Fire Departments Surveyed On Employment of Females

features

Although for years some women have been extinguishing fires as daytime volunteers while their husbands were at work, only recently have females begun to integrate into the fire service as paid fire fighters.

Some of the roles of women in the fire service are not new. For several years, women have been involved in educating school children, as well as the general public, in fire prevention and methods for coping with fire emergencies.1 Also, there have been women dispatchers since World War II. But what progress have they made into other fire service occupations?

In an attempt to learn the extent of female employment in the fire service, I contacted the United States Fire Administration (USFA) and discovered that there are no specific statistics on the status of female employment in the fire service. This prompted me to do a random survey to determine: (1) How many are employed in the fire service by occupation; (2) how women have performed in these jobs; (3) what are some of the barriers women face; and (4) what legal issues and laws are involved?

The information gathered dates from June to December, 1980, and reflects data obtained by questionnaire, personal contacts and interviews. It is not documented by any other source except where specified. The principal avenue for collecting data was a questionnaire which was designed to obtain a truly representative sample large enough to provide valid projection.

Affirmative action

The so-called affirmative action for the integration of women into the fire service is a subject that has been widely misunderstood and misinterpreted. It is also one that is being addressed by the USFA as one of the three top priorities announced by Gordon Vickery last year when he headed the administration. In an attempt to inform and educate fire service personnel as well as the public, the administration held three regional seminars on this subject in 1980 (East, Midwest, West Coast) and is currently developing experience data and other information on the subject.

Meanwhile, we have had the opportunity to witness a variety of results from attempts to resist or comply with “directives” on the hiring of women. Some have been comic, some tragic, and some satisfactory. The whole subject should be examined, and a good place to begin is with the law that started it.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 gave the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) the right to intervene in the employment practices for government employees. However, only the Department of Justice can initiate EEO action against municipalities. The thrust of this act and others preceding and following it, as well as presidential executive orders, was better utilization of non-white and female employees, but it was also stated that standards for employment did not have to be lowered.

Single standard acceptable

Affirmative action does not mean that a double standard should be used. The same performance criteria should apply to females as males. The purpose of all the laws, orders, rules and regulations2 is not to force the employment of females, but to protect them from discrimination based on sex. Thus, it is not legal any longer to say that women cannot be fire fighters because the duties are too rigorous for them, but it is quite legal to test their strength and agility and reject those who do not meet the same standards set for the male candidates.

1 “The Role of Women in the Fire Service,”FEMA, U.S. Fire Adminstration, August 1980.

To prove that there is no discrimination, it is important that the selection process be validated. The testing must be job-related and shall not discriminate on the basis of sex (or race, religion, color or national origin).

Title VII3 permits an employer to use a “professionally developed ability test,” including formal, scored, quantified, or standardized evaluation techniques. If there is an adverse effect on females, the test must be validated. There are three principal types of validation: construct validity, content validity and concurrent validation. Any or all of these may be used. Whatever method is used must be validated separately for women, and the job—as well as the test—should be analyzed to make sure the test will truly predict the required performance. The rejection of a female is considered justified if she cannot meet reliable and unbiased criteria based on careful job analysis.

Must be job-related

Arbitrary and unreasonable requirements for an applicant’s height and weight are not allowed. However, a performance standard requiring a person to be able to reach a certain height might be justified if the job-relatedness is proven to be valid.

Many fire departments are still using outdated physical requirements that are no longer valid, such as requiring that a candidate have two testicles (or one, for that matter). Since it has not been proven that testicles are essential to satisfactory job performance, it is no more reasonable to require them than it would be to require mammary glands. The essence of the matter is that a woman who has met proper qualifications cannot be rejected because of her sex alone, but that it is quite legitimate for one to be rejected for not meeting the requirements of a validated test.

When asked, during a recent survey, if entrance examinations and requirements were different for females than male applicants, 100 percent of the fire service organizations queried answered, “no.” This is an attempt, nationwide, to resist the lowering of entrance requirements for women or minorities. However, this does not mean that some departments need not examine their programs. Not only do departments need to assess their programs now, but they need to evaluate them frequently and make changes when necessary to maintain the level of qualified professionals in the fire service.

2 The basic control is the Civil flights Act of 1964 as amended by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972. Act ion. can also be taken under the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the National Labor Relations Act, the Age Discrimination Act, the Equal Pay Act, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Executive Order 11246 as amended by Executive Order 11375 and the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution.

3 Title VII of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972.

Many factors to consider

With or without affirmative action, there are still many factors that women must consider if they are seeking to become fire fighters. The job of a fire fighter requires that the individual be capable in fire fighting and rescue techniques and have the ability to make split-second decisions—sometimes life and death decisions—in an emergency. Fire fighting is generally accepted as a physical occupation and many women are more likely to select another occupation which they view as intellectually challenging instead of physically demanding. Fire fighting is also an unusually hazardous occupation and aside from a few adventurous females, not many women have shown interest in this kind of a profession.

The biggest obstacle, however, has been the social attitude toward women in the fire service. Men, and also other women, have made it difficult for females who are serious about making fire fighting a career. Some men are just not ready to accept women as equals in the fire service and some have been known to openly harrass and taunt female counterparts.

