There are many unfortunate instances where firefighters are forced to use the inherently untrustworthy fire escape for either access or advance. From down live wires blocking interior access to a stalled-out attack because of interior conditions or a partial collapse to destroyed stairs and the like. There are also just as many reasons not to use a fire escape to establish access to a fire—namely, we have no control over the state they are in, they are easily overloaded, they are a tough climb and an even more cumbersome haul, and they are a “dangling confined space.”

- Positioning Portable Ladders for Work on Fire Escapes

- Training Minutes: Overcrowding on Fire Escapes

- Training Minutes: Fire Escapes

Much has been written regarding the damaged or destroyed conditions of our fire escapes, their special hazards, and their unreliable nature, but there is one simple reason you would not select even a pristine fire escape for primary access: It provides absolutely no protection to the interior egress route by doing so. In any case, if forced into a fire escape hose advance, there are a few safeguards and tactics you can employ to increase your chances for speed; mobility; and, ultimately, success.

Look Up!

Chances are that if your company is arriving and will have to attempt a fire escape advance, that call has been made by an earlier-arriving company. For example, an interior line may have made it through the door just as live wires came down behind it (unbeknownst to me, this happened to my company). In this instance, you may be arriving to the first-in officer or first-arriving chief transmitting that the second line needs to find another way in (along with an additional alarm). If the fire escape is the method of choice, the first thing to do is look up at it; I do not refer here to the assessment of the condition. If the escape is rusted, rotten, and falling apart, assume it will not be chosen. However, this decision will be based more so on the tactile factors that will slow down and hurt your ascent. For instance, are there air-conditioners (ACs) jutting out of the windows and blocking your pathway on the escape? Are there furniture, planters, bicycles, and garbage on the landing? In the summer months, you may also encounter makeshift patios on them. As problematic as blockages are on a regular stair, they are compounded by the narrow nature and small landings of a fire escape.

You must quickly determine whether the escape is workable. For example, in the middle of a February night, the counterbalance weights can be frozen to their bases in blocks of ice. The holding hooks on the drop ladders can be similarly frozen. Can you free them quickly by safely knocking the ice off with a hook, or are they encased? In this case, if you cannot pull down the drop ladder, you need to anticipate that a straight ladder may be needed to establish access to the first landing. Know that you cannot yank violently at a frozen or stuck drop ladder (photos 1, 2). Similarly, on a cold night, expect that the metal treads, rails, and landings will be incredibly slippery and can almost negate a speedy ascent and haul. The added loading of ice on an already old escape is a well-known consideration that needs a quick look.

(1) Photos by author.

(2)

Also in the realm of a “workable” fire escape is people. Unlike advancing up an interior stair while victims flee, trying to ascend a narrow fire escape while victims are descending presents both overloading and logistical problems. Stairs are generally wide enough for just one person, and spaces on landings behind the stairs are barely wide enough for one firefighter. Victims descending thwart a fire escape advance—at least until they are down.

Additionally, if in the middle of a hose haul up an escape, firefighters need to look up prior to opening the windows to get in. If victims above have gone onto the fire escape for any reason, from refuge to curiosity, they can be engulfed by smoke as you attempt to make entry. The victims must be removed off the escape or sheltered in place in their apartment prior to the advance.

The Haul

There are many methods for hauling hoselines up ladders and escapes and from windows. For our purposes on the fire escape, the method of the actual haul is not nearly as important as taking the time to establish how it will be successful. This is done by having what you need prior to ascending. An engine company with an officer and two firefighters to assist, advancing from the apparatus bed, can make critical decisions at the base of the escape to ensure success. The equipment generally required is a utility rope bag with a “Figure 8” knot and a carabiner affixed to it. Note: If the bag has a pocket in it, keep an additional clip/carabiner inside. This can serve to secure the rope for the haul or for the hose later in the operation.

