BY JEFF PAULEY

Public agency fire investigators can be either full-time investigators or inspector/investigators, while others are assigned to an operational company and investigation is an additional responsibility. Regardless of the assignment, they have an important fire service role, but they must be aware of the latest postfire scene research and incorporate health and safety best practices into their work.

- Firefighter Cancer Prevention: Using the Tools Provided to Us

- Fire Investigation Basics

- A STRUCTURED SYSTEM FOR FIRE INVESTIGATOR SAFETY

Until recently, we have had to extrapolate fire scene research to the postfire environment, but that is changing. Recent research focused on the postfire environment is producing results, and more research projects are developing as it becomes more apparent that we are an underserved population within the fire service. Fire investigators have high exposure rates to harmful chemicals and particulates; most are at more fire scenes than the average firefighter for longer and unfortunately are often less well protected from the hazards present.

There are about 1.1 million career and volunteer firefighters in the United States. The staff of the forthcoming National Firefighter Registry that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is developing has estimated that the average firefighter spends about five percent of his time in the fire environment.1 Based on a career firefighter shift schedule of 2,912 work hours per year, the average firefighter’s direct exposure to active fire scenes is about 146 hours annually.

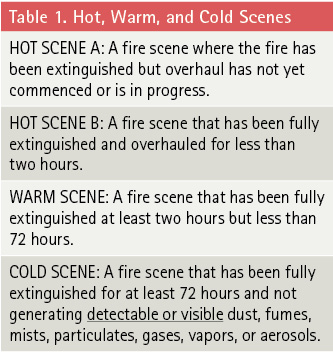

Source: Table by author; from Fire Investigator Health and Safety Best Practices, Third Edition, IAAI, April 2022.

Currently, there are about 10,000 public and private fire investigators in the United States, members of either the International Association of Arson Investigators (IAAI) or the National Association of Fire Investigators or both. On average, a fire scene examination takes about three hours, based on data from the University of Miami’s wristband research discussed below. Think about how many fires you investigate in a year and how long you are in the postfire environment at each one. My guess is that many of you exceed 116 hours.

Scene Categories and Zones

Consider some basic concepts regarding the postfire scene. To understand and define these scenes better, I have divided them into time- and distance-based categories that apply to every postfire scene. They were first described in the inaugural edition of the IAAI’s Health & Safety Committee’s Fire Investigator Health and Safety Best Practices in 2018 and have since been referenced in several research papers.

To help fire investigators understand the personal protective equipment (PPE) precautions that they should take at the various postfire scenes, we developed a hazardous materials-style, time-based scene classification system to indicate the four fire scene time periods from an investigative perspective (Table 1).

We used these categories to identify and determine the most appropriate PPE that fire investigators should wear based on each scene’s specific conditions. Note that, regardless of the time since extinguishment, if the cold scene is still generating visible substances, it becomes a warm scene.

On the other hand, fire scene zones are geographic, or distance based. Every postfire scene has these, regardless of how long the fire has been extinguished (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Hot, Warm, and Cold Zones

Source: Figure by author, from Fire Investigator Health and Safety Best Practices, Third Edition, IAAI, April 2022.

The hot zone includes whatever has burned and its associated debris field and collapse zone. In most instances, you should limit access to this area to investigators only. However, if this is or has the potential to become a crime scene, you should monitor the entry and keep a log of every person entering and leaving the zone. You also may need to delineate this area with red warning tape.

The warm zone is defined by the smoke plume’s intensity and direction of travel. It includes an area immediately outside the hot zone of sufficient size and shape to limit exposure to contaminants and the decontamination area at its outer edge. Always wear respiratory protection in this area until gross decontamination is completed and move immediately to the cold zone. You may also need to delineate this area with yellow warning tape.

