MANAGEMENT OF PUBLIC FIRE EDUCATION

MANAGEMENT

A National Fire Academy Course SPOTLIGHT

A two-week course entitled Management of Public Education is being offered this year for the first time at the National Fire Academy. The course is designed for anyone in the fire service who is responsible for development, management and evaluation of public fire education in his community. Though many individuals taking the course do not hold a formal management position in their fire departments, as fire educators they must apply a number of management techniques to be successful in attacking their communities’ fire problems.

The course was developed last year by a team of fire educators from across the country. The specialized areas of need were determined by computer analysis of suggestions solicited from the past three years of graduates in the Fire Education Specialist course.

Because waiting lists for courses at NFA are long and many applicants are being turned away, an overview of the course follows with highlighted information that could be put to use by fire educators and fire administrators while they are waiting for admission.

Much of the class time for the course is devoted to group exercises in which students apply new techniques to work through hypothetical but realistic challenges. This article cannot provide the experience of group interaction under the expert guidance of NFA faculty, but fire educators can apply the following excerpted information presented in the course.

Educational Programming

In the first of six sections students are introduced to the concept of behavioral task analysis. In simpler terms, this is the process of planning how to teach a subject by first recognizing the major tasks and subtasks that members of the audience in a fire education program would be expected to perform. Task analysis helps the fire educator present a comprehensive program that does not omit subtle, but important, points. For example, a fire educator may not adequately prepare occupants of a building for a fire by simply telling them that they must sound the fire alarm. They must be able to locate an alarm station by recalling standard locations and be able to recognize the color and shape of the alarm. If a glass cover must be broken before a button is pushed, how will they break the glass? How hard should they push the button and for how long? Writing the steps down in order helps to avoid omitting an important part of the sequence.

With their knowledge of task analysis, groups of five students are instructed to design a fire education program for an audience in the hypothetical city. A number of fires have occurred in the city that the students must address in a program package. In designing the package the fire educators first analyze their target audience by its physical characteristics including age, sex, handicaps and stamina (ability to perform the behavior they will be taught). The audience’s educational background and prior understanding of fire prevention and survival are taken into consideration, as are their motivation to learn, their interests, attitudes and prejudices.

Finally the fire education needs of the audience are determined. The hypothetical audience has requested a fire extinguisher program and does in fact need instruction in this area, but the fire educators also attempt to determine needs that the target audience is not aware of. In the hypothetical case, EDITH (exit drills in the home) is identified as a target audience need. The fire educators work through the exercise, learning that once the profile of an audience is determined, an appropriate strategy for educating the audience about their fire safety needs can be developed. The educational strategy must consist of three components. The first is a means of presenting the needed information such as pamphlets, diagrams, a verbal presentation, a film or any combination of media called “stimuli.” The second component is audience response — an action that the instructors expects from the audience during the presentation whether it be oral, written or members of the audience performing an action. Feedback is the third component. The instructor evaluates audience response and reinforces the response if it is appropriate, or corrects it if not appropriate.

If a pamphlet or other written information is used as a stimulus, one factor to consider is the reading level of the target audience. It is especially important not to write above the audience’s level of understanding, but also not to insult the intelligence of the audience with oversimplified words and sentences. There are a variety of tests of readability, one of which is presented in the course. School systems usually have reading specialists who can be of assistance developing appropriate written materials.

Evaluation of the program is necessary to justify its continuation and to identify parts of the program that could be improved. This is best done through testing in which students take an oral, performance or written test before and at the completion of the instruction. Giving the test before teaching the material and then afterward produces useful information for the fire educator. If school children frequently answer one of the questions correctly in the pre-test, then that material needs little emphasis in the course. If in the post-test students tend to do poorly on a question, more emphasis on that point would be indicated. With a pre and post-test, the fire educator can show measurable learning as a result of the fire education program; an “85 percent” improvement in test scores, for example.