On the other hand, fire fighters’ wives, in some instances, have been openly opposed to female fire fighters because they feel personally threatened. The integration of women as fire fighters has become a fact of life, but not an easy one for many. Still, it appears that time and experience have eroded most of these fears, and the fire service as a whole is much more receptive to females now than it was a few years ago.

So, if it can be said that the initial shock has worn off and the trial period has been of ample duration, what is noticeable in the way of results?

According to a September 1980 report to Congress by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), there are approximately 250,000 paid fire service employees in the United States. My survey randomly selected 24 fire departments which employ 15,393 persons, or 6.2 percent of the total paid fire service. Of the 15,393 employees surveyed, 414 are females. Thus they represent 2.7 percent of the total paid fire service workforce.

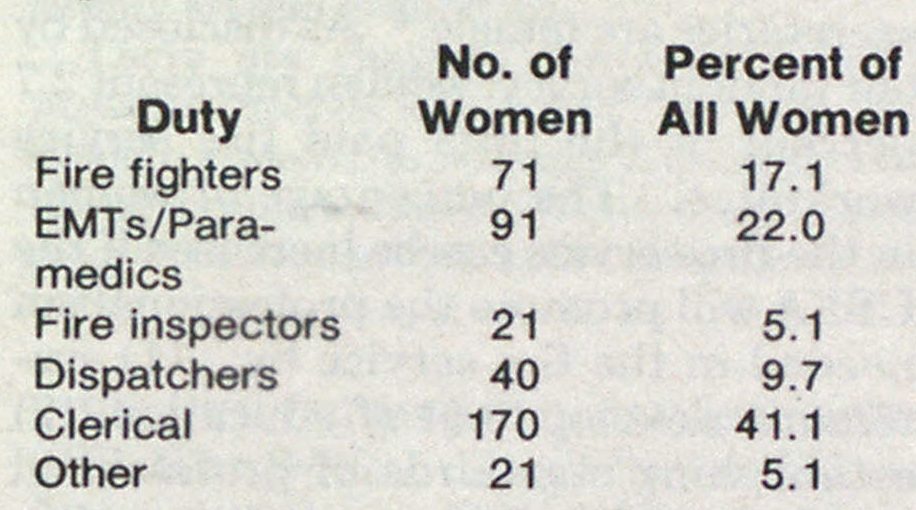

The following is a breakdown, by occupation, of the 414 women:

The total number of female officers revealed in the survey was two, or .5 percent of the total women employed in the fire service.

The numbers of women in the above duties differed from organization to organization, but it is evident that females are underrepresented in all of the duties. The range in percentage representation spanned from a low of .5 percent to a high of 21.4 percent of total organizational employment.

Entrance exam results

Almost all fire departments require written and/or physical entrance examinations; and all 24 departments surveyed responded that their entrance examinations are no different for females than they are for males. When asked how well or poorly women did on the entrance examinations, only 20 departments responded. The following information reflects how well or poorly women did on examinations:

These percentages reflect the opinions of female success or failure by t hose individuals responding to the survey. Sixteen of these same individuals responded to female fire fighters’ on-thejob performance as follows:

When asked how the female fire fighters’ performance compared to that of male fire fighters, those surveyed responded as follows:

Few fight fires

Of the 24 departments surveyed, 12.5 percent responded that they are required by court action to hire more females. To date it is unknown whether these court orders have had a positive or negative impact on the employment of women in the fire service.

The results of this random survey clearly indicate that:

1. Women are not well represented in the overall employment of the fire service.

2. Even fewer women are being selected for the more responsible positions.

3. It also appears that almost one half (41.1 percent) of the women still hold the traditional clerical positions in fire departments and only 17.1 percent are actually fighting fires (about one out of every 200 line fire fighters).

It should be noted that the larger departments surveyed had fewer females as a percentage of total fire service employees in contrast to the smaller organizations.

What can be done

In the United States today, females make up 51 percent of the population. Women currently hold 1 percent of the top jobs, whereas 97.6 percent of all our random survey, women represent 2.7 percent of the total paid fire service workforce. The percentage of women in the fire service can be increased if the USFA will promote the professionalism needed in the fire service by: (1) systematic development of education, (2) establishing standards of professional conduct which take precedence over personal gain, (3) disseminating information and knowledge to the fire service, and (4) establishing a nationwide minimum qualifications standard.

By establishing national standards, a basis of professional status can be built. Important too, is the establishment and acceptance of standards of education nationwide. Development of progressive attitudes and acceptance of innovations and changes that have merit will have a significant impact on the status of women in the fire service.

Those females who have been successful and are now accepted by their male counterparts are paving the road and making it somewhat easier for other women to qualify and enter the fire service. Nevertheless, social attitudes still remain as one of the largest deterrents to increasing female employment. This impediment cannot be legislated away and will probably remain for a while longer.

The results of my research seem to indicate women have a long way to go in achieving a representative percentage of total employment in the fire service.

References

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972.

Fire and Police Personnel Reporter, No.

55, July 1979.

Fire and Police Personnel Reporter, No.

56, August 1979.

Fire and Police Personnel Reporter, No. 67, July 1980.

The International Fire Chief, Vol. 46, No. 8, August 1980.

“The Role of Women in the Fire Service,” Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Fire Administration, August 1980.

“Vital Statistics,” Federally Employed Women News and Views, September/October 1980.

4“Vital Statistics,” Federally Employed Women News & Views, September/October 1980.