Training in the fire service, regardless of the size of the department, can be difficult to accomplish given the need to maintain effective response forces; manage overtime budgets; and, in the case of large departments, cycle hundreds of companies through the training. In any of these scenarios, training should still be a primary concern of the leadership. Recognizing the importance of training consistently is only the beginning of creating a high-performance organization. We must also design training programs that complement one another and are relevant to our organization’s weaknesses. It may be difficult to do all this, but this approach maximizes the precious time we have to prepare our response forces. The intent is to apply these principles to all of our programs so that each program complements the one before it through the chief officer certification.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Developing a Driver Training Program

Drill of the Week: Officer Training Schedule

This article focuses on the first three training phases or programs: Recruit Training (Academy), The Probationary Year, and Ongoing Training (centralized and decentralized)—programs administered by the organization’s Training Division. It is assumed that the in-house training conducted by company officers and crews is taking place. Although each training phase has a different feel and objective, the overall end state is the production of high-quality firefighters who understand their position on the team and can work through difficult problems in high-stress environments. Each phase of training should complement the one before it, building to this end state; making any phase of training its own silo creates inconsistent messaging that usually leads to confusion and frustration in the field.

Recruit Training (Fire Academy)

Recruit training can take many forms, from a total green academy (where the recruit has no prior experience) to a transitional academy (where recruits have experience from another department, typically shorter in duration). We will assume we are dealing with a completely green academy, as this is the most common type.

A solid recruit academy should be difficult. It should simulate as much as it can a high-stress environment where the competent performance of tasks is required. The desired end state of the recruit academy should not be mastery of these tasks, which is unrealistic.

For many years, this was my attitude and the attitude of many organizations for which I have worked. As I reflected on my experience training recruits, I realized that the 600 hours of instruction during academy were not nearly enough to master the skills taught. Instead, those initial hours of instruction were to gain an understanding of the fundamentals and to introduce recruits to thinking through problems as well as making decisions. They were to allow recruits to learn to function as team members. The recruit academy’s intention is to get firefighters to a place where they can function as a member of the team. That means they are competent; it does not mean they have mastered anything … yet.

As in my organization, I’m sure you have heard crews say things like, “What did they teach you in academy?” or something like that. This is because their expectation is, mistakenly, that a recruit is going to come out of academy as good as a three- to five-year firefighter, and that is just not the case. Any training officer will tell you that the amount of required information you must teach during an academy precludes you from the required sets and reps it takes to achieve mastery. So, if we cannot teach mastery in 600 hours but desire that as our end state, how do we get there?

15-Week Recruit Academy

In our organization, we run a 15-week recruit academy. If we decide to teach an emergency medical technician class within the academy, we add an additional eight to nine weeks on top of that. The state sets certain hour requirements for each topic, and we follow that fairly religiously, but we also want the firefighters to learn the specifics of our organization. A simple example would be a double donut roll. We teach this as a part of the curriculum, but we don’t spend a lot of time on it because we don’t use it in our organization.

Injury prevention is an important part of recruit training. Although we expect injuries to occur, we attempt to mitigate them as much as possible so that if we lose a recruit, it is because of performance, attitude, or academics, not injury. To address this, the academy was changed in 2010 from a 5/8 per week schedule to a 4/10 per week schedule. There were a few reasons for this; the first was injury prevention. We had been having the same recurring injuries happen in each academy and traced their origin to a potential lack of recovery time. We were able to decrease those injuries to zero with the addition of a three-day weekend.

The second reason for the change was time management. The eight-hour days caused us to lose precious time needed for repetitions after teaching through the classroom material. Once we changed to 10-hour days, we typically had those two extra hours to get in more skill work while the instruction was still fresh in the recruit’s memory. This led to better muscle memory and proficiency.

