By ANTHONY KASTROS

The incident command system (ICS) is an outstanding tool that is nationally recognized and mandated for commanding incidents. Since the ICS was borne out of necessity in the 1970s from large-scale wildland fires, one of the stigmas is that it is only good for large-scale incidents. As I write this, my home is surrounded by smoke from the Soberanes Fire that has been burning here on the coast of central California for three weeks.

California’s Soberanes Fire (photo 1) consumed 132,127 acres of land, destroyed 57 homes and 11 outbuildings, and tragically killed one bulldozer operator. The fire was assigned the following resources: 291 engines, 99 hand crews, 21 helicopters, six air tankers, 60 bulldozers, 54 water tenders, and more than 5,000 personnel.

The ICS was needed to manage this immense, 11-week-long incident. However, the use of ICS for structure fires is still a bit of a challenge for some. The fire service’s instructor cadre has taught thousands of officers around America for nearly 24 years. The common theme with those who struggle with ICS is a lack of proper training. These smart, thoughtful, experienced, genuinely concerned firefighters were never taught how to effectively apply ICS to structure fires.

|

| (1) The Soberanes Fire on its second day. (Photos by author.) |

Most ICS training is relegated to defining the difference among groups, divisions, and branches. Even then, many officers struggle. Applying a tool at an actual emergency scene requires vastly more training than just reciting definitions. What if combat challenge contestants just watched videos but never went out onto the course and trained? What if engineers just read books about pumping and hydraulics but never touched a pump panel? What if we just read articles about stretching hose, cutting holes, and doing vent-enter-search but never had a hands-on drill? Get the point?

Suppose you walk up to an intelligent, experienced lumberjack around the dawn of the gas-powered, motorized chain saw. He spent many years successfully cutting down trees with a hand saw and an ax. He had heard of chain saws, but he never really used one; he thought they were full of problems and too complicated to use. So, he stuck with his trusty saw and ax.

Then, along comes some authority who says he has to use the chain saw (or that it’s a great tool). He scoffs at it. The chain saw is left in its box with instructions, a can of fuel, two-cycle oil, and bar oil. He thinks it’s too complicated, and he is just too busy to stop what he is doing long enough to read the instructions, let alone practice on it. What would be his motivation to use the chain saw, especially if the only time he tried it, it didn’t work?

|

| (2) The initial arrival view of a townhouse fire from the command post. |

Maybe the chain saw didn’t work because no one showed him how to properly use it in realistic conditions – or no one he felt was experienced anyway. He put the fuel in the bar oil reservoir, poured bar oil over the bar, and chopped at the tree with the chain saw like an ax. It would take him about 10 seconds to realize, as he suspected, that this overcomplicated tool has no use in the real world. He would go back to his ax and hand saw with even more confidence and verve with the belief that these were the better tools all along.

That’s exactly what has happened to ICS in some people’s minds regarding structure fires. As mentioned above, no one argues the benefits of ICS on large-scale incidents. One of the problems with training is the failure to recognize the critical differences between wildland fires and structure fires, and that applying ICS in a wildland method to a structure fire is doomed to fail.

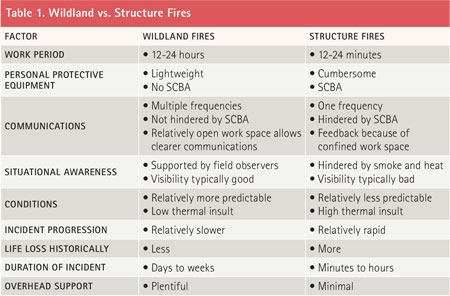

Table 1 shows some fundamental differences between wildland and structure fires that are of particular importance to an incident commander (IC).

|

| Table 1. The most critical factor overlooked for this issue is that wildland fires have little to no need for interior structural firefighting. For this reason, structure fires have very different complexities than wildland fires in which structure protection is performed. Interior structural firefighting and exterior structure protection on wildland fires are two completely different animals. |

We must recognize and respect house fires for what they are: the fires that claim the greatest loss of civilian and firefighter lives every year. According to the U.S. Fire Administration, residential fires were the leading property type in fire deaths (76.5 percent), fire injuries (78 percent), and dollars lost (55 percent) in 2013; this includes exterior wildland fires. We call house fires “bread and butter,” but this name represents a lack of respect for our greatest enemy. So, how do we apply ICS to structure fires (yes, even house fires) with more effectiveness?

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) 5

We first must acknowledge that structure fires commonly feature some or all of the top 5 NIOSH operational factors in line-of-duty deaths (LODDs). A lack or improper amount of the following factors also contributes to civilian injury and loss of life: risk assessment, incident command, communications, accountability, and standard operating guidelines (or a failure to follow them).

