As firefighters, what we do on a daily basis plays a large role in cancer prevention. We eat right, exercise, use source capture to keep diesel exhaust out of our stations, and follow best practices that lead to a healthy workplace. All of this is an important part of the equation, but we must also look closely at what we do immediately following a fire to keep the cycle of prevention going. It all starts with understanding the importance of contamination control.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Reducing the Postfire Threat of Cancer

Respiratory Protection in the Warm Zone: A Study

Creating a Cancer-Resistant Fire Department

Firefighters should learn from the science that has been conducted to find solutions to the cancer epidemic we face. We also need to adopt policy based on what we learned. I have been asked, do we really need to make these changes? Well, that’s a good question, so let’s look at that and how you can get started with some simple items that only cost a few dollars but work to keep a large portion of the fire contaminants at the incident scene.

Why We Need Postfire Decon

To understand why, we need to look no further than the research conducted by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). They have examined the incidents of cancer and the questions around fireground contamination. NIOSH research shows that firefighters are exposed to many carcinogens during firefighting activities. These include known and suspect human carcinogenic toxicants like polycyclic aromatic-hydrocarbons (PAH) such as benzo[a]pyrene, asbestos, formaldehyde, benzene, and 1,3-butadiene along with many other probable or possible human carcinogens. These compounds attach to our equipment during fires through contact with products of combustion or what we call smoke (photo 1). You should avoid this toxic soup of hundreds of compounds, if possible. Of course, firefighters will find it impossible to avoid every exposure, so we must be aware that our gear has become contaminated and needs to be decontaminated in a process that will remove as much of the contamination as possible.

(1) Photo by Ioanna Raptis; photos 2-4 by author.

In 2017, research demonstrated that firefighters could use simple methods such as soap and water in a field decontamination model to reduce the contaminants (PAH) by 85%. This is becoming a standard practice for many fire departments across the nation as a way to reduce exposure and leave the toxicants behind.

The Decon Method

Several methods of decon are offered through research. Wet soap decontamination proves to be the most effective. Adopting this as a primary decontamination process will give you the best results. However, in my climate, where it can routinely get extremely cold, wet decontamination may not be practical every time. Having a second option of dry decontamination provides some level effectiveness, but research shows that wet soap decontamination provides the best level—around 85% reduction as compared to a 23% reduction with dry decontamination.

Wet soap decontamination consists of using a detergent solution and water to wash off the contaminants. The process is quite simple and takes little time. A solution of dish detergent and water [10 milliliters (ml) in two gallons] is applied to the gear and then the gear is brushed to loosen the particulates, followed by a rinse down with clean water to remove the contaminants. This really can be done in any weather; however, places where freezing temperatures are a concern may need the option of dry decontamination, but it is not as effective. Dry decontamination is simply brushing off the particulates that are on the turnout gear.

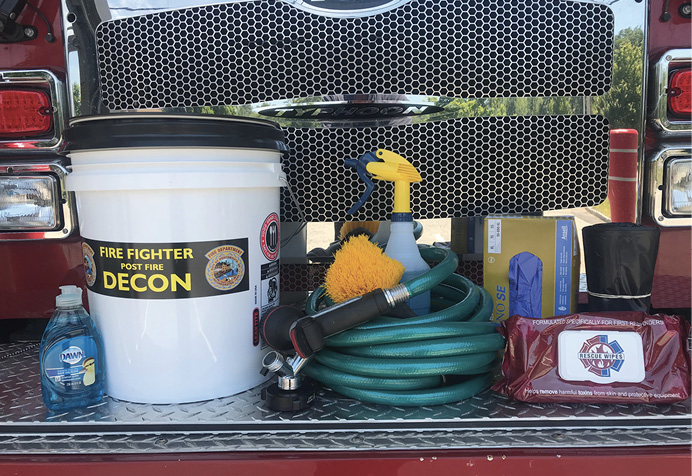

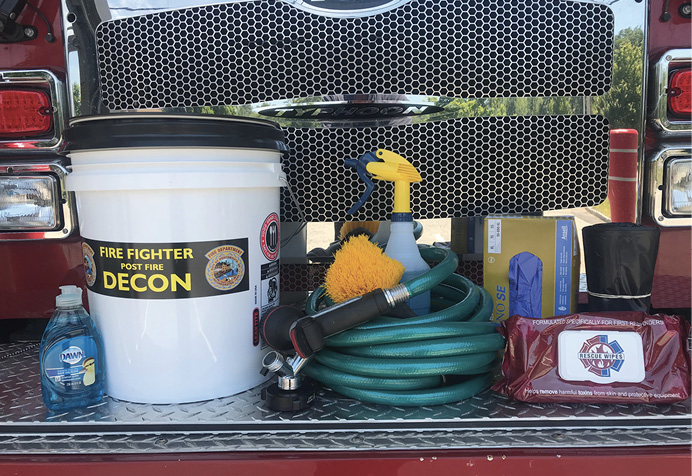

The Decon Bucket

In the Portsmouth (NH) Fire Department, our decontamination bucket starts with a standard five-gallon bucket and lid (we used screw-top lids for ease of access). This is a convenient place to store the items needed and a place to mix a cleaning solution, too. You can assemble this all for under $100. Inside the bucket are the following items: 25 to 50 feet of garden hose, a garden hose nozzle, a 1½-inch garden hose adapter, a scrub brush, a spray bottle with solution, a bottle of dish detergent, a package of wipes, six large trash bags, and a box of XL nitrile gloves (photo 2).

