By James Silvernail

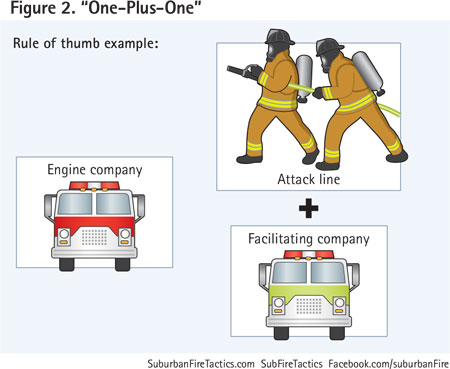

The “One-Plus-One” concept is a tool for developing functional standard operating guidelines (SOGs). It assists with accounting for truck company functions on a fireground when there are no truck companies to dedicate to this task. It facilitates the effective placement of handlines by coordinating all essential functions associated with deployment. It strongly emphasizes the concept of “First line first.”

|

| (1) The common response apparatus in an operation that uses a “functional” standard operating guideline can consist of quint apparatus and engines. This response requires a game plan for coordination to ensure effective prioritization and accountability of essential fireground functions. One tool for creating these guidelines is the “One-Plus-One” concept. (Photo by Battalion Chief Mike Digman, Metro West Fire Protection District, St. Louis County, Missouri.) |

For many of us in suburban and rural America, going to fires with an apparatus without a pump, hose, or water is not reality. Truck companies are mostly nonexistent. Does this mean that we do not have truck company functions on our firegrounds? Does this mean that we cannot perform a coordinated fire attack? Absolutely not! However, we rely on a system predicated on functional SOGs. This is in contrast to a positional system that uses apparatus, trucks (ladders), and engines that have specific duties on the fireground.

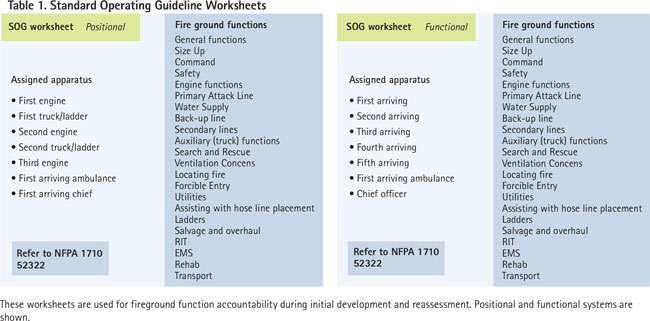

Contrasting Functional and Positional SOGs Positional

In a traditional positional system, engines and trucks (ladders) are assigned to first-alarm or box assignments. In larger urban settings, this assignment may also include heavy rescues and squad companies. An example of a typical response may be the “3 and 2.” In this response, there are three engines and two ladders with the possibility of a special unit, such as a rescue or squad company. Depending on the agency’s SOG, typically the first-due (arriving) engine initiates fire attack by deploying a hand-line or a fire stream. The second-due engine assumes a backup or secondary line, and the third-due engine may assume any engine function that is needed or may not have yet been performed. The first- or second-arriving engine usually secures the water supply, depending on the agency’s preference, circumstance, and type of hoselay (forward or reverse lay). In other examples of this structure, the first-due engine still commits to fire attack, the second-due secures the water supply, and the third-due deploys a backup or secondary handline.

The truck companies assume their associated duties, most commonly associated with the “LOVERS U” acronym for truck company operations: Laddering, Overhaul, Ventilation, forcible Entry, Rescue, Search (for fire and occupants), and Utility control. In the “3 and 2” response plan, typically the first-due (arriving) truck company assumes all associated fire floor activities that will facilitate the handline placement, fire floor search, and rescue procedures. The second-due truck will then complete all truck functions not completed by the first-due or assume “above” fire floor activities. When heavy rescue companies are available, they generally assume truck company operations. Often, additional truck companies will assume the role of the rapid intervention crew; however, this is not an absolute and that task can be assigned to engines.

