BY MICHAEL N. CIAMPO

Across the country, firefighters use different tools to perform truck company operations. Normally, every truck company has a firefighter who is assigned forcible entry duties. This firefighter normally carries a set of irons—usually some type of a prying tool such as a halligan, claw, or pry bar “married” with a flathead ax, sledgehammer, or splitting maul. In some cases, the person assigned the forcible entry position may even carry a hydraulic forcible entry tool. However, when assigned other positions or tasks such as overhaul or ventilation, these firefighters may choose another type of tool or hook. In many instances, firefighters often carry two tools that complement each other and enable them to handle a variety of fireground situations.

Many fire departments may have a particular tool or hook that was created years ago and remains the mainstay or the “go to” tool in their department. Firefighters might have developed some of these tools with the idea of making an existing tool better or making work easier on the fireground. Many of these tools may look odd and can come in a variety of shapes, sizes, thicknesses, and forms. Even today, firefighters try to retrofit or redesign these tools to meet their needs.

Years ago, I was a research participant for Richard A. Fritz’s Tools of the Trade: Firefighting Hand Tools and Their Use(Fire Engineering, 1997). I was intrigued to see how many different styles, designs, and shapes of tools and hooks were used around the country. As I developed friendships with firefighters from across the country, I would ask, “Why do you use those tools?” The answers pointed to one reason: “They work for us in our types of buildings.” So let’s take a look at what works for some departments around the country.

NEW YORK ROOF HOOK

By Lieutenant Michael N. Ciampo

In the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), although every truck company is staffed with five firefighters and the officer, each individual firefighter carries a specific complement of tools. Each firefighter is assigned two tools and in some instances may carry more. In addition, most truck company firefighters carry a wide assortment of smaller hand tools (pliers, utility knife, utility rope, and 4-in-1 screwdriver) in their bunker coat pocket and also wear a rechargeable flashlight. A brief overview of the riding positions and tool assignments follows:

Officer: officer’s tool (pry bar/lock puller combination), thermal imaging camera (TIC), and search rope (if needed).

Chauffeur: tools of choice, depending on the tasks.

Irons:halligan, eight-pound flathead ax or maul, and hydraulic forcible entry tool.

Can: six-foot New York pike hook and water extinguisher (for top-floor fires, also two hooks—one for the irons firefighter).

Outside vent: six-foot hook (New York pike or roof) and halligan (in some situations, a set of irons or a power saw).

Roof:six-foot New York roof hook, halligan, lifesaving rope (in some instances, set of irons, a power saw, or a wind-controlling curtain device).

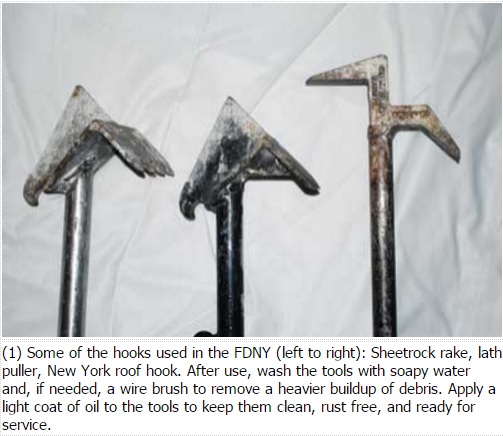

There may be some operational differences and tool choices for companies around the city because of the different types of structures they respond to on a daily basis, but these are the normal truck company tool assignments. Although a few different styles of hooks are used (New Yorker pike pole, New York roof hook, multihook, lath hook, and Sheetrock rake), one specific hook is able to handle almost all of the tasks: the New York roof hook (photos 1, 2).

