By Jaime Reyes

Recently, there has been a growing interest in fire departments that want to improve fireground communications. This makes sense given that most line-of-duty death (LODD) investigation reports cite communications as one of the factors that contributed to the fatality. We all want to improve our communications, but the problem is that we typically don’t know how to make that happen. It’s easy to say, “We need to be more concise in our communications,” or “We should talk on the radio only when the transmission is absolutely necessary.” But, how do we go about implementing these changes? Like almost anything else we aim to improve in the fire service, it all comes down to training.

![(1) Size-ups should be concise and from the cab when possible. The apparatus radio has more output power (wattage) than the portable radio, and there is less wind noise in the cab. Keep it simple. You’ll get more information after your 360, during your situation report. [Photo by Craig Hargrave, Plano (TX) Fire-Rescue.]](https://emberly.fireengineering.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/1905FE_Reyes-p01.jpg)

(1) Size-ups should be concise and from the cab when possible. The apparatus radio has more output power (wattage) than the portable radio, and there is less wind noise in the cab. Keep it simple. You’ll get more information after your 360, during your situation report. [Photo by Craig Hargrave, Plano (TX) Fire-Rescue.]

Set Goals/Review Past Incidents

If the overall goal is to improve our communications, we need to identify the issues affecting our communications and set some specific goals. Start by listening to audio recordings of structure fires to which your department responded. Take some notes and answer the following questions.

RELATED

Radio Messaging Under Warlike Conditions

Preventing Rapid Intervention Company (RIC) Radio Chaos: The 3/3 Option

Conditions That Warrant Urgent Communications to Command

• Are the majority of our radio communications easily understood the first time? If not, identify any communications barriers. For example, are there certain crews or individual firefighters who almost always sound clear and are easy to understand? If so, contact them and find out how they carry their radio and how they physically talk into the radio (especially while using self-contained breathing apparatus). Conversely, if some crews or individuals are consistently difficult or even impossible to understand, although it may be uncomfortable, let them know there’s an issue and work with them to resolve it. Doing this in a positive, nonpunitive, and helpful manner will help ensure that the message is well received.

• Are the majority of our radio communications necessary? If not, identify communication trends and include that information in your department’s communications training. For example, when giving a size-up, some officers forget to “keep it simple.” Instead of calling the structure what it is (a one-story house), they will call it a “one-story, single-family residential structure.” What’s interesting about this is that I know why they are doing it. It’s tradition. As firefighters “growing up” in the fire service, we listened to those firefighters in the front seat talking on the radio. They may not realize it, but the new members are watching and listening! Just like everything else the officers do, they are setting the example. It’s important for fire officers and chief officers to realize this and to make some positive changes.

(2) Fireground noise (e.g., pump panel) can hamper communications. Practice and be prepared. (Photos 2-3 by author.)

(3) A departmentwide approach, coupled with support from the top and buy-in at every level, is critical to improving communications.

The 3 C’s Communications Format

Anytime you make changes or try to modify behaviors, it’s important to provide clear expectations. Clearly defined expectations help to relieve anxiety and most likely increase “buy-in” and better outcomes. One way to do this is to adopt a communications model: “This is how [insert your FD here] talks on the radio.”

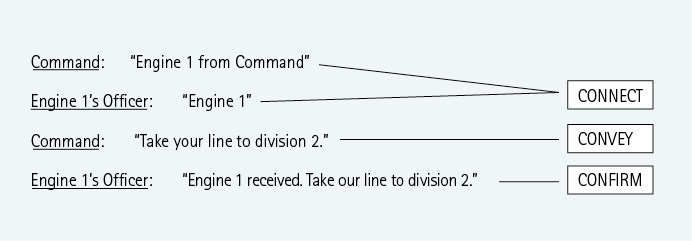

Example: Command Calling Engine 1

Our department adopted “The 3 C’s” format: Connect, Convey, Confirm. This format is a modified version of Mark Emery’s “4 C” model used in Fairfax County, Virginia, and other areas. The most important component in our 3 C’s model is Connect. If we get this right, the other C’s will fall into place.

The “Connect” happens when Engine 1’s officer replies, “Engine 1.”

Some members in our department were accustomed to replying, “Go ahead.” The issue here is that if the reply is, “Go ahead,” the connection hasn’t been made.

In this example, Command called Engine 1. What if Truck 1 thought Command was calling them and they replied, “Go Ahead”?

If that would have happened, it’s easy to see how a communication breakdown could occur. Command called Engine 1. When Engine 1 replied, “Engine 1,” Command knew for certain he was connected with Engine 1.

