In 2015, Loudoun County, Virginia, began the implementation of warm zone operations with departmentwide training. The training focused on establishing unified command, conducting combined warm zone operations and communications, learning how to operate the Joint Assembly Area (JAA), and the value of using live role-players as victims and provided many lessons learned, including “Just-in-Time” curriculum adjustments.

From March to June 2018, Loudoun County Fire and Rescue (LCFR) and its law enforcement (LE) partners conducted another departmentwide Act of Violence training event. The 2018 iterations sought to refresh existing personnel in the combined skills of LE and Fire/EMS (emergency medical services) (FIRE) in an Act of Violence incident (AVI), provide initial training to new LE and FIRE members, and capture lessons learned about Loudoun County’s readiness to respond to an AVI. Forty-one separate training iterations were conducted over a four-month period. More than 1,000 LE and FIRE responders were trained in implementing warm zone operations. Each training culminated in an AVI simulation with the deployment of contact teams, rescue task force (RTF) teams, and extraction teams and the removal of moulaged actors. These multiple training iterations presented intermediate lessons learned for responding to an AVI. These lessons were organized into seven categories: training approach, command and control, law enforcement specific, fire and EMS specific, communication center specific, regional specific, and future training recommendations.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Hostile Act Responses: Effective Command of the Warm Zone

Active Shooter Response: Rescue in the Warm Zone

Active Threat/Active Shooter Revisited

The 2018 trainings consisted of three four-hour sessions each week for a total of 41 RTF training sessions. This training had several goals: first, to refresh existing personnel in the combined skills of LE and FIRE in an AVI; second, to provide initial training to new LE and FIRE members who may not have received the initial training; and third, to capture lessons learned about Loudoun County’s readiness to respond to an AVI.

The drill structure initially separated LE and FIRE personnel into two groups. LE reviewed didactic information about RTF operations and conducted contact team skills review. Meanwhile, FIRE personnel reviewed tourniquet application, RTF operations, and tactical emergency casualty care (TECC). When the two groups reconvened, they jointly conducted facilitated review in RTF movements and care, team communications, and extraction of the injured from a warm zone. After these skill sessions, all participants returned to a staging area. Then, two full-scale AVI simulations were presented to the participants.

