By Raul A. Angulo

The primary search and rescue of victims is the first and highest priority of firefighters at any fire incident. It can be the most challenging assignment to perform and presents the greatest personal risk to firefighters carrying out the task. However, an article on the subject of traditional search and rescue (SAR) cannot be simply regurgitated without a serious discussion on the philosophical changes of modern risk management parameters now imposed on fire departments. One is defining a rescue. The second is operating within the safety rating of our personal protective equipment (PPE). And third, are there certain situations where there is an acceptable loss of life? Every aspect of the American fire service is driven by risk management—even search and rescue.

Fire chiefs protect their firefighters by ensuring they have the best apparatus, equipment, and training available to carry out their mission. Elected officials ensure public safety by making sure the necessary resources are available to the fire department. In addition to protecting the public, fire chiefs and elected politicians also have to protect their cities from financial liability. They do this by adopting, or ensuring, that department policies closely follow the recommended National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards and best practices. The new NFPA 1700, Guide to Structural Firefighting is now published, and along with NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety, Health, and Wellness Program. These are the recommended best practices that fire department policies will be compared to, or, if adopted, will be held accountable to, in a court of law the next time they are sued by a family that has endured a line-of-duty death (LODD).

Even the wording of mission statements are driven by risk management. For example, these actual mission statements now use phrases like … to protect lives and property through fire suppression or, to provide professional and compassionate protection, education, and service to our community. Note that the words “rescue” or “saving lives”isn’t even mentioned in either example. It’s implied, but some lives cannot be saved. Many new mission statements use the word “protect lives” instead of “saving lives” because it is a broader and more achievable goal, with the least exposure to liability. A defensive “surround and drown” firefighting strategy on a building can be considered protecting lives and property that is threatened but not involved, while providing the least amount of risk to firefighters. Exterior ladder rescues and evacuating occupants down a stairway is saving lives while exposing firefighters to moderate to high risk. An interior search and the physical rescue of a victim in a burning structure, especially without the protection of a hoseline, is the greatest risk firefighters can take.

Risk-Managed Decision Making

To ensure the safety of all firefighters, a thorough 360° size-up including a risk/benefit analysis needs to be performed by the first-in company officer, typically the first-arriving engine. The ladder company officer (or the officer assigned to SAR) also has to perform a quick rescue size-up so an informed decision can be made to determine whether a SAR operation should be conducted immediately or delayed until interior conditions are changed in our favor through the use of water application and ventilation. The ladder officer should use the thermal imager to judge heat levels, identify the flow path, identify the fire location, and recognize heat signatures from any occupant close to the door for immediate rescue. Locating and confining the fire increases the operational window to conduct a search with less risk.

Rescue Size-up

A rescue size-up includes but is not limited to the following considerations:

- What is the location of the fire?

- Where is the fire headed?

- What is the speed of travel for the fire?

- What is the known or last known location of occupants?

- Where would probable victims be located?

- What is the survivability or rescue profiles?

- Where are the survivable spaces?

- What type of search patterns are best suited for this type of structure?

- Will this be a vent-enter-isolate-search (VEIS) operation?

- Is this a protect in place operation?

- Is forcible entry needed to gain access for the search?

- Are ground ladders needed to gain access for search?

- Are rescue ropes or other specialized equipment needed for the search?

- Can the search be supported with a coordinated fire attack?

- Will the fire attack be in progress?

- Can stairway and hallway egress routes be protected?

- Is ventilation occurring?

- How many search teams will be required to perform the primary search?

- Are there enough personnel and resources to effectively conduct SAR?

- Which technique do you intend to use to make the rescue?

- Can a porch or a roof serve as a work platform to launch the interior search, and be used for the removal of victims?

- What is the secondary means for emergency egress or forcible exit?

- Where will the emergency fallback location be for the SAR teams?

These are the questions the search team leader needs to consider in a rescue size-up, which can be performed in less than a minute. It’s not complicated; a rescue size-up basically comes down to: are there people to be saved, where are they, and can we get them?

Defining Rescue: What is a Save and What is an Assist?

