By Alan Berkowsky and Edward Mohn

“Active Threat/Rescue Task Force” were newer terms just four or five years ago. When they were first introduced, there was significant push back not only from some in the fire service but law enforcement as well. As with any new concept, the key is to train and understand the strategies behind the suggested tactics. More importantly, with this type of paradigm shift, there had to be a “buy-in” from the bosses to support the concept both from a procedural standpoint as well as the financial aspect of new equipment and training.

Both fire and police have come a long way since the inception of the Rescue Task Force (RTF) concept. What has changed is lessons learned from the various active shooter incidents that continue to unfold in the most unexpected locations, times, and events. As part of the Illinois Tactical Officers Association’s (ITOA) Active Threat Curriculum, a class was developed titled, “Rescue Task Force: Command & Control.” With the wave of recent incidents, this class is constantly being updated.

The most significant change to the course in the last four years has been the course title. It is no longer “Rescue Task Force: Command & Control.” It is now, “Active Threat: Command & Control.” The reality, based upon numerous events and lessons learned, is that while RTF has a purpose and is a strategy that can be employed, it is just one strategy for reaching, treating, and removing victims during an active threat situation.

The original RTF concept and training program was the catalyst to this change. It provided us with a focus on how to train firefighters and police to work together in the “warm zone.” Historically, most fire and police departments have had good working relationships, but we typically worked in a parallel universe when on the scene of an emergency. For a structure fire, police would provide a perimeter for us to work and firefighters would perform fire suppression. We would work near each other, but traditionally stayed within our own zones.

RELATED

EMS Response to the Active Shooter

Active Shooter Response: Rescue in the Warm Zone

Active-Shooter Incidents: Planning Your Response

RTF created a process and a system in which firefighters and police officers needed to operate together as a single team. We needed to understand each other’s operational concepts and practices and take advantage of each other’s strengths. The RTF Command and Control Course demonstrates the importance of the unified command process to the chiefs, battalion chiefs, commanders, and supervisors from both disciplines. Fire and especially law enforcement must realize that when operational and strategic decisions are made collaboratively, it allows for the most efficient and effective use of resources with the end goal be to save as many lives as possible, a quickly as possible.

What Has Changed with Firefighters/Paramedics?

When we first started teaching the Basic RTF & RTF Command and Control classes, we heard comments from firefighters such as:

- It is not my job to go into a building that has not been secured and/or where an active threat might still be.

- We don’t have any equipment to protect ourselves.

- I didn’t sign up for this.

These were similar to some of the comments we heard from law enforcement decades ago when we first started teaching rapid deployment after Columbine (“That’s SWAT’s job.”)

Most of these comments were due to inaccurate information about the evolving RTF concept, with little or no exposure to actual training. What has changed? Once firefighters received the training, equipment, and had their concerns addressed, there was a significant increase in their comfort level and in their realization that one of these events could occur on their watch and that they needed to be ready. As with any skill set, once a person gets trained and is comfortable with the skill, there is “buy-in” and a renewed understanding of why this is now part of their world.

Whether the firefighter “buys-in” to this critical training or not, they will be dispatched to the active shooter incident and may be inundated with serious gunshot victims both inside and outside of the venue. There is no reason to place personnel in a situation like this without the needed training and expectations. An active shooter knows no socioeconomic, religious, ethnic or nationality boundaries. These attacks happen while at work, school and play—all present vulnerable targets.

What Has Changed with Law Enforcement?

The RTF concept was another operational change to what most police officers recognize as the ever-evolving active threat response matrix of tactics and techniques. When reviewing the historical changes that have occurred in law enforcement training and preparedness to active threat situations, you will recognize different approaches:

- Traditional response (pre-Columbine): Contain and wait for SWAT

- First generation response: Teams/formations, 4-5 officers including police rescue teams

- Second generation response: Solo entry/buddy teams/three-officer contact teams

- Third generation response: Multi-Assault Counter-Terrorist Action Capable (MACTAC)/urban tactics

- Fourth generation response: RTF, police and fire joint response in the warm zone

- Fifth generation response: (Covered in “What’s Next” below).

As with fire, the post-incident reviews and numerous incidents have caused law enforcement agencies to modify their tactics to address current world events and plan for the next attack against our citizens. Below are some of our observations after four years of training more than 900 police and fire chief officers/supervisors on RTF/active threat incident command and thousands of first responder RTF instructor and end user certification courses.

