FEATURES

TRAINING

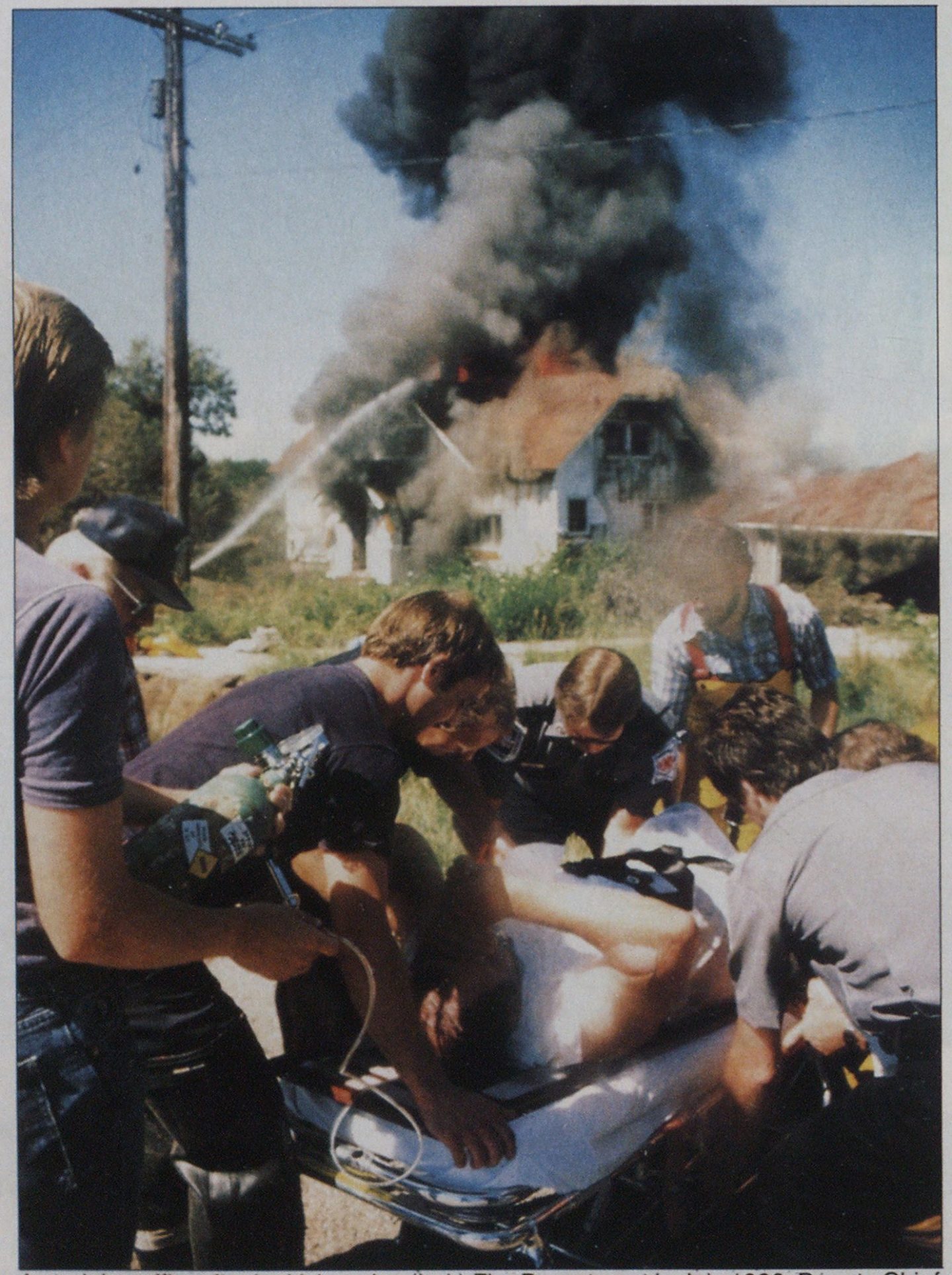

(Photo by John Wozniak)

Training Fires: Lessons vs. Risks

If they’re used, training fires must be conducted safely. But fire departments should consider not using them at all.