Statistical Analysis

Two days of the course are spent acquainting students with statistically sound methods for analyzing data. Fire educators must collect fire data and be able to analyze it to determine what the problems of their community are. Once a fire education program is initiated, it should show an impact on the targeted fire problem through a measured change in the fire statistics. When dealing with large amounts of data, a fire education manager will have to apply statistical methods to reduce the data into meaningful indicators of attitudes, achievements and trends. The course introduces useful analytical techniques, tests for statistical significance and the use of correlation coefficients.

Data analysis is a turnoff for most people, but it is a very necessary part of a successful fire education program. If the fire educator cannot identify the local fire problem or has only an intuitive feeling for what problems exist in the community, then he or she will have difficulty implementing an attack on the problem, not to mention trouble mustering community support for fire prevention projects.

In a typical community, the ages of fire victims may be represented by table 2. The fire educator wants to identify the age group which can benefit most from fire education and what the fire education message should be. Simply eyeballing the ages shows that there are a lot of fatalities among children ages 5 and younger, and that there are quite a few fire fatalities among persons age 58 and older. Unlike the student test scores, finding the mean, 38 years in this case, has no validity since there were only two victims that were close to that age. Likewise the median, 27.5 years, has no meaning either. In this case, it is best to group the ages together into common categories, such as preschoolers, adolescents, adults and older adults.

This grouping verifies the high-risk ages as older adults and preschool children. Fatalities occurred in other age groups, but there is no apparent trend there. (Inclusion of past years statistics might help identify other trends.)

Now the fire educator can see the more common causes of fatal fires in the two high-risk groups. In the senior citizens group, the fire causes look like this: kitchen grease fires, 1; solid fuel heating, 3; cigarette and furniture, 4.

Armed with information that the most common fire problem in the community is cigarettes dropped on furniture in elderly households, the fire educator can develop a program to educate senior citizens about the problem. Similarly, it is apparent that the second leading fire problem is children, especially preschoolers, experimenting with matches and cigarette lighters.

In this example, simply using a logical grouping of statistics helps the fire educator take aim on a specific problem.

A good method for analyzing data and presenting it is through the use of graphs. Graphs paint a visual image of a statistical relationship. Figure 1 is a histogram depicting the pre and post-test scores of the fourth-graders. It is not necessary to examine the numbers to see that the post-test scores are dramatically improved. In making a presentation on cigarette-related fires in a particular community, a good start would be with the bar graph in figure 2. An adult audience could immediately see that smoking-related fires are by far the leading killer in their community.