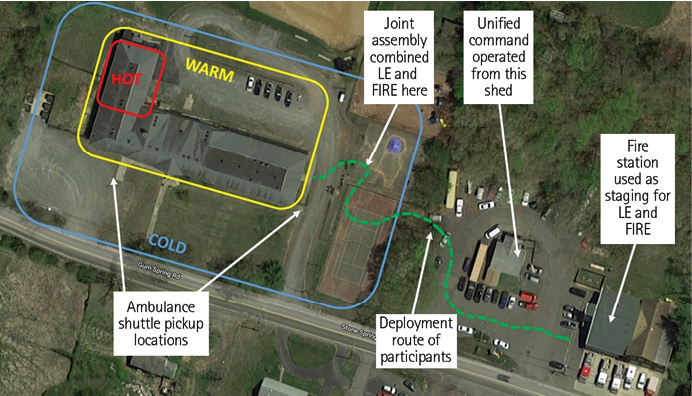

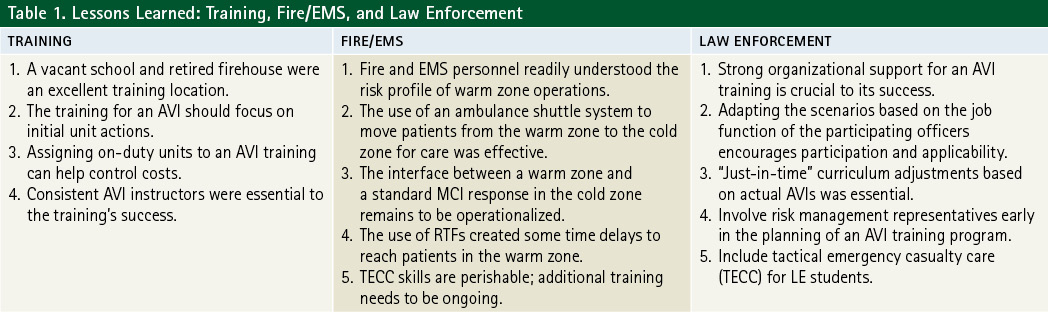

The full-scale simulations were conducted at a vacant one-story school that was scheduled for demolition. In addition to the LE and FIRE participants, there were five role-playing (moulaged) casualties and one active shooter role-player. The scenarios began with simulated calls to the 911 telecommunications center. The incident was managed with a FIRE telecommunicator and LE telecommunicator who had to coordinate situational awareness between each other and with units at the drill location. LE and FIRE units “responded” on foot from a retired fire station next door (Figure 1). The initial LE units deployed as contact teams while FIRE units prepared (a staging and a JAA) to form teams with later-arriving LE units to deploy into the warm zone. LE supervisors and FIRE chief officers also participated by establishing unified command. The formation of unified command was required before LE/FIRE RTFs were deployed into the warm zone. Morrissey (2018) pointed out that “active shooter incidents AVI exercises have far more value if the multi-discipline response has something for everyone, including leadership and unified command, contact teams, rescue task forces, and ambulance transport assets.”1 All of these components were included.

Figure 1: Preplan of Vacant School Used for AVI Training

Source: Loudoun County Fire and Rescue, Fire Station 609 Preplan Book, “Old Arcola Community Center,” 2014.

Lessons Learned

This was the largest (and longest) multiagency training drill ever conducted in Loudoun County. Over a four-month period, LE and FIRE participants numbered more than 476 and 624, respectively. Thirty-nine LE telecommunicators and 24 FIRE telecommunicators rotated through the training. A few dedicated FIRE and LE facilitators made these drills successful day after day.

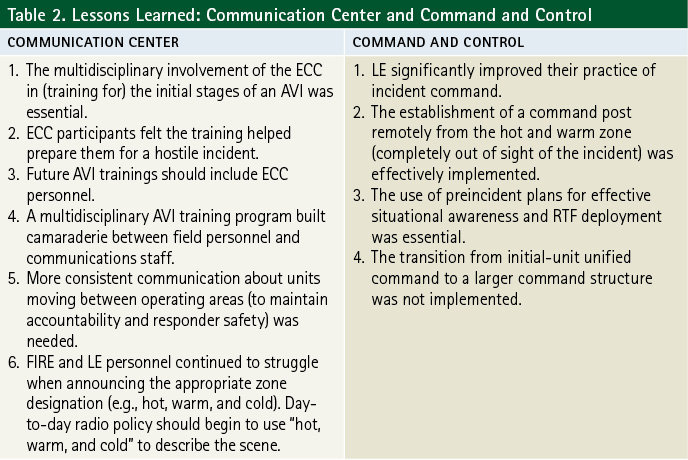

The 2018 AVI training yielded many lessons learned. After 2015, we learned many valuable initial lessons of implementing warm zone operations with LE and FIRE resources. In 2018, we refined these initial lessons and examined them further as we implemented them into our AVI response. These lessons were organized into seven categories: training approach, command and control, law enforcement specific, fire and EMS specific, communication specific, region specific, and future training recommendations.

Training Approach

Four training lessons were identified. First, a vacant school and a retired firehouse were excellent training locations (Figure 1). The vacant school was scheduled to be torn down so damaging the building was not a concern. LE was able to use simulated ammunition in the training building and FIRE was able to drag victims without concern for damaging the floors. The vacant school did require some careful safety considerations: Some weak areas in the wood flooring required patching with sheets of plywood.

Second, the training’s focus on initial unit actions proved effective.2 The training cadre felt that a focus on initial unit actions is essential for setting up for an effective LE-Fire (i.e., RTF) operation.2 If the initial operations and unit actions are not set up for success, the remaining wave of units will not be coordinated effectively. The drill focused on rapid deployment of contact teams, early establishment of unified command and a JAA, and rapid deployment of RTFs into the warm zone.

The third strength in the training approach was using on-duty units. Units were pulled from their emergency response stations or assignments and assigned to participate in the training. This allowed a large number of units to attend over a several-month period while keeping costs controlled. As Loudoun County is served by a combined career-volunteer system, training times were also altered to allow on-duty, volunteer-staffed units to attend in the evening and on weekends. This also allowed LE to train officers assigned to varying shifts and functions, including court, jail, patrol, and administrative positions.