But don’t take NIOSH’s word for it; look at your previous fire that went bad or where operations were sloppy. Chances are, one or all of the NIOSH 5 were present. The question then becomes, “How does ICS fix these factors?” Let’s look at each one.

Risk Assessment

Improper risk assessment is routinely cited in LODD reports and blue or green sheets and can be easily attributed to missed victims, injuries, dysfunctional operations, and so on. Most likely, there was a lack of appropriate situational awareness, knowledge of the building, knowledge of the fire location, fire size, and so on. How many reports have you read where the first-arriving companies “didn’t know”? Missing or unknown basements, cocklofts, second floors, fire locations, and more are not a result of firefighters lacking knowledge; they are a result of firefighters focusing on tasks while the IC focused on strategy. The result is a “tactical gap” where all the aforementioned items reside.

|

| (3) Within 2½ minutes of arrival, this fire began to escalate. Division A was assigned and responsible for all interior crews and the objectives of fire attack and search. The supervisor knew where crews were in the building at all times. |

As an IC, it is extremely common for me not to see the building from the incident command post (ICP). When I do, it’s only one or two sides of a seven-sided problem (top, bottom, four sides, and inside) that is changing rapidly. Meanwhile, my crews are inside a burning building with zero visibility and auditory exclusion, and their adrenaline is pumping. They will not see all there is to see and process everything at the task level (photo 2).

The division or group supervisor resides at the threshold between the task level inside the building (companies working) and the strategic level outside the building (the IC at the ICP). From this vantage point, a division supervisor can see changes in smoke and fire conditions, read the building, assess victim profile, canvass and poll bystanders for victim information, anticipate the needs of the crews inside and account for them, and rotate crews as necessary.

Incident Command

The IC must set up a system that is sophisticated enough to handle current, future, and potentially unforeseen conditions that arise. One key is to not overbuild a complex system that is confusing or too top-heavy. This is a common error by those who apply wildland ICS to structure fires. Training is critical in successfully developing and applying your ICS rapidly to a structure.

For example, having an operations or planning section chief is considered “overkill” on a house fire. If an operations section chief takes over the fire entirely from the IC, the common question is, “What then is the IC doing?” Probably not much. Rather, it is much more effective to consolidate those resources under one boss and set up a division supervisor to supervise the crews inside the house, who then watches over crews, accounts for them, and communicates with them directly face-to-face instead of on the radio. This may not be possible on a wildland fire, but the close quarters of a house fire typically allow a division supervisor to account for and supervise the crews inside. This then allows the IC to consider other issues such as medical, roof operations, additional resources, exposures, staging, support of the responsible party, and so on. Some ICs are even saddled with public information officer and station coverage issues. How can anyone command a fire if he is worrying about coverage of the city at the same time?

Although an operations section chief may be overkill on a house fire, assigning a division supervisor for the interior crews, a division supervisor for roof operations (if warranted), and a group supervisor for medical can easily clean up your incident. For instance, the Division A supervisor at the tactical level would be responsible for the objectives of fire attack, search, door control, two-out line/rapid intervention crew (RIC), salvage, overhaul, accountability, and interior crew safety. He would refer to the crews working at the task level as their company identifier (i.e., Engine 1, Truck 2, and so on). For example, the division supervisor would be referred to as “Division Alpha” (photo 3).

|

| (4) This fire was in a three-story center hall apartment building. Division supervisors were on the second and third floors. |

In my department’s system, we dispatch nine resources to a house fire where four-person truck companies often split into two-person teams. This creates the potential for a 10:1 span of control for the IC. By setting up a Division A, a roof division, and a medical group, the span of control goes down to 3:1; this means one-third the radio traffic as well! As the incident complexity goes up, so should the ICS complexity. Although this is nice in theory, what does it mean for structure fires? The formula we teach is Building + Conditions + Resources = ICS. If any one of these three factors changes, so will the ICS. So, consider the building size, construction, layout, use, occupancy load, and other factors in your ICS. Also consider building size, location and extension of fire, number of victims, weather, and exposures.

Resources are different throughout the United States. Always consider the numbers and types of companies, staffing levels, greater alarm resources, overhead support, specialty units, and volunteer vs. career members. For example, although one division supervisor may supervise crews inside a 2,000-square-foot home, this will probably not be sufficient for a multistory building, a large commercial or apartment building, or a tenement with multiple victims trapped.