(2)

Setting Up the Decon Area

The apparatus operator (when time allows) should establish a decontamination area 20 to 30 feet upwind from the contaminated area and 20 or more feet from the apparatus. Start by placing a traffic cone as a marker. Then connect the hose to a discharge and stretch out the hose, adding the nozzle. Place the bucket with the detergent spray and brush by the cone where members entering the decontamination area can see them. Also, place a box of nitrile gloves in this location for members to use. Then, pressurize the hose, keeping in mind not to exceed 80 pounds per square inch (psi) at any time; 40 psi is adequate. Mix about 10 ml of detergent in two gallons of water in the bucket. There is also a premixed bottle of spray we can use if only a few members are being deconned.

Firefighter Decon Steps

Firefighters should start by practicing good air management, thus allowing members to remain on air during the initial decontamination. It is understood that staffing and operations may not allow a decontamination process between cylinder swaps; however, we know that it takes nearly 24 minutes for the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) to evaporate from the gear, so remaining on air, if possible, is a good prevention tactic. When using dry decontamination, remaining on air is important because loosening the particulates will cause them to become airborne and inhaled.

Working with a partner, rinse off starting at the top (helmet) and working down (photo 3). Then spray on or lather up with the detergent solution from the bucket (10 ml dish detergent in two gallons of water) on the contaminated gear. Use the brush to scrub any obviously soiled areas, then rinse off the gear starting at the top and again working down. If performing dry decontamination, use the brush to remove any obvious particles and scrub soiled areas.

(3)

When both members are rinsed, remove your gloves, taking care to not contact the outside. Use wet towels or decontamination wipes. It is recommended that you wear nitrile gloves for the remainder of the decontamination process.

Next, remove the helmet, followed by the hood and mask at the same time, pulling the hood over your head inside out. This will keep the contaminants that are on the outside of the hood off your skin, reducing exposure. Remove your coat if weather allows.

Research shows that dermal absorption is another contributing factor of exposure. It further demonstrates that PAH exposures on our hands may have as much as four times the PAH contamination as compared to the necks. This makes the next step critical to the process.

Use wet towels or decontamination wipes to clean the neck and hands prior to proceeding to the rehab area or ingesting anything to remove a great deal of the contaminants (photo 4). Some really creative departments have made warm water wash stations on their apparatus. This is a great idea and could easily be replicated for little cost. Check out the “Healthy In, Healthy Out” resource from the Washington State Fire Council.

(4)

Once you have completed gross decon, it is important to make every effort to keep the remaining contaminants from making their way into your system. This takes us back to the firehouse to completely decontaminate in the shower and change clothing. Showering with a water temperature that is comfortable for you is best in my opinion. No one wants to take a cold shower or one that is superhot. It is as simple as washing well enough to remove all the soot from your skin to stop any absorption. Remember, all skin—even skin covered by your gear—could be contaminated, so get in every nook and cranny.

Keeping the Cab Clean

Before we head out to the station, we should think about the apparatus we arrived in and how we can minimize carrying the contaminants back with us. Large trash bags (use clear bags) are in our decon bucket to aid in keeping the contaminants out of our apparatus. It is part of a system that gets gear from the scene to the extractor for advanced cleaning. It may be beneficial to consider transporting gear in a utility truck instead of in the apparatus cab; however, this may not be an option for all departments. The goal is to keep the apparatus cab as clean as possible.

When firefighters remove their gear in a manner to limit skin exposure following postfire decon, they can place that soiled gear in the bags and tie or seal the bags to transport them back to the firehouse without getting the contaminants in the cab. It may be best to place the bags in an outside compartment or the hosebed, but many I have spoken with have a concern that they will need the gear if they are called to another job while returning to the station. Of course, the goal is to get back in service completely before being assigned to another job, but it is understood that this is not possible for every department. Bagging gear does not replace the need to clean the cab after the incident, as there are many times when the contaminants in the air can make their way into the cab on the scene. A clean cab is essential to a good program of managing exposures.

It’s important for all firefighters to keep contamination under control. A good contamination control program coupled with a good health and wellness program will go a long way toward reducing firefighters’ risk of cancer. It really is as simple as taking steps every day to reduce that risk, whether it be cleaning the cab of the apparatus, maintaining clean protective equipment at all times, ensuring that your air management skills are good, following recommended postfire decontamination procedures, or staying up-to-date on the most current research. Most importantly, it starts with you advocating for everyone in the department to follow through with the recommendations.

Resources

Daniels, R. D.; Kubale, T. L.; Yiin, J. H.; Dahm, M. M.; Hales, T. R.; Baris, D.; and Pinkerton, L. E. (2014). “Mortality and cancer incidence in a pooled cohort of US firefighters from San Francisco, Chicago and Philadelphia (1950-2009).” Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 71(6), 388–397. doi:10.1136/oemed-2013-101662.

Fent, K.W.; Alexander, B.; Roberts, J.; Robertson, S.; Toennis, C.; Sammons, D.; Bertke, S.; Kerber, S.; Smith, D.; and Horn, G. (2017). “Contamination of firefighter personal protective equipment and skin and the effectiveness of decontamination procedures.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 14:10, 801-814, DOI: 10.1080/15459624.2017.1334904.

https://www.wscff.org/health-wellness/healthy-in-healthy-out/.

RUSSELL OSGOOD is a career firefighter with 30 years of experience, the past 22 years with the Portsmouth (NH) Fire Department. He is a staff instructor with the New Hampshire Fire Academy. He coordinates the Statewide Cancer Awareness & Prevention Program. As the Firefighter Cancer Support Network New Hampshire state director, Osgood was instrumental in developing the NH State Cancer Prevention Initiative. He serves as co-developer and key instructor for the “Taking Action Against Cancer in the Fire Service” national cancer prevention program.