By P.J. Norwood and Frank Ricci

“Can You Hear Me Now” is more than a line made popular in a series of commercials by Paul Marcarelli, brother of New Haven (CT) Fire Department Chief of Operations Matt Marcarelli. The line speaks volumes about a chronic issue our members face every day. Whether we are doing saw checkouts, responding in the canyons of tall buildings, or operating at a fire, hearing loss is an issue that can affect us all. Not all noise exposure can be reduced or engineered out, but the industry has made advances that can make a positive impact on your future hearing. There is not one of us who would like to be able to hear our grandchildren, the game on television, or the radio in our car; this is a quality-of-life issue, and the appropriate question we all should be asking is, “Can I hear you now and later!”

The hazards associated with our job are many and frequent; it is not possible to outline all that we face. Sure, we can assign safety categories and pick items to put in these categories, but truly analyzing and addressing these hazards is not always possible. Our jobs are very dynamic and ever changing. Each one of you reading this article will not fully understand every hazard you confront before the end of the today. Circumstances, experience, and teamwork will all have an impact on the outcomes.

LIMITATIONS OF ENGINEERING CONTROLS

Engineering controls cannot fix all our issues. Wearing hearing protection during saw checkout is just plan common sense. However, it does not translate well on the fireground for all applications. It is difficult enough to hear the radio and your partner with the saw operating.

(1) A firefighter venting a roof without hearing protection. The industry have not widely adopted controls for this application. (Photo by Peter Callan.)

When conducting roof operations in training, use ear buds when both members are trained in nonverbal communication. As a service, we must balance risks and our effectiveness. We have a dangerous job that must be recognized. The only way to eliminate all risk is to find a new vocation. That being said, we owe it to ourselves and our families to do a better job of evaluating and reducing risks.

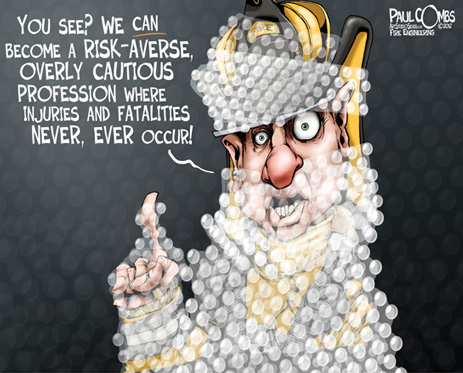

Fire Engineering Illustrator Paul Combs has many great safety illustrations. But to us, there is one that hits home, shown below: “Bubble Wrap Philosophy”

Leaders are in positions to lead and guide their memberships. They are tasked to be proactive, predict the needs of the organization, and put mechanisms in place to meet the specific needs of their teams. Those mechanisms need to solve problems, not be a shoot-from-the-hip answer that leaves people wondering. As professionals, we need to evaluate the work environment and put in place effective controls to help members anticipate and recognize problems before harm occurs to themselves or others.

Recently, the Safety Committee of the East Haven (CT) Fire Department (EHFD) identified an area of concern, took steps to evaluate the safety concern, and put together a proactive plan of remediation. Interestingly, the members who took on this responsibility all have more than 20 years on the job. They only saw minimal personal benefit from the mechanisms they have put in place today. For many, the damage or harm has already been done. Nevertheless, those in service are looking out for the department’s future generations.

One of the biggest challenges we have on the fireground is communication; it is listed in more line-of-duty death (LODD) reports than not. One of the fundamental issues here is the ability of members to hear each other so we can communicate effectively. Is it possible that your incident commander (IC) cannot clearly hear you because he has been exposed to high, unsafe noise levels of many different sounds (like the siren) for decades or has positioned himself in an area with high ambient noise? Both issues can be factors in missed communication.

When operating on the fireground in full personal protective equipment and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) we lose our ability to use all of our senses. When we encapsulate ourselves and put on a positive-pressure SCBA, one of the few senses that is not hindered is our hearing. However, many of us do not routinely take any steps to protect our hearing each and every day, and that can have a negative impact on our ability to truly hear on the fireground.