Functional

As stated earlier, the major difference between positional and functional SOGs is the lack of dedicated truck companies. In reference to truck or ladder companies, the term does not refer to the apparatus but to crews. For example, an apparatus that has an aerial device is expected to operate as an engine company because of its ability to deploy lines and pump water; however, it may not be considered a truck company. Traditionally in a functional system, these types of apparatus, more commonly known as quint fire apparatus, are relied on to operate as an engine company. Often, this is determined by arrival order. In this instance, they are not considered dedicated truck companies. Also, if a ladder company is staffed with one or two personnel, can it be considered a truck company? The answer should be no. The apparatus can operate its aerial and position to gain access to upper floors; however, the crew cannot assume essential interior operations associated with truck company functions.

Therefore, we arrive at the big question: “Who does the truck work?” Before we analyze the question, let’s discuss a typical example of a functional response. A functional SOG may or may not have a truck company assigned. Doesn’t that mean that if there is a truck company, it is a positional system? Not always. Remember, the key phrase is lack of adequate truck companies. One truck company cannot typically accommodate all truck company functions at a structure fire. Also, many truck functions must be initially implemented early in the prioritization of fireground functions for successful line placement and victim removal/rescue. If the truck is late in the arrival order, we cannot wait for it. Other companies will assume truck operations even if they possess hose and pumps. An example is the St. Louis (MO) Fire Department, which details one hook and ladder (truck company) per battalion. Early-arriving companies, quints, or possible engines will either initiate truck functions prior to the arrival of the hook and ladder or supplement truck company operations.

|

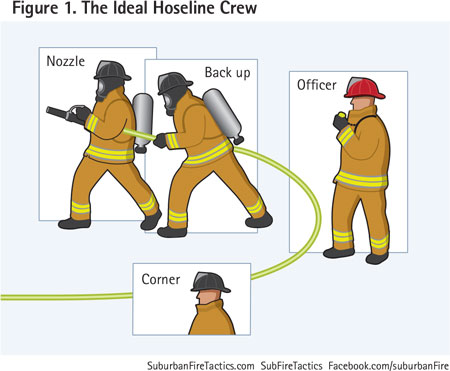

| The ideal hose crew consists of the nozzle firefighter, officer, backup firefighter, and corner (control) firefighter. |

An example of a common functional SOG response may include five to six apparatus. This is determined by resource availability, staffing, and agency capability. It is important to note that the description of the company is specific to the crew, not the apparatus. All functional assignments dictated in the SOG are for the crew, not the apparatus. For example, a quint apparatus may arrive first on the fireground and be expected to initiate an immediate interior attack (very common). Does that mean the apparatus “flipped a coin” and decided it was an engine and not a ladder? Absolutely not. The crew fulfills the function of an engine company and deploys a line; however, the apparatus will still be expected to position the aerial and raise to upper floors. In a vice-versa example, a quint may be second due and expected to initiate immediate fire floor truck company operations. Unfortunately, in a system that operates with quint fire apparatus, it is not always ideal to reverse-lay out for logistical considerations. In this instance, the second due may be expected to straight lay in from the hydrant to secure a water supply. Therefore, the crew is expected to operate as a truck company, but the apparatus is satisfying an engine company function. The designation on the SOG will not denote engines or truck/ladders assigned; they will be designated by position “arriving” (Table 1, left side).

In a functional SOG ( Table 1, right side), how do you decide which companies will be performing functions associated with engine company operations and which will be performing functions associated with truck company operations? First, the point must be made that SOGs must be agency specific and developed for your specific agency capability and circumstances. Examples of these factors include staffing, available resources, and response area characteristics. Second, SOG assignments are based on an understanding of critical fireground principles, prioritizing fireground functions that impact the outcomes of the fireground, and directly linking strategies and tactics to fireground objectives. The bottom line is always that firefighting objectives and priorities are to save lives, protect/conserve property, and minimize harmful impacts on the environment.

Critical Fireground Principles and Prioritizing Functions

In the March 2011 issue of Fire Engineering, my first article on the topic, “Suburban Fire Tactics: Prioritizing Functions and Developing Preferred Operating Methods,” was published. The theme was, as it is today, operational guidelines beginning with prioritizing fireground functions. We begin by realizing objectives and identifying prioritized strategies. Strategies and objectives do not differ for fire service agencies across the globe and remain constant. Fireground strategies will always include fire location (remember, search includes locating not only entrapped victims but also the fire and noting its progression), contain/confine, and extinguish.

