Multiple-Choice Questions for Tests

features

Understanding how multiplechoice test questions should be written is helpful not only to the test developer, but also to those taking such tests. Knowledge of how multiple-choice questions should be written can help the testtaker to select the proper answer.

Teaching is an important part of fire service training

Consider the last class that you taught. Perhaps it was for local company drill, or for preparation for an important exam, or for department-wide training. Inevitably, all instructors, volunteer, experienced or inexperienced, must deal with the preparation of an exam. Now what?

“Well, no sweat, I’ll just write down some questions with a few answers, pass them out and that will be the end of that.”

But it wasn’t quite that simple, was it? Were there complaints about wording? Was there haggling over answers? Did the participants fail to understand the questions or accuse you of writing vague questions?

In this article, we will take a look at what can go wrong when we prepare multiple-choice tests and, more importantly, what we can do about it. We won’t become experts, but like learning fire suppression, with a little study and a lot of on-the-job training, we can accomplish the task.

No test is perfect

First, let’s get one thing straight. The perfect multiple-choice test has probably not yet been written. PhDs in test development spend huge amounts of time and energy to prepare multiplechoice tests which inevitably require revision. On the other hand, any thoughtful attempt to write clear and unambiguous questions is likely to bear fruit.

The first step to successful multiplechoice test writing is to identify yourself as suffering from one or more of the following illnesses:

- “They know what I mean” syndrome

- “It ain’t no big deal” syndrome

- “Anybody can write those things” syndrome

- “I can’t do that stuff’ syndrome

The individual suffering from the not necessarily fatal illness of the “they know what I mean” syndrome supposes that it really isn’t necessary to use clear and precise wording in the construction of multiple-choice questions. After all, “they know what I mean.” But it is not until after the test papers are handed back that the symptoms start, usually headache and nausea from students complaining about unclear questions, trick questions, poor wording and unreasonable difficulty. The cure? Careful scrutiny of questions by the writer and by others who may able to offer constructive criticism.

Avoid little mistakes

Sufferers from the “it ain’t no big deal” syndrome refuse to accept the fact that a few “little mistakes” in a multiple-choice test won’t make any difference in the outcome or the consequences of the test. They forget that individuals who are test-takers always have something at stake, whether it be ego on the one hand or a promotion meaning increased recognition with financial and career advancement on the other. The test-takers scrutinize questions minutely for specific wording and subtle meanings. The unfortunate individuals suffering from this syndrome often find themselves at the losing end of an unnecessarily ugly argument—or a lawsuit. Cure: Recognition that test-takers may place more importance on the outcome of a test than was anticipated.

The “anybody can write those things” syndrome is one of the most serious and perhaps widespread illnesses among test-writers. They are deluded by the fact that they have personally taken numerous multiple-choice tests and “it can’t be that difficult to write one.” In more severe cases, once their test is prepared, their response is “see, it wasn’t so bad.” But it is. Students grumble and superiors wince when they read the test. Cure: The willingness to admit that perhaps there is more to “simple test question-writing than meets the eye.

The “I can’t do that stuff” syndrome is marked by a tendency to cop out. The tendency here is to look at the maze of rules, suggestions, recommendations for improvement of multiple-choice questions and say, “I can’t do that stuff.” But tests don’t get better by themselves. Cure: Read on and see that it doesn’t take a magician to improve the quality of your test items.

There are two major types of multiple-choice items: the one best response type and the multiple true-false type. The traditional, and most frequently used, item is the one best response type in which there is a stem (e.g., a statement, question, situation, chart, graph or picture) followed by a series of five suggested answers or completions. The suggested answers (or completions) other than the correct choice are called distractors.

A series of five choices (one correct answer plus four distractors) is preferred to a series of four choices. In the fourchoice item, an individual knowing nothing about the subject matter has a 25 percent chance of getting the item right. The five choice item decreases his chances to 20 percent on the basis of random guessing.

