5-Unit Strike-Team Mutual Aid Plan Is ‘Limited Only by Your Imagination’

“What this mutual aid system will do for you is limited only by your imagination. That’s what we tell new chiefs coming into office in these communities.”

So said Chief William Stremme of Hillsborough, Calif., in describing the five-level program covering the San Mateo County peninsula just south of San Francisco.

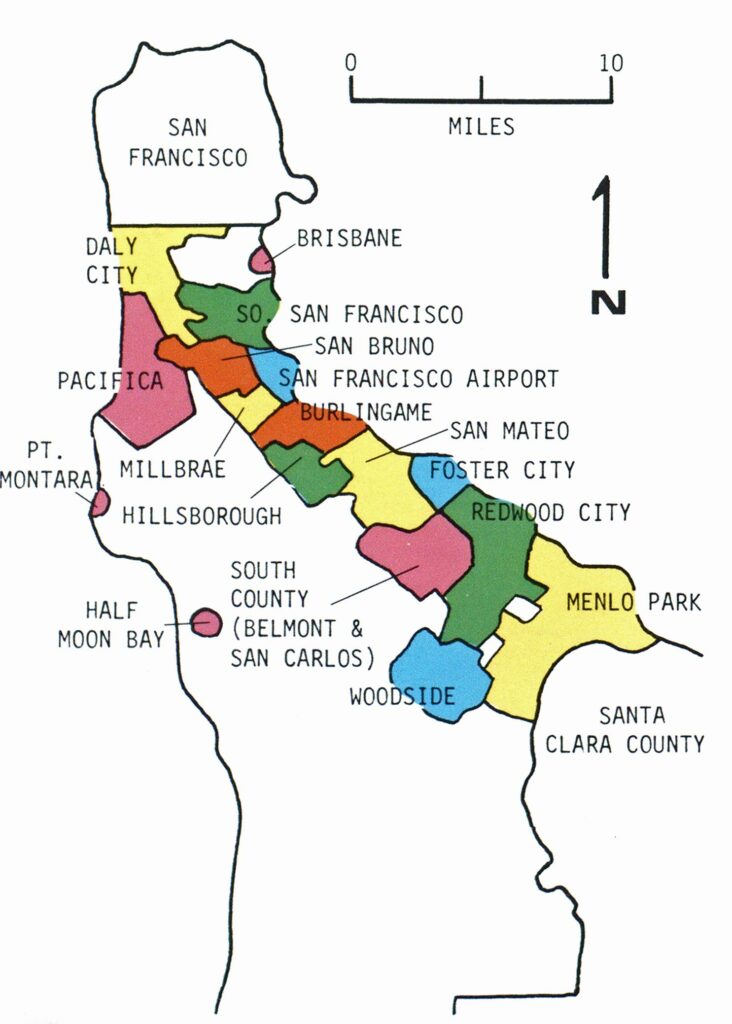

That program has to be versatile and flexible. San Mateo County’s 600,000 residents are largely concentrated in a narrow urban strip along 30 miles of San Francisco Bay shoreline. Here, 14 separate cities blend indistinguishably into each other, presenting every kind of fire and rescue hazard from high-rises through exotic electronics industries to a major international airport. Several other more isolated towns lie across a mountain ridge on the ocean side of the peninsula.

The entire county occupies 447 square miles from bay to ocean. Three-fourths of that is rugged wildland, with few access roads, in extreme forest and brush fire danger throughout much of the year. That rural territory, plus a number of urban islands among the peninsula cities, is protected by the California Division of Forestry (CDF) from five fire stations. The communities themselves are covered by 16 municipal fire departments, or districts, plus five small groups of volunteers.

Extensive mutual aid

All those agencies are now involved in a system of mutual aid which extends from the movement of a single piece of apparatus across a nearby boundary to help the next town all the way to intercounty teams available for dispatch hundreds of miles away.

Stremme, who was elected in 1978 by the San Mateo County Fire Chiefs as the county’s mutual aid coordinator, declared that “no city can afford the manpower you may need for the emergencies possible in this area.” His aides in administering the system are Chiefs Vince Del Pozzo of Menlo Park, John Bettencourt of Foster City and “Dutch” Moritz of Brisbane.

