Volunteers Are Capable of Adding Prevention to Suppression Efforts

features

Fire Prevention in Action

The purpose of this article is to encourage volunteer fire departments to engage in comprehensive fire prevention programs.

Almost all volunteer departments still devote most of their efforts to activities classed as “fire suppression.” These activities are designed to extinguish fires after they start and include not only fire fighting itself, but also drills and training, apparatus and equipment maintenance, and similar tasks.

Obviously, our attention to suppression work cannot be relaxed, but the time is certainly here to consider the other side of the community fire safety problem. This other side is fire prevention, and it recognizes that reducing the occurrence of fires is much better for a community than putting them out once they begin.

Five types of activities

Modern fire prevention is composed of at least five types of activities, all sharing the same objectives of reducing the number of fires in a community and minimizing the harm to people and property from the fires:

- Making new construction safer through the adoption and enforcement of building construction codes, an approval process for building plans, and occupancy certification standards and procedures.

- Enforcing building, safety, and fire codes through inspection and legal procedures, licensing certain hazardous facilities, and adopting codes and ordinances as required.

- Reducing arson through investigation and prosecution, and through the collection and analysis of data regarding fire setting.

- Collecting information and statistics helpful in community master planning, such as standardized fire reporting data, case histories, and research findings.

- Increasing public action toward fire safety education and training, promotion of safeguards, building evacua-

- tion plans, plant protection, hazardous material and devices safety, and installation of early warning and other protective equipment.

Three hurdles

Volunteer departments can engage in each of these, although three hurdles are often present. First is the erroneous concept that only larger cities need comprehensive prevention programs. The second is based on the idea that volunteers will do only fire fighting work. The third stems from the fact that smaller communities often do not have codes relating to fire safety.

However, tremendous progress has occurred over the past five or six years, and advancements have taken place in two areas, each relatively new to the fire service and especially important to the current movement for greater national fire safety.

The first area of advancement is part of the newer approach to estimating the total cost of fire to a community. This approach adds together the cost of suppression equipment and activities, fire loss, and possibly even such related expenses as fire insurance premiums, lost business, etc., to get a more complete picture of the price of an unfriendly fire. When injuries, lost time, and deaths are somehow calculated into the formula, the total sum may be staggering. Looking at fire cost this way is a bit different from simply calculating the cost of “fire fighting,” which in smaller, volunteer departments especially, may be quite low and deceiving.

A small, rural department may be able to heat the station, buy gasoline, and maintain equipment for several thousand dollars a year. But this is hardly the total cost of fire to the community, since at least the annual fire losses need to be added in. Unfortunately, some recent research and statistics are beginning to demonstrate that the fire loss in many small communities is relatively large. One recent study indicated, for example, that the incidence of fire loss in towns with populations under 5000 is disproportionately high.1

Reduction is best route

Reducing the fire loss appears to be the best way of cutting down the total cost of fire, and eliminating some fires before they start appears to be the best and least expensive way of reducing the fire loss. Certainly injuries and deaths which do not occur are a great savings in themselves. This newer total cost of fire approach to planning is important to volunteers since fire prevention efforts typically cost less than additional suppression equipment, and time spent in prevention work may help more than other additional efforts. Research indicates that “small towns which invest proportionately more for fire prevention have a lower rate of fire incidence.”2

It might be estimated that 99 percent of volunteer task time is spent on suppression business—and 99 percent of budget money as well. Some reallocation of time, or some additional time spent in prevention activities appears to be desirable. A slight shift in organizational structure might be necessary, with perhaps a fire prevention officer elected or appointed, but this can be accomplished without great commotion, just as EMS duties have been added to what are basically fire fighting organizations.

More scientific approach

The second area of advancement in the prevention field is the result of a more scientific approach to public education. At least two major organizations, the United States Fire Administration and the National Fire Protection Association, are studying ways of changing public behavior toward fire safety education.