One best response

The one best response item emphasizes that the examinee select the best response from those offered. The item has a comparative sense: one procedure is best out of the five choices, one piece of equipment is the best of those at hand, one value is the most accurate in response to a required calculation, one aspect in foreground size-up is most critical at a given point given other variables. In the fire service, contrasts are seldom sharply defined as black and white, but are apt to be varying shades of gray. In answering these questions, therefore, the examinee is instructed to look for the best or most appropriate choice and to discard others that may appear plausible but are in fact less applicable.

Here is an example of the one best response type question:

The most important aspect in initial size-up at a fire scene is:

- Establishment of water supply.

- allocation of personnel.

- determination of life hazard.

- positioning of existing equipment.

- protection of exposures.

This example illustrates the onebest-response type. While some answers may be wrong and some right, the question asks the examinee to pick the answer which is clearly best.

Multiple true-false type

The second type of multiple choice item is the multiple true-false type. Multiple true-false items consist of a stem followed by three, four, or five true or false statements, which are followed by five options, each designated by a letter. The stem may be in the form of a question, a statement, a description of a fire scene or set of circumstances. When properly written, the multiple true-false item tests in depth the examinee’s knowledge or understanding of several aspects of a process or procedure. It is imperative that each of the statements or completions offered as possibilities be unequivocally true or false, in contrast to the type of item in which partially correct alternatives may be used as distractors (the one-best-response type). This type of question should be written so that no two alternatives are mutually exclusive, since the examinee is expected to consider the possibility that all of the choices may be correct.

Here is an example of the multiple true-false type question:

Which of the following conditions are characteristic of the “free-burning” phase in a confined structural fire?

- Oxygen content 20 percent of atmosphere

- Major chance for smoke explosion

- Limited but increasing smoke production

- Rapid heat generation

- I only

- II and III only

- II and IV only

- * III and IV only

- I, II, III, IV

Note the difference between the multiple true-false question above and the one-best-response type. In the example above, the statements (Roman numerals I – IV) are each totally true or totally false. Each alternative in the one-best-response type may be partially true.

Multiple-choice anatomy

Just like an understanding of the individual parts of a pump are necessary to operate, troubleshoot and derive the most benefit from it during fireground operations, so too it is necessary to learn the parts of a multiple-choice question to get it to do what you want it to do. Let’s look at a simple example:

STEM —

Fires involving flammable liquids, gases, greases, and similar materials are classified as:

OPTIONS

A. Class A

Distractor

B. Class B

Correct Response

C. Class C

D. Class D

E. Class E

Distractors

This item could just as easily have been written in question form like this:

Which of the following classifications is correct for a fire involving flammable liquids, gases, greases and similar materials?

- Class A

- * Class B

- Class C

- Class D

- Class E

Which type to use?

Some item ideas can be expressed more simply and clearly in the incomplete statement style of question (our first example). On the other hand, some items seem to require direct question stems for most effective expression. Use the style that seems most appropriate for the particular item at hand. If, in a given instance, it seems to make little or no difference which type is used, choose the style that you can generally handle most effectively. There is no evidence that either is inherently superior to the other.

Those who have not had experience in writing multiple-choice items may find that at the beginning, they will tend to produce fewer technically weak items when they try to use direct questions rather than when they use the incomplete statement approach. It is often difficult to arrange qualifying phrases or words to produce a perfectly clear statement. In addition, because of its specificity, the direct question causes the item writer to produce more specific responses.