A common question is, Under which strategy does rescue fall? The answer is, it should be accomplished immediately or as soon as it can be effected. Rescue should be immediate; however, in many circumstances, it cannot be initiated until we locate the fire and entrapped victims and contain/confine the fire from the victim or gain access or egress to the entrapped. In many instances, rescue does not look like the rescue chapter in the typical “recruit” book. Often, it involves a handline. However, look at the example of the occupant hanging out of a window with heavy smoke billowing out overhead and fire quickly impending. The victim has been located immediately, and the fire has initially been located. Do we dare wait to contain/confine before we throw a ladder? NO. The point of the example is, no fire is the same, and many different circumstances are possible. The rescue strategy does not fall within strategy priorities; it must be considered immediately. Rescue remains our highest priority.

|

| Illustrated here is the underlying concept of “One-Plus-One.” Each attack line should have a facilitating company (truck work) with the appropriate forcible entry tools to allow the hose crew to concentrate primarily on positioning the attack line. |

The largest impact we can make on the fireground is to put out the fire and remove the hazard. We understand fire service objectives and the strategies undertaken to achieve these strategies. But how do we achieve strategy? The answer is tactics. Tactical implementation is the physical act of placing fireground functions on the fireground. This is the critical component in the matrix that makes agencies different. Agency capabilities, resources, and staffing will cause tactics to differ from agency to agency. How handlines are placed in suburban America differs from how it is done in urban and rural America. It may also differ among suburban agencies, depending on the staffing and resource availability. For example, compare the difference between a three- and five-person engine company. The three-person engine company requires a greater facilitation effort to get the line in place. Therefore, later-arriving companies supporting the three-person engine may be detailed more assignments associated with first line placement as opposed to the immediate deployment of a second handline (Table 1, right side).

The main underlying theme when considering tactical implementation of an SOG resonates with the following: “No other action taken on the fireground saves more lives than the proper size attack line, stretched to the correct location, and placed into service at the proper time.” The SOG should support the critical three points of this statement-the three Rs: right size, right place, and right time. Without a doubt, the right time is always as soon as possible. Developing a game plan to support this will foster consistent, safe, effective, and efficient operations.

The “One-Plus-One” Concept

The physical action of placing a handline into service requires more than simply stretching and placing a handline at the seat of a fire. Often, facilitating actions must occur simultaneously for the three Rs of effective hoseline placement. It is what is commonly referred to as the coordinated fire attack. Let’s look at an example.

It is three o’clock in the morning, and you arrive first due at a reported fire on the third floor of a garden-style apartment, wood-frame structure. The hydrant is at the corner, approximately 200 feet before the complex. There are six units (apartments) in the structure, which has a center core hallway. On arrival as the first-due officer, you report a moderate smoke condition at the eaves of the third floor from the unit to the left of the stairwell. Go!

|

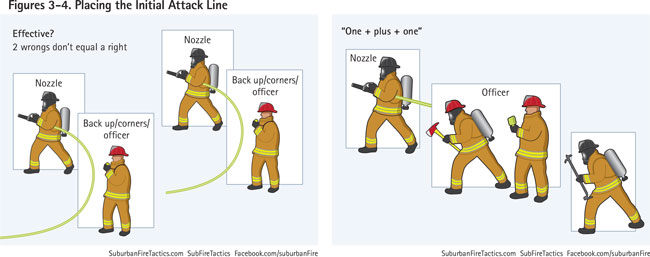

| The importance of coordination is illustrated. Concentrate on placing the initial attack line as opposed to understaffing two simultaneous lines and not accounting for associated facilitating actions. |

What must be considered when determining the initial actions of this scenario? Numerous actions must take place to successfully place the right hose in the right position at the right time:

- The officer must conduct a 360° walk-around to gain situational awareness, identify circumstances, and begin fire and possibly victim location.

