Risk Management: Alcohol and the Social Drinker

features

HEALTH

There is little doubt that most firefighters are aware of the effects that alcoholic beverages have on their firefighting skills. That ethyl alcohol (the particular alcohol that is present in all beers, wines, and liquors) is a central nervous system depressant that negatively affects judgement, vision, reflex, concentration, coordination, comprehension, and respiration is generally well-drilled by safety officers. What is not widely known, however, is how low the threshold of these effects is.

Like it or not, there is a good deal of drinking associated with the fire service. Indeed, in our society at large there is a good deal of drinking. We are not talking here of people who use alcohol as a maladaptive coping mechanism (problem drinkers), nor of people who are addicted to the substance ethyl alcohol and experience a need to drink (alcoholics). Rather, we are addressing the largest classification of drinkers, those who can control their drinking and most often use alcohol as a mood changer (social drinkers).

Because the word “social” has an entirely different meaning in other contexts, this leads to a lot of confusion when the word is used in reference to drinking patterns. Simply put, a “social drinker” is one who is in control of his drinking. He may drink a beer by himself every night and still be a social drinker. Conversely, many folks who have problems with their drinking insist that they only “have a few to be sociable,” and incorrectly reason that this qualifies them as “social drinkers.”

Most estimates have social drinkers comprising about 75% of any drinking population. We can reasonably assume therefore that social drinkers constitute the largest segment of drinking firefighters in your department. Some will argue that firefighters have a higher incidence of alcohol abuse because of such diverse factors as “stress” in busy companies and “time on their hands” in slower units. However, it appears that, in the absence of any research to support these positions, it may be that there is simply a heightened awareness of whatever incidence of drinking there is.

Most departments have very stringent regulations regarding the consumption of alcoholic beverages either while on duty or immediately prior to reporting for duty. Because of concern for performance of a very physical and dangerous job, the penalty imposed upon a firefighter who is “busted” for infractions of such regulations is often made an example of to the “troops.”

For many members of the fire service, because of commonality of interest, shared economic class, and due to considerations of shared social structure such as the firefighter’s work schedule, the majority of their socializing involves other firefighters.

Many departments, as a natural outgrowth of the esprit de corps that characterizes much of the fire service, or in order to raise funds, sponsor social functions. At most of these social events, alcohol is consumed, and largely by social drinkers. Yet many of the participants are, unknown to themselves, their colleagues, and their departments, at substantial risk because of their drinking. Periodically, we hear of just as many firefighters being arrested for driving while intoxicated (DWI) as members of other occupational groups. Although, while on duty, firefighters are often the first on the scene at what is frequently the tragic consequence of drinking and driving, this does not seem to significantly deter their own use of alcohol when facing potential driving situations. How can it happen that this unwitting risk is being taken?

The answer probably lies in the same area as the key to the behavior of the average person arrested for DWI. Studies show that three quarters of those arrested for DWI, first offense, are social drinkers. A comment frequently heard from these folks is, “If I had known that I was that drunk, I never would have driven.” Most often, these offenders are, contrary to popular thought, ordinary people. They are not jobless sociopaths drinking out of brown paper bags. Nor, for the most part, are they people who have any problem with alcohol. They are people who have a sense of social responsibility and are mortified by what they have done. For most, prior to their arrest, they could not even conceive of their being arrested for anything. When they are in social situations where alcohol is involved and they are driving, they usually subject themselves to some sort of introspective assessment before they get in their cars. In fact, the question they usually ask themselves is, “Am I drunk?”

The issue of DWI has become the focus of a tremendous surge of national energy to prevent loss of life and property. Nightly television network breaks, movie stars, and athletes all advise us, “Don’t drink and drive!” We have Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), Students Against Drunk Driving (SADD), Bartenders Against Drunk Driving (BADD), and every elected official in creation taking up the battle. “Drunk driving” is a catchy phrase. It has a nice alliterative quality about it which lends it to use in headlines and speeches; and this has served our society well in raising general awareness of the issue. Paradoxically, though, it is this very phrase itself which often leads people to proceed at risk with a false sense of security.

What is it that people are thinking of when they ask themselves the question “Am I drunk?”? Aside from the fact that a person’s ability to be self-critical is as surely depressed by alcohol as are his reflexes, there is the problem that drunkenness is a subjective concept. The town “drunk” is one thing. I got “drunk” is something else. Neither means anything specific.

In deciding whether or not to drive (or if you are fit for duty), the question to ask is not “Am I drunk?”, but rather, “Am I impaired?” We get impaired long before we get drunk because most of us have a concept of drunk which tends to be defined as “grossly out of control.” This comes from popular images of the “drunk” such as Dean Martin, Foster Brooks, W. C. Fields, various Jackie Gleason characters, and the skits of several generations of stand-up comedians. When people examine themselves for drunkenness by these standards, they usually pass muster.

