Codes and emergency firefighter communications

I read with great interest the article by Chief Brian Crimmins of the Hoboken (NJ) Fire Department (“High-Rise Radio Coverage Improved Through Mandated Technology,” Fire Engineering, October 2019) regarding the implementation of the Fire Fighter Emergency Communication System requirements. I applaud the proactive efforts by the department to find solutions to the difficult and life-threatening emergency communications. I also applaud the chief and his team’s efforts on using the requirements in the codes to accomplish this initiative.

I could not help but think that this article may also provide a teaching moment on the importance of the fire service’s participation in the code process. We have to remember that if we want to improve the work environment of our firefighters, we have to participate in the processes that establish how this work environment will be designed, built, and maintained. These processes are our codes and standards managed by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) or the International Code Council (ICC).

The requirement for emergency responder radio coverage was not always in our codes. In fact, it first was adopted into the International Building and Fire Codes (IBC and IFC) in the 2009 editions. This was the result of a code change propagated by the ICC Terrorism Task Force Ad Hoc Committee led by Gary Lewis, a Summit (NJ) construction official. This Ad Hoc Committee studied the World Trade Center Collapse report authored by the National Institute of Standards and Technology; the author code change proposals were based on the findings and recommendations of the report.

Because of the difficulties in communicating during the response to the terror attacks, the report recommended requiring buildings to support the fire service communications throughout the building. This, in my mind, was one of the most crucial code changes proposed. Every single one of us in the fire service can discuss the difficulties we have experienced with our radios working in many of the buildings in our response districts.

Just because a national code change is proposed does not mean it is supported or will be adopted at the state and local levels; that is true with this proposal. At first, there was a strong reluctance for the adoption of this requirement because of the cost and difficulties in the requirements for building owners and managers. The fire service, led by representatives of the International Association of Fire Fighters, International Association of Fire Chiefs, National Association of State Fire Marshals, National Volunteer Fire Council, and additional representatives, lobbied hard and engaged representatives across the spectrum to discuss the importance of this requirement.

The resulting discussions and support from the American Institute of Architects, Building Owners and Managers Association, and others led to the adoption of the requirement of the Emergency Responder Communication Systems in the IBC for new buildings—but also, and maybe more importantly, adoption into the IFC. This means these requirements can be retroactively required.

In 2018, New Jersey adopted the IFC (2015 edition) not in whole. However, on the national level, IFC 510.2 permits the retroactive requirement of Emergency Responder Communications Systems as outlined by Chapter 11, which is based on performance and a few exceptions. The State of New Jersey deleted all of Chapter 11 “Construction Requirements for Existing Buildings,” which hindered the original language permitting building owners 18 months to comply; it was subsequently modified to allow a time frame established by the adopting authority.

Since New Jersey did not adopt this language, this is another lesson on why the fire service needs to be involved in the development of the codes at the national level in both the ICC and the NFPA but also at the state and local levels to ensure that the minimum safety requirements of our national model codes are applied locally to improve firefighter safety.

