You have likely heard the expression, “The fire service is 200 years of tradition unimpeded by progress.” Not only is this statement insulting to our predecessors, but it is also menacingly inaccurate. It is easy to get frustrated and disheartened by the deliberate pace of change in the fire service. Pausing to appreciate the progress we have made can be difficult because the next initiative is very alluring.

It is essential to acknowledge the innovations that have brought our service to where we are now. We have made tremendous progress in many aspects of our proud profession. The fire service has adapted to challenges and innovated through difficult issues. Our profession’s reputation for trustworthiness and courage is directly attributable to the men and women of decades past. We enjoy the benefits of a reputation that was established long before our first day on the job. Our predecessors laid a solid foundation that has allowed us to evolve into the all-hazards response service we are today. We have done this despite idle staffing models, plateaued budgets, and stagnant equipment. The fire service reviews new ideas thoroughly and thoughtfully.

(1) Two modern firefighters contemplate the delicate balance between tradition and innovation. (Photos by author.)

Perhaps we are slow to innovate because we fear change. Maybe we are deliberate in changing because it is imperative that the tools we employ work reliably to produce measurably better outcomes.

Employing contemporary technology effectively has consistently proven to produce measurably better outcomes in nearly every aspect of our society. When it comes to technology, the fire service has allowed its tradition of measured deliberation to impede our progression into the digital era. Introducing modern tech is not just a change for change’s sake; it is a vehicle for improving our service and capability. The meticulous pace of progress while exhaustively testing, debating, and reviewing potential options has found us behind the technology curve. The speed of technological innovation has outpaced our ability to implement readily available resources by more than a decade.

(2) You can use unmanned aerial vehicles to quickly assess conditions from previously impossible perspectives.

However, there are exceptions. Several forward-thinking fire departments have harnessed the power of modern technology to reduce response times, forecast resource allocation, increase firefighter safety, and improve services. These nimble departments have established an organizational structure and culture to remain near the leading edge of technology. However, most fire departments contain wide technological gaps that negatively impact preparedness, reputation, and operations.

The rate at which the fire service adopts and implements technology can, and should, be accelerated. Technological innovation provides a framework for a future in the U.S. fire service that is safer, more proactive, more agile, and more valuable to our communities. Modern technology has streamlined operations and improved functionality in nearly every aspect of contemporary society. Isn’t it time for the fire service to get up to speed?

(3) Technology, such as smartphones, can distract firefighters in many ways.

Can We Afford NOT to Do This?

There are significant challenges that impede our ability to adopt new technologies. To transition into the postdigital era of the U.S. fire service, we must recognize our technological shortfalls and identify practical solutions. Technology itself is not synonymous with innovation. In some ways, tech has created problems in modern society that have bled deeply into the fire service.

Advanced technology has diminished interpersonal relationships, devalued authentic communication, and often corrupted our attention. There are too many examples of firefighters misusing social media at the cost of their departments’ reputations and, sometimes, their own careers. The potential to overload people with information and complicate decision making is a valid concern. Like any transformative product, modern technology is not immune to being misapplied and misused.

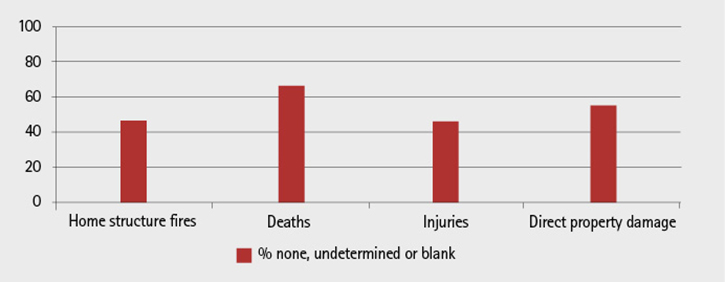

Figure 1. National Fire Protection Association: Ignition Factors in Home Structure Fires

Regardless of the year, the fire service has consistently been unable to gather meaningful, accurate data.

Source: NFPA Home Structure Fire Reports, 2013.

