BY ANTHONY AVILLO

I am a major proponent of experience as a great teacher and a believer in the theory of recognition-primed decision making (RPD) as a quintessential factor in the genesis of strategy. In a nutshell, from the perspective of a fireground commander, RPD represents a method by which decisions are made based on previous situations and the decisions that were made at that time. This memory and experience-based knowledge and action drive our initial decisions and are compared with the current situation. From there, based on that situation, adjustments can be made, creating new situations to be stored in the brain for later use at another incident, which may or may not be similar. The use of RPD functions well in conditions fraught with the pressure of time in which information is incomplete and the situation is not completely defined. Hmm … sounds a lot like the fireground on arrival.

Although RPD is applied to both the experienced and the inexperienced and how they manage their decision-making processes, those with more experience obviously have more potential courses of action in their brain-bank that have been used previously, whether successful or not. Because of this, experienced individuals will generally be able to come up with quicker decisions because the situation may match a situation they have encountered before. The split-second rundown of the mental file cabinet enables appropriate (hopefully) decisions to be made. Thus, experienced decision makers are more likely to correctly assess the situation and develop a viable course of action more quickly because their expert knowledge can rapidly be used to disqualify incorrect courses of action. With this in mind, consider the following déjà-vu type fire.

SCENARIO

It is 0529 hours on a really cold morning on the last day of 2012. As regional tour commander of the First Platoon in North Hudson (NJ) Regional Fire and Rescue, I am on a response to a reported smoke condition at 7429 3rd Avenue in North Bergen. This is in the third battalion. North Hudson Regional protects five extremely densely populated cities in northern New Jersey, directly across the Hudson River from the borough of Manhattan, New York City. We never have a fire without an exposure concern. Along with North Bergen, we also serve the municipalities of Guttenberg, Weehawken, West New York, and Union City, spread across three battalions. Our apparatus complement is 10 engine companies, four ladder companies, a heavy rescue company, a safety officer who responds with our accountability officer (the command technician), the aforementioned three battalion chiefs, and me as the platoon commander. We respond with a staffing of three personnel 99 percent of the time; this day was no different. My quarters are in Union City on 29th Street, so my response of 45 blocks and then a cross-street traverse to the address on 3rd Avenue was going to take a bit of time.

While en route, I was notified that Battalion (B) 3’s car was not starting and he would be delayed. That also delayed Engine (E) 9, who is behind B-3 in the single-bay, turn-of-the-century firehouse. This brought a modification to the response: E-5 and B-2 were dispatched to 3rd Avenue from their quarters on 43rd Street, Union City.

A minute or so later, at 0532 hours, another set of three tones came across the air for a reported fire at 15 Riverview Court in Weehawken. I had never heard of that address, and I was not assigned to that alarm at the time. I asked for clarification and was told that the address was now 8000 River Road, the Roc Harbor complex in North Bergen. This is also in the third battalion but on the extreme northeast end on our waterfront. The third battalion companies were already responding to 3rd Avenue, which is on the top of the cliffs, where most of the North Hudson population is, farther west from the river.

As a result, the companies on the response to Roc Harbor were the companies in the first and second battalions, which are in a more southern portion of the region, some distance away. The region runs about five miles north to south and three miles east to west from the Hudson River to the New Jersey Meadowlands on the west. The normal response to Roc Harbor was E-9; Squad (Sq) 10; E-13; Sq-1, 7 (rapid intervention crew); L-4, 5; Rescue (R) 1; B-3; Safety 1; and Deputy 1. Because all of those third battalion companies were up on top of the hill on 3rd Avenue, with E-5 and B-2 also on their way there, the companies responding to Roc Harbor were E-1; Sq-2; E-3, 4; L-1, 3; and B-1. It was easily a 10-minute-plus response.

I was still on my way to 3rd Avenue and notified my dispatch center that I would continue toward that alarm until I had the first on-scene report before deciding whether to respond to Roc Harbor. The first report from 3rd Avenue was that nothing was showing, so I redirected down to 8000 River Road, where I was the first to arrive.