Also needed is a means to get into and clear windows; a set of irons works fine here. The member with the rope bag needs to ascend quickly to the required floor and, while taking care not to lean on the outer railing, throw the bag out and away from the fire escape (photo 3). I have seen the bag hit a lower landing and fall back into the fire escape. Do not lower the end of the line with the carabiner, as this method is slower. Additionally, the loose line can be blown all over the place and back into the fire escape.

(3)

You can also clip the end of the rope with the carabiner to the fire escape itself. However, if you are hauling a charged line, it may not be good to have all that extra weight pulling against a railing or stair of the fire escape. It would be better to reach inside the window and clip it to a radiator or something substantial. Also, refrain from clipping the end of the utility line to yourself.

The member at street level needs to fold the uncharged line “accordion” style (folded at about the length of a high-rise pack) and secure the utility line at the midpoint of the hose. It is sound practice to look up and ensure that the folds can make the ascent unimpeded. There may be times when trees or other obstructions make the haul so narrow that even an uncharged line is hauled solely by the nozzle. That said, there are many ways to tie the folded line; the “go-though” loop is the simplest, fastest way and generally the best. This fold is a simple half-hitch, where you “reach through” and pull in a bight (photos 4, 5).

(4)

(5)

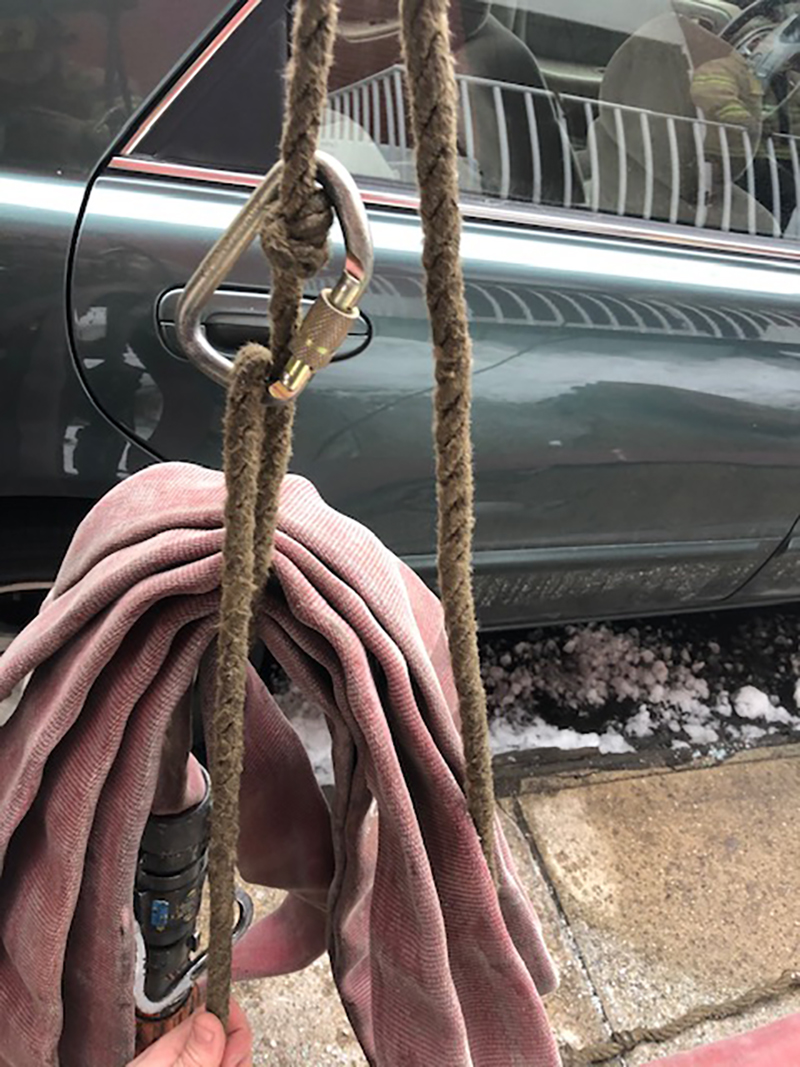

Shoddy utility ropes are also an issue. These lines get beat up and are not subject to the same kind of inspection as life rope. The fire scene is not a place to struggle with a ratty, knotted, or partially frozen rope. If a difficult rope cannot be tied immediately, it can be secured easily with two wraps around the folds and an extra clip (photo 6). In this instance, be sure the clip is snugged against the hose. Ensure that the wraps and clip will not slide off the hose in the ensuing haul. Remember, when tying and hauling equipment, life safety knots are not required. Do not be careless, but make sure the rope is secure and can be undone easily at the end of the haul.

(6)

Also, do not spend more than a few seconds to tie the haul line to the hose or nozzle. The officer should be ascending with the hauling firefighter to assist and establish access. A charged line can be hauled by securing the bail with a clip or a tieback behind the nozzle. Whichever method you employ, remember that, with the nozzle facing upward, should the bail be pulled against anything, the nozzle will open and flow and create a real problem. Should you tie the line behind the nozzle with the bail unsecured, this is a real possibility (photo 7). By hauling from the bail, the nozzle reaction against an open bail will almost instantly close it—problem solved. Follow your department’s general orders on specific methods for tying and hauling equipment. I stress only that it should be clean and quick.

(7)

The Advance