TABLE 1

Student Test Scores

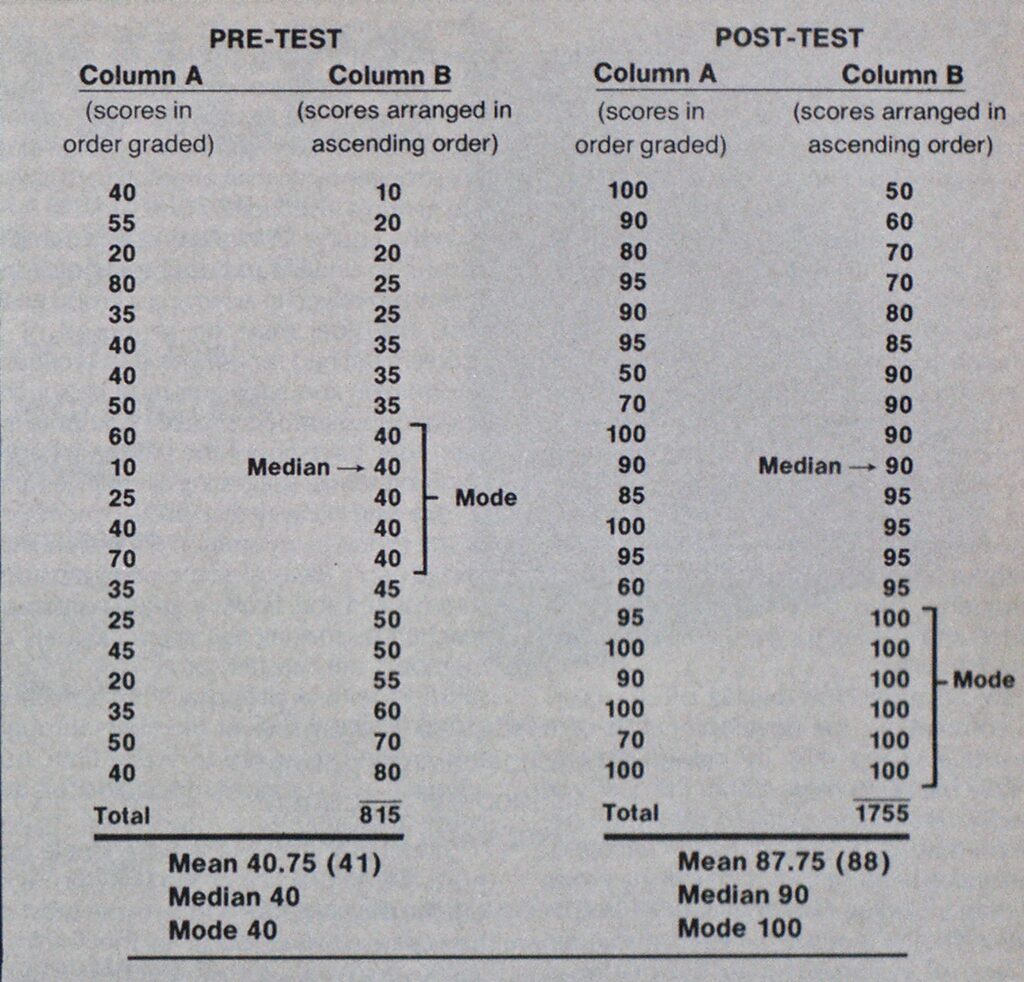

A common application of statistics in fire education is pre and post-testing. Table I gives a set of realistic scores from 20 fourth-graders before participating in a fire safety program, and afterwards.

Arranging the scores in order (column B) will help to “eyeball” the statistics. In column B it is easy to see that the most common pre-test score was 40. Five children made this score. The most common post-test score was 100, which six students achieved. This indicates that the program was informative. The most commonly occurring score is called the mode.

Another quick method of analyzing the scores is to find the median or midpoint. This is done simply by counting down the column to the halfway point, the 10th number in column B. In this example the median pre-test score, 40, is the same as the mode. Ninety is the median post-test score. Finding the median supports the conclusion that the students learned from the program.

The mean, which is commonly referred to as the average, is the most accurate way to analyze this particular set of data. The 20 pre and post-test scores are added and the sum divided by 20 to find the mean. Here 40.75, rounded to 41, and 87.75, rounded 88, indicate that the three measures, mean, median and mode, are close in both the pre-test and post-test scores. The mean reveals that the fire safety understanding of the class was increased from 41 percent of the tested concepts before participating in the program to 88 percent after participating in the program.

Human Resources

Good communication is a vital part of management and of public education. Communication involves not only sending messages but also receiving them. Students in the course spend an afternoon learning to be active listeners” through verbal and nonverbal feedback.

Many people are so intent on informing others of their experiences and their ideas that, instead of exchanging information, they blast each other with words. The moment one pauses to breathe, the other jumps in with a comment. When the conversation ends, neither person has any more understanding of the other’s perspective than before they started talking. Because a person listening can think faster than words can be spoken, it is easy for the listener’s mind to wander. The person speaking should try to be interesting and should exercise good speaking skills, but the listener must receive the message for communication to occur.

Good listening skills include asking questions for clarification of details, asking the meaning of a word the speaker has used, and negotiating with the person speaking where there are areas of disagreement. Paraphrasing what has been said is also an excellent way to listen and to provide feedback to the person speaking.

