Studying For Promotional Exams: The Mechanisms of Human Memory

FEATURES

EDUCATION

Part I

The firefighter who wishes to rise through the ranks and be part of the managing team must acquire special knowledge and certain skills and abilities over the years. This will eventually separate the outstanding firefighter from the average firefighter.

However, knowledge and skills are not the only criteria. Many firefighters throughout the country, especially those in metropolitan areas, will have to achieve a relatively high score on an extremely competitive examination in order to be promoted to a higher rank.

Although most promotional exams are carefully designed to select “the best candidate” for the job, this is not always the case. Unfortunately, the firefighters with the best skills and/or experience are not necessarily the ones who do well on exams. Everyone probably knows a story about a fellow firefighter who has the qualifications to be an excellent officer, but does not get the promotion because he consistently scores low grades on promotional exams.

Most testing experts would probably agree that even sophisticated testing techniques do not always select the “best candidate” for the job. As a result, it is often the “good student” and not the “good firefighter” who gets the higher score and is subsequently promoted.

Still, the paper and pencil test is the most practical and objective method. It is also the most frequently used tool to promote firefighters to officer ranks.

An effective way to prepare for these exams is to become familiar with the types of questions that may appear on them. Unfortunately, depending on the municipality, sample exams are not always released to the public. In addition, the exam format may change from one test to the next or from one promotional rank to the next. The popular multiple-choice method is quickly being replaced by a combination of other types of tests such as essay, oral, in-basket multiple choice, assessment centers, etc. Because of these changes, studying from previous exams may not be an effective form of preparation. Nevertheless, knowing how exams are prepared can be useful information for the test taker (see “Multiple Choice Questions for Tests” by Richard W. Shelly, FIRE ENGINEERING, February 1981).

When it comes to studying for an upcoming exam, there are many strategies you can use. Some people set aside a number of hours per week or per day to study, and they will religiously adhere to this schedule no matter what is happening around them. Many “selfhelp” books on memory discuss the importance of these and other study habits, such as your posture while reading.

However, what truly matters in this game is that you must provide the correct answers to most of the questions on whatever exam you are taking. The best way to do this is to learn the material and be able to retrieve it efficiently on the day of the exam. This article will give you an overview of the way information is learned, stored, and retrieved from memory, based on the latest findings in the field of cognitive psychology. (This is the branch of psychology that studies the various aspects of the processing of information.)

SOME COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT MEMORY

Recognition vs. recall

Because of the many misconceptions about the nature of learning and memory, “good preparation” for an upcoming examination can mean different things to different people. Indeed, our everyday language shows that most of us have a rather poor understanding of our memory processes and how we remember past experiences.

For example, we have often heard people say upon meeting a familiar person “I know you; I never forget a face.” However, when it comes time to remembering someone’s name, perhaps under the same circumstances, we may say “I can never remember people’s names.” These two statements reflect two distinct memory processes.

Most of the time, the first statement refers to the mechanism of recognition — matching information from the environment with information that had been previously stored in our memory. The second statement refers to the mechanism of recall—retrieving information from our memories.

For our purposes, the distinction between these two mechanisms is important. In multiple choice questions we may be able to use recognition, whereas in essay-type exams we primarily rely on recall. As you probably have noticed, we recognize much more material than we can recall.

The brain’s capacity for storing information

One of the most common misconceptions about memory or the brain in general is that “we use only 10% or 15% of our brains in thinking, remembering, and processing information.” In fact, there is no scientific evidence for this statement because it is not known what limits a human brain has for storing and processing large quantities of information over long periods of time (see the discussion on longand short-term memory later in the article).

Unlikely as it may sound to you, it is possible that the human brain may very well have an infinite capacity for storing information. A good example to illustrate this is people who learn three or more languages. Think of the huge amount of storage necessary to file all of those words!

Spaced vs. distributed practice

Most of us spend many hours studying department regulations and procedures, instruction manuals, etc. One common misconception is that the more time you spend studying, the more you are going to learn. This is not necessarily true all the time. Effective learning depends on how much attention you pay to the information you are studying and the rehearsing strategies you use to memorize the information.