We point to limited budgets as a substantial challenge in implementing technology into our job. There are upfront costs to popular tech, but the long-range benefits far outweigh the initial expense. Additionally, low-cost options provide a pathway for budget-constrained organizations to usher in the digital age. Public service industries like law enforcement, emergency medical services (EMS), and the military have leveraged contemporary technology to create a force multiplier that bolsters efficiency and reduces operating costs. For example, the use of data collection and predictive analysis has shown to provide a tremendous return on investment. In 2015, the Los Angeles (CA) Police Department partnered with University of California—Los Angeles scholars to develop a crime prediction algorithm. As crime prevention and extra patrols are applied to the identified hot spots, the report1 showed a 7.4 percent reduction in crime in those areas. Researchers forecasted that the program would save the City of Los Angeles $9 million per year.

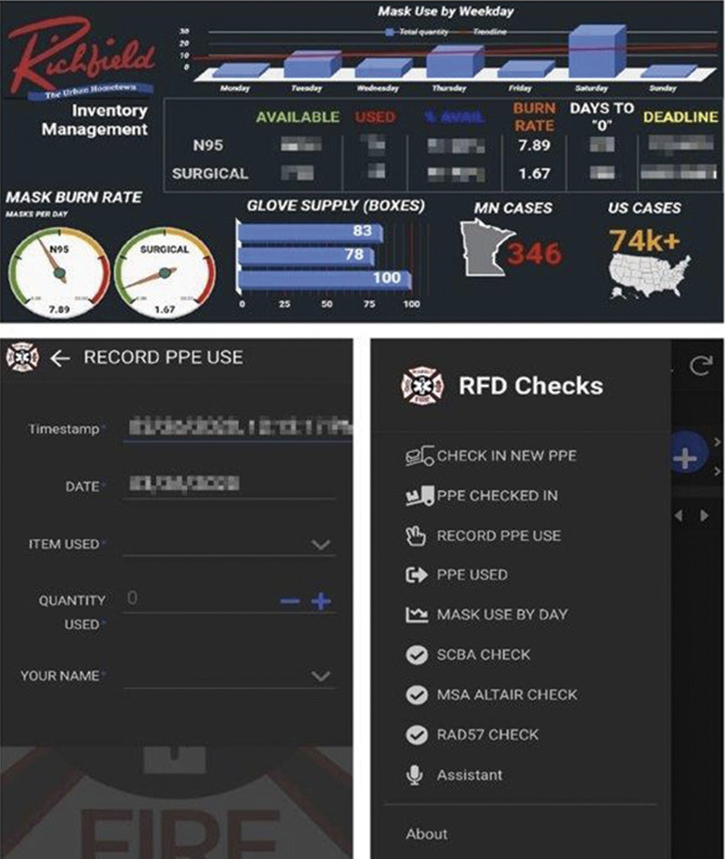

(4) During the COVID-19 pandemic, data is gathered by a mobile app to produce a real-time dashboard of PPE inventory, burn rate, and out-of-stock estimates.

A 2019 NASA study2 found that using real-time satellite imagery for routing emergency response during floods reduced response times by nearly nine minutes. A previous study3 from Thailand revealed that reducing every emergency response by one minute could save more than $50 million per year. According to the FCC,4 more than 10,000 lives could be saved annually by decreasing response times for fire/EMS by one minute. Clearly, faster response times produce better outcomes in law enforcement, EMS, and the fire service.

This application of modern technology aligns directly with our mission to save lives and property. Data-driven decisions for determining locations for fire stations and the positioning of our resources have a direct correlation to improved service and outcomes. According to National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) data,5 there were 3,655 civilian fire deaths in 2018. That same year, U.S. fire losses totaled more than $25 billion. If we could use technology to achieve a modest 10 percent decrease in these losses, we could prevent one fire death per day. When applying the annual monetary savings to the 1.15 million U.S. firefighters, that equates to roughly $2,174 per U.S. firefighter. What could your department do with an additional $2,174 per firefighter? The effective use of technology isn’t a line item; it is an investment that quickly matures into an invaluable asset for our communities. Since our primary mission is to save lives and property, we must ask: Can we afford NOT to do this?