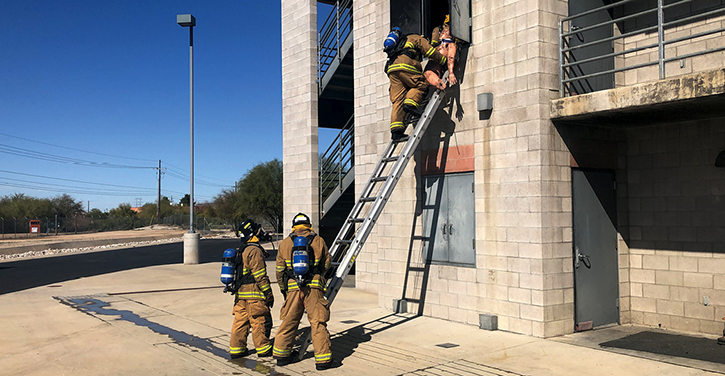

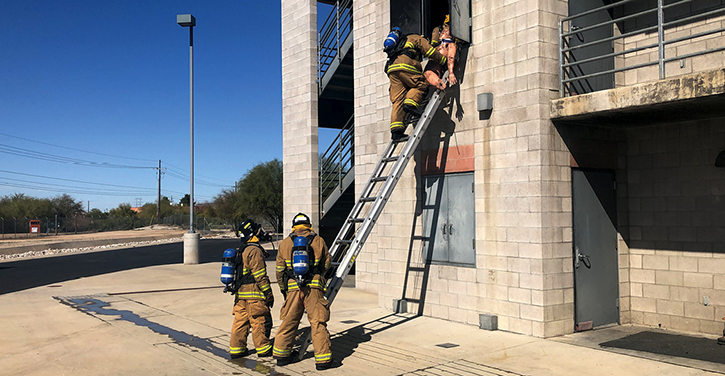

(1-2) Excellent organizational training is built on the fundamentals learned in a recruit academy. Those skills are then mastered during the probationary year. (Photos by author.)

Each day prioritized 11⁄2 hours for physical training (PT), high-intensity interval training that also involved many of the functional movements done on the job every day (deadlift, clean, hose drags, box jumps/step-ups, and so on). Cleanup is included in this time.

Directly after PT, the recruits are moved to the classroom for a quiz on the information on which they are about to be instructed. This may seem backward, but this process puts the onus on the recruits to come to class having already read the information so that it isn’t completely foreign to them. It eliminates the scenario where recruits rely on classroom information being fed to them and gives them some personal accountability. It also gives them an additional set/rep of the information, which yields a deeper understanding when they hear it a second time and then a third rep when they go out and perform the skill. Depending on the time of year, classroom instruction may be held in the morning or afternoon. When it’s 120°F, we will typically hold manipulative drills in the morning and classroom in the afternoon; we reverse that when it’s cold.

When dealing with the manipulative drills, no less than three-hour blocks (usually four) are scheduled so that all recruits can have adequate repetitions and can build strong muscle memory in each of those tasks. These manipulative skills stations are known as “core skills” and are always tied to the material being taught that week or in prior weeks. Stations are added throughout the academy until each four-hour block has four to five stations during a four-hour period. Specific skills are rotated each week to keep current on all skills. At the beginning of academy, recruits are assigned as teams (engine/truck companies); these teams rotate through each station, sometimes multiple times, until training is concluded.

The Probationary Year

Once recruits have proven that they can function in a high-stress environment, can still make decisions that drive toward the leader’s desired end state, and have shown apprentice level competency in the hundreds of tasks a firefighter must know, they graduate and are released into the field. This year in the firefighter’s career should be about mastering the fundamental skills learned in academy while applying them to real-world problems. Its end state should be to create thinking firefighters who can adapt to any situation given the vast toolbox from which they have to work.

Historically, our organization had a probationary program that was divided into modules. Within each of those three to four modules, only a few specific skills, like ground ladders and self-contained breathing apparatus, were prioritized; the remainder of the module contained administrative knowledge like standard operating guidelines (SOGs), policies, and procedures.

