Working fires are stressful and dangerous operations. In most instances, we are called to an unfamiliar house and have no knowledge of the layout of the living spaces, the condition of the structure, or the location of the inherent hazards. Every building has its own specifications and challenges. The fire service does conduct training on types of building construction and, after some time on the job, most have had hands-on experience and opportunities to learn about common traits and characteristics of each type of construction.

Although many aspects of construction vary from house to house, some key common elements can guide firefighters as to the possible layout of a building. These are not all-inclusive, and any homeowner can change internal arrangements, but having an idea of what to look for can still give you a good head start.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Building Construction: Understanding Structural Loads and Loading

Reading A Building – Practicing The Theory

Occupancy Classifications: An Orientation

The setting is a residential subdivision with standard lightweight wood-frame one- and two-story structures. Using one of these residences, let’s look at some tips that can help you gather important information during your 360° of the fire scene.

A Side

The A side is normally the side facing the street or with the main entrance to the residence. Looking at the front of the house, you can note some characteristics (photo 1). This is a two-story single-family residence with an attached garage. It is a lightweight wood-frame-style house, so knowing where the fire is and how long it has been burning are critical. The design of these style homes has the bedrooms upstairs and the gathering rooms downstairs. Surrounding the door are four equally shaped and sized windows.

(1) Photos by author.

The most common rooms off a front door are living rooms, dens, and dining rooms. Considering the fireplace is on the D side, you can determine the living room is in the A/D corner and the dining room/den is to the left of the door. The windows on the second floor are equivalent to the ones below. Between the two windows on the second floor is a small decorative window. The roof line has three distinct levels: (1) above the garage, (2) the central portion of the house, and (3) above the D side of the house. These building traits would indicate the master bedroom is above the living room and another bedroom is above the dining room.

Notice there are no vent pipes above these windows, signifying no plumbing. The small window is most likely a closet. The garage is on the A/B corner of the house with its own roofline. A privacy fence surrounding the property can be a small challenge for first-arriving units, so noting where and how wide the entry gate is are important.

B Side

The B side of the house has some important design points (photo 2). The first is the side door. This obviously enters the garage and is a faster entry option than the front garage door. If the fire is in the garage, you can manage the flow path more efficiently and control the suppression efforts.

(2)

The second point to remember is to look up. Looking near the peak of the roof, there is one double-pane window in the center of the wall. Given the size of the house, the height of the roofline, and the fact this side has a different roof level, it is easy to determine there is a room over the garage. Commonly known by the acronym FROG (furnished room over garage), these areas are commonly used as additional bedrooms, offices, and playrooms. From the outside, it gives the appearance that it is a large room spanning the side of the house. Sometimes this can be the case, but many times these rooms have large void spaces that can allow fire to hide and move quickly throughout the house.

The third point to note is the electrical meter (photo 3). You can see there is no overhead mast and the conduit comes up from the bottom. The house is fed from underground power lines going into the meter box. This is important for several reasons. Not only does it give you the entire B side of the house for egress ladders, but it also lets crews know that to secure the power the panel box is in close proximity to this meter inside the building. Looking at the layout, it is safe to assume the service panel is in the garage along the B wall.

Note the lack of windows at grade level. Finding the same situation on sides C and D likely indicates the absence of a basement, a particularly important issue in lightweight construction. Many homes across America of lightweight construction have exposed lightweight wood beams in the basement, a dan-gerous condition identified through both research and actual experience.

(3)

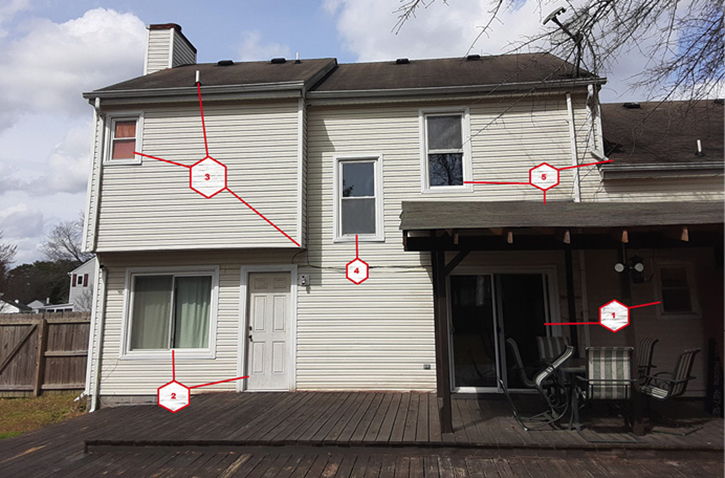

C Side

The C side of the house is normally the rear of the building. You can learn a lot in a hurry. You can identify any major hazards to firefighters (pools, greenhouses, and so on) and see how much room there is for a working area. You also can look at the house and check for additional routes of entry/egress for access or rescue operations. Close any open doors to isolate or reduce any flow path concerns.