Nonverbal communication also contributes to active listening. Eye contact with the speaker is especially important. Nodding (not nodding to sleep!) and the emphatic grunt (“yes,” “yeah” or “um”) are also ways to indicate that one is listening, but the habit of nodding or adding “yeah” to the conversation automatically, without hearing what is being said, must be avoided. Also decreasing personal distance and leaning forward are signs of active listening.

Because decision-making often occurs in committees, the development of constructive group skills by individual committee members helps ensure the quality of decisions and also helps to speed the decision-making process along. A variety of disruptive behaviors can occur in the group setting including tardiness, lack of preparation for the meeting, a negative attitude, a lack of commitment to the matter at hand, dominating the committee or the matter at hand. These and other behaviors should be avoided, but individual group members must be able to counter the disruptive behavior by employing a variety of tactics. For example, a negative attitude can be somewhat overcome by turning negative statements into positive perspectives. A member who is dominating a meeting can be subdued by one member of the group asking for the opinion of another group member, thereby turning attention away from the dominating member. Calling on another individual is a stronger tactic than attempting to direct the group’s attention to one’s seif.

FIGURE 1

Fourth-Grade Fire Safety Course Pre and Post-test Scores

This histogram shows at a glance that students’ knowledge of fire safety has doubled as a result of their fire education course.

In the course of working as a group it is helpful to understand the basic functions that are involved in achieving a group goal. First, the goal must be proposed or a problem defined for the group to work on. Information about the goal must be sought and group members should contribute insight they have about the matter at hand, clarifying terms, suggesting alternatives and progressing in a way that will lead members of the group to a common understanding. The group’s ideas at some point must be summarized and, finally, a group consensus reached by making test proposals until all members are satisfied or at least not dissatisfied with a proposal. An effective group leader will steer members through this process so as not to waste time, but allowing for sufficient discussion of the issues and options.

Students in the course have ample opportunity to practice group skills throughout the two-week period because most of the class activities occur in the form of group projects. Other theories of persona and group interaction are presented and applied in a laboratory type environment with students observing and evaluating group members.

Principles of Management

An overview of the functions of management are presented in the course: planning, organizing, staffing, directing and controlling. In directing an organization a manager must have a sense of where the organization is going and how it may go about getting there. This involves goal setting, ideally accompanied by specific objectives and identified means of accomplishing them. For example, one goal of a fire department would be to reduce the loss of life to fires in its jurisdiction. An objective that would complement this goal might be to reduce fire deaths occurring in the community by 50 percent in a 12month period. The means of achieving the goal, also known as a performance standard, could be to install smoke detectors in 1000 low-income homes over the 12-month period. The planning func tion presents a definite direction and the setting of objectives helps move an organization through the daily masses of distractions that can leave a staff floundering with no measurable achievements.

Once a direction is decided upon, individuals within an organization should be matched with tasks. It is important for the fire education manager to understand the formal organizational structure so that assigned tasks fall within the appropriate organizational units’ responsibilities. This is usually not difficult in the traditional structure of fire departments where a rigid relationship exists between tasks and individuals. But it is essential that the manager also be aware of and use the informal structure of the organization.

The informal structure is less obvious but can be quite powerful: A battalion chief may possess considerable formal authority in the fire department, but a captain under him, who may be active in the union, may have a greater following and therefore be an important actor in carrying out tasks that will achieve established objectives. Winning over this individual could be the greatest asset in the program. An effective manager must also recognize the personal relationships that exist within the department that are part of the informal structure.

The function of staffing occurs when personnel are first hired by the fire department and when they are assigned specific tasks for the accomplishment of program objectives. The fire education manager should recognize the capabilities of the individuals in terms of their education, training and experience.

Directing requires the interpersonal skills of a manager to motivate personnel and to communicate well with them. A manager is responsible for counseling employees, providing discipline, building morale, leading and delegating tasks. With the exception of discipline, a fire educator coordinating a project also has to employ the above tactics with peers.