ENVIROMENTAL IMPACT ON HEARING

More than 1.1 million firefighters serve our communities, and many are volunteers. Although sirens on fire apparatus equipment are a primary source of noise, manufacturers have modified newer equipment to minimize this noise source. However, the firehouse and the fireground are still filled with items that will negatively impact your hearing. Other equipment such as chain saws, roof saws, and excessively loud headsets designed to overcome background noise can be contributing factors to hearing loss. We must not look only at our occupational exposure prior military experience; firearms training and hobbies such as music or perhaps even professional musicianship all play a role. Regardless, if it’s a symphony or a rock band, to the ear, noise is noise. Aging, genetics, medications, and infections can contribute or impact how well we hear today and in the future.

The outcomes or impact hearing loss can have on firefighters is not insignificant; it can cost more than we understand, and it’s not just dollars to which we are referring. Hearing loss isolates people—they get frustrated or distracted when they can hear, and others are equally frustrated by their lack of hearing clearly. Family members, children, spouses, relatives, grandchildren, and the public at large are included.

The ability to work as a firefighter can be restricted. Tinnitus (or ringing in the ears) can disrupt sleep, rest, reading, enjoying a movie with others, listening to music, sounds of a soft summer breeze, the quiet rattle of autumn leaves, a bird or chipmunk chirping, the buzz of a humming bird, or the soft whisper of a loved one. For those of us lucky enough to know these sounds, taking this ability for granted and not protecting others and ourselves from not being able to hear them does not mesh well with our mission as firefighters.

So, what can we do? How do we motivate others to take preventative action early and begin eliminating unnecessary harmful noise? Education is a key to success, for sure. We need to begin with educating our members on the realities and the human impact on hearing loss. Until we can truly help our members understand the impact, we cannot begin having a positive impact.

STANDARDS

Hearing standards for firefighters are addressed in National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1582, Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments. To safely perform under emergency conditions, the NFPA recommends that firefighters not have a hearing loss in their unaided (better) ear of greater than 40 decibels averaged at 500 Hertz (Hz), 1,000 Hz, 2,000 Hz, and 3,000 Hz during audiometric testing.

WORK ENVIROMENT TESTING

The East Haven (CT) Firefighters Union Local 1205 Safety Committee approached the chief of the EHFD, and together they formulated a plan to work together with the best interest of EHFD members. Through the guidance of the chief’s office, the committee reached out to the private sector. The city uses the insurance services of a private company; this company has many resources available to the EHFD to evaluate and create a safe working environment. The EHFD’s Risk Control Specialist (RCS), with whom they had already established a positive relationship, created a survey regarding noise levels during firefighting activities.

The purpose of the survey was to evaluate potential noise exposures during routine firefighter activities while operating apparatus sirens, horns, and pumps and while checking the function of powered cutting and extraction equipment kept on the apparatus. Sampling was not performed during firefighting. The survey collected personal noise dosimetry results and sound level measurements representative of actual exposure.

The RSC used his resources and spent two full days within the department evaluating the work environment. He evaluated the entire work environment, from the firehouse kitchen, lights and siren responses to normal road speed responses, radio communications, vehicle and equipment daily checks, and so on. Every area and task the firefighters performed during their shifts was evaluated. The environment was evaluated by having members wear personal dosimeters and using hand-held meters.

(3-5) Two types of dosimeters were used for work environment testing. A private sector risk control specialist measured sound during a daily saw check. (Photos by P.J. Norwood.)

SOUND LEVEL MEASURMENT RESULTS

We performed one-minute average sound level measurements while firefighters were operating various frontline apparatus and power equipment. Sound levels were collected inside the enclosed cabs of the fire trucks. For testing purposes, apparatus were run on a relatively inactive industrial road with sirens and horns operating and not operating, and with the windows opened and closed. Most firefighters indicated that they drive with the windows up and use the heat or air-conditioning inside the cabs, although this was not always the case.