It is important to enforce that all communications follow this format. If we use the same communications model on every call (even medical or nonemergency calls), it will become second nature and we won’t have to think about it.

![Focusing on communications during training will pay big dividends when it matters most! [Photo by Mike Meyer, Plano (TX) Fire-Rescue Associates.]](https://emberly.fireengineering.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/1905FE_Reyes-p04.jpg)

(4) Focusing on communications during training will pay big dividends when it matters most! [Photo by Mike Meyer, Plano (TX) Fire-Rescue Associates.]

![(5) Putting it all together. Ladder throws with SCBA and radio! Practice like you play. [Photo by Doug Cross, Plano (TX) Fire-Rescue.]](https://emberly.fireengineering.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/1905FE_Reyes-p05.jpg)

(5) Putting it all together. Ladder throws with SCBA and radio! Practice like you play. [Photo by Doug Cross, Plano (TX) Fire-Rescue.]

(6) Coordinating fire attack with vertical ventilation requires communication. Practice the communication aspect regularly. (Photo by author.)

Add Communications to Training

Include a communications component in your training program. It’s no secret that fire crews across the United States are serious about their training. This is evidenced by an increased presence on many social media sites as well as an ever-increasing attendance at major conferences such as the Fire Department Instructors Conference (FDIC) International. Even in departments that have dedicated training divisions, most crews realize that they can’t sit back and rely on someone else to teach them new skills or help them to hone their craft. Crews are making the effort, getting outside and training. This is no doubt benefiting the citizens we are sworn to protect. It’s becoming more and more common for crews to go out and throw ladders, pull lines, and run through various scenarios including vent-enter-search or to discuss fireground operations in tabletop training sessions, but it isn’t commonplace to practice communications in the drills. With a little forethought, you can add a communications component to your training.

(7) Adding a communications component during Mayday drills is an absolute must. Start with the firefighter performing a fireground action (e.g., a search) and end with the firefighter successfully overcoming the emergency. During the drill, he should call the Mayday as soon as he thinks he might be in trouble. When possible, get dispatch involved in this training. (Photo by author.)

The next time you and your crew head out for some training, don’t forget to add a communications component. Before you exit your rig when pulling lines, why not give a size-up? Ideally, this would be done over the radio, perhaps on a training channel. It’s important that members talk on the radio during training because most of us are a little anxious when it comes to talking on the radio. Nothing relieves anxiety more than practicing. When adding communications to your drills, think about what would need to be communicated to other crews or command at an incident response. Having someone play the role of command for these drills makes it more realistic.

Include Dispatch in Training

Our department has provided training for dispatch annually since 2014. This “team” training has been beneficial in establishing lines of communication and getting dispatchers’ perspective on certain incidents and call types. It’s a great opportunity to share information; we look forward to it every year. These relationships are important for many reasons; the most important reason I can think of would be training for a Mayday. If the unthinkable happens, dispatch will be right alongside us doing its part to help us rescue our brothers and sisters.

During our annual training with dispatch, we include a variety of topics. We treat this training similar to the International Association of Fire Fighters’ “Fire Operations 101.” There’s an extensive overview of general fire department operations and terminology, followed up with very specific, detailed information. We explain why we do what we do so they’ll better understand just how important their job is to the success of our mission.

For example, we’ve recently asked our dispatchers to provide wind speed and direction to fire crews while they’re en route to a structure fire. At our last dispatch team training event, we demonstrated how wind can affect our fire scenes and the way we attack the fire. We showed excerpts from some of the UL Firefighter Safety Research Institute videos. The videos helped them understand modern fire behavior as it relates to flow path and wind-driven fires. They were very interested and asked lots of questions. The most important takeaway is that our dispatchers now understand certain terminology (e.g., flow path) and what we are doing and why we are doing it. When dispatch understands why we need the information, the dispatchers are less likely to forget or overlook it.

