BY ANDREW GRAVES

Abandoned building fires are a significant problem for fire departments across the country. Abandoned buildings present a ready target for arsonists and a hazardous environment for firefighters. They have a minimal value to the community even before they are damaged by fire and are havens for crime, blight, and vandalism that reduce the value of nearby properties.

Flint, Michigan, is plagued by frequent fires in vacant and abandoned buildings. Annual Federal Bureau of Investigation crime statistics gave the city the dubious distinction of being ranked number one in per capita arson for cities with a population of more than 100,000 in 2010 and 2011. An internal study conducted in Flint during 2007 identified a high rate of firefighter injuries at abandoned building fires. The national average rate of firefighter injury is 3.7 per 100 incidents, as reported by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). Flint’s rate of injury was 11.7 per 100 incidents at the time of the 2007 study. Sixty-two percent of Flint’s firefighter injuries occurred at abandoned building fires.

Operational Considerations in Abandoned Building Fires

The Flint Fire Department (FFD) responded to the study by implementing a new abandoned building policy in August 2007. The policy recommended that officers make more frequent use of defensive and transitional strategies at abandoned building fires. The policy also provided officers with the authority to concede a heavily involved abandoned building as lost and not savable, with efforts then being directed to protect exposures.

In November 2012, a second study was conducted on firefighter injuries at abandoned buildings. The study examined 10 years of fires and injuries in Flint, five years before and five years after the abandoned building policy. The results of the study illustrate the effectiveness of risk management for firefighters at abandoned building fires. Fire departments confronted with fires in abandoned properties should discuss, design, and implement a similar policy that incorporates the rule of engagement guidelines in NFPA 1500, Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program.

BACKGROUND

Flint, Michigan, is an urban city covering a 34.1-square-mile area 70 miles north of Detroit. Incorporated in 1855, Flint became a major hub of the automotive industry in the early 1900s. The city’s population grew to a peak level of nearly 200,000 in 1960. Its automotive factories once employed 80,000 people. In the late 1960s, a pattern of downturn began. Manufacturing jobs moved away from Flint, and the city began experiencing economic pressure amidst a declining population and tax base.

The FFD has seen a similar pattern of change mirroring the city’s growth and decay. In the 1970s, the department staffed 10 fire stations with nearly 300 fire suppression personnel. The diminishing tax base caused numerous layoffs, station closings, and staffing reductions through attrition.

Today, the department staffs five fire stations with 86 fire suppression personnel, 39 funded by a federal Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response (SAFER) grant set to expire in 2014. Voters in Flint recently passed a public safety millage that will be used to offset the impact of the SAFER grant’s expiration.

POLICY STUDY Defining “Vacant” and “Abandoned”

Within the fire service, use of the term “vacant” most commonly includes both vacant and abandoned buildings. The prime focus of this study is abandoned buildings. The 2007 City of Flint policy defines abandoned buildings as “a property that has no legal occupants and is neglected with no efforts made to preserve its value or condition.” (City of Flint, 2007)

The policy defines vacant buildings as “a property that has an owner but no permanent occupants, with reasonable efforts being made to preserve its value and condition.” (City of Flint, 2007)

Data Collection and Analysis

For this study, data were collected from the city’s fire records software. On conclusion of a structure fire incident, the reporting officer enters data about the fire incident into the records system. The data were reviewed and compiled into a database. Data were recorded about the following subject areas:

- The date of the incident.

- The time the incident occurred.

- The internal department run number for the incident.

- The street address or intersection of the incident.

- Whether the affected structure was vacant or occupied.

- The firefighting strategy and tactics used at the incident: an offensive fire attack at a vacant building, a defensive fire operation at a vacant building, or a transitional fire operation at a vacant building.

- An incipient stage fire at a vacant building.

- Fire affecting only the exterior of a vacant building.

- Whether the fire occurred at an occupied building.

- Whether the incident occurred before or after the 2007 policy.

- Whether a firefighter injury occurred during the incident.

- The number of firefighters injured during the incident.

- The ranks of the injured firefighters.

- The hourly pay rate of the injured firefighters.

Injury data were collected from the city’s Employee Health Clinic. The clinic records data about firefighter injuries on the MI-OSHA (Michigan Occupational Safety and Health Administration) 300 Log of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses form. Data were recorded from these forms into a spreadsheet in the following areas:

- The type of injury suffered by the firefighter.

- The number of eight-hour days the firefighter was on complete work restriction and unable to work.

- The number of eight-hour days the firefighter was on a light-duty work assignment.