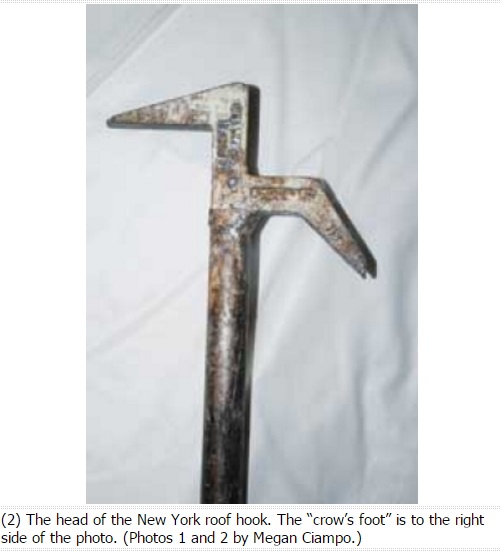

The hook is fashioned similar to a large crow bar in that it is made to act as a lever when prying off window or door moldings or prying up roof or floor boards. When removing roof boards, slide the head on top of the roof joist and under the roof boards, and then push away from you to pry up the material. When it is difficult to put the head under the roof boards, place the head next to the joist and under the roofing. Next, use the joist as a fulcrum, with the point of the hook on top of the joist. You can then lift the tool’s handle, and the prying motion causes the roof boards to release from the joist. Note that if you are pulling up the roof planking instead of prying it up, hold the hook in the proper position. When you pull the boards upward, one side of the head is designed to give the most advantageous pressure upward, compared with using the opposite end.The standard size firefighters carry is six feet; other sizes are stored on the apparatus. The head is made of cast metal and is welded to an aircraft steel metal pipe handle that has nonslip grips. On the opposite end of the shaft is a chisel end that extends up into the handle for greater strength and is welded to the handle. The hook is made of steel, but it is comparable in weight to a fiberglass-handle hook. The hook has a head with two different-shaped chiseled ends, one tapered side and one flat side, and a pointed top.

At vacant building fires, you can use the hook to pry off some types of plywood window coverings for access/egress and ventilation. Use the short portion on the hook’s head, between the horizontal and vertical sections, to help release the vertical drop ladder on fire escapes. Also use the hook’s head (the straighter end, opposite the crow’s foot) for pulling open plaster and lath and gypsum walls and ceilings, although you can use either side in certain instances. To open up tin ceilings, it may be better to use the crow’s foot end to penetrate the tin. You can use the hook’s head to pry open outward-opening doors and force some inward-opening doors, but most roof firefighters use the halligan. A roof firefighter working alone can use the halligan and roof hook together to force an outward-opening door (photo 3).

|

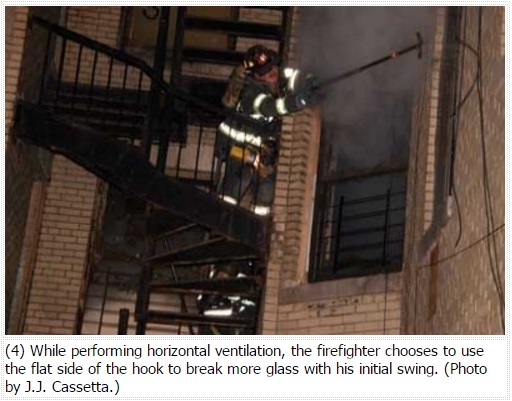

The flat side of the hook’s head is good for opening up skylights on dumbwaiter shafts and elevator and roof bulkheads found throughout the city. Run the flat side up the side of the shaft or bulkhead and get underneath the flashing material. Then either push upward or pry outward with the hook to release the flashing and the skylight attachment points. During overhaul in lath-and-plaster occupancies, use the hook’s flat side to strike the wall to break off the plaster from the lath. If you are venting a window with the hook, either side of the hook’s head will perform with the same results. If you are venting windows from the floor above, it may be better to use the sharp chiseled end. When opening up ceilings or cutting relief cuts into gypsum walls, thrust the pointed head through the material to cut it or to create a purchase point for the hook’s head (photo 4).

|

Opposite the hook’s head at the butt end, a chisel is welded up into the handle of the hook. Originally, a firefighter’s ingenuity helped create this feature; the ends of tire irons found in old abandoned autos were welded onto the hook’s handle. Some uses for the pry bar end include the following:

- Pry off baseboard and crown molding.

- Pry up a sidewalk cellar door hatch.

- Pry up the flashing of a skylight.

- Make an initial purchase point into a ceiling.

- Act as a digging bar.

- Probe roof surfaces as you advance.

- Pry open doors and keep purchase points open.

- Break open skylights and draft-stops.

- Pry plywood off vacant buildings.

- Pry off sheathing, shakes, siding, and shingles.

- Vent windows covered by security grating.