The effect this had in the field was companies training only on those tasks in the current module regardless of what area in which the firefighter might be weak. In short, probationary firefighters were being trained to pass tests, not to be proficient in all tasks. In practice, this might look like a probationary firefighter who was marginal at throwing ground ladders being in a module that wasn’t going over ground ladders; then, when the firefighter had to deploy a ladder at an actual incident, he did it slowly and poorly. At its core, this is a leadership problem, but the fact remains that it was the effect our program had on the company officers’ decision-making process. It never prioritized relevant training based on the individual’s needs.

Additionally, our organization had an issue where many cases of misinformation were floating around regarding the content in the probationary program. This issue was the result of giving probationary firefighters past completed modules for “reference.” When information in the modules changed, some probationary firefighters used the old information and ended up having the wrong answers.

An example of this was knowledge of hundred blocks for mapping. In our organization, you must memorize major hundred block intersections. Some of these hundred blocks would change over the years because of construction or because the previous firefighter got the hundred block incorrect and passed the wrong answer down to the new firefighter. We realized that to combat this situation, we needed a centralized, living document for all the current information the probationary firefighters were learning and it also needed to capture organizational “tribal knowledge.” It needed to be easily accessed by the entire organization at any time so that senior firefighters and officers would not only know what the recruits were learning in academy but could brush up on those same skills themselves by quickly referencing a section.

Manual of Firefighting (aka Probationary Firefighter Manual)

In February 2018, I rewrote our probationary program. Instead of a module-based system where we would incrementally and mindlessly put the focus on certain skills, we went with a singular document. The document is based on our profession’s best practices, our organizational SOGs, and some tribal knowledge from our senior members. That tribal knowledge is passed on in the form of “tactical considerations.” What’s more, the manual is a “one-stop shop” for all the information the probationary firefighter needs to be successful. This is how we combat misinformation problems!

The 200-plus-page manual begins with an explanation of the program, monthly check sheets for the officers and probationary firefighters to complete, and a four-page welcome/introduction to the probationary firefighter that lays out what to expect from station life. A previous academy instructor, who is now a captain and teaches a station life class toward the end of the academy, wrote the welcome letter. Its contents are heavily weighted in the tribal knowledge that we take for granted daily. The intent of this letter is to set each firefighter up for success; it gives them a starting place when they walk through the doors that first morning.

Blocks of Instruction. After the introductions, administrative tools, and welcome letter, the book is broken down into 17 blocks of instruction on all the fundamental tasks the firefighters should have covered during their academy time, and a few more. Some of the blocks contain multiple topics that may complement each other. If an SOG covered information on a specific task or block of instruction, that SOG was hyperlinked to the most current cloud-based version for reference. Whereas the academy curriculum had to focus on IFSTA and the state-recommended information, the probationary manual focuses on our organization’s specific loadouts, equipment, SOGs, policies, and tribal knowledge. Its intent is to take a deep dive into every facet of what we do and use to solve problems and take care of the community.

Each block of instruction is hyperlinked for ease of navigation; at the beginning of each block, a table of contents breaks down the material into basic and advanced areas for testing purposes. The basic information on a task is testable at the midterm test; the more advanced techniques or those techniques that may require more logistical support for the company to achieve are placed in the final test. As stated earlier, when progressing through each block of instruction, we capture the tribal knowledge from our veteran firefighters in the form of a tactical considerations section. These sections contain real-world scenarios and tips for the firefighters to begin to consider while still being based in the latest science. Furthermore, the manual enables us to capture many lessons that were previously lost when members retired.

The manual is saved in a digital format and housed on the platform we use for all of our decentralized training. The bulletin board of this online program has the manual on it and every firefighter in the organization can use it. The intent behind this is to provide insight to the companies about what is being taught on each of these tasks and to refresh their knowledge whenever they want to. To expand on that, I hoped that access to the information would further embolden the officers and firefighters to feel more comfortable in taking probationary firefighters out and drilling with them one on one.

The next step in the evolution of this manual, which is in progress now, is to video each skill and hyperlink the videos in the manual. This video-based task manual will show the “best practices” of each task. Each video will be housed on a cloud-based server and will be easily accessible by every firefighter in the organization.