There is some discussion regarding which floor to haul from. Just as you would ascend to the next landing of an occupied multiple dwelling to make a smoother advance of the line down into a fire apartment, so too should the haul from the fire escape proceed if it can be done safely and protected and certain conditions are met. If you are advancing the primary line to the fire from the fire escape, you cannot do this. If the first line onto the fire floor will be from the fire escape, advance it from the floor below; charge the interior; and then up to the fire, if possible. This provides some measure of stairwell protection. Remember, just because your company is advancing from an escape does not mean that your interior throat protection hazard has been abated. Companies should also remember that interior stairwell protection is paramount, regardless from where the line is stretched, especially if it’s the first or second line.

Next, always maximize the egress and the ladder crew’s protection while getting to the seat quickly. If the advance from the fire escape on the fire floor was borne out of a destroyed inside stair, a renovation, or ongoing construction with entire sets of stairs missing, you obviously cannot advance and charge from underneath as stated. In this case, the hauling member needs to get to the landing above the advance [in full personal protective equipment and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA)] and feed the charged line down into the window for the remaining members to advance inside. When possible, haul from the most advantageous position; you can always pull from the floor you will enter on and feed the line up a stair and back down. If the seat of the fire is, in fact, close to the point of entry, the fire escape landing above the access window will likely mirror the situation a firefighter faces at the top of a basement stair. Unlike an interior stair, the fire escape stair is so narrow that it may require a “vertical bend” to push downward onto the landing. Once this is achieved and the line is fed inward, that member can assist inside (photo 8). As stated, if it is punishing to feed the line from the landing above, the firefighter feeding the charged line into the window can do so from the landing of entry by pushing the line up the landing stair and having it come back down to him and into the window.

(8)

When possible, limit flaking of the line on the escape; it is narrow, small, and primed for kinks. The line can also be pinched in between balusters on charging—if the folds are brought up uncharged, it can be done safely, so finish the haul from the entry point and flake out the line on the interior. It is a fair trade-off to terminate the haul inside and then charge or attempt to charge and flake everything out on the escape, especially if the entry can be isolated as follows. I am careful to use the word “advance” from the fire escape because “attacking” from the fire escape is not an option. Operating a line into a fire from the escape, even if you are going to crawl in to mop up, will punish victims, search crews, interior ventilation efforts, and the whole attack. We attack from the inside in the same manner that we would normally do so. We would not recklessly shoot water into a first-floor living room window and then go into the window to finish. Likewise, we cannot afford to make this mistake from a fire escape. You cannot advance from an escape that is at or near “light up.” Whenever feasible, your team needs to get under it or inside and to the seat quickly.