Templating can help you here. Having a handful of ICS templates that you can apply quickly to the rapidly changing and escalating nature of structure fires is an excellent way to organize your incident swiftly.

|

| (5) The Division 3 supervisor at the same fire communicates face-to-face with a company officer in the stairwell. Notice the division supervisor is wearing full personal protective equipment and SCBA so he can enter the immediately dangerous to life or health environment for accountability or communication. |

One of the axioms of ICS is that it is “incident driven.” This is true, but structure fires move way too fast to be reactionary (like a wildland incident). Wildland incidents tend to move slowly, so being reactionary is more tolerable. Structure fires are a bit more predictable, but they move much more rapidly. Whether through experience or preplanning, we set up our standard operating guidelines (SOGs) based on years of experience in building fires. ICS should have an SOG that allows for rapidly deployed preset templates that are adjustable to the incident.

Build these SOGs and adjustments around the three ICS inputs: building, conditions, and resources. Chances are that one of these inputs is the overriding factor that will drive the ICS more than the others.

For example, a multifloor center hall apartment building with fire on the second of three floors would probably warrant a Division 2, a Division 3, and possibly a roof division for the structure itself. Other tactical components would be a medical group and possibly a RIC, so these two crews would be warranted. The division supervisor for each floor would reside in the stairwell at the point of entry, accounting for crews and communicating with them face-to-face (photos 4, 5).

|

| (7) The Division A supervisor is seen on the right. He is moving around the structure, coordinating vertical ventilation with his crews inside, orbiting and entering the structure when necessary to account for and communicate with crews face-to-face. |

A similarly sized fire in a different type of apartment building may warrant a different ICS. An example would be a fire in a two-story garden-style apartment with occupancies that open to the outside through an external wraparound balcony. If the fire is on the second floor of a three-story building and the fire is now in the back of the building, a Division C supervisor could manage all resources on the second and third floors since he can see the crews going in and out. This is not the case in the center hall, where there are enclosed halls and stairwells.

Consider the same apartment fire in that same building with the same amount of resources, but add three trapped victims (a change of conditions). A “known rescue” template may be warranted in this scenario because the conditions of the three confirmed victims are now the overriding factor. You may establish a rescue group supervisor whose sole objective is to rescue the victims using whatever tactics and resources are necessary. If he needs an additional truck to support VES, then he would call the IC. Conversely, the fire attack supervisor would be solely focused on confining and controlling the fire wherever it is extending (photo 6).

This template would not work for the above center hall apartment building because the layout precludes one supervisor who is able to see and manage one of the functions described here. I have had known victims trapped in garden-style and center hall apartments, and I have used each of the templates described above. The difference was the building.

The point is that structure fires move too rapidly to wait and be reactionary with your ICS. A quick size-up should include consideration of your ICS so companies can be proactively deployed, accounted for, and supported while keeping radio communications to a minimum.

Communications

Communications are the most common challenge cited at tailboard after-action discussions. Self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), apparatus noise, saws revving, tunnel vision, auditory exclusion, and a host of other issues arise. In addition, structure fires usually begin on one frequency, causing a potential bottleneck of resources and radio traffic. A few years ago, my department had a firefighter fall through a roof while working at a commercial fire. The captain was unable to call a Mayday because of the volume of unnecessary radio traffic.

When the traffic does get through, transmissions by crews inside the building are often muffled and inaudible. I recently listened to a fire at which crews were operating inside a commercial building. No divisions were established, so everyone was talking to command on one frequency. The captain on the initial attack line called command twice with a CAN (Conditions, Actions, Needs) report. After the second failed attempt to understand the transmission, the IC stated, “I can’t understand you, but at least you are talking and alive, and that’s good enough for now.”

|

| (6) This garden-style apartment fire was supervised by the rescue group supervisor and fire attack group supervisor (seen at the bottom right), calling for more line from the engineer. He promptly returned to the rear to maintain contact with his crews. Both supervisors were company officers since the second battalion chief to the fire was delayed. |

When you establish a division, one of the first priorities of the division supervisor is to get in contact with his companies. This may require going into the building and getting face-to-face with the officers, which is the best option. Tell the companies, “You are now working for me. I am Division A. Do not talk to the IC anymore. I will be at the doorway or close by.” This immediately reduces radio traffic and leaves room for the unforeseen Mayday, trapped victim, or emergency traffic. If necessary, you can use the tactical frequency, but the vast majority of communication is face-to-face between the division supervisor and his company officers.

When using face-to-face communication, the need to communicate also is reduced because the companies inside the building now know that their boss is just outside the door, not down the street at the ICP. The need to relay information is reduced because the division supervisor is constantly reconnoitering the area and situation. The IC asks fewer questions, and the companies do less talking, yet the work gets done more safely, effectively, and efficiently.