There is a difference between protecting lives, saving lives, and rescuing lives. Words mean things, and in order to apply risk management principles to SAR while still performing them successfully at the highest level of effectiveness, we must be more definitive of the terms and parameters that go into this subject. Currently, the fire service hasn’t clearly defined rescue beyond the assignment. For example, an incident commander (IC) may simply say “Ladder 6, search and rescue.” Rescue must be defined for the purpose of risk management. Some instructors within the fire service are of the opinion that search is a separate assignment with distinct objectives that are different from rescue, and hence do not like to group the two terms together (search and rescue). There is merit in holding this position. For example, if a victim is found during a primary search and the search team switches to rescue mode, the primary search is interrupted and incomplete. There may be additional victims just beyond where the first victim was found. A delay in resuming the primary search may prove to be fatal for these remaining occupants. This is why ideally a search team should consist of four firefighters: two are designated for search and the other two are designated for rescue. Nevertheless, it can be assumed if a search results in finding a victim, they will be rescued.

“Protecting lives” is a broad, general phrase. “Saving lives” is more specific but can be accomplished without a rescue. For example, extinguishing the fire can save lives by eliminating the danger or threat. Guiding an ambulatory occupant to a stairwell, evacuating occupants down a stairway, or relocating occupants five floors below the fire floor are not technically rescues. Directing people to stay in their units and shelter in place or protect in place alsosaves lives, but they are not considered rescues. All of the above actions would be classified as assists.

What Constitutes a Rescue?

According to Webster’s dictionary, an actual rescue is “the act of saving, or being saved from danger.” Building and life safety code language includes, searching for, and removing victims or potential victims from a dangerous threat where they are incapable of self-preservation. It is also reviving them from the results of being exposed to that danger. A true rescue is saving an unconscious person, or a conscious person who is unable to extricate themselves from the fire and products of combustion without the assistance of a firefighter, either down a ladder or out an egress. Throwing a ladder up to an able person who is trapped by smoke and flames on a balcony is considered a rescue. Carrying an unconscious victim down a ground ladder or aerial ladder from a burning building is extremely difficult, stressful, and physically demanding. It is a heroic rescue in the purest sense.

A rescue is always saving a life. Rescuing someone who is already dead, though the firefighter’s actions may have been heroic and taken at great personal risk, is technically a body recovery. We may not like the way that sounds, but it’s actually determined by time. When the complete absence of any electrical cardiac activity occurs, the patient is asystolic (flatline), or dead. If a dead body were discovered in the rubble six hours after the fire was extinguished, would we call it a rescue? No, we would call it a recovery. What’s the asystolic difference between six hours and six minutes? Though the firefighter would probably be awarded a medal for heroism, it is a decision based on emotion and circumstance, not by the end result of what is considered a successful rescue. Per historical precedence, according to Fire Department of New York (FDNY) Battalion Chief Stephen Marsar, “the FDNY sets a 10-minute goal to conduct a primary search and to locate survivable victims. For the rescue to be considered a save, the victim must survive for 24 hours and/or be admitted to a hospital.”

A more agreeable way to look at it is to compare it to a water rescue, or a CPR resuscitation. If we rescue a person from the water and he lives, we say we saved him. If he died, we say he drowned. With CPR, if the patient has a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and survives, we would say we saved him. If he died, we would say the resuscitation was unsuccessful and we lost him. The time spent of resuscitation efforts isn’t a factor, only whether the patient lived or died. Therefore, “rescues” are based on survivability.

Rescue classifications can be broken down even further. Immediate rescues are “snatch and grab” rescues made just inside the doorway, the hallway, or around the perimeter of the structure. They also include interior rescues when the fire is in the incipient stage or growth stage within the compartment (the fire room). Once the fire flashes over within the compartment, the survivability profile is zero and beyond the safety rating of our PPE. However, numerous experiments conducted by the UL Fire Safety Research Institute involving SAR operations in residential structures have confirmed that if the fire compartment is isolated with a closed door, or if the exposure rooms next to the fire compartment are also isolated by closed doors, these barriers are effective in reducing flame spread and other products of combustion, thus improving the survivability profile within a burning structure. These are called survivable spaces. Therefore, our SAR and VEIS efforts should be concentrated there. In extreme cases, a person at a window ready to jump from an upper story requires the ladder company to quickly raise a ladder to the victim. This would also be considered an immediate rescue.

There is also self-evacuation and self-rescue, which can apply to a civilian or a firefighter. The names speak for themselves—they indicate a person or firefighter who was able to extricate or escape an immediate danger on their own without the assistance of others. And then there is rapid intervention rescue performed by the rapid intervention team or crew (RIT or RIC). Heavy rescue, water rescue, high-angle rescue, and confined space rescue, et al., are simply situational emergencies that require specialized equipment and techniques for firefighters to remove a person from danger.