- Incident Command: When we first started

to teach the Command & Control Class, we would ask police bosses how many

of them had been on an active incident and stated over the radio that they were

command. Not a single hand would go up. When asked why, the response was, “We

don’t do that,” and that the hazing they would receive after the fact was not

worth the attempt. Four years later, when we ask the same question, about 25 percent

of police bosses raise their hand. Law enforcement is now realizing how

important incident command is both for control of the event and providing some level

of comfort to officers on the scene in knowing that someone is coordinating

their efforts. The following quote from

the Fire Department Blue Card Incident Command Program best describes why

having an incident command is so important:

- “If the first unit arrives to the scene and gives an initial radio report but doesn’t say they are assuming command, it screws up the event from the start. The most pressing problem for responders is no longer the incident problem; it’s who in command of the event. Managing and coordinating all the action that must take place. There should never be any doubt who the incident commander (IC) is or that there is an IC.”

- Working side-by-side with the fire department: This process took some time. When we first started the RTF instruction, it was difficult for the law enforcement teams to recognize their role was to protect fire so that firefighters could treat patients as quickly as possible. It was also important for officers to realize that they too needed to be knowledgeable in their ability to stop bleeding with pressure dressings and tourniquets. This applies not just to civilians but to law enforcement officers as well. They now recognize the importance of carrying a tourniquet and pressure dressings as part of their standard issued equipment at all times.

- Interoperability: Generally, most fire departments have conquered interoperability with the use of fireground channels. This is not the case for many law enforcement agencies, which are unable to share a radio channel with their neighboring departments who automatically respond on an active shooter event. It has gotten better, but much more work needs to be done in this area.

What Has Changed with the Response to an Active Threat?

- RTF: RTF is still a critical procedure to understand and practice. It provides a mean for police and fire to train together with a common objective. However, it is only one of several strategies to that can be used to access patients as quickly as possible. In reality, the RTF process may take time to set up and could delay treatment. RTF has been used in some of the recent events, but only after most of the patients have been moved and a second search was needed. Within the confines of incident command, police and fire bosses will need to quickly determine the best tactic to access, treat, and transport patients out of the Warm Zone to a triage, treatment, and transport area.

- Law enforcement-only RTF: This strategy was used in the Parkland Florida High School shooting since the status of the gunman was not immediately known and the school remained a hot zone. Police officers entered the school to bring patients out to the fire department for treatment. The law enforcement-only RTF and the incorporation of trained and equipped medics (TEMS) seems to be the most applicable emergency deployment tactic that can be quickly implemented and effectively used early on in active threat situations.

- The strategy: The most important decision to make, once the gunman has been neutralized or contained by the police, is how to access, treat, and transport the wounded as quickly as possible. Time is not on their side. They will bleed out quickly if we do not get to them and provide exsanguinating hemorrhage control.

These strategies include:

- Safe corridor/law enforcement stronghold: This method requires sufficient law enforcement officers on the scene to create a safe corridor (police protecting all access points, ingress and egress routes) for police and fire to pass through freely to treat and move patients to the triage area. This strategy is typically used in areas where there is a plethora of police officers who can quickly be assembled.

- Patient shuttle: The patient shuttle is used when the building is considered a Hot Zone due to the shooter’s location being unknown or if the shooter has access to windows and may be shooting at first responders. In this situation, vehicles are used to take patients away from the scene to a Cold Zone that contains the triage, treatment, and transport Area. This strategy was used in the San Bernardino shooting.

- Patient or casualty collection point (PCP or CCP): This concept is used when the building is so large that trying to take the patients out to the treatment area would not be efficient. A PCP is designated for the RTF Team to bring in their patients so that another team can move the patients to the treatment area. Again, this concept is labor intensive since multiple RTF Teams are needed to find the patients and then to move them from the PCP to the treatment area. In addition, an RTF will need to be assigned to the PCP to treat patients who are waiting to be moved. Incidentally, some PCPs will be already defined by the injured, as was illustrated in the Aurora (CO) theater shooting. There were three areas where injured patrons waited for help. Your first task as the fire incident command might be to assign a group to each pod of victims to triage, treat, and transport.

As stated earlier, RTF is a solid strategy but needs to be practice and assembled as quickly as possible to be effective.

RELATED

Preplanning Response to Active Shooter/Hostile Events: Proposed NFPA 3000

Reviewing NFPA 3000: Standard for Preparedness and Response to Active Shooter and/or Hostile Events

NFPA 3000: A First Step Down a Long and Perilous Path

As we continue to learn and experience what works and what does not, a few “keys to success” have been identified as solid Implementation strategies for an active shooter event. These include:

- Police must quickly notify fire that the shooter has been neutralized or contained so a warm zone can be defined and announced; the appropriate patient access strategies can be implemented and victims can be moved expeditiously. Delays have been noted when police fail to make these announcements and defined the warm zone and RTF rally point, resulting in the potential delay of accessing or treating patients.

- Law enforcement must get into the habit of participating in an incident command process with fire as soon as possible. When this does not happen, the mitigation of the incident becomes problematic and communications fails. It is important to reiterate that the unified command process and announcement of operational command brings cohesiveness, continuity of effort, and a certain level of comfort to officers and firefighters on scene knowing who is in command and who is coordinating their efforts.