Communications with an interior crew can also pay big dividends. The crew may be able to isolate the fire on their end. As such, a quick hit from the escape, if needed, will not unduly endanger the attack. Barring a perfect estimate of interior conditions and the time it will take to haul, isolation of the advance is crucial. If your team is already in the unfortunate position of having to haul and advance from the escape, make every effort to isolate the initial advance onto the interior to ensure that you can complete the attack.

For example, if there is a good smoke condition at the window for your advance, you are likely adjacent to or near the fire area, and the officer needs to get into the window and close the door to isolate that area from the fire while the haul up the escape is taking place. In the same way we would vent-enter-isolate-search, if our team is entering the fire escape window near the seat, we need to stop our entrance point from becoming involved while we prepare to enter. This is perhaps the most important safeguard you can take for your fire escape advance.

Additionally, if lines are operating elsewhere in the building, they can “push” conditions into your entrance path without your knowledge. Opposing hoselines are not the issue here; it is a matter of the atmosphere taking the path of least resistance out of the building. That path can be in your team’s face, so isolate.

Extra Efforts

There are a few extra steps we can take to increase the chances of a successful advance from a fire escape. For example, the live loads mentioned earlier (with the exception of AC units) should be cleared by being pushed back into the windows rather than pushed to the side of a fire escape. You should take a hauled line “under” the rail of the landing that will be used not because the weight of a line will cause a rail break and subsequent landing break but because it will discourage members from excessively leaning on the rail to pull up the line and push it inward. Similarly, when securing the line to an escape (the line has made the seat, and the haul and advance are complete), secure it to the tread of the landing if a strap will fit through the gap. Better still, use a strap to secure it to the anchoring bracket underneath. Recall that fire escapes are merely cantilevered to the sides of buildings and strongest at the connection. The best option is to secure the line inside the building and not to the escape. Secure it to a radiator pipe or strap it to an exposed stud in an overhauled wall—anything solid and sturdy.

It is likely that you will be dealing with broken glass on both the fire escape’s and bedroom’s side of the advance. There is no way around it; slipping—not cutting—is an overlooked hazard. Nearly invisible broken glass on a metal escape is another real slip hazard. It is vital to stay off your hands and knees and, even more important, to not let your SCBA mask drag along the escape. Glass on the escape side at window entry should be cleared fully (or as close as achievable) before advancing both the team and the hoseline inside. If the window has not failed and can be taken without breaking, do so. If something from the bedroom can be laid over the windowsill quickly to ease the advance, considered doing so, so long as it does not take away from the attack effort or substantially reduce the profile of the window.

Also, be wary of removing SCBA partially or fully. In tight areas of fire escapes, it is sometimes necessary to reduce your profile to maneuver. If this is needed to get yourself into a position to advance, ensure that your team recalls the old adage, “left life,” and never fully removes or leaves their SCBA on the escape. Unlike the interior, where you duck back into a room to adjust your SCBA, there is nowhere to go or escape a bad condition on a fire escape. You would have to go directly up or down, and you need air to do this.

Additionally, if the haul and advance appear to be of considerable height and strain, seriously consider having two companies team up to complete the stretch. Having an additional engine company assist to stretch in, around bends, and up the stairs will make the task much easier. Unfortunately, this is not always an option.

Calling an advance from a fire escape an “imperfect” condition would be putting it nicely. It is a circumstance that can be set for failure before it even begins. Should it be attempted, it is best achieved through recognizing conditions and correct entry location, limiting personnel on the escape, speed, securing hoseline, and other safeguards.

ALEXANDER DEGNAN is an 18-year member of the Jersey City (NJ) Fire Department (JCFD), where he is the captain of #618 Squad Co. 4, a position he has held since 2015. Prior to his captain’s position, he was a 10-year firefighter with the JCFD’s #1013 Squad Co. 4.