Fourth, using consistent instructors was essential to the training’s success.3 This was a challenge considering the repeated iterations over a four-month period. Although instructors became fatigued, the cadre was large enough to allow sufficient personnel without negatively impacting the consistency of the training.2

Command and Control

Several valuable lessons were learned about Loudoun County’s ability to command and control an AVI. First, LE significantly improved its practice of incident command. It is important to highlight that the use of the National Incident Command System (NIMS) is a challenge for many law enforcement agencies.4 Unlike the fire service, many LE agencies do not use command in their normal day-to-day operations. The use of NIMS during this training highlighted LE’s strong ability to command an AVI. We believe this is a result of the previous 2015 AVI training in which LE supervisors learned the basics of operating a fixed command post. It should also be pointed out that “special weapons and tactics trained” LE officers were often much more comfortable operating as incident commanders than patrol officers.

A second lesson was the effective use of unified command between LE and FIRE to manage an AVI. The UFF Position Statement: Active Shooter and Mass Casualty Terrorist Events identifies the establishment of a single unified command between LE and FIRE as an important initial objective in response to an AVI.5 LE set up its command on the trunk of the supervising officer’s vehicle while FIRE positioned next to LE with its command module. An important recommendation from the Interagency Board is that disciplines at unified command are “within speaking and touching distance from each other.”2

LE used an AVI-specific command board to manage LE resources in the warm zone while FIRE managed their resources using their regionally approved Northern Virginia Consolidated Command Board. With these two boards placed next to each other (accompanied by their command officers), LE and FIRE were able to manage unified command effectively. AVI after-action reports emphasized the importance of LE and FIRE unified command: “The lack of unified command and inadequate communication between police, fire and EMS resources reduced (FIRE’s) situational awareness and exacerbated communication and coordination among first responders.”6 This identified the importance of unified command and communication.

A third lesson was the successful establishment of a command post remotely from the hot and warm zones—completely out of sight of the incident (Figure 2). This is a realistic issue in an AVI, and agencies should prepare for it. Furthermore, “The command post is not directly at the scene as to not be impacted by an expanding warm/hot zone.” 2

A fourth positive lesson was the use of preincident plans. In Loudoun County, the first-due engine company carries paper copies of its first-due public buildings (e.g., schools, churches, shopping malls). LE was unaware that FIRE maintained these “preplans” across the entire county. These “preplans” provided a map of the interior of the building for the LE commander to manage and guide teams in the warm zone. FIRE command officers were tasked with obtaining and orienting unified command to the use of “preplans.” The use of preincident plans is advocated in other AVI response policies.7

Figure 2: Overview of AVI Training Site Components

Source: Google Map, Arcola Community Center and Arcola Fire Station 609 (Gum Spring Road).

Two points of improvement were identified pertaining to command and control. First, a few tenets of NIMS were violated. For example, an RTF deployed into the warm zone changed its name in the middle of the warm zone operation. This created some confusion. Second, another lesson was the use of the term command for the initial LE and FIRE coordination to enter the warm zone (e.g., set up RTFs). Although we termed this command, we realized that this would become a branch under command. We termed it “Hostile Branch.” Although we determined this worked best to quickly coordinate LE and FIRE, the size and scope of an AVI would quickly develop other branches (e.g., EMS, Suppression, EOD). Ultimately, how to transition from this initial-unit unified command to a larger command structure would be a lesson for future training.2

Law Enforcement Specific

- The most important and valuable lesson was the existence of strong organizational support for this AVI training. This is an essential part of AVI planning.2 Attendance was mandated by LE leadership. This brought commitment to its success. Second, LE instructors were able to adapt the scenarios based on the job function of the participating officers (e.g., school resource officers, bailiffs). For example, several officers assigned to court duty participated. The scenario would begin with “a disturbance in Courtroom 3.” This allowed the scenario to be applicable to those particular officers and avoided a common active shooter training mistake—unrealistic scenarios.1 Third, LE made important “Just-in-Time” adjustments to its training objectives. A few days before the training began, the AVI training cadre learned of the Parkland shooting incident. Based on reports about this incident, the cadre adjusted (after review with LE leadership) some of the LE contact team tactics.