Round 1: March 6, 2000

Flashback to March 6, 2000. The time is 1210 hours. I am arriving on scene as the acting deputy chief (I was a battalion chief then, acting as platoon commander for the day) and was confronted with a large body of fire in a three-story, lightweight, wood-frame condo unit attached to similar units on both sides. There is a detailed case study of this fire in the “Contiguous Structures” chapter in the Fireground Strategies1 textbook, so I will just give a brief synopsis of that fire here (photos 1-3).

|

| (1) This is in 2000. You can see the smoke is going toward the D exposure. Note the fire has broken through the roof. Also notice that no master streams are pushing the fire back into the building. The water tower is knocking down the combustible wall and roof fire. Although it doesn’t look it, things are getting better. (Photo by Robert Scollan.) |

|

| (2) This is a shot of the fire unit looking from the D exposure. All the floors pancaked right down into the garage. Note where the trusses were ripped out of the floor void because of the impact load of the collapsing floors. (Photo by author.) |

|

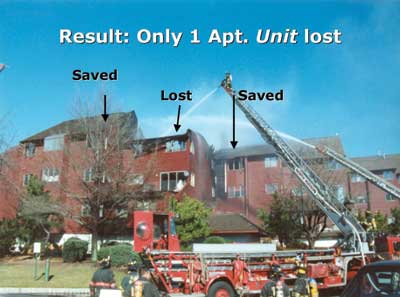

| (3) The result: Only one unit was lost. The pincer action strategy employed an interior defensive operation in each adjacent exposure. It worked. (Photo by Robert Scollan.) |

The fire started on a lower floor and autoexposed up the rough wooden combustible siding and entered the top floor and attic space where the lightweight wood trusses are. Because of the fire in the void and the anticipation of a collapse, a defensive operation was pursued in the fire unit and an interior defensive operation in both exposures. Interior defensive operations include a search of the exposure, placing protective hoselines in any directly exposed areas immediately connected to the fire building, and conducting precontrol overhaul to expose any potential avenues of fire spread, all done under the supervision of a division commander assigned to that exposure.

The fire unit eventually collapsed right down into the garage, pancaking all the lower floors with it, but the exposures were held and undamaged for several reasons. The first is that we requested additional help early. This fire went to five alarms, and we needed every person who responded. Second, some great reports from around the fireground, courtesy of the assigned division commanders, assisted Command in decision making and reinforcement of affected areas. Third, a whole lot of real hard-nosed firefighting took place to hold the exposures in check. Fourth, and maybe most importantly, the combustible roof burned off (we had made some initial holes from an aerial but abandoned the operation as the fire took hold of the unit). When the roof started burning through, the fire was no longer as much of a lateral threat as it had been, and conditions began to get better. Note: We did not use aerial master streams into the roof hole until most of the roof had burned away. The fire was going up and out; we did not want to push it back in.

The result of this fire was that only one unit was lost. All of this was going through my mind as I was responding to the same complex almost 13 years later. I was thinking about what had worked and what had not. I was also thinking about the difficulties in establishing water supplies in a limited-access complex with even more limited access to the units themselves. This complex, which was built in 1980, is horseshoe-shaped and has two access roads on the perimeter of the structures. This access road runs from River Road and splits and runs behind the units on the north and south sides, ending at the Hudson River. There is a park-like area in the middle of the complex, where the entrances to the units are located. For our purposes, I will refer to this area as “inside the horseshoe.”

To get there, we had to stretch a huge amount of hose. One way was through the garage of an uninvolved unit, up a few steps to grade, and into the center area (inside the horseshoe), where the units were accessed by exterior wood stairways. The only other access was at the head (west end) of the property, where there was a small access path that led to the inside of the horseshoe. It is not big enough to fit an apparatus. What made matters worse is that the entire complex was under several feet of water during Hurricane Sandy, causing a great deal of damage to the pathways leading into and winding through the area. This inside-the-horseshoe area was a problem in 2000. It would be a problem today. Back in 2000, I believe we secured four separate water supplies. At this fire, we would use five. Being at the bottom of the Palisade Cliffs and coupled with the 24-inch mains on River Road, the road leading to the complex, water volume was not a problem.

