In moving or removing down firefighters, we as rescuers can spend a lot of time considering how we can do so using their harnesses. How can we manipulate them, strap them, and reinforce them to effect a faster, more secure drag? On the other hand, we often explore the dragging and pulling options we have with what is in our pockets. Whether it’s a quick strap or a mechanical advantage drag, we strive to make ourselves adept at swiftly putting these maneuvers into play, and with good reason. We must be able to transition quickly to the next “move” when the most simple rescue techniques will not work.

- Personal Harness Use for Firefighter Rescue

- Basic SCBA Conversions for RIT Assist

- Training Minutes: Personal Harness for Firefighter Removal

- Firefighter Training Video: Hasty Harness

Regarding the simple capabilities of our own integrated harnesses, if we understand what they can do for us, we can quickly put them into use for anything including gaining access to or egress from an area, complementing simple drags, or even multiplying the capability of drags and pulls. What can our two-point seat harnesses do for us? At their most elemental level, they are designed to bear the brunt of our own weight in a bailout. The rated straps that run under your legs and back up to the waist harness ensure that the part of your body that is the most capable of handling weight assumes the load (photo 1). In years past, some emergency harnesses were secured around the chest (photo 2). They produced the desired result, just as any chest wrap would, but were incredibly painful, and any prolonged tension on them became hazardous to the wearer. Where the intended harness placement comes into play for us as rescuers is in their natural ability to allow us to transfer the load of another onto our bodies in the area that is most capable of handling it.

(1) Photos by author.

(2)

Think about dragging a victim—pulling him backward using your arms to hold him up and your legs to walk back. Your arms and upper body assume some of the weight, but your legs and trunk do the real work. Anyone who has dragged or pulled a victim during training or at an incident will tell you that the smaller muscles of your arms, back, and shoulders will tire more easily than those of your legs and core. In a way, your assisting muscles are a necessary intermediary for the bulk of the work. You must have some means of grabbing and securing the victim. Any strapping that you introduce (short of any mechanical advantage) is a medium between the load dragged and your maximum “load manager.” In a way, these mediums can take away from your ability to exert the most brute force on a load. Think of forcing the front door to a dwelling through a screen door. You could do it that way, but you’d rather get right at the door. Caution: Before considering the following manuevers, understand that you should only unclip or otherwise compromise your own harness in the most extreme circumstances—where expediting the removal could save a victim’s life or your own.

Clipping In

To ensure that the largest portion of the load you intend to drag is transferred directly onto the area most capable of handling it, you can clip your harness into the load. If the victim is a civilian, you must wrap the victim with something and then clip that into your harness. If the victim is a firefighter, you can attach his drag rescue device (DRD) to his own harness and then clip your own two-point harness into that. In photo 3, the arrows indicate where the DRD is attached to the victim’s harness (top arrow) and where the rescuer has clipped in (bottom arrow). You can also use the dedicated drag loop from the SCBA, the DRD alone, any number of ways. One of the most valuable advantages to rescuing in this fashion is that it requires no additional strapping or wrapping. You only use what is issued. You want to put the largest portion of the load onto the two-point harness first and foremost and then remove the victim. This is not to say that the arms and the upper body are out of the picture. You still use them to secure, pull, and stabilize, but they have been relegated to secondary assistance where they belong.