- Two other LE lessons learned were identified. First, based on the injury of an LE officer, risk management representatives should be consulted before future AVI trainings. Second, the cadre identified that LE must start providing TECC. This is consistent with the Hartford Consensus (2013), which stated, “External hemorrhage control is a core law enforcement skill.”8 Of course, this would not occur until after the threat is eliminated. Once the threat is eliminated, there is an inherent delay in the arrival of RTF teams, especially deep into the warm zone. By training LE who may serve on contact teams in TECC, patients can receive care earlier. Training officers in TECC was also a recommendation from the 1 October After-Action Report.9

Fire and EMS Specific

Several fire and EMS lessons learned were identified. First, fire and EMS system members did not demonstrate any hesitation on the value of entering a warm zone to provide care. In the first AVI training (in 2015), some personnel demonstrated a resistance to deploying with LE into the warm zone. This was not a factor in the 2018 training. This is consistent with the required paradigm shift required for warm zone operations by Smith and Delaney.10

Second, FIRE refined the use of an ambulance shuttle system to move patients from the warm zone to the cold zone for care. Initially, this approach developed from not having a large number of ambulances to role-play movement of the patients to hospitals. It was an effective strategy, especially with a scenario of approximately five critical patients. Five casualties is consistent with the median number of patients in an active shooter event.11

A third lesson was the interface between a warm zone and a standard multiple-casualty incident (MCI) response in the cold zone remains to be operationalized. Research has shown that an AVI MCI has different characteristics than a standard MCI.12 The delay in accessing the most severely injured and the “treat as you encounter” patients tactic of a RTF are two of the fundamental differences.12 During the multiple iterations of the AVI training, the ambulance shuttle was used extensively to receive patients at the edge of the warm zone into the cold zone. With patients moved out of the warm zone and off the scene, an effective transportation destination and patient-tracking solution (e.g., designated patient exit point) must be operationalized. They have been challenges in actual AVIs.6, 9, 13

Additional lessons learned directly affect patient care. First, one of us identified some disconcerting time delays for RTFs to reach patients in the warm zone. The vacant school was a small, one-story, one-hallway school with only 20 rooms. This was an uncomplicated building that lent itself to rapid deployment of teams. He timed scenario start until the patient reached a shuttle ambulance. In one case, the first RED patient reached an ambulance 23 minutes after the incident began. The last RED patient reached an ambulance 34 minutes into the incident. These were consistent times throughout the iterations of the training. A faster means of accessing and removing patients (or a faster means to bring more definitive care to the patients) must be considered.

The last Fire and EMS specific lesson learned pertained to TECC competency. TECC skills are perishable; additional training needs to be ongoing. As the training progressed, “quick reviews” on tourniquets and chest seals were required because many practicing EMS providers did not demonstrate strong confidence (or competence) with this equipment. Long-term and ongoing TECC training is needed for fire and EMS personnel.

Communication Center Specific

Several communication center-specific lessons were identified. First, Emergency Communication Center (ECC) personnel (both LE and FIRE) received a simulated 911 call and were required to manage the communications between each other and field personnel. The multidisciplinary involvement of the ECC in (training for) the initial stages of an AVI is an essential lesson.9 A survey of the ECC participants indicated that the training helped prepare them for a hostile incident. Future large-scale training should include ECC personnel.14 This training not only strengthens real-world operations, but it also builds camaraderie between field personnel and the communications staff.

ECC personnel also provided valuable feedback to the “scene” about the AVI training. ECC personnel pointed out that units often did not communicate when moving between areas (staging, JAA, for example). More consistent communication about moving across these areas will help maintain accountability and responder safety. During the scenarios, ECC was often unclear about what type of MCI resource was requested. Command personnel should be clearer in the specific MCI resource they request.

FIRE and LE personnel continued to struggle when announcing the appropriate zone designation (hot, warm, and cold) in the trainings.15 Locally, routine radio traffic on scenes requiring LE presence is “The scene is secure” (i.e., cold). This day-to-day vernacular continued to be difficult to change. Day-to-day radio policy should begin to use “hot, warm, and cold” to describe the scene.

