BY JEFFREY A. HARWELL

Whenever there is a large-loss fire anywhere in the United States, fire service leaders and fire protection specialists immediately begin to scramble to determine what went wrong. Often, these high-dollar facilities are protected with state-of-the-art fire protection systems that are supposed to prevent such outcomes.

- Fire in Sprinklered Texas Warehouse with High Piled Storage

- How Does a Fully Sprinklered Warehouse Burn to the Ground?

- Fire in a Fully Sprinklered Building

- Fighting Fire in Sprinklered Buildings

When a large-loss fire does take place, you can be pretty certain it will have lessons to be learned from studying the fire. With the advent of the early suppression fast response (ESFR) sprinkler systems, most people would like to know if a particular large-loss fire involved this type of system.

On June 6, 2020, in Redlands, California, some 58 miles east of Los Angeles, an early-morning fire destroyed a 600,000-square-foot warehouse, resulting in a loss of more than $200 million. The entire facility was protected by an ESFR sprinkler system, making it an ideal fire to study and discover lessons to learn related to ESFR sprinkler systems.

The Fire Building

The fire building was at 2255 West Lugonia Avenue in northwest Redlands. The building’s A side (north) faced West Lugonia Avenue and the C side faced Interstate 10 (I-10). Personnel doors provided the only building access on these two sides. The B and D sides each featured 48 roll-up doors for tractor trailer loading/unloading. A fire lane circled the building on the B, C, and D sides. The main warehouse area’s overall dimensions were roughly 615 feet (A/C side) by 937 feet (B/D side). The warehouse acted as a third party in the distribution chain for Amazon.

The building construction featured tilt-up concrete walls and steel columns supporting a steel truss/girder system, topped by a built-up roof over an exposed plywood roof diaphragm. There were 4- × 8-foot skylights with fixed plastic lenses placed throughout the roof structure. Fifteen roof-mounted exhaust fans were part of a nonrequired smoke exhaust system. Intake louvers were situated along the exterior walls near the roofline above the roll-up doors.

The automatic sprinkler system protecting the building featured ceiling-mounted sprinklers fed by 16 separate systems. There were no in-rack sprinklers. Based on the initial plans, rack storage was permitted up to 34 feet high; palletized storage could not exceed 24 feet. The permissible storage height was 40 feet. The building was 45 feet high at the peak.

The sprinkler system was designed to meet the standards of an ESFR installation. Systems such as these were first introduced in the late 1980s. Building owners favor it because it reduces the need for in-rack sprinklers, and it appeals to the fire service because (as the name implies) it provides an opportunity for extinguishing a fire prior to the fire department’s arrival. This could possibly negate the need to fight a fire that could be 30 to 40 feet above the finished floor.

A 10-inch private fire main encircled the building and was connected to the public water main along West Lugonia Avenue at two locations. Each of these connections featured an aboveground control valve assembly. A 2,500-gallon-per-minute (gpm) fire pump was in a separate, detached building in the parking lot near the building’s A/D corner. The 10-inch private fire loop supplied nine yard hydrants on the B, C, and D sides.

The building had an addressable fire alarm system that mainly monitored the sprinkler system’s waterflow and supervisory devices. Two horn/strobe devices in the building were in the building’s A/D corner, one adjacent to the fire alarm control panel in the electrical room and the second horn/strobe and the remote annunciator located a few feet from the main entrance. A single manual pull station was adjacent to the remote annunciator.

The Fireground

At 5:23 a.m. on June 6, the alarm company received a fire pump running signal, followed by a fire alarm control panel pull station activation one minute later. Two seconds later, System 8 signaled a waterflow switch alarm activation in the area where the fire is believed to have originated.

