By Jeffrey A. Harwell

The article “Vacant Warehouse Fire: Lessons Learned” (Fire Engineering, June 2011, 59-68, http://bit.ly/19xXMkz) details a 1992 multiple-alarm fire in Fort Worth, Texas. I wanted to highlight the lessons firefighters learned in attacking a five-alarm fire in a vacant high-rise structure.

|

|

|

|

| (1) A typical two-story motel of modular design from which the facade was removed prior to demolition. The structure was 60 to 70 feet from the Fort Worth motel of the same design, the site of a three-alarm fire. (Photos 1-13 by author.) (2) The east side of the fire building after extinguishment. Note the heavy fire damage on the upper floors in the center of the structure. (3) Looking inside any motel unit, you would get the impression the building had been “undressed” and that you could tell exactly what is going on inside. (4) An arsonist tried to start a fire in a vacant first-floor motel unit (second unit from left in photo 1). The arsonist would later strike the building next door, igniting debris in the combustible utility space, resulting in the three-alarm fire. |

|

|

|

|

| (5) The combustible utility space in one Fort Worth motel building. The wallboard has been removed, leaving only the framing. A fire starting within this space will quickly spread vertically and horizontally. The wood planks at the bottom of the photo are laid on headers to avoid contact with the bare earth-there is no concrete slab. This would present a problem if a hoseline had to be advanced into this space. (6) The laundry, between the building’s exterior and the combustible utility space running along the center of the building; the utility access door is at the center. The exterior door is behind the photographer. (7) Inside the combustible utility space on the first floor, see the typical gap between two first-floor units for sound insulation. The concrete pads and the bare ground are visible at the center. (8) This view from the second floor looks down at the intersection of four modular units. The combustible utility chase extends from upper left to lower right in this photo. The gap that extends from lower left to upper right was the typical space provided between units for sound insulation. All wallboard was removed in preparation for demolition. |

When we hear the word “vacant,” we sometimes let our guard down because we assume any fire in a vacant structure will be minor because usually there are little or no contents or furnishings to contribute to the fire load. However, the construction methods used in one building design contribute to the fire load even when the building is vacant. Also, under certain circumstances, the very design itself delays firefighters from reaching the seat of the fire, which in some cases can lead to early structural collapse.

Three-Alarm Fire

To understand how firefighters typically discover this type of building design, let’s study the fire department response to a July 7, 1994, motel fire in Fort Worth, Texas. At 6:29 a.m., a first-alarm response was dispatched to a reported structure fire on the city’s far west side. As units responded, the dispatch office informed them that the fire was in the same abandoned motel complex that had been the scene of another working fire several weeks earlier. In that previous early-morning arson fire, the complex’s office/restaurant portion was destroyed.

When first-due units arrived at this incident, heavy fire was showing in one second-floor unit of the abandoned 50- × 143-foot, two-story motel. Units quickly stretched a handline and knocked down all visible signs of fire. Demolition had begun on this particular building. On each side of the structure, the façade (probably an aluminum and glass wall assembly) had been removed, exposing each room to the exterior. Thus, you got the feeling that you could look inside this structure from the exterior and feel confident that you could observe everything that was going on inside. So when crews knocked down the fire, they thought they had the fire under control.

Firefighters had been to several small fires in some of the motel units and the larger fire involving the office/restaurant, so they were familiar with the complex.

As firefighters were preparing to overhaul the latest burned-out unit, they noticed smoke conditions did not improve as expected. Heavy fire soon erupted in an adjacent unit, forcing firefighters to relocate and resume an offensive attack. As soon as this fire was contained, yet another unit erupted into flames.

As the morning progressed, more and more units began to flash over. At this point, firefighters realized they were at an extreme disadvantage because of some type of building construction feature that was spreading flames throughout the structure-yet the method of flame travel was hidden from view.

Having fought many apartment fires in which combustible chases and void spaces played a key role in fire spread, firefighters felt these factors were likely coming into play with the motel fire. Since command could not determine the exact method of fire spread in this situation and the motel was likely to be demolished, it switched to a defensive attack, emphasizing firefighter safety over the need to save a vacant building.

Second and third alarms were struck at 6:42 a.m. and 6:51 a.m., respectively, bringing additional equipment and staff to the scene. The defensive attack eventually controlled the fire but only after the building suffered severe damage. But the nagging question remained, How could a structure that was practically “undressed” and void of any furnishings have a three-alarm fire?

