By David Mellen

There are few things more vital to firefighters during fireground operations than communication. Every form of it is essential to the successful resolution of an emergency, from a radio report to inform incoming fire apparatus of on-scene conditions to a face-to-face discussion with the incident commander (IC) that will dictate what tactical decisions are made. One of the most essential and often least discussed forms is inter-crew communication. Everyone from a probationary firefighter all the way up to the chief must be able to perform this task to ensure that the crews operating on the fireground hear communications and understand them, as well.

Good inter-crew communications can make the difference between a successful and a disastrous outcome. Just as in other highly dangerous professions, the ability to receive a message clearly and immediately interpret and understand it can make the difference between life and death. As technology, tactics, and personal protective equipment (PPE) have developed over the years, so have our means of communicating with each other. The days of pulling your mask away from your face to yell louder are gone–you now turn on a voice amplifier. Hand signals and shoulder taps have been replaced by intercom systems that are integrated into radios and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). Unfortunately, most of this technology is still expensive and therefore a luxury rather than a requirement.

On the fireground, communicating face-to-face can become difficult when there is a lot of noise, but usually we can decipher the intended message by means of lip-reading, hand signals, and the occasional piece of equipment flying towards us. The problem comes once we’ve donned our SCBA and entered an Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health (IDLH) environment. At this point, we’ve lost our ability to pick up on non-verbal cues, therefore limiting our ability to piece together the message. Most of us have been there–inside of a fire or standing on a roof with a crew and someone start talking to you only to sound like Charlie Brown’s teacher. After several attempts, you just can’t seem to understand what they are telling you. It’s frustrating but, more importantly, it’s dangerous. Not understanding a simple command can aggravate your fellow firefighters, but not recognizing “the floor is gone” can be deadly.

Recently, one of our assistant chiefs developed a training specific to inter-crew communications that quickly became known as “The blind leading the blind.” It reinforces solid crew communications and teamwork. During the first training, we used the analogy of yawning. When you are surrounded by friends and family and you yawn mid-sentence, they can usually decipher your words and understand what your intended message was. If you repeated that same action in a group of people you don’t know, most of the time you are met with stares and pondering expressions. This is a great example of the obstacle we run into on the fireground while trying to communicate with one another.

What you will need

- An area large enough to accommodate a 25-foot wide circle around each team.

- Team(s) of two firefighters in full PPE, including radios.

- One SCBA per team.

- Evaluator(s) (we found that an evaluator to firefighter ratio of less than 1:6 works the best).

- Stopwatch, paper, writing utensil.

- Camcorder, if possible.

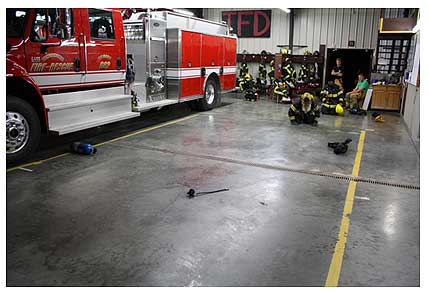

Set up

- Completely disassemble one of the self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) (i.e., quick coupler hoses, cylinder, harness, bailout bag, etc.)

- Both firefighters don only an SCBA mask, with one firefighter limiting visibility by using wax paper (or in this case, a reversed hood.)

- Have an evaluator disperse the parts of the disassembled SCBA randomly throughout the circle.

Execution

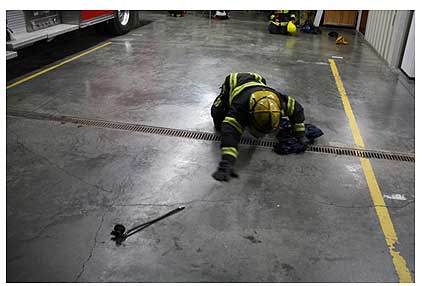

- Starting the timer begins the evolution.

- The firefighter able to see will direct the firefighter with limited visibility to the location of the parts of the SCBA using basic commands such as left, right, stop, forward, etc. Firefighters should freely communicate throughout the entire evolution so that differences in voice quality can be observed at different distances.

- When all of the SCBA components have been found, the firefighter giving directions should guide the other firefighter back to the original start point. At this point, the firefighters will switch roles.

- Give only verbal commands on how to reassemble the SCBA step by step, making certain not to physically touch any part of the SCBA.

- Once the SCBA is reassembled and donned completely, the time stops.

Reviewing the Evolution

Once the team has completed the evolution, have them remove their SCBAs and allow time for discussion. As some of our newer firefighters discovered, it was much harder than they expected to give and receive commands, even in a quiet environment. Evaluators can rank the teams from the fastest to slowest time. This evolution can be repeated by switching firefighter roles and eventually rotating firefighters through different teams so that everyone gets a chance to work with someone new. Once the evolution is completed in its entirety, you can give times for all teams and individual firefighters.

Scalability

This training can be expanded to include radios, external noise sources such as vent fans or pass alarms, and any other added needs that are specific to your department. Once the firefighters have become comfortable with deciphering what crew members are saying, throw in something new to change it up a bit.

***

Learning how to understand one another even in the worst situations can and will be difficult to achieve, but it’s a necessary skill to ensure that what is spoken will be understood and carried out. As firefighters, our job depends on communication and teamwork, without either one of which our abilities diminish drastically. By being proactive in our training, we can identify deficits with our communication skills before it becomes an issue on the fireground.

David Mellen is an 13-year veteran of the fire service and currently a Firefighter/Paramedic with both the City of Tonganoxie (KS) Fire Department and Reno Township (KS) Volunteer Fire Department. Mellen began his fire service career as a Fire Service Explorer. He can be reached at firemedic1371@hotmail.com