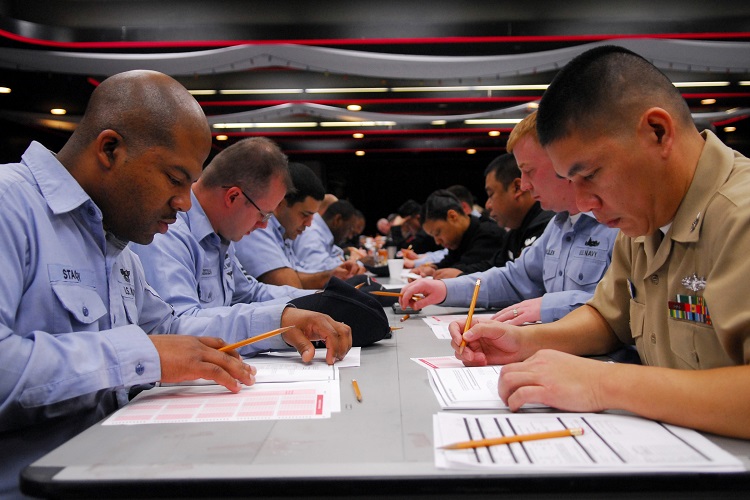

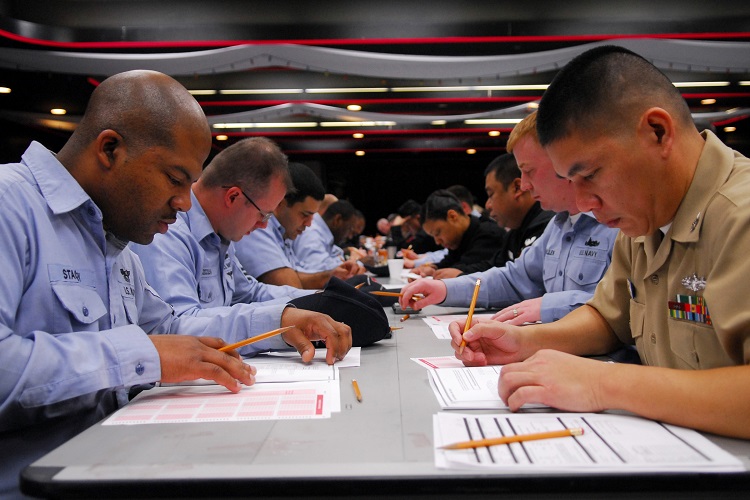

First class petty officers take the 2009 chief petty officer advancement exam at Fleet Activities Yokosuka. (U.S. Navy photo by Charles Oki/Released.)

By Daniel J. Neal

In mid-April 2016, I competed in my department for the rank of battalion chief. The test was very comprehensive and was formatted as a “Day-in-the-Life.” This format simulates an actual portion of the work day of a battalion chief. Over a period of four to five hours, the candidates are presented with phone calls, role-playing, paperwork, and emergency incidents. Each event is timed and scripted to occur at the same time and in the same way for each candidate.

To be successful, a candidate must not only know what to do, but demonstrate how to do it. That could mean counseling a subordinate officer, managing a structure fire, or documenting a sexual harassment complaint.

As I prepared, the following nine steps became apparent.

1. Start early. It is important to provide yourself plenty of time to read, review, practice, and adjust your study plan. Therefore, start studying and preparing several months ahead of time. To prepare for this process, I began studying more than four months before the test. I began by creating a folder on my personal thumb drive. This folder contained all of the operational manuals, human resources policies, and other material that might be on the test. I also downloaded articles on promotional preparation, command scenarios, advice from mentors, my application, and the job announcement for the position. This folder became my repository for anything in preparation for the promotional test.

2. Talk to other battalion chiefs. Before you can begin preparing, you need to know what to prepare for. Although you may know about the type of promotional process, investigate the promotional process. I spoke to several battalion chiefs in my department and I asked about the format of the test. I asked how they prepared and what they would do differently if they took the test again. I also asked what advice they had for me to be successful.

People enjoy talking about their testing experiences. As they talked, I took detailed notes. Some battalion chiefs even provided me with their personal test results. This was invaluable; it allowed a glimpse into the scenarios and events of their test. It also showed what information had been tested on previously. Every chief also pointed out, “What have been the current issues that the department has faced?” These could be potential issues or scenarios. For example, my department often struggled with basement fire tactics. This could be a potential emergency incident. This type of issue would definitely be one to practice if it has the potential to be on the test.