Firefighter Safety Comes First

If you couldn’t swim, would you dive into a river or lake to rescue someone who was drowning simply because you were a firefighter? Some believe too much attention and emphasis has been paid in developing and implementing firefighter safety practices such as firefighter accountability systems, two-in/two-out, RIT and programs like the 16 Life Safety Initiatives, the IAFC Rules of Engagement, and Project Mayday. The argument is that these come at the expense of forgetting the first priority of saving civilian lives. There’s a sense that the training culture needs to shift back towards rescuing civilian victims, instead of placing a higher priority on firefighter survival and saving our own. Others from smaller departments with reduced staffing justify that perhaps their limited time and resources could be better used for an initial aggressive search, rather than taking the time and using valuable resources in setting up the two-in/two-out, RIT, or applying water on the fire. However, the commitment to set up these safety systems were the result of hard lessons learned by the supreme sacrifices made from previous generations of firefighters in order to make firefighting safer.

One must not forget that interior conditions can change rapidly with the creation of a new flow path. This sudden introduction of fresh air is often the result of firefighters making entry into the structure. Rapid fire growth can produce extreme temperatures above the safety rating of our turnout gear (approximately 500°F/260°C for 17 seconds of exposure.) When such conditions present themselves, departments with reduced staffing must try to knock down the fire and prevent it from growing before interior SAR operations commence. There are a variety of immediate tactics that can be applied to improve interior conditions, but applying fast water to the fire is the best tactic for cooling interior temperatures for trapped victims and firefighters alike.

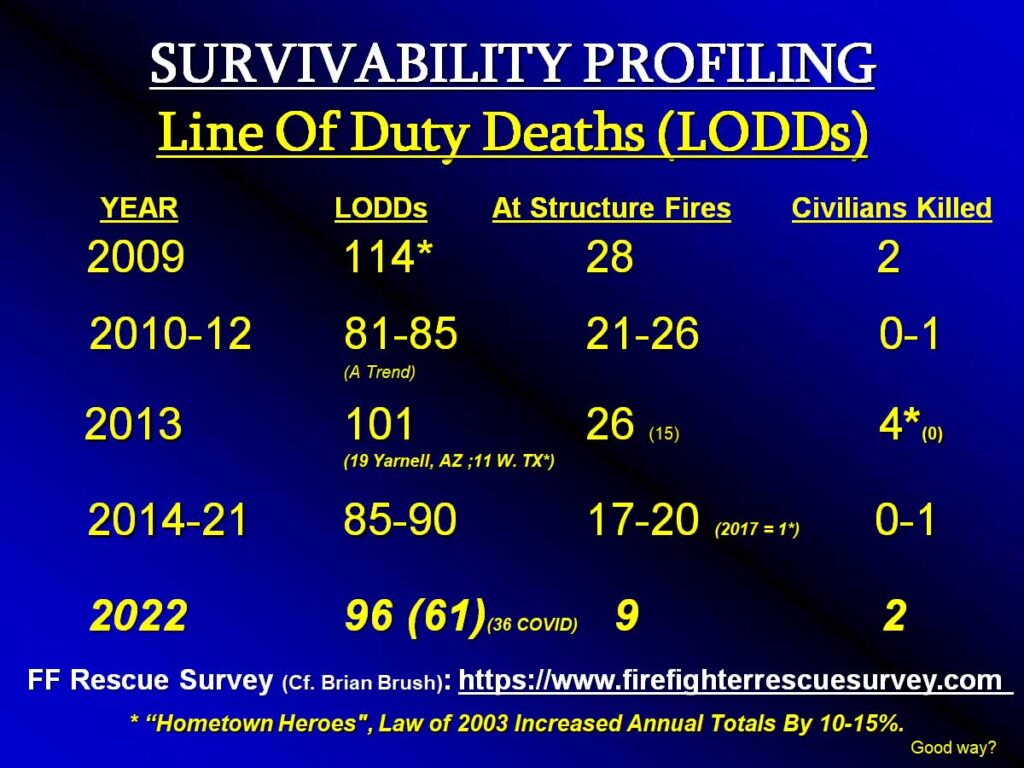

In the following historic incidents, the number of firefighter line-of-duty deaths (LODDs) is disproportionate to the number of actual victims who have been successfully rescued in those same incidents. In other words, they were not in the act of physically rescuing trapped occupants :