Some pointers on designing tests that will help evaluate a program:

- Do not use true/false questions. (Even guessing has a 50-50 chance of being correct.)

- Large numbers of essay questions are difficult and time-consuming to evaluate. It is suggested that essays not be used in evaluating a course.

- When multiple-choice questions are used, all the alternatives should be plausible and concise.

- Matching questions should be clearly explained in an introductory statement. There should be more possible alternatives than questions, and there should be three to six items to be matched.

- With completion questions (fill in the blank) more latitude must be given in grading because there is not always only one word or one set of words that correctly completes a statement.

- Blanks in a completion question should not be prolific and should be placed toward the end of the statement, so that enough information is given the student to initially avoid a wild guess.

- To prevent giving clues not relative to the subject matter, mark blank spaces with solid lines of equal length and write the sentence so as to avoid “a” or “an” before a blank space.

Finally, the manager must measure accomplishments and make necessary adjustments in the tasks so as to achieve the prescribed objectives. This is part of the control function of management.

Budgeting

In order for fire education to get its share of the budget, the fire education manager must understand the budget process and how to interact with it. The budget defines an organization’s policies and priorities for the coming year. If it is a policy of the fire department to educate the public about fire, then fire education needs should be reflected in the budget in terms of personnel and capital outlay. Its importance may be defined indirectly by the amount of money allocated to fire education or directly by the priority assigned to it. Students are exposed to the concepts of zero-based budgeting in which different options in service levels are defined by their cost.

FIGURE 2

PERCENT CAUSES OF FATAL FIRES 1977-1982 41 TOTAL FATALITIES

This bar graph pictures the numerical relationship of frequency of fire causes. This community’s biggest problem is smoking-related fires.

Management by objectives, another budgeting process, links the achievement of objectives to the allocation of funds. Students learn the fundamentals of program budgeting where the costs of personnel and capital outlay are split among the programs in which the fire department plans to engage. More traditional and less explicit, line-item budgets are also examined. Students learn the phases of budgeting and the factors that influence the budget cycle and they prepare a program budget for a specific fire education project.

Financing Special Projects

Fire education needs often exceed budget resources. Funds to buy video equipment, print pamphlets or to purchase smoke detectors may have to be sought from another source.

Alternative funding for fire education projects can come from a variety of foundations, corporations and government agencies. Nationally, $47 billion was given to nonprofit organizations in 1980, including some fire departments that used the right approach.

To receive funding, a fire problem should be identified and statistically substantiated, and a strategy for attacking the problem must be developed. Next, a source of funding should be identified. Check the public library for directories that list granting organizations such as: The Foundation Director printed by the Foundation Center in New York; The Foundation Grants Index: A Cumulative Listing of Foundation Grants, also from the Foundation Center; Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance from the Government Printing Office; and Annual Register of Grant Support printed by Marquis Academic Media in Chicago.

TABLE 2

Ages of Fire Victims and Cause of Fire (1982)

Some foundations grant monies only to educational institutions or specifically for research. Others are more community oriented and would be more likely to provide funds for a smoke detector campaign or to hire temporary employees to work on a specific project. The directory listings indicate the type of programs that fall within different criteria of the foundations.

A fire department should consider legal and ethical questions regarding private or public contributions and the use of these funds before approaching an organization for financial assistance.

Once these questions are answered and a potential funding source has been identified, a carefully written grant proposal can be prepared. Different granting organizations require various grant proposal formats. It would be wise to find out from the potential grantor exactly what is required before writing a proposal. Other nonprofit organizations that have received grants could give advice on how to go about writing a funding proposal and assistance may be available from other city departments.

The Management of Public Education course provides valuable information to fire education managers, from fire chiefs to teachers. Not only does the course present a wealth of practical concepts, it opens new horizons to students and serves as a vehicle for information exchange among students. It is hoped that readers can put information presented in this article to use, but anyone who is involved in fire education should go to the NFA and take the course!