Sometimes this hook has a metal chain link welded near the chisel end. This link enables the connection of a hook and halligan, allowing the roof firefighter to vent windows from the floor above or the roof. Maintenance of the hook is fairly simple: Keep the edges sharp and sand, file, or grind down any burrs on the handle. Rub a light coat of oil on the tool head to prevent rust. Some companies have added the forked end of a halligan bar at the pry bar end or incorporated two different hook heads at each end. This hook offers firefighters numerous capabilities when operating in a variety of structures throughout the city.

Along with a hook, most firefighters in New York also carry what some consider the premier fire service tool: the halligan. An updated version of this tool is perhaps the most versatile tool in the FDNY’s arsenal and the one we rely on the most.

BOSTON RAKE AND ADZ

By Lieutenant Steve Mitchell

Boston, Massachusetts, is a very old and congested city. Some of the firefighting tools we use we consider unique—specifically, the Boston rake and the wrecker’s adz, Boston adz, or simply “the adz.” Both of these tools are the mainstay of firefighters assigned to open up at fires.

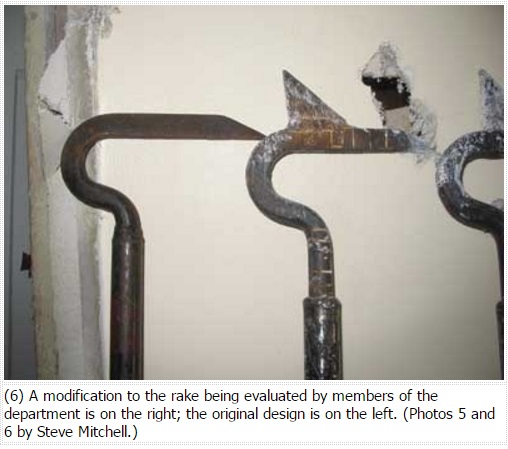

The Boston rake is like a pike pole in that we use it to open up walls and ceilings, break windows, and pull up roofing materials. It has a fiberglass handle with a rubber sleeve to help prevent slipping. The most common length of the rake is six feet, but ladder companies carry sizes up to 14 feet (the church rake). What is unique to the tool is its thin gooseneck head, which is approximately seven inches long with a 45-degree angle on its end. The head is also beveled along the bottom, and we keep it sharp so it bites into the material we are pulling down. The long head assembly allows us to pull large sections of lath and plaster when opening ceilings (photo 5).

|

The head is large and sometimes difficult to force through a ceiling or gypsum placed over lath and plaster. In these cases, we force the butt end of the hook through the ceiling first to make an entry point for the hook’s head. When inserting the hook into the ceiling, we make sure the long portion of the hook’s head faces away so any pulled ceiling material falls out in front of and not on us. Department members have made recent modifications to the hook’s head to make the tool more user friendly—for example, welding a small triangular piece of steel to the top of the tool’s head to help gain an initial purchase into the ceiling. We are still evaluating this modification (photo 6).

|

We also use the rake to pry molding and trim from around doors, windows, and baseboard, although we often prefer the adz for those tasks. The head’s 45-degree angle acts as a fulcrum when the point of the hook gets behind trim. We then apply pressure in whichever direction necessary to use the hook as a giant pry par. The rake is very effective for venting windows. Its large head breaks a large section of glass on impact. Unfortunately, the large head can get caught on cable or wiring when opening up walls and ceilings, and we may have to reposition it. During roof operations, the tool head can pull the roofing and sheathing off the roof. Then, turning the rake upside down and holding onto the gooseneck, a firefighter can push the top-floor ceiling down to complete ventilation. This prevents the large head from getting stuck on wire, cable, pipes, or ductwork during ventilation. A smaller version of the rake is called the closet rake. It is approximately three feet long with a “D” handle on the end. Normally, all the other rakes are equipped with a gas shutoff end on the butt portion of the hook.

The adz is by far the most versatile tool. With our older building construction, thousands of 21⁄2- and 31⁄2-story wood-frame dwellings, and our “triple deckers,” gaining access to the seat of the fire and stopping fire extension are extremely important. The adz can help us with that task in many ways. It can do everything that a halligan, ax, or pike pole can do. It can force doors, strike a halligan, act as a sledgehammer, pull ceilings and walls, break windows, gap a door for insertion of a hydraulic forcible entry tool, open roofs, and remove door and window trim.