The lessons I learned back in 2000 would serve me well throughout my career and certainly on this last day of 2012. In fact, personnel, organization, communication, and hard-nosed firefighting that were the keys to success more than a decade ago constituted the same formula for success here. We would need all that and more to control this one. As we will see, the alarm up on 3rd Avenue notwithstanding, Chief Murphy and his law would rear its head many times at this fire.

Round 2: December 31, 2012, 0532 hours: Initial Operations

Back to 2012. As I was responding, I knew that the companies coming from the southern part of the region would take longer (it seemed like forever), and I would likely be on the scene by myself for a time. This, in fact, is what happened. I pulled up to a building about four units to the east from the rebuilt structure that burned in 2000 and was greeted by a heavy smoke condition on all three floors with fire beginning to break through the wall on the D side between the first and second floors. Remembering that this building not only had a peaked truss roof but also parallel-chord wood truss floors, I was aware of the likelihood of fire in the voids on arrival.

I was met by tenants who told me that they awoke to find heavy smoke pushing out from the utility rooms where the heating units were on two separate floors. They were stacked right along the D wall, where the fire was breaking through. They told me that no one was inside (photo 4).

|

| (4) This is a photo of early conditions. We have gone defensive. The Bravo exposure is at the extreme left, and the Delta exposure is partially obscured by smoke. This view shows where the command post is set up, at the rear of the buildings. (Photo by Ron Jeffers.) |

I gave my preliminary size-up report and struck a second alarm. At this time, 3rd Avenue Command had reduced the assignment on the top of the hill but was still holding three engines and a ladder company. My on-scene time was 10 minutes. In fact, the first-arriving unit was L-3, which came from on top of the hill at 46th Street in Weehawken, a long haul for a first-arriving ladder. It got to the scene in 14 minutes. For us, that is a really long time. Our first companies are usually on scene in three to five minutes, so this response was exceptionally long. Just as L-3 arrived, E-9 arrived; they were dispatched as soon as B-3 got his car jumped and responded to 3rd Avenue. Even with the delayed response, they still beat all the southern companies to the scene. E-9 went directly to the hydrant on the southeast corner of the complex. This hydrant was used in 2000, and we knew it had good water (or at least we thought we knew). Sq-7, a water tower, was next in. It was also rerouted when the 3rd Avenue assignment was reduced. I had the apparatus back in so we could make use of the waterway, and I had L-3 position just on the flank between the fire building and the attached D exposure. Another water supply was being established using E-4 at the head of the south side of the access road. We counted on using that water supply for Sq-7, but Chief Murphy showed up. We discovered that the hydrant near the river had been damaged by the hurricane and the steamer connection and side plugs were unusable (later, the side plugs would be gorilla’d off and used; initially, the pump operator could not get them off).

Adjustment time: We used the crews of E-3 and 4 and Sq-7 to lug the five-inch large-diameter hose (LDH) from E-4 all the way down to E-9, since lines from E-9 were already being stretched toward the fire area. This was about 100 yards; it took some time and delayed water to the fire. We normally use two engines to feed, doing supply and attack, but this hydrant choice had worked well in 2000, so there was no reason to expect differently today. E-9 would take that hydrant, and E-4 would take the next one, doubling the available water. Not today.

Additional Alarms and Establishment of Divisions

A third alarm was struck, followed by a fourth alarm. This fire would eventually go to six alarms, and, believe me, we needed every firefighter there for relief and reinforcement of the divisions. Each additional alarm brings in two engines, a ladder, and a chief. We can bring in North Hudson companies up to the third alarm. After that, we mostly rely on Jersey City and Hoboken who, although they are past our southern border, which created a large reflex time since this fire was near our northern border, bring additional chiefs, making it a lot easier to manage the incident.

Note: As B-3 was wrapping up the incident on 3rd Avenue, his car did not start again, and all the apparatus were on their way to the fire. Solving the problem, B-3 Chief Mike Falco flagged down a car and hijacked a ride to the fire.