- The total cost of complete work restriction time.

- The total cost of light-duty work assignment time.

- The combined total cost of complete work restriction and light duty time.

The cost of injuries was calculated by multiplying the affected employee’s hourly pay rate by the total number of hours on work restriction or light duty. Injuries were classified into one of 15 categories depending on the nature of the injury.

The city’s property tax Web site (http://cityofflint.com/propertytaxes/search.asp) was reviewed between August 29, 2012, and September 4, 2012. The city lists the current status of properties on this site. For each property classified as vacant by the reporting officer, the property tax records were reviewed. The status of the property was entered into the database as follows:

- The affected property has been demolished.

- The affected property is currently on the city’s demolition list.

- The affected property is posted as not inhabitable until repaired to code.

- The affected property still contains an improved structure.

The property status review comprised 2,095 separate properties; 213 properties were listed as improved. To determine the status of improved properties, site visits were conducted at each of the 213 improved properties between August 29, 2012, and September 4, 2012. The properties were visually inspected from the street or sidewalk. Properties listed as “improved” in the database were recategorized in the database after site visits as follows:

- The affected property is currently occupied by residents.

- The affected property is currently vacant and reasonably maintained.

- The affected property is currently abandoned and dilapidated.

During site visits, assumptions were made to determine if the property was vacant or abandoned. Properties that showed any reasonable sign of recently being cared for were listed as vacant. Properties that were found unsecured, boarded up, lacking energy utility connections, or in a visible state of dilapidated disrepair were listed as abandoned.

FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS Structure Fire Volume and Firefighting Tactics

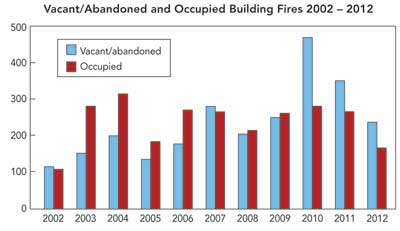

Analysis of the data shows distinctive changes between the pre-policy and post-policy periods. The FFD responded to 5,233 working fires during the 10-year survey period: 2,578 working fires occurred in vacant or abandoned buildings, and 2,655 working fires occurred in occupied buildings. There was a marked increase in vacant and abandoned building fires in the post-policy period, 1,623 vacant and abandoned building fires compared to 955 in the pre-policy period, a 70 percent increase.

Vacant and abandoned building fires represented 41 percent of total structure fires in the pre-policy period and increased to 56 percent of total structure fires in the post-policy period. These fires, at their lowest annual frequency, represented 35 percent of total structure fires in 2003 and, at their highest annual frequency, represented 63 percent of total structure fires in 2010. Figure 1 depicts vacant, abandoned, and occupied building fires during the survey period.

| Figure 1. Total Building Fires |

|

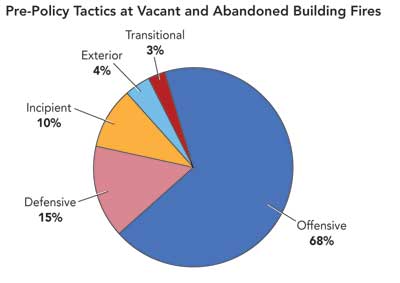

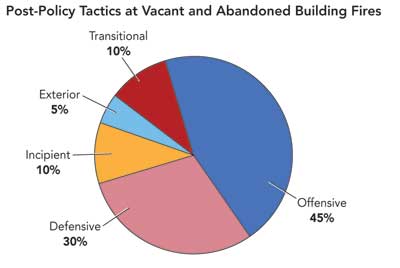

Firefighting tactics used at vacant and abandoned buildings changed in the post-policy period. Offensive attacks at vacant and abandoned buildings decreased from 68 percent to 45 percent. Defensive operations increased from 15 percent to 30 percent. Transitional operations increased from 3 percent to 10 percent. Structure fires at which incipient or exterior fire conditions were found were essentially unchanged between pre- and post-policy periods. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the change in firefighting tactics at vacant building fires before and after the policy.

| Figure 2. Pre-Policy Tactics |

|

| Figure 3. Post-Policy Tactics |

|

Offensive attacks were used less often as the primary strategy of choice. An examination of tactics over the 10-year study period shows a steady change in firefighting strategy. In 2003, offensive attacks at vacant and abandoned building fires were used 77 percent of the time. By 2012, offensive attacks decreased to 33 percent. In 2012, defensive strategies were used most frequently at vacant and abandoned buildings.