The program’s first two stages, in operation for many years, are common throughout California and elsewhere. One is the “day-to-day working agreement” whereby any particular emergency units needed by one community will be sent to another upon request. A typical example is a second aerial, or elevating platform, for a high-rise incident in a city having only one such unit.

The second level of help is “automatic aid” for boundary areas. Borders between cities, or outlining the CDF islands, form such a crazy quilt that often apparatus in City B is closer to a fire in City A than is A’s fire department. In the brush area near the hilltops along the peninsula’s spine, rapid fire spread usually calls for companies to work together over a large territory. Hence, in many parts of the county, an alarm automatically brings responses from two or more nearby cities as well as the CDF.

The third level is relatively new.

Explained Stremme, “Deputy Chief Emil Biagi of Redwood City and I sat down for a month and a half about 1973 to develop this concept, which was then affirmed by the county chiefs. It set up three task forces, or strike teams, along the peninsula, plus a smaller fourth one involving the coastal towns. Based on each community’s on-line resources, not counting reserve equipment, it was considered that a team would consist of five engine companies with at least three men on each. It is directed by a team leader, and is available to respond anywhere in the county when requested by the responsible chief officer at the location where it’s needed.”

The chart shows how the teams function. In the southern part of the county, for example, a call for a strike team activates the closest one first—the South County Task Force. Because one engine for that team comes from each of five different departments, no single outside city loses all its equipment when the team is dispatched. Normally, all engines available in the city where the emergency occurs will have been committed when the team is called.

“Our departments are all small,” added Stremme. “I have only two-man engine companies in Hillsborough. But if anybody doesn’t have the required three men to send with a strike team engine, it’s up to that department to get the extra people any way it can. I do it by calling in off-duty men. Generally, we have such people respond directly to the fire.

“We set it up that way so the incident commander at the scene would always be able to tell exactly what manpower and equipment he could expect to get when he called for a strike team.”

Volunteers in backup role

The only direct team participants are the county’s paid fire services. Altogether, the available force includes 63 engines plus 11 aerial or platform units, operating from 54 stations.

But the volunteers aren’t left out. Said Stremme, “We use them as backup. If we have to start stripping cities by pulling together two or three strike teams, the volunteer units are assigned to take over responsibilities bordering their own service areas. They become a gap-filler. For instance, up in the hills behind us is the Kings Mountain Volunteer Fire Brigade. If the Division of Forestry is stripped by a major strike team incident, Kings Mountain becomes the first-line response into the nearby forestry territory. If the City of San Carlos loses an engine to a strike team when the whole county has been activated, a volunteer group in the hills behind San Carlos becomes first-due on any fire in the city.”

In the Central or North County, the CDF becomes the gap-filler. That was true in the southern peninsula, too, until San Carlos and Belmont consolidated their fire protection so that only one strike team engine became available from there instead of two. The CDF was put on the South strike team to make up that loss.

Some team calls require no service. For example, a July 1980 electronics plant fire involved chemicals of uncertain properties. A strike team was summoned, stood by for an hour, then was released when the emergency was over.

“A few years ago,” according to Stremme, “the CDF had a major brush fire in a heavily populated area. They asked us for everything we could send, so we stripped the city and then called in a strike team to cover for us. In other situations, we have covered CDF stations with a strike team while they handled the fire.”

Continued Stremme, “There really isn’t any extensive formal agreement on this. It’s all been done on a handshake. But it works.”

There have been numerous successful tests of the system. The most recent was a million-dollar cannery fire May 21, 1979, in Redwood City. That sevenhour incident brought out a total force of 18 engines, four trucks, and 108 men. Three of Redwood City’s four engines and its only truck company were committed on two alarms. Four minutes after the initial call, the South County Task Force and the nearest available aerial were requested. Engines from Woodside, San Carlos, Belmont, and the CDF responded along with an engine and a truck from the Menlo Park Fire Protection District, which serves three cities at the county’s extreme southern end.