Sean DeCrane

Manager, Industry Relations UL LLC

Battalion Chief (Ret.), Cleveland (OH) Fire Department

IAFF Representative to Codes and Standards

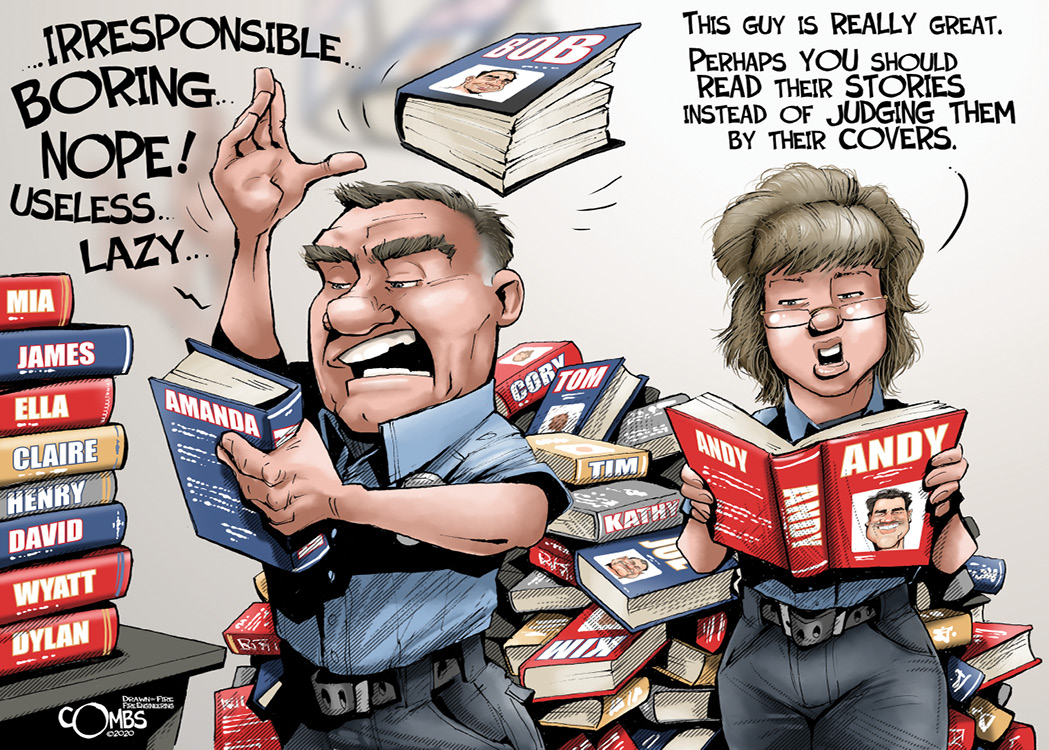

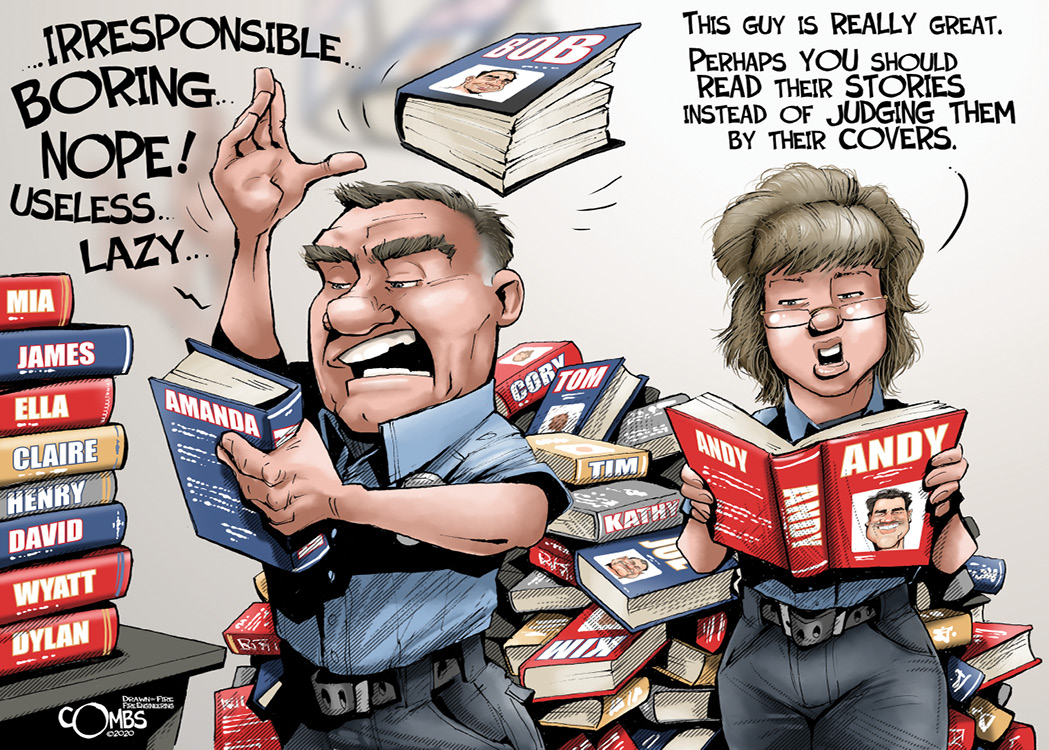

It’s not okay to not be okay!