CIVILIAN LIFE SAFETY AND PRESERVATION OF PROPERTY

The two primary goals of firefighting are saving lives and preserving property. A review of fire records finds that the chances of a civilian being injured or killed during a vacant or abandoned building fire in Flint are exceedingly minimal.

In the study period, there were 2,578 working fires at vacant and abandoned buildings and four documented records of a civilian injury or fatality at a vacant or abandoned building fire. These four cases represent 0.16 percent of all vacant and abandoned building fires. At the remaining 99.84 percent of vacant and abandoned building fires occurring in the study period, the life hazard risk applies exclusively to the firefighters who respond.

Firefighters responded to 2,578 separate fire incidents at 2,095 vacant or abandoned properties. A review of the city property tax records and site visits to these properties found the following:

- 1,352 properties were demolished (64.5 percent).

- 412 properties are on the active city demolition list (19.7 percent).

- 118 properties are posted as uninhabitable until brought up to code (5.6 percent).

- 77 properties are in a dilapidated, abandoned condition (3.7 percent).

- 113 properties are in a reasonably maintained vacant condition (5.4 percent).

- 23 properties are occupied (1.1 percent).

Fires in vacant or abandoned buildings represent a minimal chance of preserving a viable property. During the study period, 93.5 percent of vacant or abandoned buildings suffering a fire incident were not repaired or rehabilitated.

FIREFIGHTER INJURIES

During the 10-year survey period, 155 firefighters suffered injuries at vacant or abandoned building fires. The number of firefighter injuries was nearly evenly split before and after the policy: 76 injuries occurred in the pre-policy period, and 79 injuries occurred in the post-policy period. At first glance, this would appear to indicate that the policy was not effective in reducing firefighter injuries. A closer examination reveals that there has been a notable change in the frequency and severity of firefighter injuries.

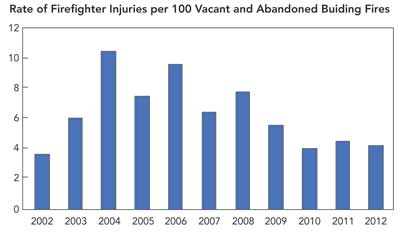

The NFPA reports that the national average for firefighter injuries is 3.7 per 100 vacant building fires. In Flint, the rate of injury during the survey period is represented in Figure 4.

| Figure 4. Firefighter Injuries |

|

There has been a decrease in the rate of firefighter injuries. With the exception of the four-month portion of 2002 within the survey, the lowest rates of injury were encountered in the post-policy period. During policy implementation, some firefighters and command officers initially resisted increasing defensive operations. Over time, the acceptance of the change to defensive measures became successful. Injury rates remained high through 2008 and then showed a stable pattern of reduction.

Note that while the number of injuries remained consistent in the pre- and post-policy periods, the number of vacant and abandoned building fires did not. There were 76 injuries at 955 vacant and abandoned building fires before the policy, an injury rate of 8.0 per 100 vacant and abandoned building fires, and there were 79 injuries at 1,623 vacant and abandoned building fires after the policy, an injury rate of 4.9 per 100 vacant and abandoned building fires.

Work Restrictions

Firefighter injuries result in two types of injury-related time off duty: complete work restriction and light-duty restriction.

Firefighters on complete work restriction are not able to perform work in any form, whereas firefighters on light-duty restriction may work in a reduced capacity but may not engage in firefighting activities. Light-duty work restriction involves administrative or clerical assignments until the injured firefighter has recovered completely and is restored to firefighting duties.

In the 10-year survey period, 155 firefighter injuries at vacant building fires resulted in a cost of $374,272 for complete and light-duty restriction hours; in the pre-policy period, 76 injuries cost a total of $236,905; and in the post-policy period, 79 injuries cost $137,367.

The average pre-policy cost of work restrictions was $3,117 per injury; the average post-policy cost was $1,739 per injury. The post-policy period saw a reduction of $1,379 in the average total cost per injury.

The city incurred a cost of $138,971 for complete work restriction hours in the 10-year survey period. In the pre-policy period, complete work restriction cost a total of $115,423 or $1,519 per injury. In the post-policy period, complete work restriction cost a total of $23,548 or $298 per injury. The post-policy period saw a reduction in the cost of complete work restriction of $91,875. The average cost of complete work restriction decreased by $1,221 in the post-policy period.