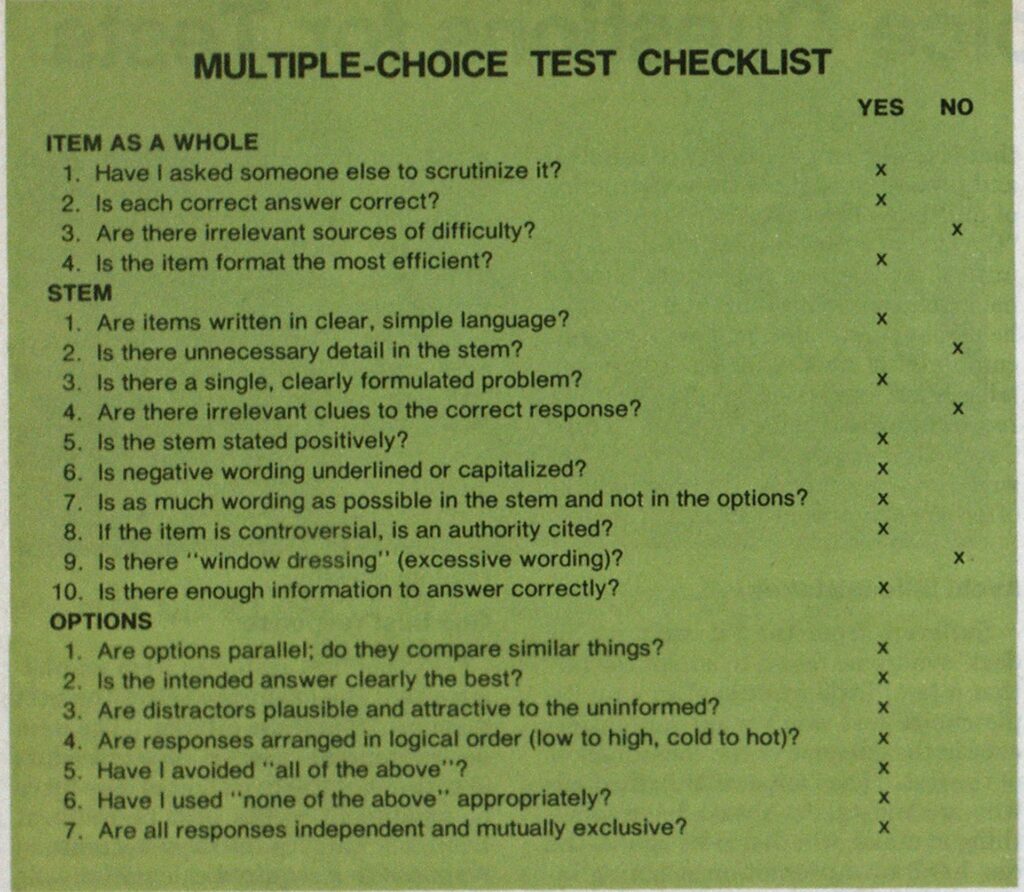

Now that we understand the anatomy of a multiple-choice item, let’s discuss some helpful hints regarding the item as a whole, the stem, and the options.

Review of questions

Whether we are writing questions for local station use or for department-wide, statewide or nationwide tests, the common denominator is the same always: Is this the best test that I can give with the resources at hand? Are the questions clear and reasonable?

The first step in arriving at an answer to these questions is to expose your items to editorial scrutiny. The word editorial” in this suggestion refers to content even more than to adequacy with respect to grammar, diction or spelling. Ask another person or group of persons to review your questions. Ask them to red-ink them and give candid comments and constructive criticism. And remember, you are asking them to help you. Accept their criticism graciously and gratefully. They are helping you to view your questions from a different perspective. They are doing you a service.

Specifically, what is it that you are asking this “group of experts” to review? First, ask them to check the correctness of the “correct” answer. While it is a minor embarrassment for the writer to have a colleague point out that an item has been keyed incorrectly, it is far more embarrassing to have examinees bring such a fact to a writer’s attention.

Second, ask them to estimate the appropriateness of the difficulty of each item. Someone who has had experience with examinees similar to those for whom an item is intended often will be able to characterize a proposed item as ridiculously easy or extraordinarily difficult.

Seek advice on wording

Third, ask for suggestions for better wording. Precision of language and clarity of communication are vitally important to good items. An unbiased critic may find it easier than the original writer to improve the language in an item.