- 1988 Hackensack, NJ: 5 firefighters killed

- 1995 Pittsburgh, PA: 3 firefighters killed

- 1995 Seattle, WA: 4 firefighters killed

- 1999 Worcester, MA: 6 firefighters killed

- 2007 Charleston, SC: 9 firefighters killed

- 2019 Worcester, MA: 1 firefighter killed

- 2022 Baltimore, MD: 3 firefighters killed

- 2023 Baltimore, MD: 2 firefighters killed

There are certainly more examples. One fire department lost nine firefighters in a 20-year period…Charleston lost nine in one day! According to Chief Marsar, on April 24, 2022, a FDNY firefighter was killed in a house fire in Brooklyn , which also took the life of one civilian. This fire marks the first time since 1984 that a firefighter and a civilian were killed in New York City in the same fire. Sadly, there have been 39 other FDNY fire-related LODDs in between.

The reason fire departments exist is to extinguish fires. Historically, many departments were established, or converted from volunteer to fully-paid departments, after the result of a “great fire”–a conflagration that burned down a significant portion of a major city. It was in everyone’s best interest to extinguish the fire to protect their property. Great emphasis was placed on salvaging possessions from the fire. Preventing fires and protecting and saving lives were closely intertwined, but the first fire insurance companies were established to protect property.

Our mission has evolved to include saving lives, but many career paths also rescue and save lives: the Coast Guard, beach lifeguards, doctors, nurses, paramedics, police officers, etc. but only the fire department is responsible for extinguishing fires.

Rushing into a fire where interior temperatures are above the safety rating of your PPE for an immediate interior SAR without taking the seconds to put water on the fire to improve those conditions does not save civilian lives or increase the survivability profile, but it certainly increases the risk to trapped occupants and firefighters by allowing the fire to grow. Therefore, in those situations, we must change the interior condition to our favor (within the safety rating of our PPE) before operating inside of them.

To maintain situational awareness, many firefighters will remove a victim through the same Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health (IDLH) egress path they entered through. However, these conditions may now be worse for human survival. No amount of “aggressiveness” will change this fact. For trapped victims who are in survivable spaces, changing interior conditions to a favorable atmosphere is not going to lessen their chances for survival—it actually increases it. This is important to understand, especially for understaffed departments where both assignments, SAR and fire attack, cannot be carried out simultaneously.

It is also necessary to start considering alternate egress routes from these survivable spaces that will not drag a viable victim back through the IDLH the firefighter entered through. For example, using a reverse VEIS tactic—where a firefighter enters a survivable space from the interior, isolates that space, moves the victim to a window, and calls for a ladder—is a much smarter move.

Acceptable Life Loss

For the firefighter, risking one’s life does not mean to surrender or to exchange one’s life for another. Abandoned or deteriorated vacant buildings deemed “dangerous” due to holes in the floors, weakened or compromised stairways, and a lack of compartmentation (which will lead to unexpected fire spread) are a haven for squatters and transients. They are trespassing and illegally occupying that structure, and a fire in such a structure, accidentally or intentionally, was most likely started by them. In most cases, they’re not sticking around to be rescued by the fire department. Obviously, if there is visual confirmation that a person is trapped, the rescue should be made. This is somewhat analogous to surface rescues or perimeter rescues that would be made after a building collapse. In the latter, safety measures like shoring, for example, would be initiated to stabilize the collapsed area before firefighters would be allowed to start tunneling under debris into void spaces to check for survivors. Likewise, without visual or reliable confirmation of a trapped occupant, firefighters must resist the urge to initiate an interior primary search in the same fashion as a known occupied residence or business. Defensive control measures must be implemented first, and even then, the building may be too dangerous and unstable to enter. Risked-managed search must be applied. In this case, defensive search techniques should be implemented from the perimeter and outside the IDLH. Defensive search techniques include:

- Shouting or using a handheld megaphone to call out if anyone is in there.

- Checking and sweeping behind doors using a hand tool.

- Sweeping the floor area near the doorway using a hand tool.

- Scanning the floor and the room from a safe position or from the exterior doors and windows using a thermal imager.

- Putting up ground ladders or aerial devices to windows to call out, using a megaphone, or visually search for victims from the windowsill using a thermal imager.

Remember, glass is a highly reflective surface and acts as a mirror for infrared rays. A thermal imager cannot see through glass, making an unconscious victim on the floor invisible. The glass window needs to be taken out.