The adz was developed in Massachusetts in the 1920s and introduced to our department in the 1970s by Ladder Co. 7. The tool’s head assembly is a thin steel blade that is 15 inches long and 21⁄8 inches wide; the tool weighs five pounds and has a hickory handle. The opposite end of the tool has a small hammer-like head, which we use for striking objects. A modified version of the adz that may be more beneficial for firefighting operations is in development (photos 7, 8).

|

|

The power of the tool is in its leverage. Insert the blade into a door (like the adz end of the halligan bar) to gap the door. Next, rotate the handle downward toward the floor to gap and force the door. Do not push or pull the tool’s handle in other directions when forcing a door. The 21⁄8-inch blade will create enough force and pressure to force the door as you turn the handle toward the floor. During its initial introduction to the department, we saw the tool’s power when the ladder truck’s jack was lowered on the adz. Then the adz was rotated to the floor, and it lifted up the truck. We use the same concept of rotating the handle to remove door frames, window and door moldings, and floorboards during overhaul. Remember that the tool is designed for sideways leverage, not prying. If you use the tool incorrectly, it will be useless, and the handle may break.

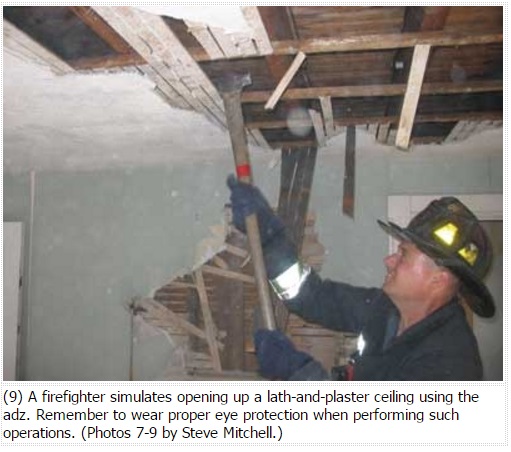

When coupled with a halligan tool, these two tools become a formidable forcible entry punch in the ladder company’s arsenal. You can also use the adz to open up walls and ceilings made of lath and plaster. It’s light enough to use repeatedly overhead. It is also of tremendous value in sliding in between double closing doors (common in storefronts): Simply insert the blade and use a little finesse and leverage, and you will open the door without causing any damage (photo 9).

|

We also use the adz for peaked-roof operations, and it fares better than an ax. There is less chance of the adz sticking in the tar in three layers of shingles, especially when compared with a pickhead ax. Depending on the roof’s pitch, you have to use short, concentrated swings while opening up the roof. We use the adz at auto extrications and elevator removal operations. It can also be found in some of the engine companies’ complement of tools. The adz doesn’t replace a tool like the halligan, but it does offer additional options for ladder company operations.

SAN FRANCISCO HOOK

By Firefighter Al Hom

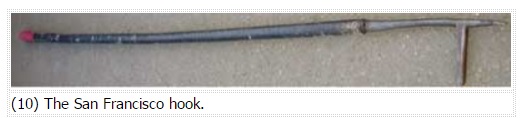

Truck companies in the San Francisco Fire Department are staffed with one officer and four firefighters. At the beginning of each shift, one of the firefighters is assigned to carry a ceiling hook at all fire incidents. The incidents range from a residential building alarm that is under investigation to a fully involved structure fire. The ceiling hook is considered a push/pull tool. Its main purpose is to open ceilings and walls to look for fire extension (photo 10).

|

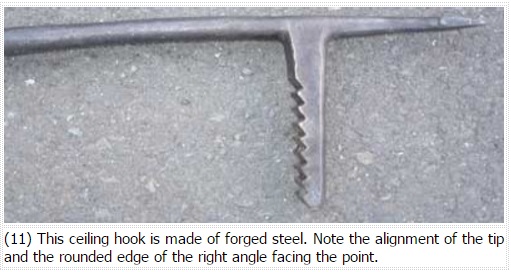

Currently, San Francisco has two versions of the ceiling hook on its apparatus. One version is heavier and made of forged steel with a simple design. The hook is essentially a straight pole approximately 84 inches long with a diameter of 11⁄2 inches at the shaft. The head of the pole is narrowed, and the tip is tapered to the shape of a flathead screwdriver. A right angle is roughly three to four inches from the tip. The side of the right angle facing the tip is smooth and rounded; the opposite side has a saw tooth edge (photo 11). The entire hook is one piece from the tip to the handle. The shaft is covered with a rubber sleeve, which provides protection to a gloved hand in case of electrical contact. Once the point and right angle have penetrated the ceiling, you can rotate the handle 90 degrees. The right angle will grab an additional part of the ceiling as you pull the ceiling hook down and create a larger opening.