Exams. As the probationary firefighters approach midterm and final exams, they will be scheduled for their written test at the training center. Both tests are 100-question exams covering the material broken down in each block of instruction. The students report to training; are seated in the computer lab; sign into their online account; and are assigned by the administrator the appropriate written test, which they have two hours to complete. The results are immediate, and the firefighters are sent back to their station with the results and, if they pass, a date for their practical testing.

During the practical test, the entire company reports to the training division. Although almost all the practical evaluations are for the single probationary firefighter, there are a few that necessitate that the crew charge and pump hoselines or assist in some other way.

Currently, there are 24 skill-evaluation sheets. Fourteen of these sheets cover the midterm instruction and 10 cover the final. The coordinator randomly selects four skill sheets from the midterm section that the firefighter must pass. At the final, three previously untested midterm skills and three additional skills from the final testable skills are selected. The intent is to ensure that firefighters are being trained across the broad spectrum of skills as opposed to focusing on passing known testable skills that are static from year to year.

Tracking Mechanism. The final part of the program deals with the tracking mechanism for the probationary firefighter. A six-section personnel file is broken down into multiple pieces. This file follows the probationary firefighter from supervisor to supervisor so that potential disciplinary trends as well as what each supervisor has prioritized in training each month are tracked and documented. The different sections are as follows:

- Personal information form.

- Company officer’s description/introduction to the program.

- Company officer check sheets.

- Monthly evaluation sheets.

- Six- and 12-month appraisals.

- Test results.

In our system, the recruit graduates the academy and is assigned to a station at graduation. The program designates where the probationary firefighter will be transferred at the six-month mark so that both captains are aware of whom they will be supervising for the entire year. The intent behind this is to develop dialogue between the officers from the beginning about how the firefighter is progressing. If a problem is noted in the first six months, the captain receiving the firefighter after the midterm is already in the loop and can continue working through the problem during the second phase of probation. In short, it develops a continuity in training, coaching, and mentoring, giving the firefighter the best chance for success.

Ongoing Training

One of the problems that our organization has run into has been the continuation of training fire companies. We have had difficulty covering out-of-service companies for training while still maintaining an effective response force without running up a massive overtime budget. Traditionally, we have attempted two formats—quarterly training and trimester training. Each has its advantages and disadvantages; both have fallen flat when the organization must also run an academy or other logistically intense program. To date, we have not been able to completely overcome this obstacle, but we do our best to provide as much centralized training as possible on a yearly basis. With that said, we recognized that our training, while excellent in many ways, was sometimes not done with an emphasis on relevancy.

Historically, our organization would select topics based on what we wanted to train on or what we hadn’t trained on for a long time. The problem with this was relevancy: A topic that we had not trained on in many years could be selected in spite of the fact that we were very proficient at it. This was a waste of precious time that could have been spent on topics we truly needed to refresh on—specifically, those high-risk, low-frequency tasks.

On the white board in front of my desk, I had the question, “Is it relevant?” up for many months. Every day, I looked at this question as I was thinking about how to best train our responders in centralized training (training conducted at the training division). The solution came in a two-faceted answer, which I explain below. It should be noted that the scheduling of the following two phases of training would take place every quarter in a perfect world but also might occur only once a year. The system is designed to function on whatever schedule you like as long as both phases occur one after the other.

Phase 1: Company Readiness Drills

To identify our training needs, we developed the Company Readiness Drills (CRDs) to function as a mechanism that evaluates the company’s efficiency and effectiveness in dealing with complex problems (running calls). They are truly nothing more than beefed-up minimum company standard (MCS) drills. These drills take approximately two to three hours to complete. We provide a prop-dependent scenario in which crews (two engines and a medic unit) have to deal with multiple moving pieces. In the first CRD we conducted, crews were given a two-story residential structure with a working attached garage fire and known victims inside the home. Crews had to address the fire, perform forcible entry (FE) through a simulator, conduct a search in zero visibility (smoke machines), and rescue a victim. Multiple stop watches were used to gather data points, which were analyzed after the CRD’s completion. These data points revealed some of the weak areas our organization had in training, which led to the determination of what the follow-up training package (TP) would cover.