- The adequate size hoseline (in diameter and length) must be stretched up two stories to the third floor.

- The door may need forcible entry.

- The fire must be located, as well as possible victims. (What if the fire is caused by a wire or light fixture in the overhead ceiling space? Knowing the room of origin does not mean you have located the fire.)

- Extinguish the fire.

- Be ready for forcible egress in the case of collapse or rapid fire spread.

- Secure a permanent/fixed water supply.

Here is one more challenge. Your engine company has only three personnel: a driver/engineer, an officer, and a firefighter. How do you implement all of these functions and extinguish the fire? The answer is, you can’t do it by yourself. Develop an SOG and a game plan that consistently support implementation of prioritized fireground functions.

The “One-Plus-One” concept acknowledges the fact that all essential fireground functions needed to place a hand-line cannot be accomplished by a single company, especially when the company is short staffed (Figure 2). It also acknowledges that truck company operations must be accounted for on every structure fire regardless of whether your apparatus is equipped with a hose, a pump, and water. The concept is simple: Each attack or handline must have an accompanying company assigned to facilitate the placement of the handline. Therefore, out of the five or six assigned apparatus (which all may have engine capabilities), you can begin identifying assigned facilitators (a suburban fancy name for a truck company). This places emphasis on getting the first line in service before complicating the situation by trying to place secondary lines with substandard staffing and no facilitating actions.

|

| This table simplifies and categorizes the fireground functions and assigns them to “arriving” companies in a functional system. The difference between these examples is agency capability at the single resource level. |

Without a game plan, most companies that arrive with engine company capabilities feel obligated to commit to engine work. Let’s revisit the example of the garden-style apartment fire. What happens if the second-due apparatus elects to pull a secondary or backup line? Will essential functions be missed? Absolutely (Figure 3). In the “One-Plus-One” model, the second crew will report with hand tools [at least a set of irons, a hook, and a thermal imaging camera (TIC)] and begin assisting the first line. Now, the first-due company will have assistance with above-grade stretch, forcing the door (irons firefighter), locating the fire and possible victims (hook to get into the ceiling and the TIC to observe for heat signatures), and tools for forcible egress in the case of an emergency. The third-due or later-arriving companies will then deploy the backup or secondary lines (Figure 4).

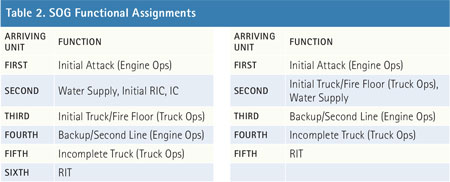

Using this concept with functional SOG development, example response assignments might look similar to Table 2.

Keep in mind that these are examples of functional SOGs. They might not be perfectly ideal for your organization, depending on your circumstances or capabilities. The main point is that all essential fireground functions should be accounted for to support consistent, safe, effective, and efficient operations. The main action and power statement behind this is, “No other action taken on the fireground saves more lives than the proper size attack line stretched to the correct location and placed into service at the proper time.”

JAMES SILVERNAIL has been a member of the fire service for more than 18 years. He is a battalion chief with the Metro West Fire Protection District in St. Louis County, Missouri, and is internationally accredited as a Chief Fire Officer. He is the author of Suburban Fire Tactics (Fire Engineering, 2013). He is a lead instructor at the St. Louis County Fire Academy, specializing in truck company operations, and a planning team manager for MO-TF1. He has an AAS degree in fire protection technology, a BA degree in business administration, and an MS degree in human resource management. He has written numerous articles for Fire Engineering and is an FDIC workshop instructor. He is a principal member of National Fire Protection Association technical committee for 1710 and is a western regional director of the International Society of Fire Service Instructors.

James Silvernail will present “Fireground Decision Making for Suburban Company Officers” on Tuesday, April 19, 8:00 a.m.-12:00 p.m., at FDIC International 2016 in Indianapolis.

Suburban Fire Tactics: Prioritizing Functions and Developing Preferred Operating Methods

Suburban Firefighters: Ready or Not, You Will Be Called First

Suburban Firefighting: Tactics, Strategies, and Critical Concepts

Fire Engineering Archives