|

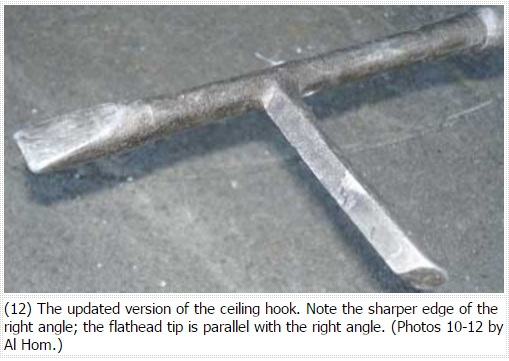

The second version of the ceiling hook is considered updated; yet, it is virtually the same design with minor modifications. The head is made of cast steel. The rounded side of the right angle is reshaped to form a sharper edge. Also, the flathead design of the tip is adjusted to be in-line with the extension (photo 12). The head is attached to a narrower yellow fiberglass shaft. The shaft is shorter; however, you can attach an extension pole at the handle. The newer version is lighter but not as durable. The lighter weight and narrower shaft also require more physical strength to push this hook through a ceiling. The hook is designed to penetrate the lath-and-plaster walls of older homes in San Francisco.

|

The ceiling hook is also a valuable tool to bring to the roof for vertical ventilation. In San Francisco, a firefighter with the ceiling hook and a second firefighter with a power saw can be assigned to the roof. Before stepping onto the roof, the first firefighter can use the hook to sound the roof. If the roof needs opening, the firefighter with the saw can cut an outline of the hole in the roof. Then the second firefighter can use the right angle of the ceiling hook to grab the edge of the cut and pull that portion of the roof back.

Remember, if you don’t see smoke, gases, or escaping heat once you pull open the cut, there may be a ceiling below. If that is the case, the firefighter can grab the ceiling hook by the shaft near the head and stick the hook handle into the hole numerous times to push the ceiling down. A series of holes in the ceiling will eventually cause a large section of ceiling to fall. Remember to use the hook handle to push down through the ceiling so the hook’s head doesn’t get tangled on any wiring, ductwork, or hidden obstructions.

Although we use the ceiling hook primarily to open walls and ceilings, the hook has additional value on the fireground. You can ventilate the building from the outside by using the ceiling hook to break windows (photo 13). In addition to the ceiling hook, other truck company tools include the ax, halligan, power saw, TIC, and rope.

|

Thanks to the following retired members of the San Francisco Fire Department for their assistance: Battalion Chief Ted Corporandy and Captain Tom Murray.

SNOHOMISH COUNTY MULTIPURPOSE HOOK AND TRASH RAKE

By Driver/Operator Chad Berg

In Snohomish County, Washington, we have specific tool and job assignments, dictated by the type of run and conditions on arrival. If vertical ventilation is not required, our responsibilities as the outside team become horizontal ventilation; placing ladders for access, egress, and rescue; and securing the utilities. The interior team normally carries a set of irons, a TIC, and a hydraulic forcible entry tool—all commonly used throughout the fire service.

As the driver/operator (D/O), I am assigned the hook. It is my choice, based on the structure and its construction, as to the type and size of hook used to complete outside operations. Normally, most firefighters here choose the multipurpose hook for these operations. The hook is similar to the halligan hook, with one main difference: The hook’s head is equally shaped on both sides of its business ends. The hook handle is solid fiberglass, with stainless-steel wear sleeves normally mounted at the tip and base of the hook. Most of our hooks are specified to have an aluminum cast “D” handle on their ends. The handle is also covered in a nonslip grip, but it often wears off after use and is replaced by braided hockey tape for a good, consistent, and durable grip. Our truck carries five-, six-, eight-, and 12-foot hooks (the latter is equipped with a utility shutoff on its end) (photo 14).

|

We find this hook to be superior over the regular pike pole not only for pulling open walls, ceilings, and exterior siding but also for use as a lever from either end to pull up trim and cedar/composite siding. For ease of operation and quick access, there are five-foot hooks mounted on the exterior of the cab behind the officer and D/O.