The city incurred a total cost of $235,301 for light-duty restriction hours in the 10-year survey period. In the pre-policy period, light-duty restriction cost a total of $121,482 or $1,598 per injury. In the post-policy period, light-duty restriction cost a total of $113,819 or $1,441 per injury. The post-policy period saw a reduction of $157 in the average cost of light-duty restriction per injury.

Injuries in the post-policy period were less frequent and less severe than in the pre-policy period. The drastic reduction in the cost of complete work restriction time while structure fire volume dramatically increased illustrates the effectiveness of the policy.

Burn Injuries

Given the nature of firefighting, firefighter burn injuries are worthy of specific attention. Thirty-four burn injuries occurred in the survey period, and 24 burn injuries occurred in the pre-policy period. In the pre-policy period, 24 burns resulted in 168 days lost on complete work restriction. Pre-policy burns resulted in 171 days lost on light-duty restriction.

Every burn in the pre-policy period caused some form of injury-related time off. Burn costs in the pre-policy period were $54,533—$29,193 for complete work restriction and $25,340 for light-duty restriction. The average burn in the pre-policy period resulted in seven days on complete work restriction at a cost of $1,216. The average burn in the pre-policy period resulted in 7.125 days on light-duty restriction at a cost of $1,056. In the pre-policy period, there were two instances in which more than one firefighter was burned at the same incident.

In the post-policy period, burn injuries sharply decreased. Just 10 burns occurred in the post-policy period. The total cost of time lost to burn injuries was drastically reduced in the post-policy period: 10 burns resulted in nine days lost on complete work restriction. Post-policy burns resulted in 32 days lost because of light-duty restriction. One of these burn injuries resulted in eight days on complete work restriction and nine days on light-duty restriction. Three post-policy burn injuries resulted in zero time lost to complete or light-duty restriction.

Burn costs in the post-policy period totaled $6,564. Post-policy burns resulted in costs of $1,434 for complete work restriction and $5,130 for light-duty restriction. The average burn in the post-policy period resulted in 0.9 days of complete work restriction at a cost of $143. The average post-policy burn resulted in 3.2 days of light-duty restriction at a cost of $513. There were no instances of multiple firefighters being burned at the same incident during the post-policy period.

The cost of burn injuries decreased by a total of $47,969 in the post-policy period. A firefighter suffering a burn in the post-policy period spent 6.1 fewer days on complete work restriction and 3.925 fewer days on light-duty restriction, on average. The cost of complete work restriction decreased by $1,073 per burn injury, on average. The cost of light-duty restriction decreased by $542 per burn injury, on average. The most severe pre-policy burn resulted in a cost of $12,109 for complete and light-duty restrictions. The most severe post-policy burn resulted in a cost of $2,709 for complete and light-duty restrictions.

Burn injuries decreased as firefighters adjusted to using defensive and transitional operations at vacant and abandoned buildings. Prior to the policy, all structures received offensive attacks whether occupied, vacant, or abandoned. The only exceptions to this method were fully involved vacant and abandoned buildings or buildings with obviously hazardous structural instability. Firefighters were repeatedly exposed to avoidable risks during offensive attacks that resulted in more frequent and more serious burns in the pre-policy period.

Offensive attacks present the highest level of risk for firefighter injury. The policy directs firefighters to use offensive attacks only for minimal to moderate fire conditions or if there is a confirmed civilian life in jeopardy at a vacant or an abandoned building. Offensive attacks decreased at vacant and abandoned buildings from 648 (68 percent of 955 abandoned building fires) pre-policy to 721 (45 percent of the 1,623 abandoned building fires) post-policy. The frequency of burn injury dropped from 1 in 40 vacant and abandoned building fires pre-policy to 1 in 161 vacant and abandoned building fires post-policy.

This study has shown a direct correlation between the 2007 policy and a reduction in firefighter injuries. Risk management policies are an effective tool for fire departments confronted with fires in abandoned buildings.

Fires increased from 955 in the pre-policy period to 1,623 in the post-policy period, yet the rate of injury decreased.

Risk management policies should be considered and implemented in any locality faced with fires in vacant and abandoned buildings. This study has shown the 2007 policy to be effective in improving fire department operations and reducing injuries and their related costs.

Firefighting is inherently dangerous, and injuries will never be completely prevented. A risk management policy for vacant and abandoned buildings can greatly reduce that inherent danger and create a safer environment for firefighting operations.

ANDREW GRAVES is a 23-year veteran of and a retired battalion chief from the Flint (MI) Fire Department. The study featured in this article was the capstone project that completed his work for a master of public administration degree at Eastern Michigan University.

More Fire Engineering Issue Articles

Fire Engineering Archives