For many decades, almost every volunteer department which engaged in fire prevention work did so only during Fire Prevention Week, and programs were typically limited to schoolchildren. Often, these programs were really demonstrations of fire fighting equipment and not geared to the age, interests, and attention span of the students, nor designed to teach fire safety. What was demonstrated in some cases was that fire trucks are exciting and can be summoned anytime the red box is pulled. We know now that the concept of comprehensive fire prevention education encompasses much more than school demonstrations and that one week a year is hardly sufficient.

Several nationwide public education programs are operating now with measurable results and these programs reflect what has been learned from earlier experience and research. For example, with modern media such as television available, sustained programs of high quality can be projected nationally to millions and local programs can be keyed to the larger campaigns. School curricula designed by experts are already in fairly widespread use. Since the content, material and methods of teaching are already designed, local fire departments need only stimulate the local school to pick up the packages.

Reinforcement of the learning takes place as the children view television messages, hear radio announcements, and read the same words in newspapers and magazines. Within the last seven or eight years, for example, the number and quality of fire prevention films has increased a good deal. The newer campaigns are positive in approach and interesting to children, adolescents and adults. Large corporations seem willing to help support the work, and vast attention is now turned toward ways of protecting lives and property from fire through good fire prevention programs.

Fight against arson

A second fire prevention activity which volunteer departments need to be associated with is the strong national drive to reduce arson. Large insurance companies and others are putting experts and financial resources into the movement, and more state legislation is supporting the drive. The formation of regional arson squads, coupled with local training in fire cause and evidence identification, strengthens the hand of every department, no matter how small.

Coupled with these kinds of prevention programs are state and national efforts to collect standardized fire reports and related information. Already these data are being analyzed and the results fed back in useful format to local departments.

An example of this data feedback system, which is especially important to rural volunteer departments, is the national publicity given to the dangers of wood-burning stoves. We can judge from the many states reporting to the National Fire Data Center the approximate volume and percentage of fires originating from wood-burning stoves and the steps which must be observed if safe conditions are to be met in their installation and use. Manufacturers and distributors of many brands are providing important consumer information and large numbers of volunteer departments in suburban and rural districts are involved in the public education and reporting effort. Not only will wood stove and chimney fires be reduced, but recall of certain stoves for the addition of heat shields and safety equipment has already taken place.

However, very few volunteer departments are engaged in a most important fire prevention function, and that is inspection of commercial property, private residences, and special locations, such as multiple residences, schools, hospitals, and nursing homes. In some parts of the country, state or local laws mandate the inspection of schools and nursing homes by the local department— whether paid or volunteer-—but even this is not universal.

Is it possible for volunteers to conduct inspections as part of a comprehensive fire prevention program? The answer to this key question is “yes,” based on the experience of those who are already doing so.

In essence, there are two basic kinds of inspection programs: (1) those where no codes or ordinances exist to mandate or back up the inspections, so that they become voluntary on the part of property owners; and (2) those where certain codes or ordinances are in existence and inspection is legally required. In the first instance, volunteer departments must depend upon public safety education programs to stimulate an awareness and receptivity to on-site inspections on the part of commercial property owners as well as residents. An active department would be educating citizens in homes and places of work on the advantages of smoke detectors, escape plans, fuel storage dangers and the like anyway, so the connections are often made.

Targeting inspections

Property inspection becomes a logical next step. Places of high hazard, such as retirement homes, long-term care facilities and schools should get careful and early attention. The experiences of many career departments in inspection programs have been described in several publications and provide background information for less experienced departments. Publicity should be widespread, with emphasis on service to the property owner, not “inspection” to cause trouble.

Inspectors or fire prevention officers should be trained, be in uniform, have identification, and travel in pairs, if possible. Often a female inspector teamed with a male inspector may be reassuring to some female residents who are cautious about letting strangers into their homes.

An inspection form and other fire prevention material should be left with the property owner. Questions should be answered, telephone stickers left, and a feeling of public service and concern for life safety should be dominant. The wrong impression made by representatives of the department never may be erased, so volunteer members selected to visit homes and commercial property need good orientation and training for the job. Having new volunteers accompany experienced volunteers is also a good idea.