Now, focus on the house itself. Looking at the building, you can pick out other key points to aid crews. The size and location of windows and doors can give you clues as to the rooms behind them. The roof and the walls have features to look for that help develop the picture. In photo 4, you can see a small window to the right of the sliding door. This type of window is commonly above the kitchen sink. Given its location, you can determine that you can access the kitchen through the sliding door, and it goes to the right toward the garage. Looking at the C/D corner, the window is accompanied by a door. Remembering what you saw in the front of the building with the chimney and roofline, you can confirm this is the living room.

(4)

The second floor has several distinct characteristics. The C/D corner shows a small window, a vent pipe on the roof, and the entire section extended from the rest of the building. Added to the roofline change, these factors can help you conclude that this is the master bathroom. The single window in the center of the wall seems out of place. This is a common placement for a window if the house has a split direction stairwell with a center landing. There is a porch roof below another window that extends past the dropped roofline. This appears to be another bedroom, and the porch roof gives crews fast access to the bedroom and the roof. The C side of this house gives operating crews many tactical advantages for suppression, search, and rescue.

D Side

The D side completes the view (photo 5). The small window in the corner matches up to the small window on the C side, confirming this is the master bathroom. It also appears there is a gate opening on both sides, which is another note for fire crews. The presence of a large propane cylinder next to the fireplace indicates an ancillary heat source, most likely a wall-mounted gas heater or a gas log fireplace insert. Regardless of the appliance, knowing about this hazard is a critical factor when putting together your action plan, as you will need to remove this as an incident hazard.

(5)

The chimney is built outside of the structure. There is no cleanout at the bottom, and it is encased in vinyl, so it is safe to determine this is not a concrete block chimney. This is another hidden travel area for fire spread. A faulty flue can cause vertical fire spread to the second floor or the attic. Chimney fires like this have caused serious injuries to firefighters. In October 2000, a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) report described the rapid spread of a fire in a chimney that extended to all floors and sent three firefighters to the hospital. (See NIOSH F2000-43.)

Hidden Hazards

Identifying distinguishing traits and characteristics of a house can be more than just what you can see from the outside. In fact, it is those exterior visual cues that should trigger you to consider the potential for the traits that you cannot see. Knowing what we do about lightweight wood-frame construction and how contractors look to conserve space for increased profit, there are several areas that firefighters need to remember and report on during a working fire operation. Attic areas and void spaces pose serious hazards to interior operations. A few tactical considerations can serve as a refresher for our senior crews and maybe a few new tools for the junior members on the company.

Attack Considerations

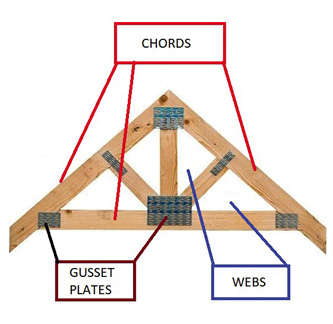

Lightweight construction is not designed to withstand fire impingement for long periods of time. Earlier wood-frame houses have roof components that are built on site with main beams and rafters; newer houses are different. To save time and money, roofs are now commonly built with components known as truss systems, which are built off site and mass manufactured. A truss is a collective of small members called webs that connect a bottom and top chord by using thin strips of metal known as gusset plates (photo 6). These plates are pressed into the wood, held by thin spikes no longer than 1⁄16 inch (photo 7). When temperatures climb, these systems fail quickly.

(6)

(7)

This home has characteristics of older and newer construction. Although it is obvious that this home is made of lightweight construction, the roof is uncommonly different. Notice the absence of web members and gusset plates. You can see that there are 2 × 6 timbers and a ridge board (or pole), which are indicative of rafters. In addition to the construction, overhead obstructions can cause serious problems.

Heating and ventilation systems have developed over the years to more efficiently heat and cool, reducing size and saving space in the common areas. Many times, the air-handling units and the ductwork are in the attic. These systems can add hundreds or even thousands of pounds and with a heavy fire load can be a collapse hazard. Additionally, these units have ductwork distributed across the attic, which can cause firefighter entanglement (photo 8).

(8)

The attic space is many times unfinished, which creates walking hazards for firefighters, and although the roof levels may differ from the exterior, there normally are no firewalls to separate the parts of a single-family home. The attic area is normally accessible the entire length of the house, which causes flow path and fire flow concerns.

Changes in the roofline or space height in an attic area indicate a different section of the building. With an attached garage, the pitch of the garage roof could be different, and the roof could be longer. Those changes would be seen in the attic with changes in the framing. Transitioning to the attic over the garage, you may have an open area to enter, but it could be small, and it may be easier to access this area through another room (photo 9).