Recently, three Milford, Mich., firefighters were burned to death during a “routine” training exercise in a 120-year-old abandoned building. This fire was started and accelerated by training officers using flammable liquids. The incident echoed a past tragedy, in which two Boulder, Colo., firefighters lost their lives on January 26, 1982, during a “controlled” fire in a small, abandoned shed.

Firefighting is, unfortunately, one of the most dangerous occupations in America. Many of the inherent dangers commonly encountered on the fireground, such as roof collapse, backdraft explosions, and flashovers, cannot be readily eliminated and have become accepted risks. Firefighting is hazardous enough without needlessly increasing the danger through carelessly planned and haphazardly executed training fires. Thus, injury and death are especially tragic on the training ground since, unlike “regular” fires, most hazards on the training ground can be controlled or eliminated, much of the danger reduced, and most injuries and deaths prevented.

Deaths on the training ground underscore several salient fire service training needs. First, fire departments must recognize the National Fire Protection Association’s Standard 1403, “Live Fire Training Evolutions in Structures,” by adopting and enforcing these recommended training procedures at the local level. Furthermore, state fire marshals and training directors must take a stronger leadership and enforcement role toward training-fire safety within their states. But most important, fire chiefs, training officers, and firefighters must radically adjust their attitudes about inside-attack training fires altogether.

Many fire service members have a dangerously passive, if not cavalier, attitude about training-fire safety. Some mistakenly believe a training fire somehow becomes routine and less dangerous if ignited and “controlled” by firefighters themselves. Examples of this totally inappropriate attitude are reflected in statements I’ve heard from fire chiefs—”Training fires are just routine fires,” “Training fires are controlled burns,” and “We’re hoping to expose our new firefighters to flashover conditions so they’ll be ready for the real thing.”

Training fires are no different from unplanned fires and should never be considered just routine. The behavior of a training fire is as unpredictable as that of a “real” fire and, for several reasons, frequently more dangerous.

First, most burn buildings are old farmhouses or out-buildings which have been abandoned for some time. Important components of their history of use and renovation usually aren’t available or are recorded inaccurately. Such structures often have been used to store flammable or combustible liquids, explosives such as dynamite, or toxic pesticides and chemicals.

These hazardous materials may be on the premises—hidden in piles of debris, tucked away in an attic, or stuffed in the walls—unknown to the building owner and the firefighters.

Furthermore, every unfriendly fire—including a training fire—is dangerous. Even the most experienced firefighters in the nation’s largest cities know the inherent dangers of every fire, no matter how routine the fire call seems. These firefighters “have seen it all,” but they still respect every unfriendly fire as a potentially deadly encounter. Every fire chief, training officer, and firefighter must adopt the same professional attitude toward training fires, which are, in fact, the real thing.

Finally, we need to recognize and acknowledge that a training fire is definitely not a “controlled” burn. Can any training fire that’s ignited and accelerated with flammable liquids such as gasoline be controlled? At what point in our fire service careers do we become experts in the use—or, more appropriately, the misuse—of flammable liquids? Tenure doesn’t qualify a firefighter as a pyrotechnician; the suppression or extinguishment of fires doesn’t necessarily correspond to expertise in starting fires. Does any fire department in America provide its firefighters with special training in the misuse of flammable liquids as accelerants? Hopefully not one!

Consider the irony: One of the fire prevention messages the fire service perennially attempts to communicate to the American public is the proper use of flammable liquids. Yet some departments continue to allow firefighters and training officers to misuse gasoline as a training fire accelerant, and the result sometimes is injury or death. What kind of fire and life safety example are we setting?