Fourth, ask for suggestions for better distractors. No writer has a monopoly on good distractors. Since good distractors are often the common misconceptions that prevail among examinees, a colleague might be able to offer some distractors that are more alluring and discriminating.

Finally, ask for an appraisal of the item’s significance. An item writer will sometimes, under pressure to fulfill a commitment or complete a test for his class, yield to temptation and write one or more items that are easy to write rather than of true significance. Frequently, these will measure inconsequential facts or unimportant relationships. A reviewer can identify these items and thus act as an external conscience for the item writer. The resulting test should be fairer to the examinees and a more meaningful evaluation instrument.

Have a central problem

In viewing your own completed items, ask yourself if you have based each item on a single central problem. For instance, consider the following troublesome item:

POOR: Air in contact with metal ceilings will:

- be heated by conduction.

- cause emission of flammable vapors from exposed material.

- facilitate fire spread by radiation.

- provide oxygen for a smoke explosion.

- have a higher carbon monoxide content.

The above item is not based on a single central problem. In reality, this item is concerned with five different problems. The examinee is looking for a single problem and he becomes confused and uncertain about the main point of the question. What we have here is a series of true-false statements where the question loses the central advantage of the multiple-choice form. The examinee is not really required to choose the best of a number of alternative choices to a single problem, but rather to decide which of a number of independent true-false statements is more true than others. This is a difficult and confusing task at best.

Clarity of task in stem

The task set forth in the stem of the item should be so clear that it is understood without reading the alternatives! In fact, a good check on the clarity and completeness of a multiple-choice stem is to cover the alternatives and determine whether it could be answered without the choices. Consider the following items:

DON’T:

- Use more words than are necessary to ask the question

- Use details when they are not necessary

- Ask two problems in one

DO:

- Keep it simple

- Use detail only when it relates to an important outcome

- Pose only one problem per item

Review of numerous fire service multiple-choice tests reveals that greater than 50 percent of the technical errors could have been eliminated if the few do’s and don’t’s above had been observed. Try it yourself!

POOR: Ventilation

- should be performed before water is applied to the fire.

- should be accomplished by truck company personnel.

- should be accomplished upwind of the fire.

- should be accomplished with regard to exposure hazards.

- should be performed by opening the roof at the point farthest from the fire.

IMPROVED: What is the main purpose of ventilation?

- It provides a means of entry for personnel.

- It controls the circulation of heat, smoke and gases.

- It provides openings for fire streams.

- It decreases the amount of fuel for combustion.

- It provides an alternative means of escape for occupants.

The “poor” item above is no more than a collection of true-false statements with a common stem. The problem presented in the “improved” version is clear enough to provide a series of possible answers from which to choose. Note also, in the second version, that a single problem is presented in the stem. Including more than one problem usually adds to the complexity of the wording and reduces the diagnostic value of the item. When a student or examinee fails such an item, there is no way to determine which of the problems prevented him from responding correctly.

Avoid irrelevant difficulties

Another suggestion in reviewing your own items is to check to see if you have avoided irrelevant sources of difficulty. Just as it is possible to incorporate clues to a correct response, it is also possible to unintentionally place obstacles in the path of the examinee. Frequently, reasoning problems in hydraulics or fire streams are answered incorrectly by examinees who reasoned correctly but who have slipped in their computations. This item was designed to measure the examinee’s ability to manipulate the variables of flow and hose diameter to arrive at an appropriate friction loss.

POOR: If 463 gpm is flowing from a nozzle, the friction loss per 100 feet of 3-inch fire hose would be:

- 15 psi.

- 17 psi.

- * 19 psi.

- 21 psi.

- 23 psi.

IMPROVED: (Modified to evaluate reasoning and not mathematical ability):

If 500 gpm is flowing from a nozzle, the friction loss per hundred feet of 3inch fire hose would be:

- 5 psi.