(9)

Void Spaces

One of the biggest hidden hazards on the interior is void spaces—areas of the structure that have been sealed off or barricaded and are considered uninhabitable. They are part of the original framing footprint of the structure, and after interior rooms are framed in and finished, there are portions of the building not used. Void spaces are unfinished and contain components of the building mechanical systems. Sometimes, void spaces are used for storage, which can add another layer of danger in a fire. In dark, smoke-filled atmospheres, access to these areas may be overlooked, which can cause portions of the house to go unchecked.

Void spaces are commonly found on both sides of the FROG, with knee walls separating them from the finished areas (photo 10). These knee walls can have access doors for occupants to use the space for storage and to access mechanical components of the operating systems. Sometimes, the doors are not readily obvious. People have them built in closets or hidden behind beds.

(10)

At first glance, these areas may not appear to be very large, but most of them run the entire length of the prefinished space. This makes for a large, open area that connects several adjoining rooms. Void spaces like this create a direct route for the fire to travel and grow in intensity (photo 11). All the unprotected framework can be rapidly compromised.

(11)

Void spaces often connect more than a couple of rooms. The design of a house can cause hidden spaces to connect to each other, directly or indirectly. Void spaces on opposite sides of the house can open up to the common attic space, which connects all of the areas. This hidden network is an open flow path for rapid fire spread and structure deterioration (photo 12). Visualizing the layout ahead of time alerts firefighters to the presence of possible void space hazards.

(12)

Hidden spaces are everywhere in a house. Many are not given much consideration during fire conditions, but if a fire occurs in the area of the house near these spots, crews need to open them up and check inside. Sometimes homeowners take advantage of these areas in ways not commonly seen. A split direction stairway with a landing creates a large open area that is closed in. This space has been used for storage and, in some instances, a pet sleeping area. Any openings give the fire a faster opportunity to spread (photos 13, 14).

(13)

(14)

Strategy and Tactics

For a working fire in this house, it is crucial to initiate an incident action plan quickly. The fastest way to mitigate the hazards is to find the seat of the fire and get it under control. Incident commanders (ICs) must consider all seven sides of the fire: the interior, the top (ceilings, attics, and floors above), the bottom (fire on the floor below, including any crawl spaces and basements), and all four sides (any areas alongside the fire—rooms, buildings, and so on). Included in these seven sides are all possible concealed spaces of all those sides (walls, attics, void spaces, renovations, and so on).

Identifying where the void spaces are is important, but so is identifying if the void space has a floor. Locate the landmarks to the void space by moving to where the slope of the roof meets with the exterior walls; that puts you below the space behind the knee walls. If there was a floor that extended behind the knee walls, firefighters attempting to pull ceiling from below would encounter a floor and would have great difficulty opening the space from below. If there are no floors, pulling ceilings below the space gives you fast access behind the knee walls. If there is active fire in that space, this gives crews a great tactical advantage from a safer location.

Identification, inspection, and action in the concealed space fires can save the building. ICs who consider not damaging these areas and investigating will more than likely have to adjust their strategy when the fire gets ahead of them. To confirm the fire is out, crews need to inspect every area that the fire can possibly travel. A fire in the living room of this house can easily travel to the eaves over the garage very quickly. Traveling through the void spaces and across the open flow path of the attic, a crew could call a fire under control downstairs and not see black smoke and fire coming from the eaves in the B/C corner.

Be aggressive and be thorough. Open the walls and ceilings until you find unburned components. Get into the attic spaces—ALL of them. This may require crews to make access in several areas throughout the house. If the house has a built-in chimney (boxed in and framed), inspect the chimney box by pulling some siding and making an inspection hole. Check for access behind knee walls. If there is no access, open up and inspect the void spaces. If you aren’t sure if there is a void space, OPEN it up. It’s better to make the hole and be wrong than to dismiss the area and overlook a pocket of fire. A thermal imaging camera is a great option for scanning areas of the house to find pockets of heat that may have traveled from the seat of the fire.

Exercise the Tools

Get out in the run area and look at what you have around you. Knock on some doors and introduce yourselves to the families and ask if you can walk around the house. Have everyone at the station do a walk-around of their houses and take pictures. On the next duty day, everyone in the crew can exchange with someone else. Do a 360 with the photos and see what you identify. On your incident responses, don’t just walk around the building. Use the clues the structure gives you, enhance your ability to understand the building layout, and sharpen the tools for your operations toolbox.

Duane Daggers is a 35-year veteran of the fire service and the battalion chief of health and safety with the Chesapeake (VA) Fire Department. He is a life member with the Gouldsboro (PA) Volunteer Fire Company, has been an active instructor for more than 20 years, and is a nationally registered paramedic. He has a master’s degree in occupational safety and health, a bachelor’s degree in organizational leadership and management, and associate degrees in fire science and emergency management.