When we need to perform vertical ventilation, we choose the trash hook, also known as the rubbish hook or the L.A. rake. This hook was originally designed to drag and separate debris and material during overhaul. It has two six-inch parallel tines protruding out of its upside-down steel triangle head assembly. These tines can be longer or shorter. We’re currently evaluating shorter tines to see if they help more for interior overhaul (photo 15). These tines have conical points at their ends that should always be sharp. Typically, the hook is attached to a fiberglass six-foot handle with a cast “D” handle on the end. Truck firefighters are fond of this hook for their roof operations.

|

You can use the large hook head as a sounding tool while traversing the roof. You can also point it with its tines facing upward to sound the roof to find structural members and determine overall membrane integrity. The hook is very successful in removing roof sheathing or pull-backs. Place the tines directly into the cut section and pull back or into the relief/purchase point of the cut. When pulling up roof sheathing, you can also straddle the structural member with the hook head’s cross piece, with both tines under the roof sheathing and adjacent to the rafters. Next, instead of pulling the hook’s handle to remove the roofing, simply use the hook as a pry bar to release the sheathing. This method works well with tongue-and-groove sheathing. Remember when using “D” handle hooks to place your hand through the handle to ensure that you generate the full force of the tool and don’t experience slippage. Once you open the roof, push down the ceiling to ventilate the area. The head pushes down a large surface area. If the area does have a lot of ductwork or wiring, use the tool’s “D” handle to push the ceiling down (photo 16).

|

When performing roof operations on pitched roofs with a roof ladder, we use the trash hook for sure footing for a cutting and balancing technique for cutting holes in peaked roofs out from the ladder onto the roof. We slam the hook’s head into the roof material below the ventilation hole area. With six inches of steel anchored into the roof, you can feel confident that the hook will hold your body weight. By dropping only a single tine into the roof, you can change the angle of the hook to cut in other directions or areas. Although the hook is cumbersome for interior operations, when it comes to the roof, it’s irreplaceable.

LOS ANGELES PERSONAL AX AND RUBBISH HOOK

With Captain Steve Ruda

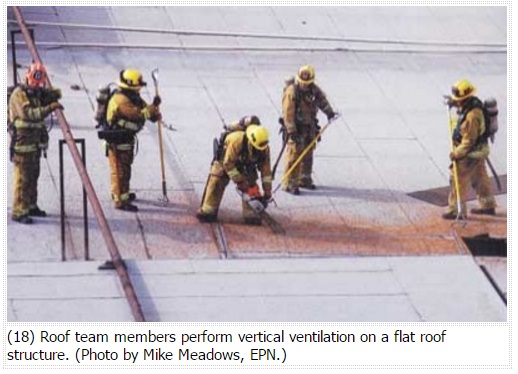

The Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD) operates 48 truck companies, each staffed with five firefighters. The trucks carry a variety of ladders (combination, straight, roof, and extension) and have a total of 420 feet in ground ladder inventory. As a truck company, all the members ladder the structure with either the aerial or ground ladders. In addition, they are assigned the following positions, duties, and tool assignments:

Apparatus operator: drives and operates the apparatus and then reports to the roof to perform vertical ventilation.

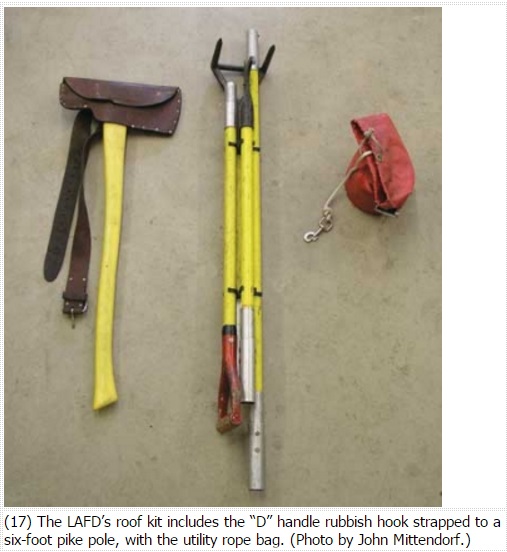

Top firefighter:takes the roof kit (“D”-handled rubbish hook strapped to a six-foot “D”-handled pike pole), chain saw, and utility rope bag to the roof.