To set up my fireground organization, I had the three North Hudson battalion chiefs who, on arrival, were immediately sent to establish divisions. As time went on, Chief of Department Frank Montagne arrived and took command. I was designated as Operations Section chief. I also knew that within the next two hours, the next day’s platoon would be arriving with four more chiefs and more than 50 personnel. The headquarters chiefs would also be coming on duty soon. This was great eventually, but at 0545 hours on that morning, I was requesting that all on-duty chiefs respond because I knew they were critical to the operational plan and strategy. I placed the first chief on scene, B-2 Bob Duane, in the fire building for recon with the first-arriving companies doing the primary search and attempting to find the fire as the initial attack line was being stretched.

They reported that although they noted heavy smoke throughout, they could not find the fire, and that the heat conditions on the second and third floors were worsening. I also noted the fire breaking through the wall between the first and second floors was intensifying. Based on these reports and my knowledge of the building (and the mental file cabinet provided by RPD), I ordered an evacuation of the fire unit and concentrated on using the same pincer action that worked so well in 2000. With orders to conduct an interior defensive operation, I placed B1 Chief Mike Giacumbo in charge of the Delta Division. I initially had my L-1 officer in charge of the Bravo Division doing a search and recon, but once B-3 arrived on scene, I assigned the Bravo Division to him with the same orders I had given to the Delta Division. It’s okay to make a captain a division commander, but as soon as you can, replace that command with a chief. B-2 was reassigned supervision of the Charlie Division, inside the horseshoe, where he was to operate at the rear and use defensive streams to deluge the fire area, which I was anticipating would collapse in a relatively short time. I then began to feed companies into the divisions and monitored their progress reports for signs that adjustments were needed. I also had companies operating at the Alpha side, where we set up Sq-7’s master stream and got L-3’s ladder pipe ready as well as deployed an additional manifold to supply some 2½-inch handlines. Eventually, we would place a deck gun in service on the A side as well.

WATER SUPPLY ISSUES

Because of the remoteness of the complex and the fact that a single main fed the complex off River Road, we recognized the need to relay water in to supplement our needs. As I said earlier, the first engine, E-9, which had hooked up to a bad hydrant, was being supplied by E-4. Sq-7 was being supplied by Sq-2, which was being supplied by E-13. E-13, in turn, was being supplied by a Jersey City engine out on River Road. The ladder pipe on L-3 was being supplied by E-9, which was also supplying a manifold near the Alpha side from which lines were being used both on the Alpha side and the Charlie side. The problem we were running into was the difficulty in getting water inside the horseshoe where the bulk of the smoke and fire was spreading (photo 5).

|

| (5) The pathway leading to the inside of the horseshoe was used to establish two five-inch water supplies. Later, the water supplies were established at the cliffs, way in the background, from where the water was relayed. (Photo by Ron Jeffers.) |

In 2000, the wind was blowing from the cliffs (west) toward the Hudson River (east). It made protecting the Delta exposure extremely difficult. At this fire, the wind was blowing from the Alpha side (south) to the Charlie side (north). It did not create the same problem regarding the wind-driven exposure problem we experienced in 2000, but it shrouded the Charlie side with thick, choking smoke, making visibility difficult (photo 6).

|

| (6) The conditions on the Charlie side of the fire (inside the horseshoe) were much smokier, as it was leeward of the fire. Access to individual units in this area was also difficult. Note the division commander-a critical piece of fireground command, control, and information. (Photo by Ron Jeffers.) |

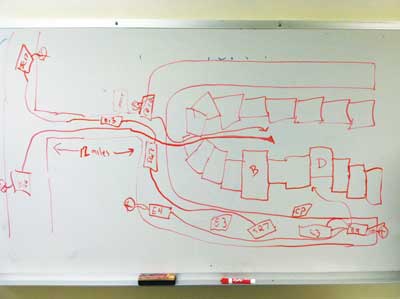

From a command standpoint, the need to get lines into the Bravo and Delta exposures was just as critical as in 2000, despite the wind direction. The reasons for this were that the buildings, which were prefabricated, were attached in most areas and the lightweight truss cockloft was open in spots. To address the issues of water on the Charlie side, we set up two more water supplies. The first was established by Sq-10 at a hydrant on the north side of the access road. They supplied a manifold inside the horseshoe. The Charlie division commander was still requesting additional lines, so a second relay was established (the fifth water supply in total) from River Road where North Hudson Sq-20 supplied a manifold to the inside of the horseshoe. At this point, I designated a water supply officer and gave him four companies to accomplish the task. It was a very long LDH stretch from River Road to the inside of the horseshoe, and it took time (photos 7-8).