Second team called

Because Redwood City had almost nothing left in service, the next closest strike team—Central County Task Force—was called two minutes later (plus another truck) to occupy the city’s vacant fire stations. However, by the time it arrived, it was needed at the fire itself. The North County Task Force was then brought in to cover the city. Most of its units had 20-mile runs.

Stremme stated that, despite the distance, “we don’t have a moveup system. We set things up so that no one community would lose too much of its resources by responding with a strike team. It’s tougher over on the coast, of course, because of the greater distance and poorer roads. So we tell the people over there, if you ever think you will need a team, get it going right away.”

As in the Redwood City incident, teams may be used either for fire fighting or cover-in duty. It’s up to the requesting authority. When sent to cover a community, the team units normally meet at a single rendezvous point to get their instructions. Universally used map coordinates locate such points for each unit dispatched.

“But you can’t rely on maps alone to get around unfamiliar cities,” Stremme pointed out. “So covering units are always given a pilot. Once when we had a team filling in for us, I called in three off-duty men to act as guides. We say, when going into another city, give us somebody to get us around and we’ll do the job. We don’t care who it is—could be somebody from the parks or water department, or a building inspector—so long as he knows the city.”

Aid frequency used

Strike team dispatching is normally done from Menlo Park. Backup dispatch location is in the City of San Mateo. To request a team, the incident commander uses the “white frequency”—a statewide mutual aid frequency of 154.95 Mhz. The team responds as a single unit, operating on that same frequency. When no longer needed, the team companies are released as a unit to return to their quarters.

Most apparatus in the county carry at least 500 gallons of water, some as much as 1000. But for wildland fires, off-road mobility is also important. So Menlo Park Fire Control has records of a special team of 10 four-wheel drive vehicles to call on. Specialized rescue units can also be sent as part of a strike team.

This sometimes crosses county lines. For example, a 1978 chemical plant leak in South San Francisco threatened an explosion unless large amounts of carbon dioxide were brought in to cool down a reaction. After using all the CO2 in the area, the city asked for countywide help. All available 20-pound units were sent in. But much more was needed, so the fire/rescue coordinator in Santa Clara County, to the south, was contacted, and he located a 600-pound unit at a Naval Air Station. It was dispatched, under police escort, 40 miles to South San Francisco.

Photo by Steve Ehlers, Menlo Park Fire Protection District

Arson investigators available

“We even have an arson investigation team available to any community as part of our aid plan,” Stremme added. “There are 35 of us on call at a minute’s notice, including both police and fire services. For example, at one incident, South County wanted two men. We sent my battalion chief plus the fire chief from San Mateo. At a big church fire in Redwood City in 1979, five of us worked for four days on the investigation. The CDF is as much a part of this as any city in the county. They had two men at this fire, one of them a photographer. The County Chiefs have agreed, ‘If you need a man for four hours, or four days, you have him’.”

Asked about common training or fire fighting methods among the county’s agencies, Stremme replied, “We don’t formally activate strike teams for training. But there are many exercises throughout the year that do bring a team together. Here in Hillsborough, we drill regularly with San Mateo, Burlingame and the CDF. For instance, we may supply Burlingame’s ladder pipe at some fires, so we have to be familiar with that. Departments having such specific reasons are getting together on the best ways to help each other. An example in the joint dispatching we share with San Mateo and Foster City.

Now, still another cooperative effort is a joint powers agreement in the works to buy a mobile breathing air compressor. San Mateo, Foster City, Burlingame, Hillsborough, Millbrae and the CDF will all chip in $6000 apiece. This rig will fill a 45-minute bottle in three minutes, plus carrying 16 spare bottles. It would be a drain on any one department to man it all the time, so it will probably be based in San Mateo to start with and rotate around the communities a year at a time.”

San Mateo County’s fourth level of extra help for major emergencies is provided under the statewide Office of Emergency Services (OES) system.

Explained Stremme, “If I start running out of resources, I go to the OES fire and rescue organization. I can request engine companies from throughout California. There are 100 OES engines available altogether, two of them in this county. They are quartered, manned and operated by local fire departments on the condition that they be made available when needed elsewhere. Whichever fire department is housing the rig must provide a two-man crew to go with it when it’s called.