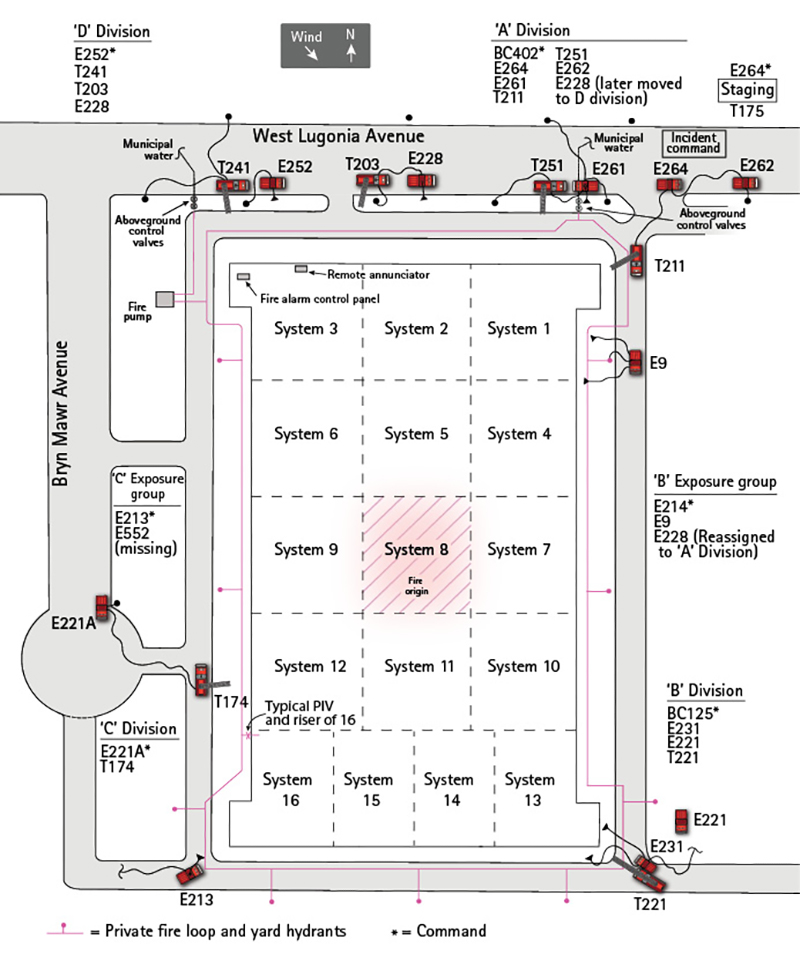

Figure 1. Apparatus Deployment

(1) Photos 1-7 show the rebuilt warehouse, which is of the same design as the original. This is the C/D corner looking east along the 615-foot C side exterior wall. Once building collapse became an issue, firefighters lost access to the C side because the fire lane was within the collapse zone. All private fire hydrants on the site were painted red and served by the 10-inch private main fire loop. These hydrants were ineffective early in the fire because a large number of sprinkler heads/zones were operating. They were rendered completely useless when the two control valves connecting it to the municipal water system were closed. (Photos by author unless otherwise noted.)

(2) This is near the A/D corner looking east along West Lugonia Avenue. The fire lane between the fire building and the boulevard was also within the collapse zone, which forced aerial apparatus to line up along West Lugonia Avenue, further limiting the reach of master streams. The aboveground control valve at the lower right of this photo was the second control valve from the municipal water supply that would be closed later in the incident. Water conditions improved significantly on the fireground after the second valve was closed, since there were no longer large amounts of water flowing out of the 16 sprinkler risers.

(3) This photo was taken near the A/B corner facing eastward. The building in the background was identical to the fire building; investigators surveyed that building when assessing whether the fire protection systems were designed properly. The aboveground control valve in the lower right of the picture was closed early in the incident to try to conserve water but was not too successful; the second connection was still open at the time.

(4) This view is looking down the B side from West Lugonia Avenue. On the morning of the fire, a number of trailers were backed up to the overhead doors. None of the remaining overhead doors were open, which meant they would require forcible entry. Initial efforts to gain access to the warehouse interior were made near the A/B corner, on the right of photo. Fire was observed in all the ventilation openings above the overhead doors early on in the incident.

(5) This view looks down the D side from West Lugonia Avenue. Command established a B and C exposure group to protect the trailers backed up to the overhead doors. The C exposure group was actually operating on the D side since the C side had no trailers or exposures. The fire pump house is on the right side of the photo.

At 5:26 a.m., the CONFIRE Communications Center dispatched a first-alarm response consisting of Engines (E) 264, 261, 263, 231, and 252; Battalion Chief (BC) 704; and Squads (SQ) 264 and 263 for a reported fire in a warehouse. En route to the fire, BC704 reported smoke showing while responding on I-10. Because no truck company was on the first alarm assignment, BC704 special-called Truck (T) 251 at 5:39 a.m. On arrival, the chief reported a large commercial wide-rise structure with heavy fire and smoke showing; evacuation appeared to be in progress.