Regional Specific

The region is well-prepared for an AVI, but it could always improve. In the training, officers and command personnel often struggled with the naming of the JAA.

The Northern Virginia Joint Action Guide directs a JAA to be established to form RTF teams. Officers assigned to this location would call it “Joint Assembly Group” or “JAG.” This was revisited on the regional level, which now encourages the use of “Joint Assembly.”

The interface between the warm zone into a standard MCI response remains to be operationalized. This was described earlier under Fire-Specific Considerations. In the continued revision of response manuals and operations, the regional partners should continue to stay focused on the endpoint (i.e., warm zone care quickly and safety). This could mean allowing for some small alterations for each jurisdiction’s operations while maintaining some conformity to allow effective mutual-aid response.

Future Training Recommendations

The 2018 AVI training cadre identified several future training recommendations.

LE and FIRE must continue working at the command level to identify the “right scenario” to begin RTF operations. Since the 2018 training, a few incidents have led to requests from FIRE to LE about attempting to begin setting up an RTF operation. Since few hostile incidents require it, continued clarification about “when” to implement this type of operation is needed.

RTF operations are the most difficult warm zone tactic to coordinate.16 Future trainings should consider attempting other LE-FIRE warm zone tactics such as protected coordinator or protected island.

Future RTF drills should be conducted in larger and more complex locations. This could mean multistory buildings, athletic complexes, or other complex buildings and facilities. Large open spaces would be other challenging locations.

Fourth, future trainings should consider conducting a complex coordinated attack type scenario. The “simple” RTF concept has been practiced at length. Perhaps, it is time to make the scenario much more complex. The 2015 and 2018 drills (appropriately) focused on the first unit’s actions to set up the “right” operation. Although Morrissey (2018) cautioned against overly complex scenarios, it is time for Loudoun County to move beyond the small scale (five-patient) scenario into the more complex operations.1

Successes

Several successes came from the 2018 AVI Training Drill in Loudoun County.

This was the second widespread implementation of warm zone operations with LE and FIRE. In 2015 and 2018, hundreds of responders in Loudoun County prepared to respond to an AVI. Conducting two large training events in merely three years is a strong benchmark.

These training sessions put FIRE and LE together. Now, individual firefighters, police officers, and command staff recognize each other on day-to-day incidents. The 1 October After-Action Report cited: “Personnel noted that a major strength of the response was their ability to easily integrate into a joint command structure because of their familiarity with each other.”9 Mutual respect has developed, and response has improved.

The county administrator attended and participated as a responder in the 2018 AVI training. The Interagency Board’s Active Shooter Hostile Event (ASHE) Guide (2016) cites the importance of senior leadership participation: “It is critical that senior leadership understands and supports the comprehensive ASHE plan. Without their active support, the planning process and any subsequent response will be jeopardized.Include senior leadership (including senior elected and appointed leaders and administrators) and private sector entities in training and exercises.”2 The attendance of the county administrator demonstrated the county government’s commitment to its first responders as well as AVI preparedness. He will understand the demands of such an incident if one were to occur.

One of our lead cadre was awarded the Award for Outstanding Contribution to EMS Emergency Preparedness and Response in Northern Virginia.17 The most significant success was the improved comfort and competence of our responders with warm zone tactics and patient care.

The last and probably the most important lesson of the 2018 AVI training is “not to become complacent in preparing for an AVI.” An AVI could occur at any time. Loudoun County’s AVI Work Group must continue to work to prepare with training, equipment, and planning. Training for an AVI must be integrated into LE and FIRE from the first day of their academy training.

References

1. Morrissey, Jim, “How to avoid the most common active shooter training mistakes,” EMS1. (https://www.ems1.com/rescue-task-force/articles/378089048-How-to-avoid-the-most-common-active-shooter-training-mistakes/). March 19, 2018.

2. Active Shooter and Hostile Event Guide (July 2016). The Interagency Board. (Retrieved from: https://www.interagencyboard.org/sites/default/files/publications/IAB%20Active%20Shooter%20&%20Hostile%20Event%20Guide.pdf).

3. Fire and Emergency Services Instructor, Eighth Edition. International Fire Services Training Association. Fire Protection Publications: Stillwater, OK, 2012.