Look for signs of rollover. Remember, rollover precedes flashover and is your last warning sign before flashover occurs. If rollover is present , do not go through the window. Instead, crouch below the heat level and sweep the interior area below the windowsill with your longest hand tool. If a victim is visible or detected, the rescue should be made. Crawl below the heat level and pull the occupant to the safety of the ladder. Two or more firefighters (and probably additional ladders) will be needed for this rescue evolution.

When there is a danger of flashover at ground level, the firefighter should not go beyond the “point of no return,” that is, the maximum distance that a fully-equipped firefighter can crawl inside a superheated, smoke-filled room and still escape–alive–if flashover occurs. This is approximately six feet (or one body length) inside the doorway. If no victims are visible or detected, firefighters should not enter the building to search beyond what was visible or audible from the doorway, windowsill, or the ladder. If it turns out that a civilian fire death occurred in a dangerous building, this may have to be deemed an acceptable loss of life.

In his new book, My War Years, A Fire Chief’s Memoirs, (Dunnbooks), FDNY Deputy Chief (Ret.) Vincent Dunn has a chapter titled “Acceptable and Unacceptable Life Loss.” In there he states, “Acceptable life loss is an upsetting term…The polite term we use is triage, but it is really identifying acceptable life loss.” And he’s right. At a mass-casualty incident (MCI), firefighters and EMTs are taught to triage victims into four categories. Those who are uninjured or have minor injuries (green), those who are injured but without life-threatening injuries where treatment can be delayed (yellow), those who are seriously injured with life-threatening injuries but who can still be saved with immediate treatment (red), and those who have life-threatening injuries where survival is unlikely, or obviously dead (black). So, in fact, we already make those judgment calls on who lives and who dies. Why are we willing to make that judgment call at an MCI with some sense of confidence, but unwilling to make that call at a structure fire, especially at a fire involving a vacant, abandoned, or dangerous building? Dunn goes on to state that: “A vagrant’s death in a vacant building is an acceptable life loss. A firefighter’s death in a vacant building is an unacceptable life loss.”

