BY HIDEKATSU KAJITANI

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1021, Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications, 2014 edition, categorizes fire service officers into four levels, which follow:

- Fire Officer I-supervisory level.

- Fire Officer II-supervisory/managerial level.

- Fire Officer III-managerial/administrative level.

- Fire Officer IV-administrative level.

Another common distinction is line officers vs. staff officers. There are some discrepancies among jurisdictions. However, most jurisdictions describe line officers as ranks below the battalion chief level including captains and lieutenants. Line officers are often assigned to 24-/48-hour shift rotations, while staff officers are administrative chief officers who often work a “normal” schedule of 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., five days a week. Staff officers include the chief, deputy chief, assistant chief, division chief, district chief, and so on.

When a fire officer seeks promotion or new employment, the NFPA’s categories are useful because they provide clear sets of national standards that demonstrate the competencies of an individual who has achieved a certain level of fire officer standard. The distinction between line and staff officers helps us to understand the roles each performs.

Officer Types I-IV

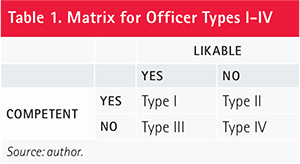

Another category of fire officer found across the nation but not as well recognized as fire officers and line or staff officers is based on two characteristics we hope to find in fire service officers: competency and likability. The typing of these officers follows:

- Type I-officers who are competent at their job skills and are likable to their coworkers, superiors, and subordinates.

- Type II-officers who are competent at their job skills, yet they are not likable.

- Type III-officers who are not competent at their job skills and are well-liked among the troops.

- Type IV-officers who have no competency and no likability (Table 1).

Modern fire departments are organizations of customer service; unfortunately, many fire service personnel are new to this concept. On the other hand, the business community has been researching the customer service concept for quite some time. Luckily for us, the business community has also been examining the exact same concept; they just don’t call their officers “chiefs,” “captains,” and “lieutenants.” In the business world, they are called “executives,” “managers,” and “supervisors.”

Business Community Research

Research from business communities shows that everybody wanted to work with the “lovable star” (Type I officer) and nobody wanted to work with the “incompetent jerk” (Type IV officer). This finding is very logical and leaves no doubt as to what type of officer members want on their apparatus or at the station working with them. If your organization has Type I officers, their presence is valued, they have respect from others, and the organization should place these officers as role models. If your organization is unfortunate to have one (or even several) Type IV officers, it is not the end of the world; training programs, mentorships, and many other prevalent forms of “officer development” programs improve competency for fire officers. As I will discuss later, likability is much more difficult to improve than competency.

If Type I and Type IV officers are in the “clear” area-i.e., organizations and fellow firefighters know which type to praise and prefer-Type II and Type III officers are definitely in the “gray” area because much business research has found that overall preference tends to go to a person’s likability rather than competence and ability. This social phenomenon in which an office worker prefers to work for a boss who might be slightly incompetent but fun to work with is easy to understand. In other words, a little extra likability goes a longer way than a little extra competence in making someone desirable to work with.

So, what does this mean for us? Business research shows that members prefer to work with Type III officers more than Type II officers. Is this what firefighters should prefer? This means that firefighters prefer an officer who is very easy to get along with and has an awesome sense of humor at the firehouse but lacks competency in performing his duties as a fire service officer. Is this the officer you want to see leading a rapid intervention team (RIT) while you are inside a burning structure? Firefighters should prefer on their RIT an officer who is competent in aggressive down firefighter search and air management skills, not “the lovable fool” who makes you cry laughing while hanging out at the firehouse.

Another disturbing finding from the business community’s research shows that the lack of likability in an executive often suppresses others’ abilities to subjectively assess his competence. In other words, a very competent fire officer might not be used in an organization because the officer is slightly lacking in the social skills needed to be liked by others. This is a great waste of human resources by an organization and may result in safety issues by placing incompetent officers over competent officers.

An additional twist exists within this subject on the relationship between competency and likability for female officers. In a study of gender and social influence, research shows that “men responded more favorably to a woman who communicated in a relatively incompetent style.” Similar findings reported in an article that explored women’s likability in employment negotiations in Australia explained that “professional women who engage in proactive competitive behaviors may be perceived as more competent, but the attribution of competence is likely to be accompanied by a decrease in perceived likability.” Another study looked at female politicians Hillary Clinton and Sarah Palin during the 2008 presidential election and brought up the possibility that “women are either seen as likable, but incompetent, or as competent, but unlikable.”Thus, female officers in the fire service face dilemmas between competency and likability; one inversely affects the other, making it difficult for females to be competent and likable in the eyes of their fellow firefighters.

Possible Solutions

Now that you understand the problems regarding Type II and Type III officers, what is the solution? First, assess your organization with regard to chief officers, line officers, or any other subordinate ranks to see which types of officers your department has. Few organizations in this country will be filled with Type I officers. Identify your Type II officers so that their skills and knowledge can be explored to the fullest and you can work on improving their likability. Identify Type III officers so that they can improve their competency as fire service officers while maintaining their likability. Last, if your organization has Type IV officers, determine why those members were promoted to the rank of officer.

Fire service organizations can tap into strategies used in the business communities. Use these organizational strategies that address issues involving Type II and Type III officers to create and leverage their likability, improve the competency of other fire service officers, and address the unlikable officers. Create an environment in your organization that will protect existing likability and increase or even create likability. An organization can also promote familiarity; psychological studies show that people are more likely to prefer what is familiar to them. Comfort in interacting among people usually increases with regular exposure to others. The fire service implements this concept by conducting multicompany drills and other such activities that bring together members who are familiar with each other. Business communities accomplish this by designing office space in a manner that maximizes exposure to other coworkers.