Motel Design

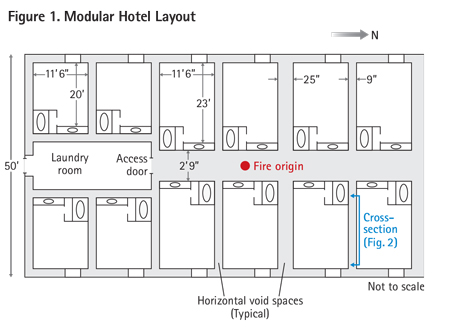

The design of this motel was similar to many others constructed in the 1960s and 1970s. Whereas today’s typical hotel model is three stories high with a center corridor and an automatic sprinkler system, the older design was typically only two stories high, with rooms that opened directly to the exterior and without an automatic sprinkler system. In a given building, there were two rows of rooms that backed up against each other (Figure 1).

This design provided a common utility void space along the centerline of the building where the rooms backed up against each other. This allowed the plumbing contractor to run all piping within this void. The bathrooms for all the units were situated along the back wall directly adjacent to the utility space, limiting any significant horizontal plumbing runs, thus saving money. The electrical contractor would also use space for electrical equipment and wiring.

Unfortunately, contractors never spent any money finishing out these void spaces, leaving all the wood 2 × 4s and the plywood roof deck at the top of the utility space exposed, thus creating a rather large combustible concealed space that had limited access (usually just an access door at each end of the space). The access door may or may not open directly to the exterior. There might be an intervening room (e.g., a laundry room) between the chase and the exterior. Thus, a prefire plan was critical in allowing firefighters to quickly locate these doors during a fire response.

Firefighters reading this would likely conclude that accessing this space early during a fire would allow for quick fire extinguishment. Although an excellent idea, this action alone will not solve all problems associated with this building design.

Modular Design

This particular motel design also incorporated the modular construction design. Each unit (motel room) could be constructed off-site as a modular unit, basically a wood box that was open on one side. It would be trucked to the site and hoisted into place. The bottom units would rest on concrete pads, each pad located underneath one corner of the unit. This meant there was no concrete floor slab, just a combustible void space between the floor joist and the bare ground under each room (Figure 2).

|

|

|

|

|

| (9) This header holds up the ceiling joists of a second-floor modular unit. The circular holes cut for utilities enabled horizontal fire spread. (10) For final extinguishment, companies had to pull all wallboard to reach pockets of fire in the combustible void spaces above and around the second-floor units. The circular utility holes allowed the fire to spread into the ceiling spaces above the second-floor units (see photo 9, Figure 2). (11, 12) At the Fort Worth motel fire, a floor/ceiling joist assembly collapsed because of damage from fire traveling throughout the void spaces between the joists. This collapse occurred with no live load inside-all rooms were vacant and without furnishings. (13) This view from the second floor looks down through the Fort Worth motel utility chase after the three-alarm fire. Modular units were situated on the left and right side of this chase. |

After construction crews added the second-floor room module, they would allow for up to a 25-inch horizontal gap between the adjacent units to the left and to the right, running vertically from the bare ground to the underside of the plywood roof deck. Designers liked this feature because of its sound insulating qualities. These smaller combustible void spaces provided yet another avenue for fire spread beyond the common utility space.

Once the fire traveled into the void spaces between rooms, it found yet another avenue of extension. The headers that supported the floor and ceiling joists of each unit had circular holes cut out to allow for running electrical wiring through in the future. Although this setup was convenient for electricians, through these holes, the fire could access the combustible void spaces in the ceiling space above both floors. This would create a dangerous situation for firefighters who might be inside the unit trying to cut off the fire extension. There have been cases, and this fire was one of those cases, in which fire damage to these joists was extensive enough to cause complete collapse of the floor/ceiling assembly. It’s critical for firefighters to keep in mind that they will have to perform extensive truck work when checking for fire extension in this type of occupacy.

|

|

|

| (14-16) In the Richmond County, Georgia, motel fire, fire crews constantly chased the fire throughout the incident. Every few minutes, a unit would flash over; crews would quickly knock down all visible fire there and then have to relocate when another unit flashed over. (Photos 14-21 by William Harwell, Jr.) |

In the Fort Worth motel fire, the combustible void space for utilities was 120 feet long and two feet, nine inches wide. An arsonist apparently piled up some debris and old furnishings in the void space and used a liquid accelerant to aid ignition. The doors at both ends of the void were open at the time of the fire, thus allowing a significant breeze to blow through the void space. The ample oxygen supply quickly intensified the fire, allowing it to spread vertically and horizontally.