After a typical DWI arrest, a person frequently feels outrage towards the police officer. “He must have been wrong because I felt fine.” Well, feeling fine is not a criterion for deciding if you are impaired for the purposes of operating a motor vehicle. In fact, at .10% blood alcohol concentration (BAC)—this is one part alcohol for each thousand parts of blood—the limit defined in most states as prima facie evidence of impairment, you are probably feeling better than “fine.” You are on your way to euphoria.

Other bits of “evidence” that folks use to argue against their arrest usually involve the successful completion of tasks before the arrest. “Drunk? How could I have been drunk? I gave the speech at the dinner! I was dancing! I was able to count my change at the bar! I was able to get my key in the car door!” All of these things may well have been done successfully. But all they indicate is that you were not impaired to the point where you could not have done them. For, another key to the puzzle is the situational nature of impairment.

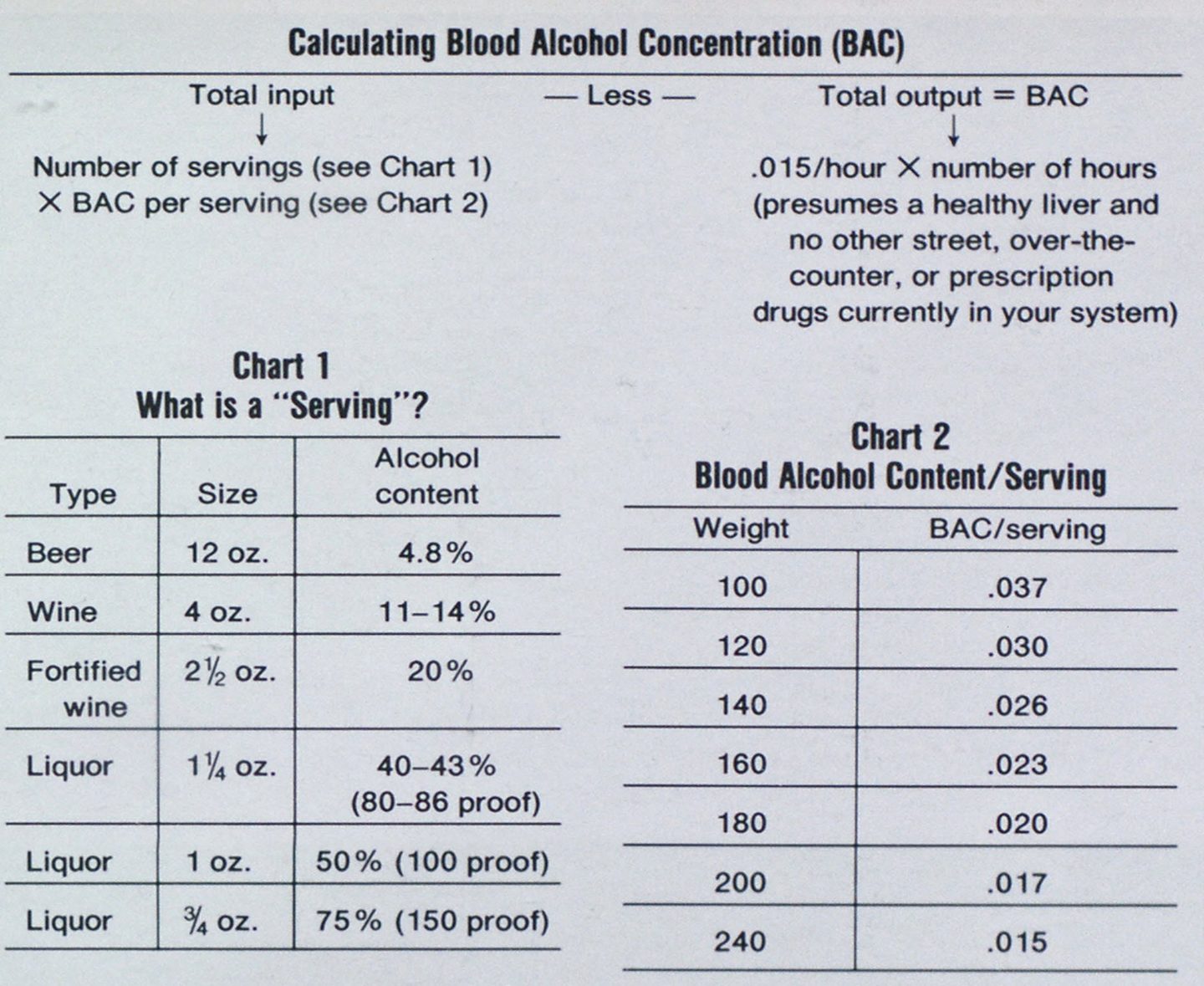

Take a 150-pound person who watches a three-hour football game on television. During the game, he has a six-pack of 12ounce domestic beer. Not too many folks among us would identify two beers an hour for three hours as an inordinate amount of drinking. Yet, assuming that this person has a healthy liver and is not taking any medication, at the end of the game, he has a BAC in the vicinity of .13%. We give an approximate number since what he was eating during this time, or immediately before it, can have a tempering effect on peak BAC. Nonetheless, this person is over the .10% which most people are aware of.

