By Jim Silvernail

To go or not to go seems like a very simple concept. When a fire officer arrives at a fire he has to make a calculated decision on whether to enter harm’s way with his crew for an offensive interior attack or to safely take a defensive position and mitigate the situation from an exterior placement. Many times, the fire and the structure will present the circumstances that dictate our actions and guide the decision-making process. However, this isn’t always easy and often, our firegrounds are not even playing fields.

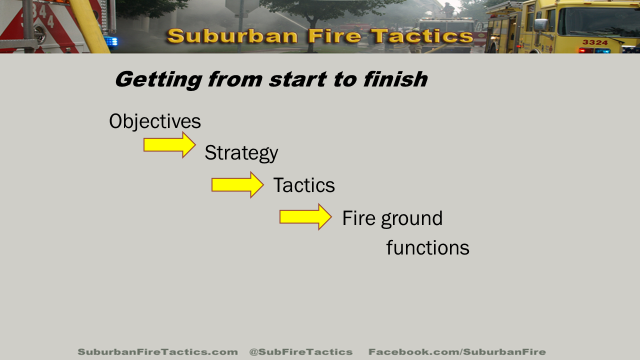

Fire Service Objectives

Fire service objectives are the same for every fire agency in the world. It is such an important concept that the entire first chapter of Suburban Fire Tactics was dedicated to summarizing this point. It is simple: We exist for three primary reasons:

1. To save life

2. To protect property

3. To reduce harmful impacts to the environment.

If we have the same objectives, why do agencies need to consider the specific circumstances that dictate their operations? Therefore, the theme remains “same objectives, different tactics.” How does this theme affect the “go” or “no go” (offensive, interior vs. defensive, exterior firefighting) decision-making process? To answer this question, we must analyze the Fire Service Risk-Based Management model.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Critical Decision Making: The Single Most Important Predictor of Success

A More Definite Risk Management Model

Size-Up and Risk Benefit for Small Commercial Structures

Commercial Building Fires: When To Go Defensive

Fire Service Risk-Based Management

We have all seen the fire service risk management principle:

Risk a lot to save a lot.

Risk a little to save a little.

Risk nothing to save nothing.

Simple, right? So what do you consider a lot? The answer is obvious: human life. A little can easily be equivalent to valuable property. But what is valuable property? Do we as firefighters get the opportunity to know what is valuable to another human being? Here is a better question, is your life (the firefighter’s life) more valuable than property?

The answer to the last question is absolutely. There is nothing more valuable than human life, especially a firefighter’s life. Every time I lecture, I pose this ultimate question: “Does your agency allow crews to enter unoccupied structures to save property?” Every once in a while, the answer is “No.” Do I turn my nose down at them and see them as negligent to their duties? No, I sometimes agree.

There is obviously a problem and trick with the question– the word “unoccupied.” A structure isn’t unoccupied until we, the fire service, determines it is unoccupied. But the other part of the problem is the assumed risk. Is risk the same for every agency? Aren’t all firegrounds considered immediately dangerous to life or health? Unfortunately, all fire service agencies are not created equal and do not possess the same resources, both physical and human, for fire suppression. Therefore, they have uneven playing fields and assume higher risks.

The Fireground Safety Net

Safe firefighting activities within a structure require certain fireground actions to be implemented on a consistent basis to guarantee crew safety. Often, some of these functions are taken for granted or are not used with consistency. Honestly, painful but real, certain agencies within this nation do not have the capability and resources to ensure this safety net at every fire. Fire officers need to be realistic when assessing fireground necessity and make a brave decision based on capability, not ego. As discussed in my book Suburban Fire Tactics, the variables of staffing, resources, and response area characteristics can have a serious effect on this reality and even handicap the safety net.

The elements of the fireground safety net include the following:

· Experienced fireground command officers who

o Understand and have the ability to safely, effectively, and efficiently implement standard operating procedures (SOPs).

o Understand building construction, building integrity.

o Possess the ability to have continual situational awareness.

o Have the ability to predict hostile fire events.

· Establishing a command structure, including a qualified safety officer.

· Placing an attack line in the proper place–the right size and at the proper time (almost always as soon as possible).

· Controlling the structure

o Ventilation/ventilation restriction.

o Utilities.

· Providing egress and softening the structure

o Making doors out of windows.

o Removing hazards such as bars and exterior door challenges.

o Placing ladders for above-grade egress.

· Communications and accountability

· Backup lines

o Protecting attack crews.

o Protecting stairwells.

o Protecting egress.

· Initial rapid intervention crew.

· Rapid intervention crew.

· EMS/Advanced cardiac life support.

Failure and Flirting with Disaster

Believe it or not, there are agencies in this country who cannot adequately establish the safety net on every structure fire consistently. The agencies that lack the resources and staffing often understand this predicament and take extra precautions to avoid the “gray zone” of “risk a little.” They understand their limitations and develop policies to make quick assessments to determine life hazard. Once the life hazard has been removed, they immediately move to a defensive operation. Many may argue that they are violating the objectives of the fire service. However, I would agree that they are complying with the risk based model because of their inability to manage and alleviate risk taking. Playing fields, unfortunately, are not created equal, and resources aren’t always equitable.

Flirting with disaster occurs for numerous reasons. One favorite example is “I have a rapid intervention team or rapid intervention crew; therefore I am compliant and safe.” Remember, the RIT/RIC is only one component of the fireground safety net. It is not the golden parachute that provides overall safety. Often the question is asked: “Do you have a RIT/RIC at every fire?” The answer is almost always yes, regardless of reality. The second question is: “Do you always have an advanced life support ambulance ready at every fireground?” Approximately half the hands stay up. What causes more fireground fatalities, cardiac events or collapses/trapped firefighters? The answer is obvious. Both functions are equally as important but just pieces of the safety puzzle.

Among the reasons for disaster are the following:

· Fireground inconsistency

· Incomplete fireground functions

· Overestimating capabilities and resources

· Poor fireground leadership/accountability

· Poor fireground discipline

· HUBRIS

· Misinterpreting the Fire Service Risk-Based Fireground model

The “Gray” Area: Risk A little

We understand what “risk a lot to save a lot” and “risk nothing to save nothing” mean. The only variable is the ability to truly understand when there is a life at stake and when there is zero possibility of tenability. Once this has been established, the decision should be less challenging than the “gray” area.

Being able to make decisions within the “gray” area depends on your ability to manage risk and to truly understand your capabilities to establish the complete fireground safety net. This decision making often requires the following:

· Experienced company officers

· Effective training programs

· Effective standard operating guidelines.

Remember your objectives; remember the Fire Service Risk-Based Management model; establish a complete fireground safety net; and always keep it safe, effective, and efficient.

BIO

Jim Silvernail is a battalion chief with the Metro West Fire Protection District of St. Louis County, Missouri. He has more than 17 years of experience and is a lead instructor at the St. Louis County Fire Academy. He is also a member of MO-TF1 (FEMA Urban Search & Rescue). He is the author of Suburban Fire Tactics (Fire Engineering Books and Videos, 2013) and has been published numerous times in Fire Engineering magazine. He is a workshop instructor at FDIC International and presents at various regional conferences. He is a member of the International Society of Fire Service Instructors and is principal member of the National Fire Protection Association 1710 Technical Committee.