- Implement the best patient movement strategy as quickly as possible to give every patient the best chance for survival. The reality of these situations is that we will not be able to save them all. But we can give them a better chance if we stop exsanguinating bleeding, provide on-scene advanced emergency medical care, and transport patients as quickly as possible to definitive medical care.

Train, train, train! These concepts only work when fire and police are familiar with them and have practiced them on a regular basis. Keep in mind these concepts work not only for an active shooter, but a train derailment, an airplane accident, or any large scale, multi-patient incident.

What’s Next?

As we look at where we have come and what we should be doing to prepare for the next attack, a few “realities” come to the forefront.

TEMS is not just for SWAT anymore. This is a paradigm shift that needs to be seriously considered. While the concept of “warm zone” only for emergency medical personnel is conceptually appealing, the reality is that TEMS-trained and equipped medical personnel are needed as close to the fight as possible to make a difference for our most seriously injured victims. A good example of this concept occurred during the synagogue attack in Pittsburgh where TEMS personnel saved lives during the hostile encounter.

Civilian and police officers shot during that event may not have lived without the medical intervention (the TEMS officers in the hot and “very” warm zones) were able to perform. Our medical personal already have (Las Vegas) and will be in the future operating in the hot zone with Police. Our next goal should be TEMS-trained and equipped medical responders who can work closely with patrol officers who are in the fight.

Although TEMS-trained paramedics are lifesavers, TEMS trained and equipped medical doctors are the gold standard. My team is extremely blessed to have a trauma surgeon and two emergency room doctors on our TEMS unit. While many may feel this to be a “bridge too far,” I continuously find doctors who are performing this mission and others who will gladly volunteer to join in this fight to save lives. Doctors on scene save lives. Work through the liability and medical authorization issues in your area, get them emergency response authority and get them on scene quickly.

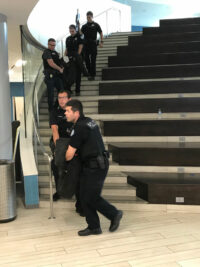

Dynamic, direct action small unit tactics and techniques need to be integrated into your patrol officer active threat training curriculums. Many agencies incorporate these into their MACTAC training, but the same needs to be done during rapid deployment (RD) training indoors. While we start our basic training with four and five officer teams to teach areas of responsibilities, search tactics, geometric angles, and team cohesion, we quickly transition to two- and three-officer contact teams.

The direct application of armed officers into the ongoing active threat situation is what continuously has been shown to make the difference. The ability to change the focus of the offenders’ actions from innocent civilians to responding law enforcement as quickly as possible saves lives. But our officers must be trained and equipped to perform this type of operation. Tactical, realistic live fire training is also a missing component in many departments tactical active threat training. Flat range, linear training does not meet the standard. If your expectation of performance includes your officers doing flanking, bounding, and fire and maneuver tactics to save lives, then they should do it in live fire training.

Every community is full of soft targets. Although most departments train in schools, churches, shopping malls, and commercial office type buildings; have you trained your patrol officers the basics of bus and passenger train entry and clearing tactics? These transportation conveyances are the softest of targets that will be attacked. Once your officers are competent in the traditional soft targets, have a go at the transportation targets in your jurisdiction. Don’t expect them to reach SWAT team hostage rescue performance levels, but they should have the basics and experience the environment before they have to do it in a crisis situation.

All incidents are different and the decisions made on the scene must be done in a unified command process evaluating the situation, circumstances, environment and threat. Police and fire bosses need to decide “What is important now?” and then carry out the best strategy to address the problem identified. Develop a solid joint standard operating guideline for your fire and police departments that provides the guidance and expectations on how these situations will be handled. We all hope we never have to face an active shooter event, but if it happens, the victims are depending on us to save their lives.

Alan Berkowsky has been in the fire service for 39 years. He started his career with the Chicago (IL) Fire Department as a Paramedic. He then joined the Evanston Fire Department in 1981 as a firefighter/paramedic and then became chief of department in 2004. Retiring from the Evanston (IL) Fire Department in 2010, he became fire chief for the Winnetka (IL) Fire Department in 2011 and is currently serving in that capacity.

Edward Mohn has been a police officer for 30 years. For 24 of those years, he has served with the Northern Illinois Police Alarm Systems Emergency Services Team (NIPAS-EST), the largest multijurisdictional SWAT team in the United States, providing SWAT services to 70 communities in Northern Illinois. As the teams entry team leader, assault force commander, and now as tactical commander, he has planned and led his team in the successful resolution of over 600 critical incidents. He has been highly decorated for his actions, and has been the lead instructor and statewide coordinator for the ITOA’s rapid deployment/immediate action response to active threat training efforts for 18 years. Prior to starting his career in law enforcement, he served five years as an infantry non-commissioned officer with the 1st Infantry Division, 16th Infantry Regiment, United States Army.