BC704 established command on West Lugonia Avenue near the A/B corner and advised E264 to make a 360° survey around the building to determine the best point at which to access the building and initiate a fire attack. Before E264 could complete the survey, command determined that most of the fire was on the warehouse’s B side near the A corner. E264 was redirected to enter the building at this location and attack the fire.

Next-arriving E252 and E263, along with SQ264, were teamed up with E264 to get a roll-up door open and stretch a large handline to attack the fire. E261 was directed to find the fire department connection (FDC) and augment the sprinkler system. At this point, it was reported that all B side roll-up doors appeared to be closed, and fire was observed coming out of every B side ventilation opening.

Because of the building’s enormous size and the rapidly advancing fire, command immediately called for second and third alarms. The second alarm dispatched at 5:39 a.m. consisted of E221A, E221, E262, Brush 264, T221, and BC125. The third alarm dispatched at 5:42 a.m. and consisted of E214, E228, E9, E213, T211, and BC211. With the immediate need for additional elevated master stream devices, all available ladder trucks in the county were special-called; this request was filled at 5:46 a.m. with T241, T203, T174, and T175. At this point, seven trucks in all had responded or were en route.

While the initial handline was still being stretched, part of the roof collapsed, so command sounded the tone for operational retreat. The fireground strategy switched to defensive (Figure 1); the goal was to set up an aerial master stream at each corner of the warehouse. However, command had to rely on mutual-aid ladder trucks that took longer to arrive because of extended response times as additional alarms were sounded. Battalion chiefs were also in short supply in this part of the county, so they had longer response times. As a result, some sectors were eventually assigned to fire company officers.

(6) This aboveground control valve connecting the private fire protection water system with the municipal water supply is properly labeled with one exception. The signage should state that this valve is “1 of 2” serving the given address. If fire overtakes the sprinkler systems, both valves will need to be closed to increase pressure in the municipal water system in the area. During the fire, crews were not aware of the second control valve until later in the incident.

(7) This shows the B side of the warehouse from the cul-de-sac at the end of Bryn Mawr Avenue. When the water supply to the yard hydrants was shut down to conserve water, most units operating at the structure’s rear had difficulty maintaining a positive water supply. Since the street had a municipal water main, an engine company was able to set up on it and supply T174, set up inside the gate at the right of the photo.

Since the warehouse was now almost fully involved, attention turned to identifying and protecting exposures. There were a large number of trailers along the B side and some of them were now starting to ignite. Command created a B exposure group to attack these new fires and assigned three engines to this task. A C exposure group was established to protect the trailers that lined the opposite side of the warehouse. Although this group was called the C exposure group, the trailers were actually lining the D side of the warehouse. This group was also responsible for protecting a fuel tank discovered on the D side.

Aside from the initial minutes of the incident, the fire was fought totally from the exterior with one exception. Some corner offices were not heavily damaged during the fire. It was decided to briefly allow a firefighter team to enter these offices to retrieve surveillance video disks that might assist investigators in determining the fire’s cause.

Discussion

Sector Designations/Accountability

One issue during the early stages of the fire was that most companies were operating at the warehouse’s corners, leading to the dilemma of establishing sector command using the alphabetic designation method. When the D division was established, its units were actually operating on the warehouse’s A side. When E228 was reassigned to the A sector and relocated to West Lugonia Avenue, it parked directly in front of T203. Although these two units were only a few feet apart, E228 was assigned to the A sector and T203 was assigned to the D sector.

Another factor that played into accountability was the fireground’s size; the command post was almost 1,200 feet from the remotest corner of the building. In a situation like this, it’s imperative that fire crews help the incident command team accurately provide and maintain sector designations so that additional incoming units can efficiently report to their assigned task. More importantly, if something goes wrong, history has shown that mistakes made with the sector designations can have disastrous results.

Because of Redlands’ location within the county, very few battalion chiefs were available to draw on for dispatch to this fire. As a result, very few battalion chiefs were on the fireground during the early stages of the fire. Eventually, certain sector assignments had to be assigned to company officers. It is critical to establish and assign sector commanders as early as possible in an incident for consistent accountability from the onset. This issue is discussed further under “Resources.”