4. Simpson, Gary, “NIMS: A Paradigm Shift for Law Enforcement,” Domestic Preparedness. July 19, 2006.

5. National Fire Protection Association (2018). UFF Position Statement: Active Shooter and Mass Casualty Terrorist Events. (Retrieved from: https://www.nfpa.org/-/media/Files/Membership/member-sections/Metro-Chiefs/UFFActiveShooterPositionStatement.ashx?la=en).

6. After Action Review of the Orlando Fire Department Response to the Attack at the Pulse Nightclub. The National Police Foundation. October 2018. (Retrieved from: http://www.cityoforlando.net/fire/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/11/OFD-After-Action-Review-Final5b98855d.pdf).

7. Hendershot, Robert, “Faster Care in Mass Shootings,” EMS World. March 2019. (https://www.emsworld.com/article/1222346/faster-care-mass-shootings).

8. Joint Committee to Create a National Policy to Enhance Survivability from Mass-Casualty Shooting Events. Improving Survival from Active Shooter Events: The Hartford Consensus. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons. ٢٠١٣; 98(6):14-16.

9. 1 October After-Action Report, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=814668). August 24, 2018.

10. Smith, E Reed and Delaney, John B, “A New Response Supporting paradigm change in EMS’ operational medical response to active shooter events,” Journal of Emergency Medical Services. December 2013.

11. Blair JP, Martaindale MH, Nichols T. (Jan. 7, 2014.) Active shooter events from 2000 to 2012. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. (Retrieved from: http://leb.fbi.gov/2014/january.)

12. Fire/EMS Department Operational Considerations and Guide for Active Shooter and Mass Casualty Incidents. United States Fire Administration. September 2013.

13. After Action Report for the Response to the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombings. The National Police Foundation. December 2014. (Retrieved from: https://www.policefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/after-action-report-for-the-response-to-the-2013-boston-marathon-bombings_0.pdf.)

14. Cotter, HR. “5 tips to form and train a rescue task force for active shooter incidents,” PoliceOne. Sep 21, 2016. (Retrieved from: https://www.policeone.com/police-products/tactical/tactical-medical/articles/223237006-5-tips-to-form-and-train-a-rescue-task-force-for-active-shooter-incidents.)

15. Wood, M. “Fixing the Rescue Task Force,” PoliceOne. Aug 20, 2018. (Retrieved from: https://www.policeone.com/special-operations/articles/479385006-Fixing-the-Rescue-Task-Force.)

16. Mueck, R. “Active Shooter Incidents: The Rescue Task Force Concept,” Domestic Preparedness Journal. September 20, 2017. (Retrieved from: https://www.domesticpreparedness.com/healthcare/active-shooter-incidents-the-rescue-task-force-concept.)

17. “2018 Regional EMS Award Winners.” Northern Virginia EMS Council. (Retrieved from: https://northern.vaems.org/index.php/awards/2018-regional-ems-award-winners.)

Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Loudoun County Fire and Rescue.

DANIEL J. NEAL, PhD, EFO, CEMSO, is a battalion chief with Loudoun County (VA) Fire and Rescue. Since 2015, he has supported active shooter training and served on the system’s high threat committee. He is also a certified tactical paramedic.

SAM NEGLIA is a retired supervisory special agent with national level experience in critical incident planning and management. He is a certified tactical paramedic, flight paramedic, and critical care paramedic. He has lectured on tactical emergency casualty care and active shooter response to law enforcement, fire/EMS, and emergency management personnel. He has been involved in developing, writing, and training all aspects of the Loudoun County (VA) Active Threat/Active Shooter response program since its inception. He remains an active paramedic with the Sterling (VA) Volunteer Rescue Squad. He has a juris doctor degree from New York Law School.

JOHN RICE, NRP, is a lieutenant with Loudoun County (VA) Fire and Rescue. He represents the fire and rescue system on the Northern Virginia Regional High Threat Committee. He has also led the department’s active shooter drills, manages the ballistic vest and Tactical Emergency Casualty Care program, and is the representative to the FEMA Complex Coordinated Terrorist Attacks Group. He was awarded the 2018 Northern Virginia Regional EMS Award for Emergency Preparedness and Response.