Tiller firefighter:controls the utilities (gas, electric, and water) and then goes to the roof for fires in single-family dwellings or small apartment houses; at fires in high-rises or commercial occupancies, he reports to the roof, and the next-arriving ladder controls the utilities.

Inside firefighter: operates with the engine company with a set of forcible entry tools and the forcible entry saw if needed; he may carry a ram bar (like a slide hammer with a forked end), a hayward bar (claw bar—a fork at one end and a hook and two cully lugs, used to provide leverage with hard-to-open standpipe gate valves, at the other end), or a halligan.

Truck officer (captain): assumes the role of the incident commander when arriving prior to a battalion chief; assigns companies to fire attack, exposure protection, backup hoselines (fire attack and water supply), and salvage operations. Once he relinquishes command, he joins his truck company on the roof. There he is known as the Roof Division and supervises ventilation operations.

The two most commonly used truck company tools in the LAFD are the personal ax and the rubbish hook (photos 17, 18). Each member carries a six-pound pickhead ax on a belt around the waist in a leather protective case known as a scabbard. The scabbard’s main function is to provide protection to the firefighter from the sharp ax blade. It also frees up your hands to throw ladders and perform other functions. The scabbard is mounted on a swivel mount to the belt so you can move the ax out of the way to perform tasks.

|

|

We use the ax for cutting, prying, striking, and breaking windows. The pick end is also good for removing lath and plaster, roof sheathing, and shingles. The ax handles are made out of white ash and treated with boiled linseed oil to protect them. When prying with the ax, be sure to do it in line with the grain of the ax handle and ax head. This reduces the chances of putting side pressure on the handle itself, which can crack if the item you are prying is substantial. Some axes have fiberglass handles. To maintain the ax head, remove tar from the blade with kerosene or diesel fuel. Hand filing will make the blade sharper than a grinding wheel will. Then apply a light coat of oil to the blade to prevent rust. All truck company members are equipped with axes; some engine company members carry axes for entry or exit.

The second most common tool the LAFD uses is the rubbish hook. The hook has a fiberglass pole with a “D” handle at one end and a steel head assembly on the other. The head assembly has two sharp prongs attached to the end. The hook’s head shape enables firefighters to tear open roofing, pull back roofing material, pry up the roofing with leverage, and push down the ceilings of a burning structure. You can bang the head forcefully into the roof, sounding the roof for a viable path, for weakened areas, and to locate the roof joists.

TOLEDO PICKHEAD AX AND NEW YORKER PIKE POLE

By Firefighter Jamie Morelock

Working fires are just part of the daily routine for many of the Toledo, Ohio, fire companies, especially those in the inner-city neighborhoods that surround downtown. The private dwellings there make up the bulk of our “bread and butter” fires. Depending on the district, these dwellings range in size from 500 to as much as 5,000 square feet and from one to three stories. The dwellings share several commonalities, such as wood framing, balloon construction, and heavy lath and plaster. They practically sit on top of each other, creating a severe exposure problem. Another issue that Toledo firefighters face is that more than 10,000 of these homes are vacant and sealed in an effort to reduce vandalism and arson. Aggressive firefighting operations are a must to prevent the loss of several structures at nearly every working fire.

The standard tools for these “bread and butter” operations are the pickhead ax and pike pole. A few exceptions are first-due companies [who trade the ax for a pro bar (halligan)] and rapid intervention teams (who carry a set of “heavy” irons—an eight-pound maul married to a halligan). These two tools fit well into our operations. We carry both six- and eight-pound pickhead axes on our rigs. In general, most of our firefighters prefer the lighter six-pound ax for interior operations and the eight-pound ax for roof operations (photo 19).

|

We have found the ax to be the most effective and efficient tool for removing the half-inch-thick plywood that secures the doors and windows on the ground level of most vacant dwellings. The panels are held in place by three-inch-long decking screws and large washers, spaced 12 to 16 inches apart on the right and left sides. Removing these panels is a high priority to effect entry and egress as well as ventilation. We have tried several tools and techniques, but simply sinking the ax blade into the plywood just behind the washer, causing the screw head to shear off, is the quickest and easiest. Once you free a side, you can hinge open the panel, usually causing the other side to pull free.