- 10 psi.

- 15 psi

- 20 psi.

- 25 psi.

Use efficient item format

In preparing your test, use an efficient item format. Alternatives should be listed on separate lines, directly under one another. This makes alternatives easy to read and compare. The use of letters in front of alternatives is preferable to using numbers. This avoids possible confusion when numerical answers are used in an item.

When writing the item, use the normal rules of grammar. If the stem of the item is a question, each alternative should begin with a capital letter and end with a period of other terminal punctuation mark if the distractor is a complete sentence. The period should be omitted with numerical answers to avoid confusing them with decimal points. When the stem is an incomplete statement, each alternative should begin with a lower case letter. No terminal punctuation mark is used at the end of incomplete sentences.

Items should be written in clear and simple language with the vocabulary kept as simple as possible. Don’t try to impress your reader with your vocabulary. The production of good test items is an exacting task. Few other words are read with such critical attention to implied and expressed meanings as those used in test items. Unlike a book or article, an isolated multiple-choice item has no context. Each item must be explicitly clear in and of itself. Difficult and unnecessary technical vocabulary should be avoided. Sentence structure should be as simple as possible. Complex sentences should be broken up. Important elements should appear early in the statement of an item, with qualifications and explanations following.

Omit unnecessary detail

Avoid unessential specificity in the stem or responses. The superior value of general knowledge over specific knowledge has long been recognized and should be reflected in tests whenever possible. Why test insignificant detail? Such detail is a powerful incentive to rote learning and may unfairly penalize an examinee whose educational goals are more mature and whose study habits are not aimed at insignificant detail. These questions fall into the “who cares” category. Here is an example:

POOR: The temperature at which an aluminum aerial ladder loses 50 percent of its tensile strength is:

- 230°F

- 375°F

- * 450°F

- 525°F

- 675°F

The above question is too detailed for general purposes. It does not test a general concept which may be applied in a variety of situations. Most of all, it is not usable knowledge necessary for competency in a fire fighter’s daily performance of his function.

Eliminate irrelevant clues

An additional suggestion in the preparation of a multiple-choice test is to review your questions in an attempt to eliminate irrelevant clues to the correct response. Clues may make the item easier as a whole or may even change the basis upon which the item discriminates. If all examinees notice the clue and all respond correctly on the basis of it, the item becomes nondiscriminating and hence, useless. If a number of examinees who normally would not be able to choose the correct response notice the clue and respond correctly on the basis of it, the clue seriously weakens the item. Here are several major categories of clues to avoid or points which should be stressed:

- Avoid similarity of wording in both the stem and the correct answer.

- Avoid stating the correct answer in textbook language or stereotyped phraseology.

- Avoid stating the correct answer in greater detail than the other alternatives.

- Avoid including absolute terms (always, never, all, none) in the detractors.

- Avoid including two responses that are all-inclusive.

- Avoid including two responses that have the same meaning.

Do make all alternatives grammatically consistent with the stem of the item and parallel in form.

State question positively

As you progress in your examination of items you have written, make sure that you have stated the stem of each item in a positive form wherever possible. A positively phrased item tends to measure more important learning outcomes than a negatively stated item. This is because knowing such things as the best method of extinguishment or the most important variable to consider in size-up of a fire situation has greater educational significance than knowing the poorest method or the least important variable. The use of negatively stated items all too frequently results from the ease with which such items can be constructed rather than from the importance of the learning outcomes measured.

POOR: Which of the following methods of extinguishment is the least effective for a fire involving an uncontained gasoline spill?

- (A) Shut off supply

- (B) Apply dry chemical

- (C) Apply carbon dioxide

- (D) Dilute with water

- (E) Apply halogenated hydrocarbons

The above example could be improved by increasing the specificity of the stem and by changing “least” to “most.” Being able to identify answers which do not apply provides no assurance that the examinee possesses the desired knowledge.