Investigators of human learning and memory have found that the more intense your rehearsing strategies are, the easier it will be for you to recall previously learned information. For example, “cramming” — studying large amounts of information just before the exam—is known to be a poor strategy for learning. A more effective method is to study for the same amount of time, but distribute the study time at equal intervals over a few weeks before the exam.

When you cram, there is not much time left to rehearse the material that you are studying between the beginning and the end of the cramming session. However, if you distribute the study sessions over a number of intervals, you have more time to rehearse the information and a greater chance of retaining the material.

THE CURRENT MEMORY MODEL

The latest models on how we process information have been borrowed primarily from the fields of computer science and artificial intelligence. (See the Microcomputer Series by Michael Fay in the October, November, December 1984 and February 1985 issues of FIRE ENGINEERING. These four articles cover the use of computers in the fire and EMS services and can familiarize you with some computer terminology.)

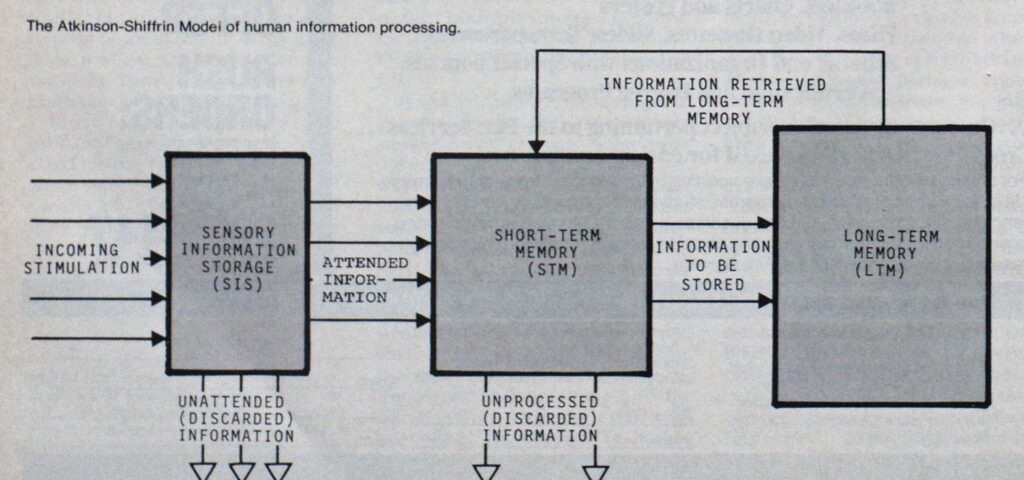

One of the most popular conceptual models of memory is the Atkinson-Shiffrin Model (see figure on page xx). This model uses three container-like structures that are involved in receiving, encoding, storing, and retrieving information.

The first container is called the sensory information storage (SIS). This is the first place to receive all incoming information that is picked up by the senses. In essence, this structure receives every bit of raw (unprocessed) data from the environment and retains it for a fraction of a second, for purposes of encoding. As the SIS processes the array of data, the important information is selected and sent to short-term memory (STM), while the rest is discarded.

Again, important information is maintained in STM while unwanted material is discarded. The remaining important information is then sent to long-term memory (LTM) where it is stored indefinitely, depending on the quantity and quality of rehearsal. In LTM, the information may be retrieved back to STM for a brief examination and stored again in LTM.

Information may be kept in STM for as long as we rehearse it. In other words, STM is our present conscious experience. When new material enters STM, the information that was there is automatically discarded or sent back to LTM.

Shortand long-term memory at work

We can illustrate how the system works by examining what may be occurring in your own memory system as you read this article. As you read, all of the information that is impinging on your five sense organs is initially processed by the SIS—every sound, every (tactual) sensation, every color contrast between the letters and the whiteness of the page, etc. Yet, only a small fraction of these elements with which you are bombarded reach your conscious awareness. In this case, it will be mostly the printed words on the page.