Inside, while some firefighters are advancing hoselines or performing a primary search, others are going directly to work opening up the walls and ceilings to prevent vertical and horizontal fire spread. Using the side “face” of the ax to strike the plaster in several areas from shoulder level to the base of the wall loosens it from the lath. We then use the pick to rake the crumbling chunks of plaster and the lath strips from the studs. The pick also makes short work of removing the large wood moldings common in these structures. Drive the pick into one end of the molding piece; it will usually split, and then you can easily pull it free from the wall.

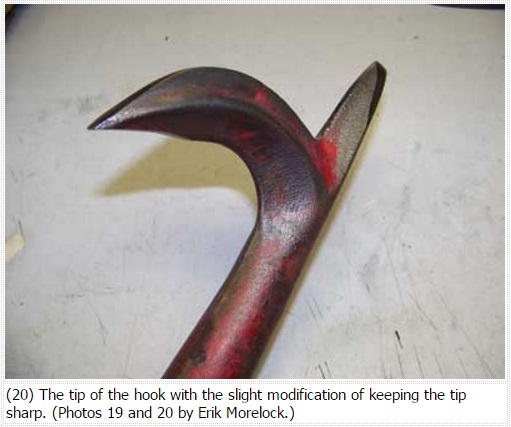

Our fire shop is responsible for the selection and distribution of all tools. When it comes to choosing a style of hook, the New Yorker pike pole is the standard. We carry a variety of pike pole lengths, but we most commonly use the six- and eight-foot poles. Compared with other pike poles, the New Yorker’s iron head is massive. Even with the extra head weight, the tool is well balanced and comfortable to use. The design and weight of this tool absolutely devastate heavy lath and plaster. Use the side of the head to loosen the plaster on the upper portion of the wall, then break several lath strips to create a hole at the top of the wall, and then rake the tool downward.

Once you open the walls, pull the ceiling by locating the wall on which the joist ends are attached to the studs, starting at the edge. It is much easier to start at the open edge than to try to create a hole to start from, especially when the plaster is reinforced with wire mesh. The New Yorker’s larger hook grabs more material than standard pike poles; two or three firefighters can strip an entire room of its coverings in a matter of minutes.

The chisel tip easily penetrates many types of building materials from bead board to soffit and light-gauge sheet metal when it is sharp. This slight modification of the hook makes removing wood trim and clapboards very easy (photo 20). Remove the trim by placing the hook against the wall above the trim board you want to remove, and slide the pike pole downward, driving the hook behind the board. Carefully pry outward to loosen it up and then pull it free. Remember, many times it is easier to start in a corner and work outward along the wall to remove the board.

|

To remove clapboards, drive the chisel underneath the bottom edge and pry outward to loosen the nails. Finish removing the first clapboard by nesting the bottom edge into the pike pole where the hook meets the chisel and pushing upward to snap the thin upper edge of the board. Remove subsequent clapboards by driving the hook downward behind the top edge and carefully prying outward to loosen the nails before pulling.

The pickhead ax and the pike pole may not be the first choice for many fire departments across the nation. However, they are some of the original tools of the fire service, and they have served Toledo firefighters well for more than 150 years. Remember, selecting the right tools for the fireground can make a difference in the efficiency with which we accomplish our tasks. Select your tools based on the knowledge of the districts to which you respond and your experiences operating there.

Of course, this is only a small sampling of the tools truck company members use across the country today. Many firefighters have made modifications to the tools mentioned above. And it’s not uncommon to find two separate hook heads mounted on opposite ends of the pole to provide more options. As you can see, all the tools mentioned above have distinct values to each of the fire departments that use them. Many of these tools have been around for decades, some with only minor upgrades, and they still help firefighters meet the increasing challenges of today’s fireground.

Michael N. Ciampo is teaching “Truck Company: Essentials” as an eight-hour evolution Monday and Tuesday, April 19-20, 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m., as well as the Big Room session “Truck Company Operations: A Hundred Things To Do” on Thursday, April 22, 10:30 a.m.-12:15 p.m., at FDIC 2010 in Indianapolis.

MICHAEL N. CIAMPO is a 24-year veteran of the fire service and a lieutenant in the Fire Department of New York. Previously, he served with the District of Columbia Fire Department. He has a bachelor’s degree in fire science from John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. He is the lead instructor for the FDIC Truck Essentials H.O.T. program. He wrote the Ladder chapter and co-authored the Ventilation chapter for Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II (Fire Engineering, 2009) and is featured in “Training Minutes” truck company videos on www.FireEngineering.com.

More Fire Engineering Issue Articles