3. Based on your research, make up a study plan. After talking to several battalion chiefs (who passed the test, since they were now battalion chiefs), I began to develop a study plan. This plan laid out the next four months of benchmarks so I could cover the material and prepare for a “Day-in-the-Life.” It included deadlines to complete reading operations manuals, to begin running command scenarios, and to meet with study groups to test my preparation. If you do not plan, you plan to fail. Everyone has a busy life, and everyone has the same amount of time. Dedicate time every day to studying. Some days, I would spend three to four hours studying manuals. Other days, I would have 15 minutes to review some human resources policies. After a few weeks, studying for the process became part of a normal day.

4. Review your department’s response and administrative manuals. The battalion chiefs’ process for which I prepared encompassed more than 11 operational manuals, the human resources manual, and the department’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) manual. This was easily several hundred pages of information. Remember, you are eating an elephant. Small bites will win in the long run. I would read the manuals with a critical eye as I looked for important information and benchmarks. For example, in the command manual, I focused on establishing and transferring command. In the rural water operations manual, I focused on the roles of each pumper to set up a water supply. I would mark these pages for future reference. Carrying all of these manuals around could be cumbersome. I sent the electronic copies to a local print shop to print hard copies. Then, I could take a manual (or two) with me at the station or home. You could also load all of your resources on an electronic device for ease.

5. Make study guides that summarize actions to critical issues and incidents. Many people do not know how to study properly. To prepare for a test, they often think they should read (and re-read) the books. This is the first step, but the manuals contain a lot of information that you should already know. As you marked critical benchmarks in each manual or policy, start making study guides.

I created two study guides that were each more than 20 pages in length. The first focused on emergency incidents. Formatted like a playwright’s script, it laid out proper radio language for nearly every conceivable emergency incident. It also focused on the appropriate radio traffic for a battalion chief. For example, it laid out the correct way to take command, question the size-up of a first-arriving engine company, and establish a division on a high-rise fire.

The second study guide focused on how to handle administrative issues. This study guide took the long list of policies and SOPs and boiled them down to an issue followed by a list of the appropriate responses to that issue. For example, it described how to address notification that an engine was involved in an accident while responding to an incident. The appropriate actions include ensuring another unit is responding to the initial alarm, notifying the fleet department, directing the officer to complete accident paperwork, and notifying the deputy chief of the incident. This study guide covered a wide gamut of issues, from handling a harassment claim, to completing monthly productivity reporting, and to handling a firefighter’s request for outside employment.

Making the study guides is an important step, but not the last one. The mere process of making these study guides will begin to commit the information to memory. As the time of the promotional test got closer, I began to review the study guides several times each day. Reading about the first engine’s botched size-up or personnel issue, I would recite (in my head) the appropriate battalion chief response. Within a week of the test, I nearly memorized the study guides.

RELATED: Ricci on the Promotional Exam ‖ Humpday Hangout: Preparing for a Promotional Process/Exam ‖ Prziborowski: Prepare for Your Promotion Now!

6. Conduct varied and multiple command scenarios. One of my mentor’s continually crows, “It is not what you know in these processes, but your ability to apply it.” Nothing is more true than when you are preparing for the command scenarios. The “Day-in-the-Life” emergency simulations are conducted over a portable radio in front of a simulation screen of an emergency incident. In a separate control room, multiple role-players act as different apparatus responding to the incident. Even for the most experienced tactician, it is stressful to sit in front of a projected simulation image and command an incident while being evaluated.

Again, preparation is the key. Take every opportunity to conduct simulations for practice. At my station, the on-shift lieutenant and crew spent many hours providing me with every conceivable scenario. We used our training room and projected any applicable image from the Internet. Then, we used our portable radios on a training channel, and I commanded the incident. I completed a command board, assigned units, and asked for CAN (conditions, actions, needs) reports. When the scenario was over, everyone provided feedback—even the newest firefighter. Repetition and variety were the key. I was able to practice high-rise fires, basement fires, and mass casualty incidents. These scenarios required me to demonstrate my knowledge of the manuals.

There are two other important ways to prepare for scenarios. First, know how to complete a command board, and use it. In my department, captains do not usually complete command boards. Therefore, this is not inherent knowledge at that level. By working with battalion chiefs, I was able to learn the correct way to complete a command board. This was important since it was a graded portion of the “Day-in-the-Life” test.