|

| (7) Inside the horseshoe. Companies are bringing in the second water supply established in this area. It took time and several companies to accomplish. Always be thinking from where and how you will be getting your next water. (Photo by Ron Jeffers.) |

|

| (8) This crude drawing (not exactly to scale) was used for the incident evaluation. To the left of the drawing is River Road. To the right at the open end of the horseshoe is the Hudson River. The “12 miles” marking on the access road was a sarcastic joke aimed at the long stretches. It was easily 300 yards from River Road to the inside of the horseshoe. (Photo by Ron Jeffers.) |

VOID ISSUES AND INACCESSIBLE FIRE

In the 2000 incident, the fire was visible when we arrived; it was already in the roof void and eventually would burn off the roof. At this fire, the majority of the time, we were confronted with extremely heavy smoke from fire deep within the structure. The roof never burned through, and I was a little upset with myself that although I considered it on arrival, I did not order L-3 to cut a triangular hole in the roof (from the safety of the aerial). I don’t think it would have made a big difference in the end, but in my mind, it was a good tactic if done safely from an aerial device. Only after the collapses did the building begin to open up and show free-burning heavy fire. For this reason, operations in the exposures were difficult: The smoke was heavy, and there was fire on all three floors of the fire unit. At times, it did break into both exposures, but the companies assigned to those divisions beat it back. The division commanders had their hands full, and I accommodated them as best I could to supply fresh reinforcements and relief. Their assignment, which they handled beautifully, was to hold those exposures. They took it personally, knowing that if we gave them up, we might be chasing fire around the horseshoe. Again, because of access issues and water needs, there were delays in getting protective hoselines into the exposures, but they made do with what they had and, through combustible-clearing operations and, again, hard-nosed firefighting, made a great stand.

There was 5⁄8-inch gypsum board on wood studs between the fire building and the exposures, and although some of the master stream operation began to compromise the gypsum board and push the fire toward the Bravo side, the divisions were held. In fact, at one point, we did evacuate the Delta exposure based on reports from the Charlie side (that turned out to be false) that there was fire in the cockloft. Much like the fire in 2000, I used the experience of my safety officer and division commanders to assess the situation and assist me in the decision-making process. Fortunately, we were able to shortly reoccupy the Delta exposure and maintain our position there (photo 9).

|

| (9) Unlike the first fire, the fire did not break through the lightweight truss roof; it continued to eat away at the voids and lightweight flooring systems. (Photos 9-11 by Ron Jeffers.) |

COLLAPSES

If you are the IC here and are not anticipating that the lightweight truss roof and floor systems will collapse early, you are not getting it and are severely jeopardizing your personnel. You do not need RPD to be on top of this; your training and the recognition of truss construction should tell you enough to pull the troops out once the voids are involved. At the fire in 2000, the roof collapsed and pancaked the floors right into the garage, ripping the floor trusses of the lower floors (which were not damaged by fire) right out of the truss voids in the process. At this fire, the first collapse occurred relatively early. It was a floor collapse that dropped the three-story building down to a two-story building, opening up the side wall on the Delta side and exposing the trusses that were, again, ripped from their holders in the wall (photos 10-11).

|

| (10) The walls between floors began to separate, and the sides began to buckle as the floors began to collapse. The floor trusses came right through the side wall where the fire first appeared on arrival. |

|

| (11) The three-story structure that is now a two-story structure. |

The buildings here are not completely attached for their entire width; they are staggered so some of the front or rear Bravo and Delta sides are visible. You will have to look at the photos to see this for yourself; it is easier than trying to explain it. The second collapse, apparently another floor collapse, mirrored the first and dropped the building even farther. There were two parts to the unit. The original fire area was on the Delta side of the unit, and the other side of the unit was closer to the Bravo exposure. The Delta side of the unit collapsed first, opening up the area between it and the Bravo side.