Another method organizations use to create and promote likability is redefining their similarities. Business communities accomplish this by restructuring or relabeling different groups of employees as a single group. For example, a marketing and research and development group can be combined as a “Product X” group instead of just by their specialties.

A final method business communities implement is fostering bonding among employees. Business communities have many strategies to make this happen; one involves putting their employees through intense cooperative experiences. Fortunately for firefighters, that’s exactly what we do at the scene of an emergency-we work together to accomplish shared goals as a team in very intense environments.

An organization should use its likable officers-Type I and Type III-as bridges between people who are not otherwise interacting. Likable officers can do this because they tend to have sophisticated social and interpersonal skills, attractive personality traits, and chemistry. These bridging officers create an environment for members who otherwise would not be eager to work together to engage in activities to increase their “face time,” thus increasing familiarity, which will eventually and hopefully lead to likability. Unfortunately, an organization may not recognize the effectiveness of these bridging officers until they leave the organization because of a change in assignment, retirement, and even termination or layoff. It is important for your organization to protect these officers to maintain an environment that promotes likability.

You must also strategically place these bridging officers on a “specialty team” within your organization to increase opportunities to bridge members who might otherwise resist. These teams might be formal task forces such as technical rescue teams, regional strike teams (such as water tender strike teams), or an administrative group such as a fire prevention committee. Team formations might be one of your few options to place these bridging officers in the unionized environment, which makes positioning these personnel extremely difficult.

It is crucial to implement solid initial, formal training and in-service training to improve fire officers’ competency. Physicians “practice” medicine because, in their field, there is no end to learning and improving; the same should go for the fire service. A committee within the NFPA has worked over the years to provide us with nationally acceptable standards for fire service officers. The burden is now on officers to uphold those standards and seek constant improvement and maintain proficiency throughout their careers. Improving competency is not only for Type III and Type IV officers but also for those officers who currently meet competency set forth by their positions within organizations.

Last, an organization must not ignore contributions by its unlikable officers; this will often result in missed opportunities because an organization often fails to explore these officers’ expertise. If the contributions of unlikable officers are important to your organization, help make these officers more likable. Behavior modification of adults is complicated and not usually a specialty found in the fire service. Instead of seeking to dramatically change these officers, attempt to turn them from unlikable to “tolerable.” Business communities use coaching methods that immediately address an individual’s negative behaviors after an incident instead of later in an annual performance evaluation. Repositioning is another method used to address the issue of unlikable officers. If a position in your organization has limited interaction with other members and the public, Type II officers’ expertise might be best served in those positions if their likability cannot be easily improved.

Evaluate Yourself

These classifications exist not to replace our current officer classifications but to improve our roles as fire service officers. What type of officer are you? Carefully and honestly evaluate your competency and likability. Likability should not interfere with the promotion process, which consists of an interview and a written exam but rarely assesses likability. Competent candidates may be getting passed over for promotion by less competent colleagues because of their lack of social skills. Even though social skills and likability are important traits of effective fire service officers, decision makers should not overlook technical competency. Business communities explored these traits in their executives to improve their performance, efficiency, and competition over rival companies.

Fire service organizations can also benefit from this research’s positive impact on life safety. In certain instances, having more Type III officers than Type II officers can result in life or death for those who work under them. Businesses can lose money, time, and products as a result of poorly placed managers. The stakes are too high for us to use our officers in this manner, especially during so-called high-hazard/low-frequency incidents.

Fire service officers are now classified into these four categories, and these categories can be applied easily to our nonofficers and new recruits. Some nonofficers are very competent; their personalities and skills are well-liked by fellow firefighters and officers, while others who lack competency will not be liked by anyone. Organizations need to type their nonofficers; they will ultimately become the backbones of these organizations. After all, one important and oft forgotten duty of fire service officers is to prepare the next generation of officers to join their ranks. There is no reason to wait to promote them to assess their type. When I was a new firefighter, my officers taught me the importance of integrity, pride, and dedication. Nonofficers will carry on what you were once taught when you were in their position.

ENDNOTES

Casciaro T and MS Lobo. “Competent Jerks, Lovable Fools, and the Formation Social Network,” Harvard Business Review. June 2005.

Carli LL. “Gender and Social Influence,” Journal of Social Issues. 57(4), 725-741. 2001.

Kulik CT and M Olekalns. Competent and Likable? Protecting and Promoting Women’s Likability in Employment Negotiations. Presented at the Academy of Management meeting, Chicago, IL. August 2009.

Schneider AK, Tinsley CH, Cheldelin SI, et al. “Likability v. Competence: The Impossible Choice Faced by Female Politicians, Attenuated by Lawyers,” Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy, 17(2), 10-42. 2010.

Willis J and A Todorov. “First Impressions-Making Up Your Mind After a 100-Ms Exposure to a Face,” Psychological Science, 17(7), 592-598. 2006.

Winston R. “Is Likability an Essential Element of Leadership and Management?” PM World Today, XIII(III). March 2011. Retrieved from http://pmworldtoday.net.

www.jobrecruiting.com/workplace-issues/likability-competence-in-the-office.

HIDEKATSU KAJITANI, MS, NREMT-P, is a captain of special operations for the Sugar Creek Fire Department (SCFD) in Vigo County, Indiana. He has bachelor of science degrees in criminology and psychology with minors in sociology and political science and a master of science in criminology from Indiana State University. Kajitani also served as a fire investigator for the SCFD and is a hazmat technician for the county’s hazardous materials response team. He is also a petty officer for the U.S. Navy Reserves assigned to Expeditionary Medical Facility Great Lakes One-Detachment R in Indianapolis, Indiana.

A Day in the Life of a Company Officer

Officer Development: Training Officer’s Toolbox: Influence

Officer Development: Training Officer’s Toolbox: Assertiveness vs. Aggressiveness