The results during the frontline apparatus fire truck testing found that noise levels inside the cab exceeded the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA’s) Action Level of 85 A-weighted decibels (dBA) when the windows were down and the sirens/horns were activated. The results ranged from 88.4 dBA to 95.2 dBA. The sound level results with the windows up and sirens/horns activated ranged from 82.2 dBA to 85 dBA. These results indicated that the noise attenuation in the current vehicle cabs was sufficient to maintain noise levels at or below 85 dBA when the windows are kept closed. The frequency of calls/alarms and the duration of the drive time while signaling will vary.

RELATED: Maxon on Hearing Loss ‖ Strategies for Protecting Firefighter Hearing ‖ Hearing Impaired Firefighters

The highest sound level events recorded occurred during routine power equipment testing. The sound level results ranged from an ambient background level (no equipment) of 70.7 dBA to 111.5 dBA when operating the gasoline-powered ventilation saw. The various power saws and the pneumatic air chisel registered the highest sound levels, which were greater than 100 dBA.

HEARING LOSS PREVENTION GUIDELINES

Prevent noise-induced hearing loss by implementing an effective hearing conservation program that includes the following five guidelines:

- Use of hearing protectors, which can reduce noise levels at the eardrum to less than 85 dBA (and preferably to slightly less than 80 dBA). Make them available and encourage their use, particularly during the routine testing of apparatus and power equipment.

- Make training your highest priority not only to motivate employees to wear hearing protectors but also to wear them properly.

- Conduct annual audiometric testing of employees’ hearing acuity as required by the federal OSHA hearing conservation regulation when results are at or above the Action Level of 85 dBA. These periodic hearing tests on each noise-exposed worker are the only reliable method of monitoring the effectiveness of the hearing protectors being used and whether the individual employees are wearing them properly.

- Administrative control of exposure times to limit the amount of time any worker spends in high noise area can also reduce daily exposures.

- Engineering control of noise levels can and should be investigated and controls installed, if found to be feasible. The highest priority should be given to areas where average noise levels exceed 100 dBA, since hearing protectors may only marginally protect workers exposed to average noise levels of 100 dBA and above. Workers should wear both plugs and muffs where noise levels exceed 100 dBA if engineering controls are not feasible.

RISK IMPROVMENT RECOMMENDATIONS

The following recommendations represent measures that will improve the hearing conservation program:

- Establish an effective hearing conservation program, consisting of each guideline mentioned above, to protect your firefighters from the harmful effects of noise. Adhere to NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, Chapter 7.19, which requires fire departments to develop a hearing conservation program.

- As part of the hearing protection device training and education program, consider using commercially available fit-test systems that allow employees to “see” whether they are effectively inserting or wearing their hearing protection devices.

- Establish a Buy-Quiet Program and, when possible, replace equipment with low-noise equipment.

Having headsets in apparatus cabs can protect hearing and increase effective communications. With or without headsets, some manufactures recommend driving with the windows up. This is problematic, and most drivers and officers that I work with disregard this suggestion. Drivers like to be able to hear what is around them. The headsets offer the ability to still hear ambient noise while providing a level of protection to the ears.

It is critical for an officer to be able to communicate with the driver’s crew. Headsets provide for this need by offering a talk-around feature; it is mind-blowing that departments are still opting to purchase apparatus without them. These headset also allow the driver and officer to hear dispatch and alarm information cleared and without other outside distractions. As part of your equipment upgrades when designing or retrofitting frontline apparatus, consider using headsets for communications between the driver, officers, and firefighters, which can provide clear communications at lower volumes than conventional speakers that are turned up to overcome background noise. Some headsets can permit situational awareness sounds to be heard for life safety purposes and are often used in fire stations when backing up and maneuvering large apparatus.

All departments should have a goal to expose employees to average noise levels (for an eight-hour workday) of 80 to 85 dBA or greater while wearing hearing protectors and showing no hearing loss from year to year on their annual audiometric examinations. NFPA 1582, Chapter 6 (Medical Evaluations of Candidates), reviews Category A medical conditions, which can restrict employment as a firefighter. Hearing loss and related ear conditions are included in this section. Therefore, a well-implemented hearing conservation program can protect the hearing as well as the career of firefighters.