At first, when we were accessing the structure, I thought that the Bravo exposure had been set up in the Bravo side of the fire unit, but once I saw the position of the Bravo division commander, I realized that the fire unit was wider than I first anticipated. Again, being at the rear of the structure (the command post was on the Charlie side of the building-the street side), I had a hard time telling where the units began and ended. The area I thought was the Bravo exposure was actually part of the fire unit that was separated into two apartments, right and left, and accessed by the same exterior stairway that led to the fire unit. Once I was made aware of this, I realized that we could not have properly defended what I thought was the Bravo exposure because its egress was the same wooden stairs we had used to access the other side of the fire unit.

The next collapse came a while later as part of the Bravo side of the unit came down, shortly followed by the rest of the remaining wall closest to the Delta exposure. These units were prefabricated and independently constructed, so the collapse of one did not affect the units adjacent to it. Fire spread, with which we were dealing, was the bigger threat. The final collapse occurred when the wall adjacent to the Bravo exposure (which was free-standing at this time) buckled and fell inward. There was some concern it would fall on the rear of the Bravo exposure, and we took precautions until it fell inward. Once this last collapse occurred, the exposure issues significantly improved, and the fire was well on its way to being under control (photo 12).

|

| (12) This view is from the Bravo exposure looking across the collapse toward the Delta exposure. Note the gypsum board and the open spaces in the truss cockloft. Again, a good pincer action with interior defensive operations in the exposures, supported by command and supervised by chief officers, made this stop possible. (Photo by author.) |

ACCOUNTABILITY

I eventually had nearly 150 firefighters and officers at the scene, one of the largest fire operations I have ever commanded, and because of their discipline and adherence to our accountability policies, I did not have one issue with a freelancer either individually or at the company level. I made use of personnel accountability reports (PARs) every 15 minutes or so. I used the divisions as the mechanism to conduct the PARs, as it was too difficult to run a roll call with that many people on the scene. I was relying on the company officers to maintain company integrity, and they did not let me down. I would radio each division for a PAR of its companies. They would in turn ask each company officer for a verbal accountability report, and they would report what companies they had with them and that all personnel were accounted for. This allowed us to update the command board regularly. It worked very well. Why? Because we had set the expectation well before the fire that anyone arriving on the scene or changing assignments would report to the command post before doing anything else. It made my job and the job of my command tech easier. We had a personnel staging area set up behind the command post and a Rehab Division set up near the entrance to the complex. I am extremely proud to say that everyone on scene, from our companies to the mutual aid from Jersey City and Hoboken, adhered to disciplined operations. All assignments should begin and end at the command post. If I know where you are, I can support you and keep you safe. If I don’t, your safety is diminished.

LESSONS LEARNED AND REINFORCED

Like the fire in 2000, we were able to successfully defend the immediate Bravo and Delta exposures, losing only the fire unit. It’s OK to lose one unit or building. Losing more than one when you could have stopped the fire’s progress through proper operations is unacceptable. The keys to success in 2012 and in 2000 were personnel, organization, communication, and discipline. Without any of these, the outcome would have been different. So what did we learn in 2012, and what was reinforced as being effective from the 2000 fire?

• Get people and equipment early. We went to six alarms, four in the first 20 minutes. Command is striving for three things: enough people to operate in the building (let’s call them Task Force 1); enough people to relieve them (Task Force 2); and the reality that at any given time, there will be people taking a break (Task Force 3), who will eventually be back in the game. My philosophy is that when the fire is still escalating, any time I have no one in reserve at the command post to put into the game, I strike another alarm. What I am striving for is to have people at the command post I don’t have to assign as soon as they get there. That creates my tactical reserve and stabilizes my on-scene personnel profile. Additionally, I have to realize that a third of them at any given time will be in rehab. Understanding the personnel needs that fit this “operating/rehab/ staging” cycle is the foundation for determining personnel needs.

