A New Look At Pre-Fire Planning

PRE-FIRE PLANNING

Pre-fire planning is one of the most valuable tools that a fire department has to aid firefighters in making an efficient and effective fire attack. By enabling the incident commander to draw up specific plans for firefighting operations at particular locations before the incident occurs, pre-fire planning can facilitate size-up, thereby shortening the decision-making time; pre-determine apparatus and hose placement, allowing for quicker attack; and identify important details, such as fire load, construction, type of occupancy, etc.

A well-developed pre-fire plan involves five very important parts:

- Information gathering

- Information analysis

- Information dissemination

- The “what if” syndrome

- Review and drill.

Information gathering is the collection of information that could affect operations on the fireground. The inspecting company should look for anything and everything that might help or hinder firefighting operations. The pre-fire planning process will be time-consuming when done right. No area should be overlooked.

Information analysis is determining which facts are pertinent and should be used to formulate the pre-fire plan.

Information dissemination is distribution of pre-fire planning information to all companies that might respond to the incident. These companies should get familiar with the pre-fire plan and should, preferably, train as a team.

“What if” is the analysis of the plan for possible events that might arise during a fire situation. Most pre-fire plans are for a given set of circumstances. Yet, how many fires have occurred exactly the way you predicted, or started where you predicted they would start? For example, the most probable places for hotel fires to start are in guest rooms or kitchens. The fire at the MGM Grand Hotel was reported to have started in a concealed space, and the fire at the Las Vegas Hilton was reported to have started in the corridor. Adjust your plan for those possibilities and areas considered to be the highest risk.

Review and drill is the periodic review of the pre-fire plan to ensure that the information you have is up-to-date. Periodic drills on the plan should be held to make sure that everyone is familiar with it.

The finished pre-fire plan should consist of two items: the data sheet and the building layout. To compile this information, you must look at six major areas:

- Number and type of occupants

- Type of occupancy

- Fire department response

- The fire building (access, suppression systems, water sources, fire load, construction)

- Exposures

- Utilities.

OCCUPANTS/OCCUPANCIES

Occupants is the first area of concern. Resident occupants are found in a building continually during its operation (hospitals, office buildings, etc.). Of these resident occupants, we must determine if any are non-ambulatory due to physical or mental handicaps.

Transient occupants are those who come and go in a building during its normal operation (theaters, restaurants, sports centers, etc.).

You also should determine the time of day and the day of the week that the building is occupied and the normal number of occupants. Knowing the occupant status and needs will give you the information necessary to identify any special search and rescue operations that should be performed; to strategically position ground ladders, aerials, and/or platforms; and to determine what additional equipment and manpower will be required and where hose streams should be placed.

We should also look at how the fire will be detected, as a delayed alarm usually adds to the urgency of the incident. Will the fire be detected by an occupant or by an automatic detector?

In most cases, you can figure on three to five minutes after a fire’s inception before an occupant will detect it. However, are there enough occupants to detect a fire? It is one thing to have five people occupying a 1,500-square-foot area and an entirely different situation to have one person occupying 5,000 square feet. Also, do the occupants’ activities make it hard for them to delect a fire? If most of the occupants move around the building continually, they stand a fairly good chance of detecting a fire. However, if their activities limit them to a certain area of the building, it’s likely that they could detect a fire only in that area, and that fires in the rest of the building would initially go unnoticed. Could the fire render the occupants unable to detect it? To answer this question, you must judge what effects the fire’s products of combustion will have on the occupants prior to discovery of the fire.

If detectors are present, are there a sufficient number to detect a fire? Is the system reliable in detecting fires? Was the system installed properly? What type system is it, smoke, heat, or rate of rise? If you are satisfied with the system’s operation, you can figure that a smoke detector will detect a fire within thirty seconds to one minute, while a heat detector will take one to three minutes to detect a fire, depending on how fast the heat builds up.

Next, you should look at how the fire department will be notified. Will the alarm come in by phone? Does the detection system alert an intermediate source who then calls the fire department? Is the detection system supervised directly by the fire department? If notification depends on an individual to call, it will take about two minutes for that person to decide to call and locate a phone. If the detection system alerts an intermediate source, then you must determine what the procedure is and the time it will take to notify you of an incident. If the detection system alert goes directly to the fire department, we assume immediate notification.