Two successful programs

What happens in those communities served by a volunteer department where fire codes have been adopted? In almost every instance, the volunteer department advocated the code legislation and stated a willingness to carry out inspections using volunteers. It might be useful to illustrate two such programs which have been operating for years using only volunteers. These examples are but two of several operating in New York State and elsewhere and might serve to motivate other volunteer departments to join in a key element of comprehensive fire prevention.

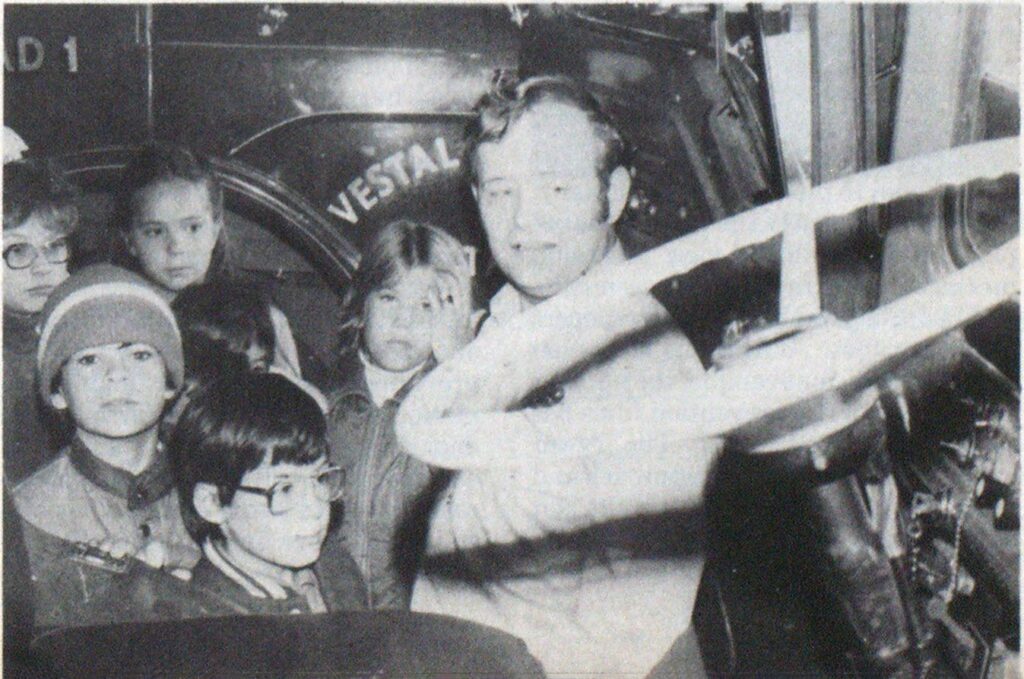

Fire protection for the 27,000 citizens of Vestal, N. Y., is organized under state law as a taxable fire district governed by an elected board of fire commissioners. Stations, apparatus and equipment are owned by the district and served by volunteer personnel. Since the boundary of the Vestal Fire District is identical to the boundary of the Township of Vestal in Broome County, the elected members of the Vestal Town Board serve as the fire commissioners. The highest elected town official is the town supervisor, who is the executive officer of the town government.

The department responded to approximately 325 calls in 1979, protecting property with a value of $600 million. Vestal contains rural areas and builtup residential areas, including garden apartments, bulk petroleum storage facilities, an industrial park, a university, the home office of a large insurance company, two public utilities, a major newspaper and similar structures. A typical busy suburb, there are five large automobile dealerships, 20 restaurants and three motels, for example, within a 3-mile stretch of the major parkway. The highest building is 15 stories and others range from three to 12. The total number of commercial establishments is in excess of 300.

Also organized under New York State law are the Vestal volunteer fire fighters, a membership corporation which provides the people who comprise the Vestal Fire Department. These people are all volunteers, including officers. Emergency medical services are provided by a separate organization, the Vestal Volunteer Emergency Squad, which runs three ambulances.