Measure Progress

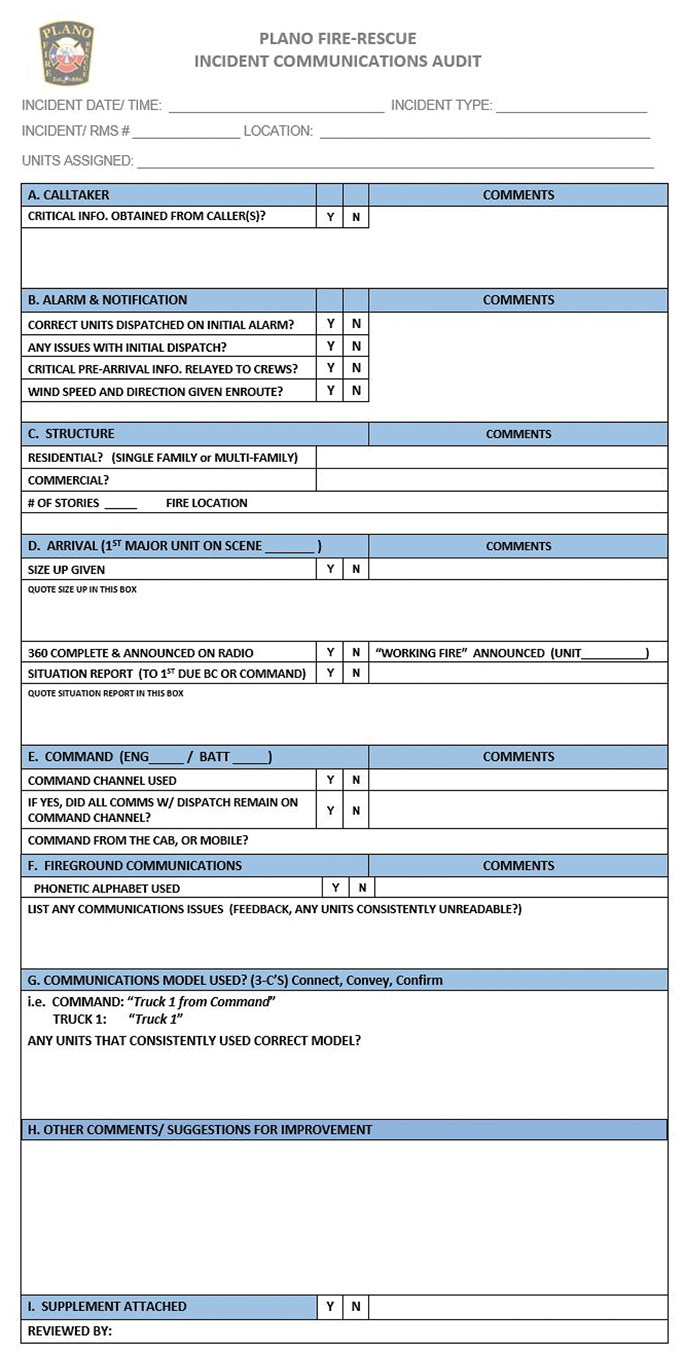

When reviewing radio traffic from previous incidents, it is helpful to follow a set format. One way to do this is to conduct a communications audit using a communications audit form. Our department is developing a communications audit, which is now in draft format. The goal is to improve communications; it is objective and nonpunitive.

Our communications audit starts with the fire department call taker: Did the call taker obtain critical information from the caller? What did the call taker advise the caller to do? It includes a section to evaluate dispatch: Were the correct units dispatched on the initial alarm? Did dispatchers provide adequate prearrival information to responding crews? The communications audit also identifies the first units on scene, the size-up and situation report along with the 360°, structure type, and how consistently the department’s communication model was used throughout the incident.

Stick with It

You have to be consistent when working to make improvements and implement change. Often, we’ve witnessed some excellent information delivered through a thorough training class only to later realize that there would be no follow-up: That was it; it was a flash in the pan. This is not only detrimental for the training topic or program, but it can also damage the credibility of the instructor and anyone who brought the training to the department. Before even entertaining the notion of improving communications, there needs to be a plan. That plan has to include follow-up, continuity, and—most of all—commitment.

Table 1. Draft of Communications Audit Form

Improving communications requires buy-in, consistency, and ongoing training. Before implementing a communications improvement plan, identify the current communications issues and decide the best way to address them. Start with the most critical issues (e.g., too much talking/radio traffic) and address the others along the way. All the while, keep in mind that the goal of improving communications will be accomplished through creating open, available airtime and ensuring clear and concise communications—communications that should be heard the first time, every time. Much can be accomplished by keeping it simple.

Jaime Reyes is a 20-year veteran of the fire service and a battalion chief with Plano (TX) Fire Rescue, where he is assigned to Operations/EMS. He chairs the department’s Fireground Communications Committee and is a certified master firefighter and instructor with the Texas Commission on Fire Protection. He is vice president of International Association of Fire Fighters Local 2149. He has a B.S. degree from Texas A&M University (1995).