Designating a safety officer is important in any fire, especially during a large-scale incident such as this. Here, crews assigned to exposure protection had a difficult task preventing the fire from spreading to trailers that were backed up to the warehouse. Most of the B and D side walls remained upright throughout the incident. Since the trailers backed up flush to these upright walls, there was no way to place a hose stream between the warehouse and the trailer. Attempting any fire attack on the trailers when they started to burn would usually put firefighters within the collapse zone.

(8) Among the most important factors in the fire’s incredibly rapid spread, this switch controlled the smoke exhaust fans, which the fire code did not require. The key to the switch has been broken off, so the fans remained operating in exhaust mode. The city of Redlands/Office of the State Fire Marshal investigation reported that an employee had told the investigative team that the fans were being used for environmental air. [Photos 8-10 courtesy of the Redlands (CA) Fire Department.]

It’s important to assign a safety officer as early as possible to ensure companies are not operating in the collapse zone even when units are operating defensively. Departments should have a plan to quickly fill this position with on- or off-duty personnel. A fireground as large as this one may need more than one safety officer.

With a defensive fire, incident command may not think about conducting personnel accountability report (PAR) checks as part of the accountability system. But what if the fireground takes up more than 13 acres? Logic would indicate that there are no accountability issues since units were operating defensively outside. But as this fire demonstrated, that may not always be the case.

In addition, E552 was assigned to the C exposure group. Some later time, the exposure group commander recalled that he was supposed to receive E552 in his sector, but that unit never reported to him. Thus, E552 was unaccounted for on the fireground during that time.

Water Supply

At one point early in the incident, E261 reported they had supply lines tied into public hydrants on both sides of West Lugonia Avenue and still had only 40 pounds per square inch (psi) of pressure. Companies hooking up to yard hydrants reported only 30 psi. As the warehouse quickly became fully involved, all 16 sprinkler systems were operating or damaged, thus creating a tremendous drain on the private fire loop and the city water grid in the area.

At one point, the control valve from the city main to the private fire loop at the warehouse’s A/B corner (directly adjacent to E261) was closed to determine if this might improve the overall water pressure on city water mains; it did to a degree. Later in the fire, the water department determined there was a second control valve between the city main and the private fire loop at the A/C corner. When this valve was closed, companies reported an immediate 50-psi increase in pressure. All water that was previously being lost through the damaged sprinkler systems could now be redirected to master stream devices.

Shutting down both control valves to the private fire loop did have a negative impact; it also shut off all water to the private yard hydrants on the warehouse’s B, C, and D sides. Units operating as part of the B exposure group didn’t need much water to extinguish the fires in the trailers as they broke out, so they had been using the yard hydrant system despite the limited water available.

When all water was shut off to these hydrants, the exposure group lost their positive water supply. Their only option for reestablishing positive water supply would have been long hoselays to the city water main grid on West Lugonia Avenue. Luckily, the only trailers to ignite were confined to a small area near the A/B corner.

(9) The fire building on arrival at the A/D corner; Bryn Mawr Avenue extends to the right of the photo. Four aerial master streams were eventually placed along the A side at left, but first-alarm units were still arriving at this time.

(10) At the A/D corner when the first-alarm units were still arriving, firefighters are standing where T211 would eventually operate an aerial master stream. Several trailers on the left side of the photo would eventually ignite, and companies assigned to the side B exposure group would operate to control these fires.

It was decided to use available tractors and drivers to move trailers forward five or 10 yards so there was some separation between the trailer and the dock door. Although this provided a pathway for directing a hose stream if needed, it put civilian truck drivers very close to the collapse zone.

Units operating at the back of the property on the B/C corner constantly faced water supply issues because of their remoteness from the city water grid. This issue appeared to be resolved when firefighters stretched a supply line to an adjacent property that featured its own private fire loop and associated fire pump. Success was short-lived, however, with the sector commander reporting a loss in pressure that they attributed to the fire pump on the adjacent property shutting down for unknown reasons.

Fire Lane

With such a rapid fire growth, it would be expected that the concrete wall assemblies would start failing during the fire’s early stages. In this case, it’s estimated they started failing 20 to 25 minutes into the incident. During the fire, it was noted that a number of the walls were bowing outward, but the majority of the walls collapsed inward into the warehouse. Fire codes have historically not specified how far away a fire lane must be from a building, which leads developers to place fire lanes very close to the building in certain instances to maximize every square foot of a property.