In the warm zone, understand that when fire smoke cools, its particulate matter returns to the ground. This particulate matter around the fire scene can be harmful when stirred up and then inhaled or absorbed, hence the need for PPE, including respiratory protection, in this area, called the “sootprint.” You should not underestimate its size since the human eye cannot see the nanoparticulate matter that makes up smoke. Therefore, you must consider the smoke plume when defining the warm zone. Although rain or snow can mitigate these hazards to some extent, this is typically the exception at most fire scenes.

The postfire scene cold zone includes all scene areas outside the warm zone. It’s immediately outside the established warm zone, where personnel are relatively safe from the adverse effects of a fire, toxic chemicals, carcinogens, and so forth. The cold zone typically contains the command post and other support functions necessary to control and manage the incident.

Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment

Some fire investigators may not be at the fire scene as a part of a working operations crew but arrive while suppression activities are still in progress or just wrapping up. If you arrive later in the incident, you should be enrolled in the personnel accountability system. After parking upwind when possible and donning your PPE, you must first check in with the incident commander (IC). This is also the opportunity to start to gather safety-related information regarding the hazards and problems that may be present. You should ask at least three critical questions: whether foam was used and, if so, what type; how much water has been flowed into the structure or scene; and whether any ventilation holes were cut anywhere. You should also interview the first-in crew to see if they observed any hazards that could affect the investigation.

Just as the first-arriving fire officer should conduct a 360º walk-around of the entire structure or scene, the fire investigator should do the same, once the scene is stable and with the permission of the IC. This exterior hazard assessment will give you, the investigator, a feel for what it is you are dealing with. Unfortunately, at this point many fire investigators are not wearing the PPE they should. Again, keep in mind the sootprint issue discussed above.

A study by Dr. Alberto Caban-Martinez, et al., of the University of Miami2 has shown that the air in the warm zone of a fire scene contains many harmful toxicants, which means that those in this area need to wear adequate PPE, including respiratory protection. What is sufficient depends on the situation but, at a minimum, it should include covering as much skin as possible and effective respiratory protection.3 This hazard is present in the postfire scene as well.

Interior Assessment

Next is the interior assessment, where the search for known and anticipated or potential hazards continues. Again, you need to be cautious because of the very nature of postfire scenes—that debris (itself a hazard) and poor lighting hide hazards.

The next step in the process is to conduct a risk assessment of the identified actual and potential hazards. No scene will be hazard-free. Whether done informally by one or a small group of fire investigators at a scene or as part of a formal process at a more extensive investigation, conducting a risk assessment and analysis is a critical step you should take at the beginning of every scene exam and, if necessary, every day after that. You should do it any time during the investigation and whenever conditions change.

The risk assessment and analysis process involves looking at each identified actual and potential hazard and making a judgment regarding the likelihood of something bad happening and, if it did, the acute consequences. Once you have identified all the actual and potential hazards, the next step is to determine the level of risk and the likelihood of occurrence associated with each. This will help you determine how likely each hazard is to occur and how much damage or injury would result and aid you in understanding the relationship between the cause of the hazard and any subsequent effect. You should document this exercise in the investigation report.

Postfire Scene Health Hazards

While these exterior and interior hazard assessments should identify the actual and potential safety issues at the scene, they do not address the health hazards. One thing every fire investigator must understand is that virtually every postfire scene contains health hazards, regardless of how long the fire has been extinguished. For example, Underwriters Laboratories Fire Safety Research Institute (UL FSRI) research conducted in 20204 regarding the postfire environment recorded significant levels of particulates and some hazardous airborne chemicals as far as five days out (the study limit).

- Particulate levels ranged from moderate to extremely hazardous Air Quality Index levels in most scenes five days out.

- Most gas levels were down after two hours; however, formaldehyde levels increased over time in some cases and exceeded the UL FSRI NIOSH ceiling limit.