Negative emphasis

There are instances when the use of negative wording is basic to the measurement of an important learning outcome. Any potentially dangerous situation may require a negative emphasis. Almost any set of rules or procedures in the fire service places some emphasis on practices to be avoided. When negative wording is used in the stem of an item, it should be emphasized by underlining or capital letters and by being placed near the end of the statement.

GOOD: All of the following are desirable ventilation practices EXCEPT:

- use of mechanical smoke ejectors.

- use of natural openings.

- use of fog streams.

- opening a roof directly over the fire.

- * horizontal ventilation from the windward side first.

The above question illustrates appropriate use of a question with a negative emphasis. Don’t overuse it on a test.

Put as much of the wording as possible in the stem of the item. This will be helpful for several reasons. First, you will avoid repeating the same material over again in each of the alternatives. By moving all common wording to the stem, it is usually possible to further clarify the problem and to reduce the time required to read the alternatives. Note the improvement in the following item when this rule is followed:

POOR: Tools that have wooden handles should be:

- lightly sanded and coated with a light varnish.

- lightly sanded and coated with a water-based paint.

- lightly sanded and coated with linseed oil.

- lightly sanded and coated with polyurethane.

- lightly sanded and coated with light oil.

IMPROVED: Tools that have wooden handles should be lightly sanded and coated with:

- light varnish.

- water-based paint.

- linseed oil.

- polyurethane.

- light oil.

(This is an example of a question for which the correct answer depends on local department policy. “Sanding only” is another alternative followed by some departments.)

The improved version puts as much of the wording as possible into the stem. In many cases, it is not simply a matter of moving the common words to the stem, but of rewording the item.

Avoid window dressing

A common problem in writing multiple-choice items is the use of excessive window dressing. Oftentimes we inadvertently include material in the stem which is irrelevant to the real problem posed in the item. The excess wordiness can confuse the examinee and waste his time in reading nonpertinent information. Remember, economy of wording and clarity of expression are important goals in item writing. Consider the following examples:

POOR: There are four objectives of any fire service organization but only one of these is concerned with forcible entry. Which one of the following is the objective of forcible entry?

- Prevention of fire hazards

- Saving lives and reducing property damage

- Confining fire to place of origin

- Extinguishment of the fire

- Determination of fire origin

IMPROVED: Which of the following items is a primary objective of forcible entry?

- Prevention of fire hazards

- Saving lives and reducing property damageConfining the fire to the place of origin

- Extinguishment of the fire

- Determination of the fire origin

The improved version eliminates unnecessary wording, poses a clearly stated problem, and decreases the possibility of confusion.

Include enough information

Finally, in reviewing the stem of each item, make sure that you have included all the qualifications needed to provide a reasonable basis for response selection. Frequently an item writer does not state explicitly the qualifications that exist implicitly in his own thinking about a topic. He forgets that a different individual, at another time, needs to have these qualifications specifically stated. In the following examples, note how differently the question can be interpreted with proper qualification:

POOR: Which of the following nozzles is designed for maximum effectiveness in a single-family dwelling fire?

- hand line straight tip

- master stream fog

- hand line fog

- master stream straight tip

- cellar nozzle

This example is vague due to lack of proper qualification.

IMPROVED: Which of the following nozzles is designed for maximum effectiveness on an attack line in a one-story, single-family brick and frame dwelling with a small fire confined to one room?

- hand line straight tip

- master stream fog

- hand line fog

- master stream straight tip

- cellar nozzle

The improved example states the question more clearly by adding proper qualifiers.

Sources of distractors

Next, let’s focus upon the options for the item, the answers and incorrect responses. Don’t forget that the options are as important as your statement of the problem in the stem. Select yourdistractors—the wrong answers—with care. Incorrectness should not be the sole criterion!

Here are some sources of good distractors.

- Common misconceptions and common errors.