For the City, It’s All About Financial Liability

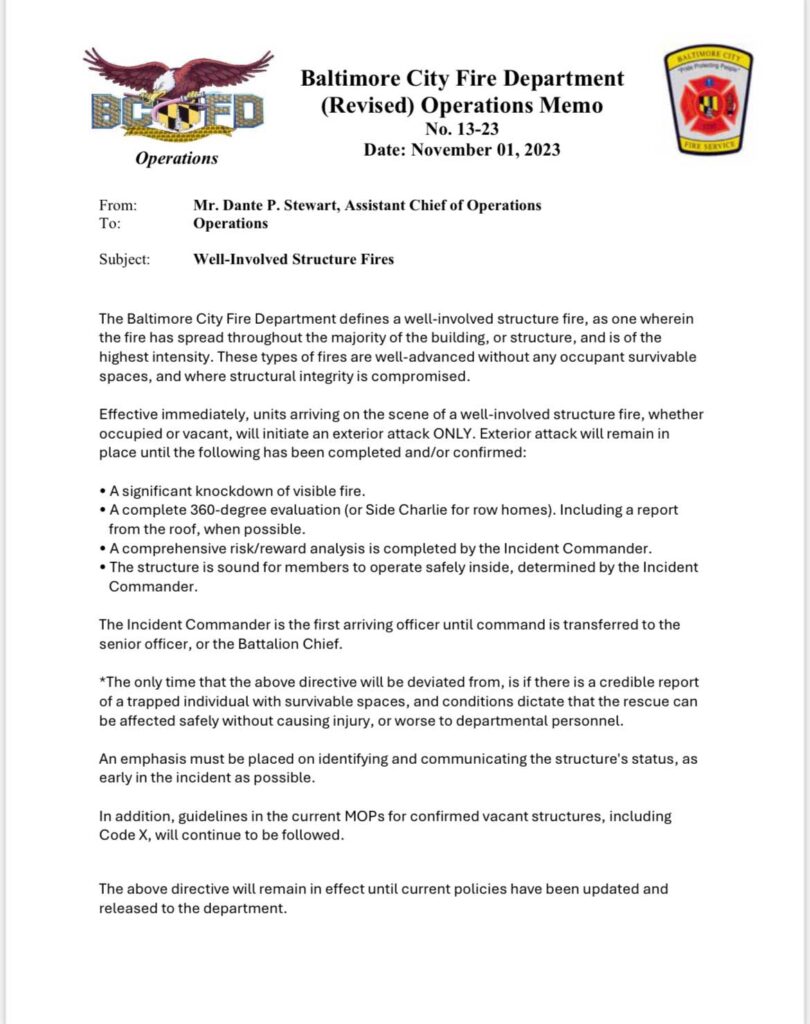

It is very unlikely a fire department will be sued because a civilian who died in a fire. On the other hand, it is most certain a lawsuit will be brought against the fire department and the municipality when a firefighter dies in a fire, especially when the only life hazard in the burning building is us. The fire service may not see what purpose is served by finding fault and blaming our own for a LODD, but I assure you, the city attorneys will have no trouble affixing the blame. This is why risk-management policies are applied to our most dangerous practices–to reduce that legal liability. It may sound like cowardice, but it is reality. The city coffers and insurance companies only care about one thing, and it isn’t heroics. The fire service needs to have the discipline and determination to apply all of our most recent scientific data into risk-managed size up. We cannot afford any more LODDs in vacant buildings. If incident commanders do not place firefighter lives above civilian lives, except in the event of confirmed trapped occupants, elected officials and financial bureaucrats who know nothing about fireground strategy and tactics will make that decision for us by installing policies that take away the initial ICs ability to make such decisions. In fact, the City of Baltimore (MD) is the first in the nation to do just that. After losing five firefighters in two years where there were no civilian lives at risk, the city faces financial and legal liability for all of them. In response, the fire department issued an immediate directive which basically states: Units arriving on scene of a well-involved structure fire, whether occupied or vacant, will initiate an exterior attack ONLY. The exterior attack will remain in place until the following has been completed and/or confirmed:

- A significant knock down of visible fire.

- A complete 360-degree size-up evaluation (or from Side C for row houses).

- A report from the roof when possible.

- A comprehensive risk/benefit analysis is completed by the IC.

- Structure is sound for firefighters to operate safely inside (to be determined by the IC).

The only time the above directive will be deviated from, is if there is a credible report of a trapped individual within survivable spaces and conditions dictate the rescue can be affected safely without causing injury, or, worse, to department personnel (implying death to a firefighter).

This quote from the late Phoenix (AZ) Fire Chief Alan Brunacini clearly reveals the cultural obstacle that prevents us from honestly addressing this problem. “When the fire kills us, our department typically conducts a huge ritualistic funeral ceremony, engraves our name on the honor wall and makes us an eternal hero. Every LODD gets the same terminal ritual regardless if the firefighter was taking an appropriate risk to protect a savable life or was recreationally freelancing in a clearly defensive place. A fire chief would commit instant occupational suicide by saying that the reason everyone is here today in their dress blues is because the dearly departed failed to follow the department safety plan. Genuine bravery and terminal stupidity both get the same eulogy. Our young firefighters are motivated and inspired to attack even harder, by the ceremonialization of our battleground deaths.”* As long as this remains the fire service culture, nothing will change.

Firefighters understand the dangers and risks of this job and what is at stake. But whether we like them or not, professional firefighters and officers must obey department safety policies; we can’t pick and choose which ones we will follow. Firefighters and officers who ignore or break safety policies are unsafe and unpredictable. Such a person doesn’t last long working for the fire department. Responsible firefighters will take increased risks after performing a thorough size-up and risk-benefit analysis to identify viable survivability profiles and spaces, and not surrender our greatest tools—education, judgment, and experience—to heroics. Firefighters are of high noble character. When the right “confirmed” situation presents itself to heroically save a life, they will risk everything, including their survivability, and aggressively do the right thing, but protecting firefighter lives comes first.

REFERENCE

Brunacini A.V., 2008. “Fast /Close/Wet: Reducing Firefighter Deaths and Injuries: Changes in Concept, Policy and Practice.” Public Entity Risk Institute, Fairfax, VA

Raul Angulo is Captain Emeritus (Ret.) of Ladder Co. 6, Seattle (WA) Fire Department. He has more than 40 years of experience and is on the editorial advisory board for Fire Apparatus and Emergency Equipment magazine. He is the author of the new textbook Engine Company Fireground Operations 4th Edition, (Jones and Bartlett Learning) and the soon to be published Ladder Company Operations on the Fireground, and has been teaching at FDIC International since 1996.