If you are truly concentrating on the writing itself, your primary awareness is that of the meaning of what you are reading. This information is what is presently being processed in STM. Whatever other stimulation you are receiving goes through the SIS, but most of it is probably discarded. Only “important” information is sent over to STM, and everything there represents your present conscious experience. Once the information is in STM, it can either receive further processing—as when you are reading a sensational headline, an absorbing book, or, hopefully, this article—or the information can be discarded—as when you are skimming through the articles in a newspaper or the advertisements in a magazine.

The levels of processing information

The levels of processing, or the quantity and quality of rehearsal of information, can range from shallow to deep. The information that is further processed in STM is then sent to LTM where it can either stay indefinitely or be brought back to STM when it is recalled.

Your ability to recall information from LTM depends on the level or depth of processing that occurs in STM. That is the quality of the rehearsal. The deeper one processes the information, the longer it will last in LTM and the easier it will be to retrieve. Theoretically, the more times you rehearse the information, the stronger that memory trace will be and the easier it will be to retrieve.

How do the levels of processing information work? An example of shallow level processing is to mechanically repeat a list of words without thinking about their meaning. An example of deep level processing is to intentionally produce an associated image or other more complicated strategy to remember information. Some artificial strategies that can enhance deep level processing will be discussed in Part II of this article.

How deeply you process certain information may depend on how motivated you are to learn it. Say you are studying certain sections of the federal or local building codes because you will be inspecting a home that you are considering purchasing. Your motivation in learning the material and in later recall will be greater under these circumstances than if you were studying the same information for an exam. If, like most students, you are not very excited about studying for an exam, but are very excited about buying a home, you will have better recall in the second case than in the first case. The “intensity” of each reading is different.

The levels of processing at work

Let’s consider how you may process the information in this article. The depth of processing of this material will, of course, depend on how interesting you find this article. If you are about to take a promotional exam, chances are you will be more motivated to read it than if you are not planning to take such an exam in the near future.

If you will be taking an exam, as you read this article the information should find its way to LTM where it may stay for some time until the proper occasion arises for its recall. One such occasion may be a conversation with a fellow firefighter about the usefulness of this article. An even more appropriate situation would be just before you begin a study session for an upcoming exam. Hopefully, that’s when some of the information on memory strategies from this article will be recalled from your LTM.

When you read interesting material, several mental processes usually are activated that allow you to process the information at a deep level. Again, in the case of this article, you may find that as you read it you are producing images or verbal associations that are related to the information. These images and associations are mentally encoded with the information read. At the time of recall, the images and associations are then used to retrieve the information.

Interestingly enough, if later on you refer back to the information in the article or comment about it with a fellow firefighter, the actual recall of the information constitutes additional rehearsal of the material in STM. The information is further reinforced by additional deep-level processing, which strengthens the memory traces representing this material. Depending on the nature of rehearsal, each time you rehearse information it goes to “a deeper” level.

On the other hand, if you find the article boring and you catch yourself daydreaming or thinking about something other than what you are reading, these intervening thoughts will be processed in your STM. Shallow-level processing of your reading material is occurring because of the competition with other thoughts. This will lead to very weak memory traces, and the information will be difficult to retrieve or perhaps become irretrievable from LTM.

You can strengthen memory traces through deep-level processing with a variety of strategies. Researchers in the field have found that the more you are “personally involved” in learning a particular piece of information, the easier it will be for you to recall that material.

The example of studying the building code for the purposes of buying one’s own house represents one instance of “personal involvement.” A more dramatic example involves learning about the proper operation of a hydraulic rescue tool. Actually operating the tool under close supervision is much more effective than merely reading the operating manual. Working with the tool further strengthens the memory traces by adding a new dimension of sensory stimulation, including auditory and tactual sensations.

Unfortunately, it is not always practical or possible to have access to this kind of “hands-on” experience to enhance the learning process. That is why you must rely primarily on written material to study for exams. In addition, and more importantly, it is likely that most fire departments give promotional exams that are based on written sources: local fire department regulations and procedures; magazine articles; or texts on different aspects of firefighting, building construction, arson investigation, etc. In Part II of this article, which will be published in an upcoming issue, I will describe the various memory enhancing strategies that you can use to study for these exams.