Second, get as much practice as possible running scenarios. I partially accomplished this by recertifying my Blue Card Command certification. Although the Blue Card language varied from my own department, the “sets and reps” was excellent practice. This was three days of talking on the radio, doing size-ups, taking command, and providing situation updates. I took my own command board with me and bolstered my practice even more. When I returned home, I was already comfortable when presented with a simulation. Then, I could focus on honing my command skills with the local flavor.

7. Anticipate a staffing problem and personnel problem. Every department has to address staffing, but every department addresses it differently. As a battalion chief, staffing is an issue that arises often. Also, apparatus cannot perform our primary mission without staffing. To prepare for a staffing problem, I looked at my department’s real staffing rosters. Often reviewing rosters several days ahead, I would look for vacancies and try to identify how it would be filled by the staffing office. For example, a paramedic on the C-shift called out sick. Is there an extra paramedic on the roster for that day, or will someone be called in on overtime? Another common example would be an apparatus driver needing to be replaced because of an illness or injury. Where are other the drivers on the roster? Is there a firefighter who can fill that role? This was an easy way to practice the handling staffing problems.

[Another responsibility of a battalion chief (or any officer) is to address personnel problems.]

8. Have a plan when your “Day” starts, and stick to it. It may sound strange to have a plan when you enter a promotional test, but it is essential. Throughout my preparation, I learned that my “day” would have many issues, emergency incidents, and important items to document. I needed to have a structure to methodically address each item.

As I was led into the room, it was apparent that the process was intended to challenge the candidates. An emergency incident could be dispatched at any time. With multiple suppression pieces responding, I needed to rapidly capture these units before I was led to the simulation room, where my command board awaited. To ensure I could capture these units, I dedicated a piece of paper on the edge of my desk. I wrote a generic apparatus response package that I could easily jot down the unit numbers when a simulation was dispatched. From my research, the battalion chiefs advised, “If you don’t capture the units by the second announcement, you will never catch up.”

After listing potential apparatus packages, the second item I prepared was “the pass-on.” In my department, we live and die by our daily formatted e-mail pass-ons. This email lists the apparatus, personnel, emergency incidents with a brief description, information from station visits, pertinent items, and any action items. This document keeps operations consistent and all officers (and chief officers) informed on daily operations. As I formatted my pass-on, I prepared to enter issues and responses as they occurred. Then, I would be less apt to forget an important item.

Next, I prepared to contact every station officer in my battalion during the “day” for a status check. Using an interoffice phone, a candidate could contact nearly any role-player by dialing one extension. The operator would then provide the role-player from the control room. Although several issues arose without contacting the stations, several battalion chiefs stated that they received additional information from contacting each station. For example, an apparatus issue (i.e., out of service) or scheduling conflict could become apparent. I prepared the following four questions to ask each station officer:

- Are all of your personnel in and ready for today?

- What do they have going on for the day?

- Do you have any problems, or is there anything I can help you with?

- Can you make sure you and your personnel are safe today?

9. When it is over, walk away feeling good about it. Despite how you score, you want to walk out of the battalion chief’s promotional test with a sense of satisfaction, that you feel you prepared yourself as well as possible. You do not want to wish you had more time or memorized A, B, or C. With proper time investment and time management, you should have prepared to the best of your ability. Then, despite the results or ranking, you will be satisfied with your performance. You may not have scored Number One, but you did your best; that is what matters.

After you have recovered from the test, it is time to pay it backward and forward. First, thank everyone who spent time helping you prepare. Send them a “thank you” card or e-mail. Drop off a small gift at their house or office. I bought one chief a case of beer since he spent several days helping me prepare. Another chief loves Dunkin Donuts coffee, so I bought him a gift card. Every chief who helped me got a personal message about what he did that helped me in the process.

With the battalion chiefs’ promotional process completed, the department is preparing for a captain’s process. With all the tips and tricks, I began to help the current lieutenants as they prepared for the next process. Using the files on my thumb drive, it was easy to come up with administrative and role-playing scenarios; I even shared my two study guides with many of them. Of course, it is the process of studying and preparing that is the true benefit. Everyone begins to become better officers even before they complete the promotional process. My mother (a retired teacher) always spoke to this point about learning: “It is not the end point that is the benefit, but the process.”

Daniel J. Neal, PhD, EFO, is a captain with the Loudoun County (VA) Department of Fire and Rescue. He ranked #1 on the department’s battalion chief’s list and hopes to get promoted to the position soon.

Daniel J. Neal, PhD, EFO, is a captain with the Loudoun County (VA) Department of Fire and Rescue. He ranked #1 on the department’s battalion chief’s list and hopes to get promoted to the position soon.