OSHA and NFPA recognize that using hearing protection devices may create an additional hazard for firefighters and emergency responders. Therefore, when it is deemed safe to do so, encourage them to use hearing protectors whenever noise levels exceed 80 to 85 dBA, even for short periods when average noise levels (noise dosimeter measurements) are less than 85 dBA for workers during an eight-hour workday. Although this is not required by federal regulations, consider it “good industrial hygiene practice,” a way to exceed OSHA and other related requirements, and to further reduce noise-induced hearing loss. Note that the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) recommends a threshold limit value (TLV) of 85 dBA, above which hearing protectors should be worn to prevent noise-induced hearing loss. Their TLV is modified downward to 84 dBA for nine-hour shifts, 83 dBA for 13-hour shifts, 82 dBA for 16-hour shifts, and 80 dBA for 24-hour shifts. The TLV also averages noise levels differently than the OSHA regulation, resulting in additional workers averaging above 85 dBA for an eight-hour workday and more workers being required to wear hearing protectors.

The fire service is in a unique position. During emergency scene operations, it is not possible to use hearing protection. For firefighters, responding to emergency events can prohibit the use of typical hearing protection devices (HPDs) because they can interfere with commands coming over the radio or while wearing SCBA, hearing alarm signals, building evacuation alarms, low-air alarms on SCBA or personal alert safety systems, and hearing calls for assistance from victims or other firefighters. The HPDs can also melt or catch fire, causing injury and creating additional hazards to the user. Therefore, restrict firefighters using HPDs to purposes as identified in the written hearing conservation program that do not include the fireground.

Because of the membership and a chief’s proactive vision, the members of the EHFDare safer today. Putting the members first is a win-win for all involved.

(6) Members of the East Haven (CT) Fire Department (EHFD) Safety Committee, the EHFD chief, and private sector professionals conducted the study. (Photo by P.J. Norwood.)

Hearing is critical for safety and quality-of-life issues. Work with your chief’s office, safety committee, and occupational experts to conduct a review of your workplace. At some point, your career and time volunteering will go away, but your hearing should not.

P.J. Norwood is a deputy chief training officer for the East Haven (CT) Fire Department and has served four years with the Connecticut Army National Guard. Noorwood has authored Dispatch, Handling the Mayday (Fire Engineering Books and Videos), co-authored Tactical Perspectives series on Ventilation and MayDay DVDs, and is a key contributor to the Tactical Perspectives DVD Series. Noorwood is a FDIC instructor, Fire Engineering contributor, Fire Engineering University faculty member, co-creator of Fire Engineering’s weekly video blog “The Job,” and hosts a Fire Engineering Blog Talk Radio show. He currently serves on the Underwriters Laboratories Technical Panel for the Study of Residential Attic Fire Mitigation Tactics and Exterior Fire Spread Hazards on Fire Fighter Safety. He has also lectured across the United States as well and overseas. He is certified to the Instructor II, Officer III, and Paramedic level.

Frank Ricci is a contributing editor and advisory board member for Fire Engineering. He is a battalion chief for the New Haven (CT) Fire Department and co-host for the radio show “Politics & Tactics.” He is also a contributing author to the Firefighters Handbook I & II (PennWell, 2008) for the “Safety and Survival” chapter written with Anthony Avillo and John Woron. He was the project manager for emergency training solutions for the Firefighters Handbook I & II slide presentations. He has been a FDIC hot instructor and lecturer. Ricci won a landmark case before the U.S. Supreme Court, testifiying before Congress, and has been a lead consultant for several Yale University studies. He has worked on a heavy rescue unit, covering Bethesda and Chevy Chase, Maryland, and was a “student live in” at station 31 in Rockville, Maryland. Ricci also appears in Fire Engineering’s digital blog “The Job.” Ricci developed the Fire Engineering film “Smoke Showing,” is a co-creator of Fire Engineering’s “Tactical Building Blocks” poster series, and is a part of several “Training Minutes” segments. Ricci has authored several DVDs including “Firefighter Survival Techniques” and Fire Engineering’s “Tactical Perspectives ” series “Command,” “Ventilation,” “Search Mayday,” “Fire Attack,” and Dispatch, Handling the Mayday.”