Don’t Value Tradition Over Innovation

If we are honest with ourselves, the real challenge to implementing contemporary tech into the fire service is us. Our adherence to tradition and loyalty to our culture delay our ability to embrace new technology. There are nuanced layers to this issue, and the scope of this article isn’t a comprehensive examination of every obstacle. However, lack of competition and cultural values are universal challenges to technological implementation within our service. Uber and Lyft are always competing for customers. They have an incentive to use the most cutting-edge technology to create the best possible user experience. Therefore, Uber’s and Lyft’s sustainability requires an ongoing investment of resources dedicated solely to designing, testing, and implementing the most updated technology.

Corporations and commerce industries understand that a prime competitive advantage in the 21st century is their systems’ ability to collect, interpret, and act on data. Our “customer” doesn’t choose who will show up when he calls 911. There is no competing fire department fighting for market share or threatening to put us out of business. “The way we’ve always done it” mentality becomes acceptable and familiar. A competition vacuum allows tradition and culture to stifle progress. In the absence of real competitors, urgency and direction are generated by collaboratively working toward a clear vision by achieving SMART goals ahead of schedule and above expectations.6

Other public services also lack competitors. Why are law enforcement, EMS, and the military ahead of us in the tech race? These agencies have a culture of documentation that has provided them with a tremendously useful data set that they effectively use as the base for their decisions and to demonstrate their value. The fire service has historically been very imprecise and disorganized when it comes to collecting and interpreting pertinent data.

In addition to establishing a vision and goals, we need to enhance and sanitize data capture. The inconvenient fact is that our data does not even accurately depict the leading cause of fatal fires. According to the NFPA: “Code 5, the ‘Cause under investigation’ choice, allows fire departments to flag reports that need to be updated after the investigation is complete … the extent to which incident reports are not updated from Code 5 status is a major reason one of the leading causes of fire in the United States is ‘undetermined’ …. The total number of blank or unknown entries is often larger than some of the important subcategories. For example, 43 percent of fatal structure fires reported in 2007 do not have sufficient data recorded in NFIRS to determine fire cause. The lack of data, especially for these fatal fires, masks the true picture of the fire problem.”7

(5) There is no competing option for the services we provide to the public.

The United States Fire Administration adds, “This calculation, in effect, distributes the fires for which the cause data are unknown in the same proportion as the fires for which the causes are known, which may or may not be approximately right.”8 Without quality data, we cannot adequately translate our service’s value or our needs into terms that are meaningful to citizens and policymakers. The inability to accurately quantify issues severely limits the prospect of acquiring resources.

The merit of emotional and anecdotal pleas by our leaders for additional staffing and more money is nearly obsolete. We need to value data as an integral aspect of our duty and relevance. “Leaders drive values, values drive behavior, behavior drives culture, and culture drives performance. High performance makes new leaders.”9 We do not value data in our firehouses in part because its influence on decision makers outside our firehouse is not well understood. We are products of a culture that tends to overvalue instinct and tradition while undervaluing innovation and foresight.

(6) Modern firefighters should aim to develop full-spectrum skillsets, including technological proficiency.

(7) You can use the app ThingLink© to create densely informative, self-navigated, virtual tours of equipment.

Promoting Our Most Innovative and Progressive People

Technological competencies are prerequisites for hirings and promotions in almost every profession in modern society. If the “Firefighter” title is to remain among the most respected in the world, the fire service must increase the value placed on technological competencies in hiring and promotional decisions.

Historically, we have devalued high-tech skills in hiring and promotional decisions. A resulting workforce that struggles to adjust to the quickening pace of modernization is predictable. The paradox of entrenched fire service professionals bemoaning new hires who cannot operate a chain saw while being unable to operate a computer themselves is astounding. These new hires have potentially never needed to start a chain saw until they began doing the job. The young new hires from the “information age” who are coming into our service today possess a growth mindset. They can effortlessly access hundreds of resources to help them learn how to start, maintain, troubleshoot, and operate a chain saw. However, an entrenched fire service professional with no tech skills exhibits a fixed mindset by neglecting to learn another vital tool: the computer. The modern-day fire service needs fewer short-sighted, episodic “fixers” and more long-term, strategic “growers.”