Prior to and during the CRD, crews were not told how to solve the problem; they could run the scenario as if it were any other call and they were the first unit on scene. This produced 128 evolutions; the differences among them ranged from which lines were pulled to control the fire to which critical fireground factor they addressed in what order. In the end, these different solutions opened the training cadre’s eyes to options we had not considered, and the best of those options were discussed in the follow-up TP. The CRD clearly illustrated weaknesses, but it also illustrated the strengths of the organization. So, when the time came to develop the TP, each of the topics was a relevant need that most companies agreed they could work on.

At the end of the CRD, an analysis of data and a brief summation of the drill and its data were sent out in a documented After-Action Review (AAR) newsletter. Company officers could use this AAR, although not a traditional format, as a tool to further discuss the events and determine what was likely to be seen in the follow-up TP. For example, if the data showed time to entry (through the FE prop) to be slow, the officer could hypothesize that the TP would include an FE section and begin to prepare for that training.

(3) Company officers must set the standard for training daily in the stations. This decentralized training is evident when companies are scheduled for formal training at the training facility.

Phase 2: Training Package

When the evaluation phase of training was completed and the relevant topics were clear to the training cadre, we entered the second phase of the program, development of the TP. The CRD is a high-stress, edge-of-chaos type of scenario; the TP is its opposite. The TP is a low-stress learning environment where crews are refreshed on the best practices. They could ask questions while also being given the latitude to work on things that they had learned throughout their experiences or wanted to try if they had seen something new. The TP consists of the work-up and deployment phases.

Initially, within one or two months, the work-up portion of the TP was sent out through a cloud-based server. Each topic is covered in a traditional PowerPoint® classroom-based format that is usually accompanied by videos for clarification. Simulations designed to engage the entire crew in dialogue are embedded within the PowerPoint® program. An example of this format we just developed is a class on FE. Within the PowerPoint® are photos of the outsides of doors; crews could size up the doors together in their stations and identify what they thought was on the other side of the doors. They were then asked their plan for defeating the door. The following slide would have a photo of the inside of the door that would either confirm or deny their assumptions.

(4-5) Centralized training should be prop dependent and focused on high-risk, low-frequency events. Organizations should evaluate their companies’ strengths and weaknesses so their training programs are relevant.

Once the crews completed the work-up portion, they were scheduled for training. When they reported to training, they would hit the ground running. Each skill set that was prioritized as needing to be refreshed was set up in a lane or station; the companies were broken down into groups and rotated through.

These sessions were scheduled in four-hour blocks. The intent was to keep the crews moving, not waste time in the classroom, and to achieve as many sets and reps as possible in the allotted time, producing good muscle memory.

When it comes to training in the fire service, there are many ways to skin a cat. Most organizations, like mine, have a way they have always done it, and it has been perceived to work. This is only one way to accomplish training for an organization. Every organization should emphasize the continuity of training programs and their relevancy. Training time is a precious commodity; wasting that time on skills your organization is proficient in while ignoring weaknesses sets the team up for failure.

The training environment should encourage and motivate the troops while challenging them and setting the bar high to achieve the public’s expectations. An organization that doesn’t evaluate its teams’ proficiency in training is likely responding to incidents that don’t go right in the streets. This attitude is reactive and typically takes on the optics that you’re out to catch people getting it wrong. Take the proactive position: Evaluate your teams in the training environment, shore up weaknesses, and praise strengths. Catch your people getting it right and encourage them to that end. This approach will decrease organizational liability and boost morale.

IAN CASSIDY, a 20-year veteran of the fire service, is a training captain for the Northwest (AZ) Fire/Rescue District. He is a certified fire instructor II and fire officer III and teaches the NFA leadership series in Arizona. He has served in various leadership roles in divisions such as EMS, Training, and Special Operations (hazmat and technical rescue). He has assisted in reviewing new course content for Jones and Bartlett and was a contributing author to the ISFSI Training Officer’s Desk Reference.