Graphic Example

Photos 14-21 provide a graphic example of how a fire in this type of structure can quickly take possession of the entire structure despite firefighters’ best efforts. At 6:45 a.m. on January 4, 1991, the Richmond County (GA) Fire Department received a call for a structure fire at the Horne’s Motor Lodge.

The three engines, one aerial, and one battalion chief responding on the first alarm were directed to the “100 Building,” which was similar in construction to the “typical” motel design described above. The “100 Building” was vacant at the time of the fire, undergoing renovation. Some rooms had no furnishings; some had furniture and mattresses stored in them.

When first-due Engine 11 pulled up to the complex several minutes after dispatch, the crew reported heavy smoke showing with no visible flames. Crews immediately recalled a fire in the “Par Building” within the same complex a few years earlier with very similar conditions. Thus crews were already aware of the combustible void space for utilities and knew they had to quickly access this area with handlines to have a chance of quick extinguishment.

Despite firefighters’ repeated attempts to gain control of the main chase, intense heat drove them back, and they soon realized the battle had already been lost. Fire was already working its way horizontally and vertically into practically all the void spaces surrounding the module units.

Command requested a second alarm to provide additional staff. Extra personnel were also available when firefighters on the outgoing shift were held over on the fireground.

As is typical with this type of fire, units would flash over at various times and handlines would quickly extinguish them. However, the constant smoke conditions never let up as the fire continued to burn vigorously in the numerous void spaces.

Crews operated a ladder pipe and a deck gun at one point, but neither was highly effective. At various times, the smoke conditions would change from moderate to heavy, but the fire never broke through enough of the roof to allow the ladder pipe to be effective. Since the fire was confined to the void spaces for the most part, the deck gun was never able to effectively reach the fire in the confined spaces.

|

|

| (17, 18) Conditions on the fireground can change within minutes. The ladder pipe was ready if operations went defensive. However, since the fire was confined to the structure’s numerous void spaces, handlines proved the most effective method of extinguishment. |

|

|

|

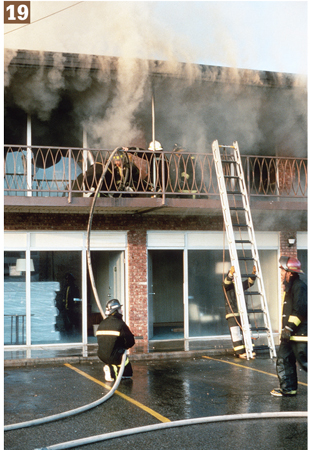

| (19-21) Firefighters eventually controlled the fire by going room to room, tearing into the walls and ceilings of each unit, and operating a fog stream into the void spaces. Note the mattresses stored in a bottom-floor unit in photo 19, indicating the rooms were undergoing renovation at the time of the fire. At the far left of photo 21, you can see a first- and second-floor door that probably leads to the combustible utility chase, which may or may not have an intervening room in front of it. |

Realizing there was no easy way to accomplish final extinguishment, crews began the arduous task of going from room to room, opening up all void spaces and operating a fog nozzle to extinguish as much fire as possible. This method proved successful in finally bringing the fire under control.

The fire origin was ruled accidental, caused by a maintenance worker sweating pipes in the utility chase the previous afternoon. Although there was heavy damage to the center of the structure and the void areas around each unit, there was never any major structural collapse. Damage was significant enough to result in the demolition of the entire structure.

Firefighting Tactics

As mentioned before, accessing the utility space during the early stages of a fire doesn’t necessarily ensure quick extinguishment. Later in the 1990s, another north Texas fire department faced the exact same scenario as those fires already mentioned-heavy smoke showing from a vacant two-story motel. Based on an existing prefire plan, firefighters knew the fire was located in the combustible void space for utilities.

Command ordered the placement of a portable deluge monitor in the access door leading to the space to try to quickly knock down the bulk of the fire and allow handlines to swiftly move in and start extinguishing fire in the remaining void spaces. Even with this method, operations were only moderately successful.

So what is the answer for a successful outcome? There may not be one. As a result of these fires, the most important consideration is that in each case, the buildings were eventually demolished. In two of the fires, the buildings were already slated for demolition.

Any tactic that could lead to a positive outcome for this type of occupancy involves a truly aggressive attack by firefighters on the interior of the structure. Command must weigh the risk to firefighters based on the specific conditions present. If the motel is occupied and search and rescue operations are underway, then the risk becomes necessary. Many times, however, the structure is vacant, and the risks will usually outweigh the gains.

One of the possible recommendations for fighting these types of fires is to quickly provide vertical ventilation over the utility chase to slow the horizontal fire spread. