroactive.

- Storage of bedding and mattresses in hallways, as was done in the Winecoff, was an invitation to trouble and if, arson was the cause of the fire, as is claimed by some, it provided the arsonist a ready-made “torch”.

- There were no exterior fire escapes; no alarm system; no sprinklers and no organized watchmen’s service. Nor does there appear to have been any effort to organize a fire fighting crew or to train the hotel employees in fire prevention and fire control. The system of inspections and the method of handling reports of fire in the hotel left much to be desired.

- There was no organized attempt to locate the fire, or to notify guests. The latter were not telephoned until after hotel officials living in the structure were notified. It is doubtful if many guests were reached. The operator, in telephoning, appears to have used better technique than has heretofore been used under similar emergency conditions in that he did not urge guests to leave their rooms.

- The fire did not enter the elevator shafts (or any of the small pipe shafts) although elevator doors were buckled by heat. It would appear that this is proof that shafts can be isolated and protected against fire and its vertical extension.

- There appears to be a period of some time between the first discovery of the fire or evidence of it, and the notification of the fire department. This delay is variously estimated at from ten to twenty-seven minutes.

- Whether or not the hotel came within the definition of the term “fireproof” as established by the underwriters is debatable. In brief, the underwriters’ interpretation of a “fireproof” building is one which can be entirely burned out. without destroying or seyiously damaging the building itself. It is a fact, however, that people believe in the advertising of hotels and other dwelling places which labels them “fireproof”, whereas, as has been demonstrated time and again, the combustible furnishings and contents of the structures give the lie to this advertising. It would be in order to revise the standards under which owners or operators of all or any multiple dwellings are permitted to use the term “fireproof” (or even “fiye resistant” or “fire retarding.”)

- No criticism of the Atlanta Fire Department has been made either for the way in which it fought this fire or its inspections of the hotel prior to the fire, and its fire prevention division’s acceptance of the hazardous conditions in the hotel. It would appear that in the latter respect, as in the case of so many similar fatal fires, the fire department’s hands were tied through inability to enforce recommendations to correct conditions which its officials knew were hazardous.

- A factor which invariably contributes to fatalities in fires in places of public residence or assembly is that of panic. This stems from a number of causes, most of them familiar to experienced firemen everywhere. The hysteria which results in panic and the suicidal jumping from windows can not be overcome until the hotel interests of the country institute safety measures recommended by the National Board of Fire Underwriters, the International Association of Fire Chiefs, and other qualified organizations. There may always be panic attendant upon any fire in even the safest structure, but wholesale panic can only be controlled by preventing the fire or other emergencies which are the contributory causes.

- It would seem that now that the hotel industry has recognized the seriousness of the situation facing it, as evidenced by the employment of capable advisory counsel on fire safety measures, it would be in order for the fire service and the hotel interests generally to get together for the study and discussion of the best remedial and corrective measures that can be taken, with fairness to all concerned.

Fig. 10. Split Second Before One Guest Met Death on Hotel Marquee One of the several victims who plunged to the marquee on the Peachtree side of Hotel Winecoff in early morning fire of December 7. This picture, made by an amateur photographer, is considered one of the most striking fire photographs ever snapped.

Fig. II. Where Fireman Was Injured During Rescue Operation on Hotel Marquee Close-up of part of Winecoff Hotel marquee showing part of ladder said to be that from which fireman was knocked by falling body, while trying to remove victim caught on overhead wires.