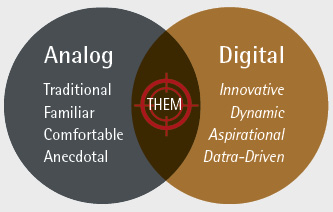

The disconnect between analog leadership and digital followers can create misperception and miscommunication in all phases of a department. Experiential and instinctual decisions clash with the expectations for evidence-based results. Training and operations get shaped anecdotally, not by science. Information filters down the chain of command; it does not flow transparently. Traditionally, the fire service has demanded leaders who possess experience, charisma, and technical mastery. Our sustained relevance will require adaptive leaders with innovative mindsets who empower experimentation.

Once an organization reframes the cost/benefit relationship of tech, adjusts cultural values toward innovation over tradition, and puts tech-friendly leaders in place, it is well prepared for the future. Leveraging data and technology to improve service and outcomes measurably will meet less resistance, but there will still be a need for a strategic plan to implement and normalize changes. The stakeholders will need to create a sense of urgency, form coalitions, create and communicate the vision, remove obstacles, benchmark progress, and refine and build on the idea. While working toward these goals, the pace of technological advancement will only increase, and options will expand.

The next decade will see the normalization of artificial intelligence, machine learning, autonomous vehicles, smart buildings in smart cities, the “Internet-of-things,” advanced biotelemetry, unmanned aircraft systems, robotics, and mixed reality. The fire service’s need to embrace modern technology will only increase with each passing day. Depending on your starting point, this transition takes time, and gaining support from leadership will be essential.

Be Realistic, Start Small

How can firefighters and company officers promote technological innovation in the fire service? Start by identifying a system or process in your department that does not contain cultural significance. Choose something antiquated and cumbersome. Maybe this is your truck checklist or a paper event calendar, a time-off request, or a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) log. Perhaps some old training on digital slides needs updating. Whatever your target may be, research tech platforms that streamline and simplify the process. Use your peer network to discover the methods others use. A paper truck checklist may benefit from using ThingLink to include some interactive images.

Figure 2. Analog vs. Digital

Progress requires a focus on the commonalities between ideologies. (Courtesy of author.)

An online calendar is also a great way to transform a paper calendar into a more accessible and useful tool. Recreate time-off requests and SCBA logs easily with Google Forms. Give new life and potency to digital slide presentations by converting them into Prezi or Nearpod presentations. Once you choose the platform for your project, work on planning, designing, analyzing, and refining the process within the new medium. Keep the digital version as close to the analog system as possible. Pick a few allies to beta-test your proof of concept, identify the most likely antagonists, and ask them to find flaws. Embrace their resistance and apply appropriate changes based on feedback from all sources. Be flexible, and compromise on anything that doesn’t diminish the value of the product. Be mindful that features do not always equal benefits. Simplicity in design and function is essential. Don’t allow yourself to get too emotionally attached to the project. According to a survey of 550 businesses, 68 percent of tech implementation projects will fail.10 If the project falters, refine or shelve it and move on to a different plan.

(8) Respecting tradition must include an appreciation for the fire service’s culture of diligent innovation. On the left is our modern firefighter. On the right is American fire service founder Benjamin Franklin as depicted in an 1850 painting by Charles Washington Wright.

Be Mindful of Tradition

There is a cherished place for tradition in the fire service, and we should revere its history. This respect for the past helps us appreciate the present. Our propensity for thoroughly vetting new ideas shields us from sales gimmicks and protects us from some dangerous tactics. We should also remember that innovation and progress are as deeply rooted in our culture as leather helmets and mustaches. Honoring our traditions includes building and renovating atop the footings our predecessors set. The elements of our past that continually strengthen our service must remain. “The way we’ve always done it” is appropriate as long as it remains the objectively most effective practice. If a measurably better method gets presented and we do not change, we are slandering our tradition of adaptability and innovation. We are a respected and an essential service today because we have evolved through the decades to meet the needs of those we serve.