“The most important findings of the UL FSRI study are that (1) elevated and hazardous levels of airborne particulate may be encountered during all phases of the post-fire investigation depending on the activities of the fire investigator, and (2) airborne formaldehyde concentrations could exceed recommended exposure limits in extended phases of the post-fire investigation.”4

To take this a step further, the University of Miami’s Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center has looked at the chemicals in the postfire environment for several years. Using silicone wristbands worn during postfire scene examinations that absorb chemicals at the scene, researchers measured the levels of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the ambient air. These are classified as priority pollutants by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency because of their adverse effects on human health, persistence in environmental matrices, and reactivity and ability to transform into more active species. In an unpublished report5 on a subset of this research project, 13 public and private fire investigators in North Carolina submitted 35 bands. The average scene examination lasted about three hours. Half of these exams were conducted on the day of the fire. The others occurred several days to several weeks after. In every instance, there were significantly high naphthalene and phenanthrene readings and relatively high readings of other PAHs in many cases.

These two studies, the first in-depth looks at the health hazards of the postfire environment, clearly show that the health hazards persist for an extended period after a fire is extinguished and that PPE, including respiratory protection, is needed at virtually every postfire scene.

As suspected from other research and confirmed in the UL study noted above, particulate matter called nanoparticulates, which are not visible to the human eye, persist in the postfire environment for at least five days and more than likely until the scene is cleaned or destroyed. They are also stirred up whenever the air is disturbed; the smaller the particle, the longer it remains suspended in the air. When inhaled, these nanoparticulates go deep into your lungs and cause serious health issues.

Additional research is planned regarding the persistence of nanoparticulate matter in the postfire environment and how far it can extend out from the hot zone. Still, it is present in the hot and warm zones, and ventilation does not effectively dissipate it. No postfire scene is safe from these health hazards, regardless of how long the fire has been extinguished.

It is true that today’s structure fire is not like those of yesteryear. The harmful gases produced as a combustion by-product from the many manmade items in today’s structures make these scenes much more hazardous in this regard than before. Now there is science to confirm it. Nanoparticulates have always been present, but now we know more about their harmful composition and that molecules of these toxic gases can also be attached to them.

The gases and particulates in almost every postfire scene can cause cancer and other health issues for fire investigators if you do not take proper precautions. The best way to help ensure that working in these scenes does not lead to health issues is to always wear appropriate and effective PPE, including respiratory protection, whenever you are in the warm or hot zone of every postfire scene.

This article just scratches the surface of this important subject. To help you better understand the health and safety complexities of this work environment, the IAAI Health & Safety Committee recently published the third edition of its Fire Investigator Health and Safety Best Practices. This important document is available to everyone, regardless of IAAI membership, at www.iaaiwhitepaper.com. This should be required reading for every fire investigator.

As we become more aware of the health hazards associated with the postfire environment and their association with occupational health and cancer, it becomes more important for fire investigators to protect themselves to the greatest extent possible.

Endnotes

1. Presentation by Kenny Fent, Ph.D. to the National Firefighter Cancer Symposium, February 25, 2022, Miami, Florida.

2. A. J. Caban-Martinez et al, The “Warm Zone” Cases: Environmental Monitoring Immediately Outside the Fire Incident Response Arena by Firefighters, Safety and Health at Work, Volume 9, Issue 3, September 2018, 352-355.

3. The IAAI-recommended minimum respirator assembly for all U.S. fire investigators while in the hot and warm zone of every warm and cold fire scene is a half-mask facepiece with goggles, or a full facepiece, that has a P100 particulate filter with an OV/AG/FM gas/vapor. In a hot A or B scene, fire investigators should wear self-contained breathing apparatus. Source: Fire Investigator Health and Safety Best Practices, 3rd edition, April 2022, IAAI.

4. G Horn, D Madryzkowski, DL Neumann, AC Mayer, and KW Fent, “Airborne contamination during post-fire investigations: hot, warm and cold scenes,” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 2022 Jan;19(1):35-49.

5. The researchers are writing this paper and hope to have it peer reviewed and published later this year.

JEFF PAULEY is the chairman of the International Association of Arson Investigators Health and Safety Committee. A former Virginia fire marshal and private fire investigator, he is an adjunct instructor with the Virginia Fire Marshal Academy. He has a master’s degree in occupational safety and health from Columbia Southern University.