- A statement which is true but which doesn’t satisfy the requirements of the problem.

- A statement which is either too broad or too narrow for the requirements of the problem.

- A carefully worded incorrect statement that may sound plausible to the uninformed.

The distractors in a multiple-choice item should be so appealing to the candidate who lacks the knowledge called for in the item that he selects one of the distractors in preference to the correct answer. There are a number of things that can be done to increase the plausibility and attractiveness of distractors. These are summarized below:

- Use positive-sounding words, such as “accurate” and “important.”

- Make the distractors similar to the correct answer in both complexity and wording.

- Include the most common errors or misconceptions found in the examinee group.

- Avoid using alternatives which are opposites of each other. Each and every alternative should be plausible. Opposites are inconsistent with that idea, and examinees can eliminate them with limited information.

- Make your alternatives homogeneous. Don’t ask examinees to compare apples to oranges. In educational jargon, make your alternatives parallel.

- State your alternatives in the language of your examinees. This is not the place to try to flaunt your vocabulary.

- It is OK to use stereotyped phrasing and scientific-sounding answers as extraneous clues in the distractors, but don’t overdo it. Remember that the point here is to produce good questions which discriminate well, not trick questions.

Common pitfall

One particularly common problem found in the option section of multiplechoice exams is the use (and abuse) of “all of the above” and “none of the above.” Avoid the use of “all of the above” and use “none of the above” with extreme caution. When a test-maker is having difficulty in locating a sufficient number of distractors, he frequently resorts to the use of these problemcausing options.

The inclusion of “all of the above” as an option makes it possible to answer the item on the basis of partial information. When the test-taker is asked to select only one answer, he can detect “all of the above” as the correct choice by simply noting that two of the alternatives are correct. He can also detect it as a wrong answer by noting that at least one of the alternatives is incorrect.

The use of “none of the above” obviously is not possible with the bestanswer type multiple-choice item since the alternatives vary in appropriateness. When used as the right answer in a correct-answer type item, this option may be measuring nothing more than the ability to detect incorrect answers.

Avoid overlap responses

Make your responses independent and mutually exclusive. Responses should not be interrelated in meaning. Sometimes a subset of two or three responses may cover an entire range of possibilities, so that one of them must necessarily be correct. Sometimes one response may include one or more of the other responses so that all the items in that subset must necessarily be false.

In the following illustration the first three responses cover the entire range of possibilities. The item is improved by making the responses independent.

POOR: As the gases in a confined room are heated, the

- pressure in the room increases.

- pressure in the room decreases.

- pressure in the room remains the same.

- gas in volume decreases.

- molecular motion decreases.

IMPROVED: (Responses made independent):

As the gases in a confined room are heated,the

- weight of the heated gas in creases.

- * pressure in the room increases.

- molecular motion decreases.

- volume of gas increases.

- partial pressure of oxygen increases.

Here is another common example of responses which overlap each other.

POOR: An 1 1/2-inch hand line stream has a capacity of

- less than 20 gpm.

- less than 40 gpm.

- more than 40 gpm.

- more than 100 gpm.

The problem here is that this is, essentially, only a two-part item. If A is correct, B is also correct. If B is correct, C is correct. Responses B and C cover the entire range of possibilities. An alert examinee can immediately eliminate A and D from consideration. The item can be improved in a number of ways that would serve to make the responses completely independent of each other. A simple approach would be the following:

IMPROVED: An 1 1/2-inch hand line stream has a capacity of

- less than 20 gpm.

- between 20 and 39 gpm.

- * between 40 and 125 gpm.

- greater than 125 gpm.

Few other organizations have such an important teaching mission to fulfill. Instruction and evaluation in the fire service is the key to more effective personnel and ideas. Widespread use of multiple-choice testing in the fire service demands that those of us who use this technique should know more about its application.

Any energy you expend in preparing a better multiple-choice test will make you a better test-giver and a better test-taker. Good luck!