This was the case at 2255 West Lugonia Avenue. The fire lane on the warehouse’s C side was only six feet from the exterior concrete wall. As soon as collapse became an issue, access to the 615-foot C side was lost for the remainder of the incident, since most of the fire lane was located within the collapse zone. At one point, the D division commander considered maneuvering an apparatus down the fire lane to operate a deck gun through openings created by inward collapsed wall panels. While this would have provided better stream penetration, the risk associated with the move far outweighed the gains, especially on a building that was going to be a total loss.

Resources

For a major fire in metropolitan Los Angeles, you’d think unlimited mutual aid would be available for any incident. However, this fire was at the far eastern end of the San Gabriel Valley, bordered on the north and south by mountain ranges and to the east by the Mojave Desert.

Command immediately recognized the need for multiple truck companies to provide elevated master streams over the concrete tilt walls. However, as more truck companies were requested, the travel distance for these companies greatly increased. These truck companies came from the more populated areas west of Redlands. The sixth and seventh truck companies dispatched came from Rancho Cucamonga, more than 20 miles away.

In most large-scale incidents, units would be staging to relieve the initial alarm crews during the incident’s later stages. But in this incident, the three alarms plus special calls drained the county resources, particularly ladder trucks. All units in staging were put to work except for T175. It was not used early in the incident and was eventually released to provide truck coverage for the county. Thus, there were no relief companies for any of the units operating on the fireground.

Investigation

After the fire, the city of Redlands and the Office of the State Fire Marshal initiated an investigation to determine if the warehouse at 2255 West Lugonia Avenue was compliant with all fire codes applicable at the time of the fire. They also looked for any contributing factors to such rapid fire growth. As part of the investigation, the group gathered the basic facts concerning the warehouse’s construction details, which are included in this article.

The draft report of their findings found that all of the fire protection systems appeared to be working properly at the time of the fire. Contributing factors that led to rapid fire growth likely came from other factors.

Investigators discovered that at the time of the fire, all the smoke exhaust fans were turned on and the key for the switch had been broken off with the fans in exhaust mode. This created an estimated 399,000 cubic feet per minute air flow. The report points out that with all the fans operating, it created a 100% ventilation contribution, which is consistent with major large-loss fires in the past. The report also indicates the fans may also have been used for comfort relief.

In addition, the exhaust system intake louvers were at the ceiling level of the exterior walls, which was not in compliance with the fire code. The fire code called for the louvers to be mounted at the floor level.

The smoke exhaust system arrangement in this warehouse, particularly the fact that the fans were in full exhaust mode when the fire started, was extremely detrimental to the ESFR sprinkler system. The ESFR system depends on limited air movement at the ceiling level to provide the necessary spray pattern to achieve fast fire suppression of the fire. In this incident, the probability of failure was high.

Improper commodity storage can also play a role in large-loss fires. When high-piled storage plans were submitted to Redlands, the plans did not mention any exposed expanded and exposed unexpanded plastics. But the investigation team used owner-supplied surveillance video and data to determine that expanded and unexpanded plastics were present in the warehouse at the time of the fire. Furthermore, expanded plastics were noted to be stored higher than 25 feet. The 25-foot storage mark is important because storage beyond this height is beyond the scope of National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 13, Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems. So, the sprinkler system was not designed for all of the storage arrangements that were likely present at the time of the fire.

As a side note, the report also discovered an error in the fire protection system’s design. When the water demand for the automatic sprinkler system is determined, NFPA 13 requires adding a hose stream allowance to the sprinkler demand. For this warehouse, an allowance of 250 gpm was added. The report points out that a hose stream of 500 gpm was required based on the storage configuration present.

One of the questions the report brought up is the ultimate reliance placed on automatic sprinkler systems. If this system fails to perform appropriately, then the fire service is left with very few options to stop the fire’s progress. In the past, fire walls could help the fire service make a stand to limit the loss in a given fire situation. However, most codes have shifted toward allowing unlimited open areas for building construction when fire sprinkler systems are present, meaning firewalls are not required if sprinklers are present.

Along those lines, the layout of the private underground water mains can also severely hamper the fire service if the fire overtakes the sprinkler system. In this fire, the fire service had access to city water mains on the warehouse’s A side and part of the D side. However, the only water supply for the remainder of the building came from the private 10-inch fire loop.