To provide adequate coverage for the fire district, four stations house a total of eight pumpers, two minipumpers, one aerial ladder truck, one dry chemical truck, three brush trucks, and two heavy-duty rescue trucks. Because Vestal is adjacent to the Susquehanna and Chenango Rivers, two rescue boats are maintained.

The department has approximately 160 active volunteers, including a chief, three assistant chiefs, four captains, and eight lieutenants. The chiefs staff includes the training coordinator, the fire police captain and the fire marshal. The fire police captain leads a squad which provides traffic control and security at the fire scene. The training coordinator has responsibility for the training bureau’s instructors, the training program, and the training school facility, which is used by six other volunteer departments and one career department.

Appointed by town

The volunteer fire marshal, nominated by the chief to the board for a two-year term, is responsible for the fire prevention bureau. This bureau is staffed by a volunteer deputy fire marshal and seven volunteer inspectors. Each is also appointed by the town as a “deputy building inspector.” The responsibilities of the fire marshal and the fire prevention bureau are to conduct inspections of commercial and other properties covered by the AIA fire prevention code adopted by the town in 1969.

Citation of code violations are written up and the time allowed for correction is stipulated. If a violation is not corrected within the time allowed, the town attorney is directed to handle the legal procedures. Since the town also has a building code, and provisions for plan approval, building permits, and construction inspection, the fire prevention bureau works closely with the town building inspectors, who are full-time career employees.

While inspections of the town’s commercial property, schools, and nursing homes are mandated by the code (and by state law in the case of schools and nursing homes) residences are not, so the fire prevention staff advertises the service periodically and inspects home when invited to do so. A fire prevention program for schoolchildren also is carried out by the bureau.

Fires investigated

Besides these duties, the fire marshal and inspectors conduct fire origin investigations. Each is trained in fire inspection work and in fire investigation, and regularly attends courses and workshops. Because each is an active fire fighter, they are expected to attend fires and related training sessions as well. Typically at fires, they begin investigation work upon arrival, unless initial responding units need suppression manpower.

The fire prevention bureau has an office at one of the stations and a telephone answering machine takes calls, which are returned by the marshal or an inspector as soon as possible. The bureau has a departmental station wagon which is used when inspectors conduct their work—always in uniform. In addition to a badge, each carries a Town of Vestal II) card signed by the town supervisor.

The 300 commercial buildings are inspected on a regular basis once each year. Careful records are kept and self-developing photos are taken of serious violations. Property owners or resident managers are asked to sign the report form and call-back inspections are made. Almost always, the reaction of property owners is a positive one because the stress is on education and safety rather than legal proceedings.

Relatively few homes are inspected— and always by request—but the new popularity of wood-burning stoves has increased residential requests manyfold.

Example of activities

It might be interesting for volunteer departments without an inspection program to review the activities of the Vestal volunteer inspectors for a oneweek period during the spring of this year. A review of the monthly activity report indicates the following:

- Inspection requested of a residence.

- Inspection of a construction site where an excavating machine found an abandoned gasoline storage tank. (The excavator was pleased to discover that there were 900 gallons of gasoline remaining. When the fire marshal checked old maps, he identified the site as a former country club, leveled more than 15 years earlier.)

- Notification of plumbing work at a bulk petroleum storage depot.

- Called by a resident who discovered his fuel oil tank leaking.

- Attended town board meeting and advised on hydrant location for planned minimall shopping center.

- Inspected commercial properties and discovered a combustible heat duct in one.

- Received inquiries from out-oftown contractor concerning where air tanks could be filled.

- Obtained letters of consent from nonresident owners of shopping center concerning demarcation of fire lanes. Prepared proposal for town board.

- Received request to check out living quarters located over commercial property.

To gain the most from the inspection program, the fire marshal meets with the town planning board each month as a nonvoting adviser and with the fire department officers each month to review his report and provide information for pre-fire planning.

The current fire marshal, William Oliver, recalls that the fire prevention bureau, which now operates on a $1200 annual budget, was formed when a 1965 ISO review pointed out that with 200 additional points, the department would move up one classification and that the creation of a fire prevention unit would accomplish that.