FIRE DEPARTMENT RESPONSE

Next, look at your alarm handling time. How long does it take your communications office to get the necessary information and sound the alarm? Then figure your turnout time. How long does it take to get to your apparatus and leave the station? The final part of this procedure is to figure travel time. How long does it take to get from the station to the incident scene?

By adding the detection time, notification time, alarm handling time, turnout time, and travel time, we now can estimate the time from the inception of the fire until the fire department arrives on the scene. For example, if fire detection in the building depends on occupants, this could take three minutes; for an occupant to notify the fire department would take an additional two minutes; and let’s say the alarm handling time is one minute. We are at a time of six minutes at this point. If we add a thirty-second minimum turnout time and a five-minute maximum travel time, we have a total of IIV2 minutes from the inception of the fire until the fire department arrives on the scene. Since the first five minutes of a fire are the most critical, we are starting out with one strike against us.

THE FIRE BUILDING

Access

Getting to the fire scene does not always get us to the fire, therefore, there are four types of access we should look at:

- Site

- Building

- Floor

- Room.

We look at site access for possible locked gates, blocked entrances, or any limited approach to the building. Perhaps we have free site access. We look at building access to determine how to enter the structure if it is locked. Where can we get the keys? What forcible entry might be needed? Or, can we simply walk into the building once we get there?

We then look at floor access from interior and exterior stairwells, exterior access by ladders, elevator access, and doors that may be locked or that might lock behind us. The final access is room access. Once we are in the building and on the floor, what doors to the room can we expect to be locked? Where are the keys to these rooms kept and, if these keys will not be available, what forcible entry will be required to enter the room?

Suppression systems/ water sources

The suppression devices built into the building and site will be the next area of concern. Note the location of all available hydrants in the area. The nearest hydrant will not always be available or satisfactory. Also, note the spacing of the hydrants so that you can pre-determine the hose lays needed.

Look for standpipe systems. Determine if these are wet or dry and where the fire department connections are located. Locate the sprinkler systems, the control valves, the fire department connections, and the type of sprinkler system it is (wet, dry, pre-action, or deluge). Locate additional water supplies such as private water storage, drafting ponds, etc.

Fire load/intensity

The next and probably most important step is to estimate the potential extent and intensity of the fire. In the past, we have used the formula: gallons per minute = LX W X H/100. Although this is a very good rule of thumb, the fire service is fast becoming an exactand predictable science. For this reason, I propose a new way of estimating the potential fire growth, which depends on the natural combustion characteristics of the fuel in an area. Bob Fitzgerald of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts developed a process that lets the building tell us how it will perform in a fire. Judging fire growth potential is just one small part of this process.

The relative ease and speed with which a fire can develop in a compartment (area of a building) depends on fuel (type, arrangement, interior finish), air supply, and room construction (ceiling height, compartment volume, compartment shape, compartment insulation).

Regarding the flame-heat output, we should be concerned with surface flame movement and fire severity. Surface flame movement is the ease with which the flame will spread across the area’s interior finish and the combustible surfaces of the contents. This is solely dependent on the number and placement of fuel packs in the area.

A fuel pack consists of combustibles located close enough together for flame contact. When a flame jumps a space, this indicates another fuel pack. If a fuel must be ignited by radiant, conducted, or convected heat, it is a new fuel pack.

There are two types of fuel packs, building fuel packs and content fuel packs. The building fuel packs are made of the same materials as the building, and if these fuel packs must be considered in the fire growth potential then it is too late. By that time we should be on the outside putting water on the fire (the building is written off).