As the fire overtook the sprinkler system and the ceiling collapse started to damage all of the sprinkler piping, it reduced the water pressure in the loop to almost zero because of water pouring out of this damaged piping. Trying to close all 16 post indicator valves to the sprinkler system was not attractive because it would be time consuming and place firefighters within or near the collapse zone. Thus, command had the dilemma of whether to close the two control valves from the city main to the private fire main. When command decided to close both control valves, it left large areas of the fireground without water supply. There may be instances in which positive water supply is desperately needed for exposure protection.

Occupant notification in a fire is another area that suffers from the reliance on automatic sprinkler systems. When an automatic sprinkler system is installed, the fire code allows a minimal occupant notification system because sprinkler systems are highly reliable. In the West Lugonia warehouse, only two horns/strobes were inside the 600,000-square-foot building. Occupants interviewed after the fire reported they did not hear a fire alarm and received very little warning of the need to evacuate. The occupants’ familiarity with the warehouse’s layout likely played a key role in preventing any loss of life. An estimated 100 employees were in the warehouse at the time of the fire.

Shortly after the fire, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and the Redlands Fire Department issued a press release announcing a $5,000 reward for the arrest of the individuals who started the fire at the West Lugonia warehouse. At present, the fire is officially still under investigation.

Lessons Learned and Reinforced

- Inspection. Fire departments must establish a method to inspect warehouse facilities featuring high-piled storage on a regular basis, including the proper use of nonrequired smoke exhaust fans. Think about prohibiting the installation of these fans, given the detrimental effect they can have on the sprinkler system.

- Dispatching. If the normal assignment for a commercial fire includes a truck company, the communications center should recognize that a commercial assignment was dispatched without one and correct it before dispatching the assignment or immediately thereafter.

- Unified communication. This fire showed the advantages of a unified communication system, since numerous departments from a wide area were involved. With CONFIRE, communications had a common dispatch channel, a common fireground channel, and a common tactical channel.

- 360° survey. Always complete the 360° survey on any fireground so that command can make the correct tactical decisions in regard to fireground strategy.

- Augmenting sprinklers. It is always wise to augment the automatic sprinkler system; this action may help overcome some unknown deficiency. Knowing the FDC’s location ahead of time and having this information in the prefire plan will enable you to do so in a timely manner.

- Occupant notification. This fire and similar ones raise the question about the absence of occupant notification systems in big box/warehouse occupancies.

- Private main control valves. Label all major control valves serving private fire mains. If there is more than one valve, label each connection as “1 of 2,” “2 of 2,” and so forth. The fire service must be able to quickly locate and close these valves when the fireground water supply situation dictates. Fire command must weigh the positive and negative aspects of closing these control valves when the water lost through broken sprinkler piping is taxing the available water supply. When designing a large-scale project such as this, consider a scenario in which the private fire main has to be abandoned. In the likely event the design process doesn’t adequately address a solution to this scenario, you must use preplanning to address the issue.

- Post indicator valve location. The valve serving each individual sprinkler system should not be located within the collapse zone.

- Fire lanes. You must consider fire lane design for large warehouses, specifically whether fire lanes should be situated within exterior wall collapse zones.

- Search and rescue. This fire showed that when excessive ventilation dramatically increases the spread of fire, search and rescue may not be an option. In this case, either the occupants made it out or they didn’t. By the time incident command could even think about a primary search, structural collapse was starting to occur and companies were being withdrawn from the building.

- Battalion chiefs. If battalion chiefs will not be available in a reasonable time to act as sector commanders, give company officers that task immediately to ensure that you maintain accountability throughout the incident.

- Safety officer. Even when units are operating defensively, it is imperative to establish a safety officer in a timely manner.

- Personnel accountability report (PAR). With a fireground as large as this coupled with a long-duration incident, consider conducting a PAR check, even though all units are operating defensively.

- Deploying civilians. Evaluate any action that would put civilians in harm’s way using the risk vs. gain method.

- Extra companies. Consider staging extra companies for personnel relief purposes and for safety in case something goes wrong.

- Ground master streams. Ground-based master stream devices were largely ineffective at this fire.

JEFFREY A. HARWELL is a fire protection engineer based in Burleson, Texas.