When Oliver is asked if the program is stopping fires, he responds, “It’s got to be!”

Smaller town’s system

How comprehensive a program is possible in a smaller community? Located also in Broome County, N.Y., is the hamlet of West Corners. The total population protected by the two stations of the West Corners Volunteer Fire Department is 6000 within an area of 6 square miles. The department runs three first-line pumpers, an elevating platform, a brush truck, and a heavyduty rescue truck. The 45 active volunteer members responded to approximately 70 alarms in 1979. They protect rural and builtup areas, and they inspect 50 commercial buildings, some within a shopping center, a large shoe manufacturing factory, a high technology industry which employs 2800 on three shifts, two schools, and several banks and churches.

If you were to dial the number listed in the telephone directory under West Corners Fire Prevention Bureau, you would hear the recorded voice of Fire Marshal John Kratochvil say, “Hello. This is the West Corners Fire Prevention Bureau. Please do not report a fire to this recording. This is for your information so that we may assist you. If you wish us to contact you, please leave your name, address, phone number, and your message. We will return your call as soon as possible. Thank you for calling.”

The recorder is checked once or twice each day.

Inspectors rotated

The bureau is staffed by the fire marshal, an assistant marshal, and six inspectors, all volunteers. Those whose regular job has them working a night shift conduct the daytime inspections, and the size of the community enables each commercial property to be inspected every six months. After two or three inspections of the same property, an inspector is rotated to other properties.

Inspectors arrange their own schedules, inspect in business clothes, and each carries a badge and a photo ID card signed by the chairman of the elected board of fire commissioners. Inspectors go out in teams of two, and a running folder is maintained of each property inspected under the AIA code.

The West Corners bureau was formed in 1964 and operated a totally voluntary inspection program until the AIA code was enacted into law by public referendum in January 1972. With the emphasis on life safety and loss of business due to fire, legal proceedings have never been needed, since all violations have been corrected within the stipulated time period. Many return inspections are conducted within 24 hours. Interestingly, some establishments are requesting inspections every three months rather than every six. Each inspection form calls for a pre-fire plan sketch on the reverse side.

Direct feedback is used for pre-fire planning and company officers sometimes are given a walk-through by an inspector. For example, the inspectors realized that there would be vast differences in fighting a fire at the shoe factory during working hours and when it is closed at night. Therefore, day walk-throughs were given to small groups of fire fighters.

Requests for residential inspections are on the increase, along with some insurance company requests. A recent request came because the supply company delivering oxygen to an invalid asked the homeowner to call. Because the current work load is manageable, the bureau is planning a more intensive advertising campaign to encourage homeowners to request inspections, and will launch this drive during Fire Prevention Week.

Fire records and the national reporting system forms are filled out by the bureau staff and all fires are investigated by them. Each has been trained in both inspection and investigation work at the New York State Academy of Fire Science. All bureau members are fire fighters first and must complete the mandated annual training hours and respond to 50 percent of the fire runs which are made when they are not working at their regular jobs. While West Corners has women fire fighters, the bureau is still seeking its first woman inspector.

Building plans reviewed

A carefully worked out arrangement with town officials has the fire prevention staff reviewing building plans. Building permit documents are sent to the marshal each month, and any new development of more than three houses must be reviewed by the chief officers as well. The town building department’s position is that it would rather have the fire department review plans before construction than to complain after, and the marshal agrees.

The bureau’s program is comprehensive, with public education programs, school programs, extinguisher training for local groups, and an extensive 4-H fire safety program run by the department for the last five years. The $600 budget buys fire prevention material, films, phone and invalid stickers, arson investigation equipment, forms and office supplies, and equipment, such as the phone recorder and an explosive vapor detector.

In each of these volunteer programs, much thought has been put into the design and much time put into the task.

But as Marshal Kratochvil put it, “If we’ve saved one life, the time’s worth it.”

References:

- Research Triangle Institute, et al, “Municipal Fire Service Workbook,” U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., p. 94.

- Ibid, p. 94.