Regardless of our new awareness of post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression, in spite of the fact that we say we are a brotherhood/sisterhood and that we will always have each other’s back, the truth of the matter is that it is still a closed subject. To be vulnerable and expose this weakness can be life changing and maybe even devastating to a career, a friendship, and even a family. It can be so devastating, in fact, that some would rather die by their own hand.

We say that we have grown to understand that these are wounds that can be healed, that we now know that it’s not a character flaw or weakness. Unfortunately, we still hold the same prejudice and biases that the person is flawed because of coming out and exposing his vulnerability. We are slowly accepting this at the peer level, but we are still extremely critical and prejudiced of anyone at a higher or lower level of rank or responsibility. No one wants a team member they feel can’t take the heat and step up or to be led by someone they feel may break under the pressure.

Even within our own peer structure, once a friend or coworker exposes a vulnerability, the relationship becomes tested because they fear they are viewed as being inferior. It goes back to our most primal instincts that we want to surround ourselves with the strong and we equally want to be viewed as a source of strength. We want to appear to be strong to our coworkers, our friends, and especially our family.

To break down in view of our loved ones is a devastating and sometimes life-changing event. There is always the fear that it will change how we are viewed and how others feel about us. It can be argued that if there is love, they will stand behind us or we will stand behind them. However, in many instances, this isn’t the case. The relationship changes from being equals to a rescuer/rescued situation with both sides feeling some resentment.

What is the solution? it’s not to talk to your coworkers, your friends, or even your family. Because of the level of risk, it’s not a viable solution. No one is going to take the chance on this level of risk. There is far too much to lose. For emergency services, we need to follow the lead of the military. We need a variety of accessible programs; the key is accessible. We need the ability to seek out help that doesn’t jeopardize our entire life. We need a selection of programs because no “one size fits all.” We need the ability to seek out help anonymously so that confidentiality is maintained to a level that satisfies the recipient.

Unfortunately, at this time, programs and services are few. While some have insurance to cover select services, most do not. Even those who have employee assistance programs, there will always be a concern about confidentiality. How do we get a variety of programs that have funding, are accessible, and maintain an individual’s anonymity? The first step is to recognize that telling individuals to talk it through is a bandage on a severe wound at best. And although it’s easy to list all we need, we need leadership in emergency services to make this a priority. We need dedicated funding at the state and federal levels to support program development. We need to educate ourselves on the facts and start grassroots movements in developing programs and supporting programs. What we truly need, what we need most of all, is true compassion and understanding. We need to start to believe that’s it’s okay to not be okay and to know that the wound can heal.

Recently, while discussing mental health issues in the fire service with a high-ranking officer, he made the comment that this was just the newest fad, like hazmat was a few years ago. I was a bit taken aback, even angered by his comment. In emergency services, we tend to be a little slow in grasping how dire the situation is. I argue that hazmat was an issue long before we acknowledged, regulated, trained, and now accept the dangers and have taken steps to protect responders. Mental health issues are not new in emergency services. I have lost colleagues during my entire 40-year career. These people were not weak and actually were some of the bravest, smartest, and best. All were people I wanted to follow or have my back in the fight. All are missed desperately by family and those they served with. All were heroes, the best of the best.

I have been retired for 15 months. In one month, I will have beat the odds for survival. I haven’t come through my career unscathed but consider myself fortunate. Until it becomes okay to not be okay, we are all living just day to day. There is no secret formula to dodging the effects of the job, physically and mentally. None of us can ever say it won’t happen to me. We can only say I made it through today until it is okay to not be okay.

Steve Schreck

Battalion Chief (Ret.)

Alaska Division of Fire and Life Safety

Volunteer, Alaska CISM Team

Alaska Firefighter Peer Support

Responders Promise Alaska (Equine Therapy for First Responders)

Drawn by Fire/Paul Combs