The question now is: Is he impaired? Before that question can be answered, you have to ask another: Impaired for what purpose? If he plans to drive a car, he is most definitely impaired. For the driving situation requires very specific and sophisticated skills; every one of which is dangerously depressed at a BAC at or above .10%. If, however, he simply plans to sit back and read the paper or watch another ballgame, that is a different situation. When judging our suitability to safely perform certain tasks, the successful completion of earlier tasks is only germane if the tasks were comparably demanding.

So, if the question is one of impairment rather than drunkenness, and impairment is a function of BAC, what constitutes your blood alcohol concentration? For one thing, your body weight is a major factor. Larger people have more blood (which generally is one-twelfth to one-fourteenth of your total weight), and therefore it follows that more alcohol would be needed to reach a .10% BAC. Pocket BAC charts are frequently available in liquor stores and magazines, and are keyed to alcohol intake and weight. What they don’t tell you is that you should subtract your overweight before doing your calculations. This is done because fat tissue generally does not get as good blood service as muscles and organs (the next time you cut into a steak, note where the juice comes from).

Also when using the BAC charts, the word “serving” is often used, as in so many “servings” per hour at a certain weight level. In order to get any use of the chart though, it is necessary to define “serving.” You will note in the example above of our friend watching the football game, I very specifically quantified his input: six 12-ounce domestic beers. From this, it should be clear that he is not drinking “pounders,” the 16ounce cans which contain one and a third “servings” each; that he is not drinking a foreign beverage which frequently has a higher alcohol content; and that he is not drinking malt liquor, which is often thought of interchangeably with beer but can have up to triple the alcohol content of domestic beer.

When speaking of other alcoholic beverages, the specifics are just as important. The “proof” is a crucial number to know when consuming distilled spirits. A standard “serving” of 80-proof liquor (that is 40% alcohol by volume) is one and a quarter ounces. If you freehand pour your drinks, you may find that you are using two to three times this amount. If you are a fan of 100-proof beverages, you should know that the standard serving goes down to one ounce. And if you prefer some of the stronger rums at 150 proof, your serving is three-quarters of an ounce. Some of the more exotic mixed drinks use up to five or six different kinds of liquor in each drink. It should be obvious that a “drink” is not a “serving.”

If you are a wine drinker, you should know that a standard serving of regular wine (11% to 14% alcohol by volume) is four ounces. This is about two-thirds of a standard wine glass, which is designed not to be filled. If you drink a fortified wine (such as many of the cream sherries and “dessert” wines), you should know that you have a fermented beverage to which distilled alcohol has been added. Consequently, a fortified wine is about 20% alcohol by volume and the standard serving is about 2.5 ounces. And, there is an elimination factor which, for a healthy person not taking any medication, is keyed to time at a rate of .015% per hour.

All of this sounds like an awful lot of data to assimilate just to “go out and have a few drinks,” doesn’t it? The fact is, in addition to being the central nervous system depressant that we have already noted, ethyl alcohol is also a diuretic, an anesthetic, an antiseptic, and a vasodilator. It would take several more articles just to begin to give a brief overview of the physiological consequences of the ingestion of ethyl alcohol. In terms of practical knowledge, however, you absolutely need to know that:

Note: You must weigh at least 240 pounds and drink only one drink per hour to remain “even.” If you weigh less and/ or drink more, alcohol will accumulate in your system since the elimination rate is only .015/hour.

- You become impaired long before you get drunk.

- Almost all of the information that you have about alcohol you have gotten from unscientific sources and personal experiences which have not been critically evaluated.

- Given the above, you must consider yourself to be at risk in any potential drinking and driving situation.

What can you do? Several departments now hire a bus to transport members to and from social events. This limits risk and liability. Integrating alcohol education into your training curriculum is an idea which sometimes elicits groans, but if done correctly, leaves people asking for more. I have taught such programs to military reserve units the first thing on a Saturday morning. Talk about a tough audience! But, like firefighters, these people have a positive attitude towards the delivery of service. And they could quickly see that this information was going to enhance their ability to perform their mission. It was also going to help prevent personal loss.

Most people, and firefighters especially, do not want to be a menace. They really do want to do the responsible thing in most situations. If you can capitalize on this positive predisposition and present the information in a beneficial rather than a judgemental manner, you are likely to get a good return on the time invested in preparing the program. We spend a lot of training time informing firefighters about the technical specifications of so much of the equipment they use. However, the most essential part of the fire suppression effort, the firefighter himself, has technical specifications and tolerance levels as well. Alcohol is just another of the many diverse areas that an effective and safe firefighter needs to know about to do his job.