“One problem we had with our OES engines was the length of time they might be needed. I was at the Marble Cone fire up in the mountains for 23 days. It’s hard on a small community to have people away for that long even though it’s been worked out so that relief manpower is committed to rotate people out after seven days. So we are now rotating departmental responsibility for our OES engines between June 15 and October 15. Each one of nine departments in San Mateo County is responsible for one two-week period.

Six hours travel time

“Another problem is that you have to expect at least six hours travel time for these OES units because most of them are so far away from you. A few years ago in Northern California, 50 of these engines were working on major wildland fires. I, myself, was on a brush fire near Red Bluff with 10 engines. Marin County, north of San Francisco, then had a brush fire, used up what it had, and called OES for outside help only to be told that nothing would be available in under six hours. Individual cities and towns then stripped themselves to cover that county, and one of the cities then had a fire of its own.”

Continued on page 26

As a result, the 16 California counties in OES Region 2 (of which San Mateo County is a part and for which Stremme is assistant coordinator) got together to set up an intermediate level of aid. This is the “inter-county” system.

“San Mateo County has committed a five-engine strike team to any of the other 15 counties,” said Stremme, “for use up to six or eight hours. After that, other OES units from farther away should be able to come in and relieve us. This system includes engines only. For this, we don’t meet at any staging area, but proceed directly to the fire.”

Location of the San Francisco International Airport within San Mateo County, even though it has its own separate fire protection, has led to offshoots of the strike team program that make up the fifth kind of mutual aid response in the county.

First, a special five-engine team can be sent from neighboring cities onto the airport property. Normally, four of the companies would aid the airport’s own fire units at a crash site. The fifth engine would cover the vacated airport fire station. At the same time, San Francisco would dispatch two special teams of its own, but response distance for these is considerably greater than for nearby county apparatus. A second five-engine group is available from the county if necessary.

Drill at airport

Added Stremme, “Once a month we go in on the airport’s drill schedule to remain familiar with the territory, especially access routes. These drills take place at various hours day and night. Several times a year, San Francisco companies will also join in.”

A variation on this is the county’s “code 1000” air crash/rescue response. This was set up in August 1974 after several months of preparation and has not yet been put to use for an actual emergency, although several exercises have been held. Under the code 1000 plan, the initial attack force of 15 engines is sent to whichever community reports the crash within its boundaries.

“Here we have to get the equipment in fast,” Stremme declared, “because otherwise traffic and onlookers will block us out. At a crash in Alameda several years ago, mutual aid units couldn’t get within three blocks of the scene.

“So in this case, we do strip the nearby cities. For example, we may take two-thirds of San Mateo’s engines, or two out of Burlingame’s three. Then, we start moving others up by transfer. This works by teams.”

As an example, should the incident occur in Millbrae, here is the attack force response:

Providing the first-due company confirms the need for that force, a moveup team of five engines would then be dispatched to Millbrae’s Station 1, to cover that city:

The second fill-in team of five engines fills in this way:

Note the decrease in the percentage of each community’s equipment committed as that community’s distance from the incident increases.

Four-man teams

If the crash occurred in San Bruno, farther to the north, the largest share of the attack force (five engines) would come from Daly City, the closest neighbor with the most apparatus. That would strip Daly City. In that event, San Francisco would dispatch five engines to cover Daly City’s five stations, over and above any county coverage.

Four-man companies are required for code 1000 teams. A 1978 crash drill up in the hills, with many victims to be removed on litters, showed the impracticality of three-man units for that kind of work.

As with the normal strike team program, each team has a designated commander from one of the agencies involved. Code 1000 also activates the California Highway Patrol, local sheriffs, public transportation agencies— even the State Department of Transportation, by whose sole authority major freeways can be closed. Local police are alerted to seize overpasses or ramps at interchanges so that large areas can be isolated.

Thus, at every level of interagency cooperation—city, county, and state— the peninsula communities are prepared to make the best possible joint use of their available fire fighting resources.