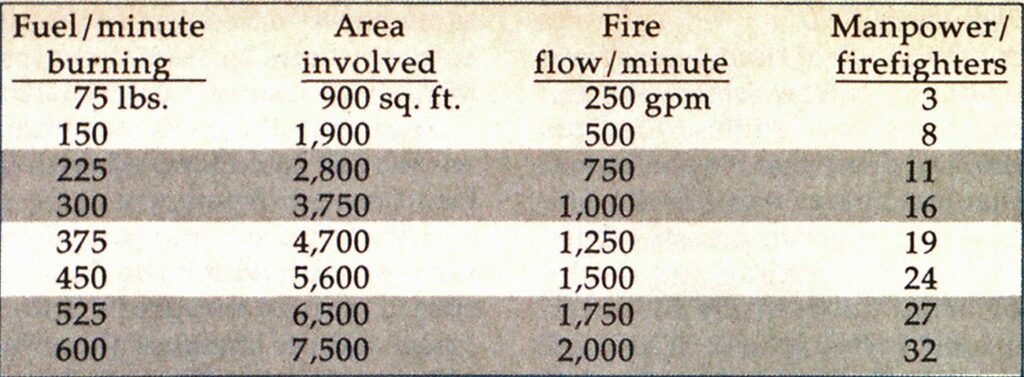

The content fuel packs are combustibles that were placed inside the building, and should be the only ones we consider. You should determine the number and the approximate weight of each fuel pack. The approximate weight is very important. Use this weight to estimate how much of the pack will be burning per minute when you arrive (pounds-per-minute burning rate). From this rate, we can determine the suppression forces and fire flow per minute necessary and the maximum square feet of fire that we can expect to find (see chart in next column). By determining one value, we can predict many important values needed to build an accurate pre-fire plan.

Construction

The next area we should look at is building features, including interior and exterior construction. With this we can predict the possibility of collapse during a fire. It is also important to record the building dimensions, height, length, width, and number of stories.

When looking at the roof, we should note three things: The first of these is the roof covering, which will indicate the tools needed to effect roof ventilation. The second is the roof condition, which will indicate roof stability and whether we should station anyone on it. The third is any natural opening that might be used for ventilation, reducing the need to cut open a vertical artery at the roof level.

EXPOSURES AND UTILITIES

Before leaving the building, two items must be noted. The first is all exposures surrounding the fire building, their locations, construction, occupancies, life loads, etc. The second is the location of utility disconnects for the building that you are pre-planning.

Now that we have this information, what should we do with it? As stated before, the pre-fire plan consists of two parts, the data sheet and the building layout.

DATA SHEET

The data sheet should consist of information that the officer should have at his fingertips at the fire scene. Remember, this is something he may have to read at 3 A.M. after coming out of a dead sleep. A sample of data information that may be helpful could include:

Address:

Owner/Telephone number:

Occupant/Telephone number:

Alarm company telephone number:

Number of occupants:

Time of occupancy:

Days of occupancy:

Standpipe connection location:

Sprinkler connection location:

Ventilation requirements:

Construction:

Roof covering:

Exposures

Location:

Name:

Construction:

Key locations:

BUILDING LAYOUT

After the data sheet, it is time to develop the building layout. This is a map of the building with three views covering the site location, floor plans, and roof plans.

Site location

The site plan should identify the building being pre-fire planned by cross-hatching it on the map. The crosshatch should end where there is a fire wall or where the building ends. The number of stories and dimensions of the fire building and any adjacent buildings should be indicated. The boundary line for the lot on which the building is located should also be indicated. This map should show all fences; parking areas and their access; outside storage areas with contents; and access routes, streets, alleys, and areas between buildings. Everything on the map should be marked plainly with the business names and addresses of all buildings. These plans should be drawn as if you were looking at the front of the fire building. Along with the above items, all hydrants and overhead utilities and the northern direction should be identified.

Floor plan

The floor plan should be for typical floors. Just because there are 20 floors is no reason to have 20 floor plans. But, if a floor’s arrangement changes, we need another plan. Indicate the number of typical floors represented by each floor plan and their floor numbers.

The floor plan should indicate the entrances as seen from the front of the building. The rooms, halls, corridors, stair locations, utility cutoffs, and any storage (type and special hazards) should be clearly marked and identified.

It is important to mark vertical openings, such as elevators or dumbwaiters. These openings not only allow people and item movement, but smoke and heat movement too. It is also important to note the location of any standpipe connections, sprinkler control valves, and supply pumps on the floors.

Roof plan

The third and final part of the building layout is the roof plan. The roof plan should be drawn to the same scale as the floor plans. The roof plan should indicate elevator equipment, skylights, any vertical openings, etc. You might also indicate the location of water tanks; antennas; dishes; heating, venting, and air conditioning units; utility lines; or anything that creates weight.

With proper preparation, proper drilling, and proper use, pre-fire planning can be one of the best tools a fire department has to facilitate the handling of an incident.