Our community’s requirements and the complexities of our service continue to grow at an increasing rate. Modern technology is an undeniable option for many of the issues we face today and will face in the future; the challenge is how to harness its potential. Fortunately, we have a formula rooted in tradition to help us meet this challenge. We simply need to do it “the way we’ve always done it” by adapting and progressing right along with needs and expectations.

Firefighters are some of the most functionally intelligent, adaptable, and industrious people in the world. We appreciate the elegance of working smarter and harder. If new technology can truly make us better, we will eventually embrace it. When that happens, we will ask why it took so long, and we will start to seek ways to improve it. Change in the fire service is not always graceful. The flagbearers of progress are not particularly popular, but this innovative spirit is the heart and soul of the U.S. fire service. Take a moment to enjoy it, then get to work on the next tech project—we have a lot of catching up to do!

References

1. Mohler G, M Short, S Malinowski, et al. (February 2015). “Randomized Controlled Field Trials of Predictive Policing.” Journal of the American Statistical Association, vol. 110, no. 512, pp. 1399–1411. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1br4975j.

2. Blumberg S. (November 22, 2019). NASA Space Data Can Cut Disaster Response Times, Costs. Retrieved from NASA.gov: www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2019/nasa-space-data-can-cut-disaster-response-times-costs. Retrieved from https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2019/nasa-space-data-can-cut-disaster-response-times-costs.

3. Henrik J, L Prachaksvich, A Amornpetchsathaporn. (July 2014). “Time Is Money, But How Much? The Monetary Value of Response Time for Thai Ambulance Emergency Services.” International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 17(5), 555–560. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.05.006.

4. Serrie J. (December 28, 2018). Retrieved from https://www.foxnews.com/us/911-centers-struggle-to-find-callers-on-cellphones-and-results-can-be-deadly.

5. Everts B. (2018). Fire Loss in the United States in 2018. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association. Retrieved from https://www.nfpa.org/-/media/Files/News-and-Research/Fire-statistics-and-reports/US-Fire-Problem/osFireLoss.pdf.

6. Locke EA. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 3(2), 157–189. DOI:10.1016/0030-5073(68)90004-4. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0030507368900044.

7. Kinsey K. “Conquering the ‘Unknowns’: Research and Recommendations on the Chronic Problem of Undetermined and Missing Data in the Causal Factors Sections of the National Fire Incident Reporting System.” Retrieved from http://www.nfic.org/docs/NASFMFoundationFinalReportConqueringtheUnknowns.pdf.

8. USFA. Data Sources and National Estimates Methodology Overview for the U.S. Fire Administration’s Topical Fire Report Series (Volume 19). Retrieved from https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/statistics/data_sources_and_national_estimates_methodology_vol19.pdf.

9. Zwilling M. (May 20, 2012). “6 Key Attributes of a Winning Business Culture.” Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/6-key-attributes-of-a-winning-business-culture-2012-5.

10. IAG Consulting. (2009). IAG Biz. Retrieved from https://www.iag.biz/resource/business-analysis-benchmark-full-report.

SHEA CHWIALKOWSKI is a 12-year fire service veteran and a firefighter for the Richfield (MN) Fire Department. He has also served as training captain for the Minnetonka (MN) Fire Department. Chwialkowski is a member of the Underwriters Laboratories Firefighter Safety Research Institute Coordinated Fire Attack advisory panel. Chwialkowski graduated from the National Fire Academy’s Managing Officer program and was the education trustee for the Northland F.O.O.L.S. He participated in the Brass Tacks, Hard Facts video training series and contributed to the textbooks Foundations of Instructional Delivery: Fire and Emergency Services Instructor I and Fire and Emergency Services Instructor. Chwialkowski is also the lead instructor for the Southwest Metro Recruit Academy in the Twin Cities.