My last structure fire was a townhouse building on a 110°F day at approximately 1230 hours. The building was comprised of two townhouses with a common attic, and fire had total control of the attic space over one occupancy. A light wind was also a factor. Our primary objectives were to search, prevent lateral extension, and extinguish. Because of the volume of fire, the ambient heat, and exposures, I called a second alarm. Even if we quickly extinguished, the overhaul and rotation of crews in the 110°F heat warranted a second alarm.

|

| (8) The second battalion chief, seen on the right (holding his helmet), arrives and replaces the company officer, who was Division A. This allows the company officer to return to his crew. The second battalion chief could assume another division role or be the RIC group supervisor if the fire warranted it. The captain on the roof is the roof division supervisor. |

The second-arriving company officer assumed command from the first officer, who was at the task level, initiating fire attack. He had command for about three minutes until I arrived. On arrival, I assumed command and assigned him Division A with Engine 109, Engine 108 (E108, his crew), Truck 109, Truck 23, and Engine 23 working for him. I stated on the radio, “All units inside the structure, Engine 108 captain is now Division Alpha. All units inside the structure – Engine 109, Engine 108, Truck 109, Truck 23, and Engine 23 – you are now working for Division Alpha, who is E108 captain.”

Approximately 10 minutes later, the second battalion chief arrived and assumed Division A from the E108 captain. This allowed the E108 captain to return to the task level with his crew (photos 7, 8).

The radio traffic immediately went to near zero. Crews now knew that their boss had accounted for them, and they communicated with him face-to-face. We now had room in our communications for rapid expansion or a Mayday.

Accountability

Every fireground firefighter must be able to answer the following two questions: (1) Who is your boss? and (2) what is your job? Unfortunately, these questions are often met with a look of confusion. Duplicate bosses and jobs are common, and this adds to the confusion. Over the past 20 years, command boards, T-cards (a tool from the wildland arena), and other tools have saturated the market. Although these tools provide accountability and can organize the incident, you must maintain another layer to achieve true, real-time accountability.

Again, one of the most critical jobs of the division/group supervisor is accountability. The supervisor has eyes-on, hands-on active accountability wherein the real-time location and function of companies and individuals are maintained constantly. A supervisor must know where the companies are in his division, what they are doing, how long they have been there, their point of entry/exit, and so on. This real-time active accountability is much more accurate and timely than the best of command boards.

|

| (9) This fire involved two homes. As division supervisor, it was imperative to keep moving between the two homes, accounting for crews and watching for potential threats. |

I have worked on multialarm fires in which T-cards were used at the ICP. Some companies assigned to the incident on the T-card board were released and returned to quarters; they weren’t even on the fire anymore! This is another example of using a wildland ICS tool on a rapidly moving structure fire with potentially disastrous results.

Recently, I was assigned Division A on an incident with two homes well involved. My objective was fire attack, search, and ventilation of both homes. All crews reported to me. The temperature was approximately 105°F at 1430 hours; there were some winds. My being assigned to Division A allowed the IC to handle medical, property owner support, and the calling of additional companies because of the extent of the incident. I tracked companies with a grease pencil on a burned-out boat in the driveway (photos 9, 10).

SOGs

The final factor in the NIOSH 5 is the failure to have or follow SOGs. A division/group supervisor can ensure that SOGs are being followed, no freelancing is occurring, and SOG adjustments are warranted. These issues can often elude the IC from the ICP, as the location is unifocal and distant.

|

| (10) Although not ideal, crews were tracked using active accountability with the help of a boat in the front yard. Usually, a legal-sized grease board works better, but a door, a car, a wall, or whatever you have can work in a pinch. The key was active, ongoing accountability. |

The ICS is an excellent tool that arose from the ashes of large-scale fires that claimed hundreds of homes in the 1970s. It has proven worthy and flexible to manage countless types of all-risk incidents. The effective use of ICS for structure fires requires rethinking the system with the unique characteristics of these fires in mind. You must consider factors such as time, communications, conditions, situational awareness, incident progression, life-loss potential, and overhead support because they vary greatly between wildland and structure fires.

Rapidly deploying preplanned ICS templates for your most common structure fires and scenarios will allow quick, proactive organization; accountability; and clearer communications from the start. This technique will also prevent the NIOSH 5 from coming into alignment as well as make for more safe, effective, and efficient operations. Like so many components of our job, practical application of ICS for structure fires requires training that is realistic, hands-on, ongoing, and supported by sound SOGs.

ANTHONY KASTROS is a 29-year veteran of and a battalion chief for Sacramento (CA) Metro Fire. He is founder of TrainFirefighters.com and TrainFirstResponders.com, teaching fireground command, tactics, leadership, and officer development throughout the United States. He was the FDIC 2013 keynote speaker and has published Mastering the Fire Service Assessment Center and the DVD series Mastering Fireground Command, Calm the Chaos, and Mastering Unified Command – from Hometown to Homeland (all published by Pennwell).

Command on Display: Notes and ICS

Applying ICS to All Departments–Big & Small

NIMS vs Agency Command

Fire Engineering Archives