Local fire chiefs must therefore formulate, adopt, and enforce a comprehensive training fire policy. This must include a standard operating procedure set up under the guidelines of NFPA 1403. At a minimum, include the following:

- Designate a training-fire safety, or burn, officer for the long

- term. A person who has the role consistently has the chance to research and study proper procedure. This firefighter should have control over the planning and execution of the fire. The burn officer must have enough authority to stop all unsafe activities at the training fireground, including prohibiting firefighters from entering the building, if necessary.

- Consult a structural engineer. Most firefighters don’t have the engineering background to fully evaluate the structural integrity of a proposed burn building. Consult a structural engineer from your jurisdiction’s building department.

- Consult the utility company. Ask your local gas and electric company field technicians to assist in the prefire safety inspection of the proposed burn building. These professionals can locate utility hook-ups and may recognize abandoned, energized electrical lines and active gas supplies.

- Tour the building. Every firefighter intending to enter the building (including attack and back-up crews), the safety officer, the building department’s structural engineer, and the utility company’s representatives should tour the building several times. All escape routes should be predetermined, and additional egress points should be cut in the wall if the number of existing exits is insufficient.

- Assign safety station officers to each proposed entry point. These officers should carefully inspect the incoming crews to ensure that every firefighter has a fully charged self-contained breathing apparatus, turnout coat and pants, boots, gloves, helmet, and protective hood. Additionally, station officers must keep an accurate count of all firefighters entering and exiting the building.

- Hold a chalk talk. Several days before the scheduled training fire, thoroughly discuss the training fire scene. Underscore the need for firefighter safety and carefully review all escape routes and exits. Make assignments for the engineer, rescue crews, back-up crews, and safety station officers at this time.

Agree on an evacuation alarm. Designate an unmistakable and readily audible emergency alert signal for the training fire exercise. An apparatus air horn, for example, could be used to alert all firefighters in and near the building to immediately evacuate to a designated, safe area. Safety officers should then account for every firefighter.

- Precut ventilation holes. Firefighters should precut ventilation holes in the roof of the building, and firefighters should be assigned to quickly remove the “covers” if problems such as flashover conditions develop.

- Forbid flammable liquids. The use of any flammable liquids or other hydrocarbon accelerants should be absolutely forbidden. Only Class A materials should be used. Ignition may be assisted by small amounts of properly stored, combustible liquid such as uncontaminated diesel fuel or kerosene.

- Provide a two-to-one firefighter safety margin. For every firefighter allowed into the build-

- ing, two firefighters equipped with full protective clothing and selfcontained breathing apparatus shall stand by with charged hose lines. Each of these teams should be at a separate entry point.

- Forbid red lines. Red lines or booster lines should not be allowed for firefighting purposes.

- Require 1 Vi-inch firefighting lines at minimum. This is the standard size for inside attack.

- Require two 2V2-inch back-up lines at minimum. These will provide quick knockdown if the primary team gets in trouble.

- Use more than one engine. Attack, back-up, and rescue crew hose lines should not be dependent on a single pumper. Ensure that at least two engines are in service on the training fireground, and use only trained and qualified engineers.

In sum, it’s time the fire service faces several undeniable facts.

First, inside-attack training fires accelerated by flammable liquids cause an unacceptably high firefighter safety risk.

Moreover, most communities, thankfully, don’t have enough fires to keep firefighting skills finely tuned, and annual or biannual training fires aren’t going to make up the difference. Internal-attack training exercises do almost nothing to enhance long-term knowledge and skills. There are a myriad of effective, less dangerous, and almost as realistic methods available, such as training with smokegenerating devices or blackened masks for search and rescue, or extinguishing fires outdoors.

The ultimate responsibility for firefighter safety on the training ground rests with local fire chiefs, not exclusively with the department’s training officers. Every fire chief must formulate a comprehensive training fire standard and ensure that everyone on the training ground operates within mandated safety parameters.

As a first step, the prudent fire chief should reevaluate altogether the potential costs in firefighter lives and the marginal value of inside-attack training fires.