• Hydraulic reserve. We used five water supplies at this fire. The topography of the area created some severe challenges for getting water to the fire, and we did some unorthodox things to get it done. If you are not anticipating future water needs, you will run out or you will be stealing from each other. We had great water at this fire. In fact, Sq-7 operated its water tower, supplied a deck gun and several large-diameter handlines, and still had a hydraulic reserve of nearly 50 pounds per square inch.

• Manifolds and deck guns. Work smarter, not harder. If I could do it over again, I would have had more ground-mounted deck guns on the Charlie side (inside the horseshoe) rather than using all that 2½-inch hose. In addition, rather than stretching miles of 2½-inch handlines from remotely positioned engines, stretch a five-inch LDH supply to a manifold and then stretch shorter lengths of 2½-inch hose or supply the deck guns. If you are going defensive, go for the big guns in the areas to which you cannot effectively deploy apparatus-mounted master streams.

• Water supply officer. If you need multiple water supplies, it is tough to coordinate that from the command post. Assign someone to get it done for you, and support that individual with enough personnel to get the job done.

• Division supervisors. This fire would not have gone the way it went (or would not have gone out at all) without proper decentralization of command. You can’t do it all by yourself. You will be overwhelmed. Instead of letting the chiefs hang out at the command post where all they will be doing is whispering how they can do a better job, deploy them to the areas in which you do not have direct control and support them with personnel and equipment. You will reduce your span of control, reduce the radio traffic, and save your sanity.

• PARs. Conduct PARs at regular intervals, and if you were smart enough to decentralize your command, use your division commanders to keep track of the companies in their divisions while you keep track of divisions.

• Rehab and staging. Control them, and your operation will go more smoothly. One of the things I wanted to do but didn’t was to put the Rehab unit about 100 feet behind the command post. That way, anyone coming from the building to Rehab would have to pass the command post; the same goes for anyone coming out of Rehab. In fact, your personnel staging area (people waiting to go into the game) should also be between the Rehab area and the command post. Make it easy for the companies to comply with your accountability needs by setting up Rehab somewhere near some type of corridor or easy access to the command post and personnel staging.

• Additional rapid intervention company (RIC) and safety officer. Big fires with a large footprint potential require additional attention to safety. We should have had an additional RIC and safety officer on the Charlie side but did not. Note to self: Don’t forget this next time!

• Try to cut the roof from an aerial. If you can get a hole in the roof, you will likely be able to thwart lateral extension a great deal. Just remember not to stick a master stream in the hole until just about all of the roof has burned off.

• Lack of rated fire walls. Lack of rated fire walls in this horseshoe-shaped building of lightweight construction made this fire difficult to contain and dangerous to firefighters.

• Fire in the truss voids = get out and stay out. If the only thing you learned from this article is this, I did my job. If you are unsure if lightweight construction is present, send someone to check by opening up an uninvolved section; then, based on the findings, operate accordingly (photo 13).

|

| (13) A roof truss bottom chord in the saved exposure. Once it is discovered and involved, if you are betting your firefighters’ lives on this connection, you are not getting it. Get them out. (Photo by author.) |

Endnote

1. Avillo, A. Fireground Strategies Scenarios Workbook, 2nd Edition. Fire Engineering, 2010.

● ANTHONY AVILLO, a 28-year veteran of the fire service, is a deputy chief in North Hudson (NJ) Regional Fire and Rescue, assigned as 1st Platoon regional tour commander. He has a BS degree in fire science from New Jersey City University (NJCU). Avillo is an adjunct professor at NJCU, teaching fire science. He is also an instructor at the Monmouth County (NJ) Fire Academy. He is an FDIC instructor and a member of the FDIC advisory board and the editorial advisory board of Fire Engineering. He is the author of Fireground Strategies, 2nd edition (Fire Engineering, 2008) and Fireground Strategies Workbook Volumes I & II (Fire Engineering, 2002, 2010). He was a contributing author to Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II (Fire Engineering, 2009) and is co-author of its Study Guide (2010). Avillo was the recipient of the 2012 Fire Engineering/ISFSI George D. Post Instructor of the Year Award.

Fire Engineering Archives