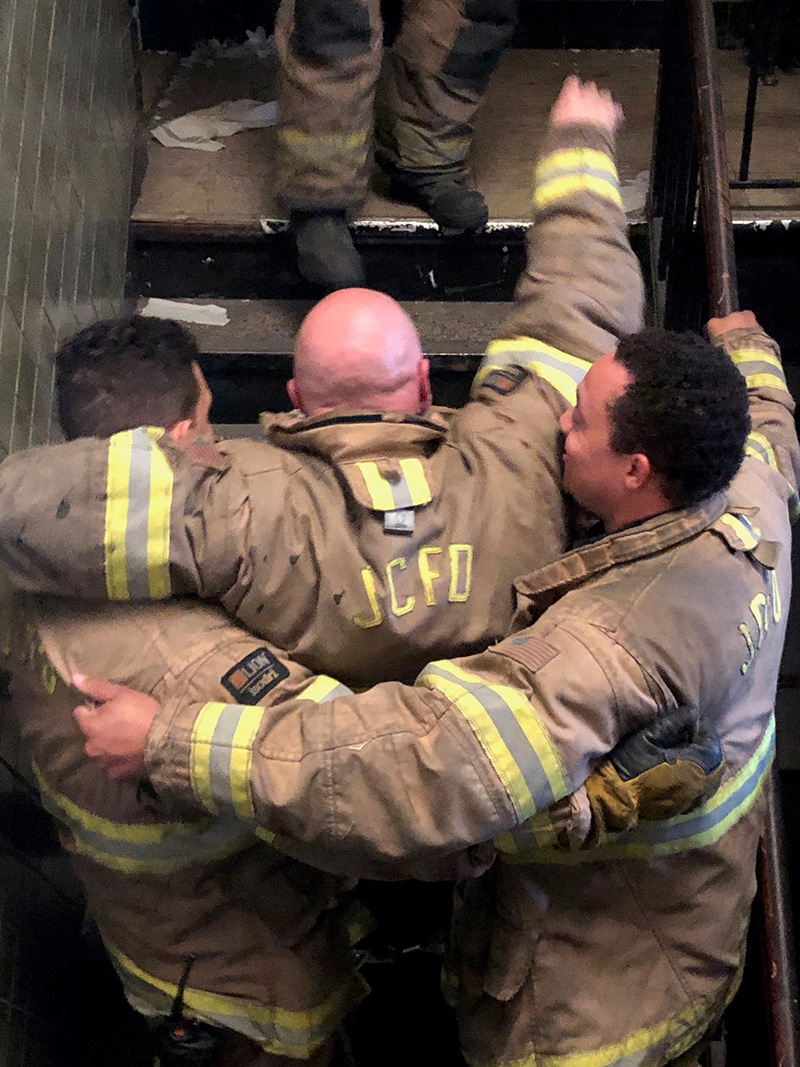

An area where this type of maneuver can pay big dividends is getting a down victim up stairs. By clipping the victim directly to your harness, you keep the load close to yourself and somewhat off the treads (photo 4). The rescuer can more easily move the victim up the stairs with the rescuer’s legs taking on most of the strain. In training, one rescuer was easily able to ascend stairs with a 235-pound victim.

(3)

Regarding positioning, note that if ascending stairs, it is good practice to jockey the victim’s SCBA around to the front side to keep it from snagging on the stairs. It is not essential, but it will help. Also, to enable your trunk to assume most of the load, you have to load your trunk. If dragging or ascending, standing straight upright will not be sufficient. That will just pull the load down on your waist while the leg straps remain slack and your thighs take no weight. In photo 4, the rescuer is clipped in and ascending the stairs; note how the rescuer’s legs remain slightly bent.

(4)

Fusing Two Harnesses

In the same way that you can make sure that your harness assumes the bulk of the weight in a “one-on-one” removal, if two rescuers are available and the rescue is a difficult or sizable one, the rescuing team can fuse their harnesses together to load share and make the removal more efficient. The same way you might set up self-equalizing anchors or load sharing in a rope rescue, you can “marry” your harnesses to load share. To do this, the two rescuers must face each other. They each fully extend their respective straps. Rescuer 1 clips the right clip of his harness to the left clip of rescuer 2 (arrows, photo 5). Rescuer 2 mimics the action. The result is a “harness” of sorts situated between the two rescuers.

(5)

Using the two-member fused harness could certainly come into play for a tough drag. If two members are trying to employ brute force to drag a sizable victim or two victims, they could assuredly fuse their harnesses together through the dragging medium (photo 6). This may assist a drag if the team is nearing exhaustion and the job has just been encountered; it happens.

(6)

However, the better option would be to use it for a seated carry removal. In this way, the rescuing firefighters can get the victim off the ground, seat him between the two of them in the harness, and walk out in tandem (circle, photo 7). This could be used for raising a victim up to a window or walking a victim up basement stairs.

(7)

To transition the victim from the ground to the fused harness, the rescuers need to take a knee on both sides of the victim but not directly over him. They should fuse their harnesses as described above, jockey the victim into position, and stand upward into a crouched position. If this maneuver is well practiced, walking a victim up stairs in this manner is considerably easier than trying to coordinate “push pulls.” Note that if the victim is facing down the stairs while being carried, you will not have to contend with his feet hitting the treads. However, if the rescuers stumble forward, the victim may stumble downward. Carrying the victim as shown in photo 8 may be better.

(8)

What if a stair/area is not wide enough for two rescuers and a victim? When fusing two harnesses together, it does not necessarily have to be done laterally as described above. The rescuers have the option of having the victim straddle the harness (photo 9). Removal can proceed as such. Again, rescuers would do well to continue to use their arms to stabilize both themselves and the victim, but with the bulk of the weight on their harnesses, the rescue upward/downward goes a lot more smoothly.

(9)

(10)

Additional Uses

In addition to simple drags and carries, a fused harness can be used so two firefighters can assume the load of another as a “last-ditch step.” Think of assisting an out-of-air firefighter up out of a basement window. If crews are waiting to help pull him up out of the window, two firefighters can wed their harnesses as described and the escaping firefighter can “step up” into it for that first boost up and out of a window (photo 10). In a pinch, the fused harness can be used to gain a little height in any scenario in which that is needed. After all other means are exhausted, you can use the harness to get a look into inaccessible loft/attic spaces, get a boost over a fence, reach for a blaring smoke detector, and so forth. Note that operating a line or tool while “standing” in the harness is dangerous; you should only do it if you have no other options.

. . .

Maximizing our harnesses’ capability not only makes us more efficient at rescue but empowers us to accomplish it when we are diminished. Drags and carries are relatively simple. We sometimes fail to anticipate that the drag or carry may not be needed as soon as we walk through the door. It could be very late in the fire when we could be quite physically drained. In some cases, our hands may lack the mere grip strength to hold onto a victim. In these instances, placing the load directly on ourselves enables us to complete the rescue. Two firefighters may be unable to force-pull a victim up the stairs, but they might have enough juice left in their legs to walk the victim up in a seat harness. Similarly, we may be operating in a “near vacant” with no loft access with confirmed significant loft extension. Waiting for a ladder is best, but quickly stepping up with a line may provide a quick knockout and make everyone safer. Taking the weight properly in these scenarios can allow us to work more swiftly and sometimes avert the need to set up a more intricate rescue. It is certainly within our power and worth our consideration.

ALEXANDER DEGNAN is an 18-year member of the Jersey City (NJ) Fire Department (JCFD), where he is the captain of #618 Squad Co. 4, a position he has held since 2015. Prior to his captain’s position, he was a 10-year firefighter with the JCFD’s #1013 Squad Co. 4.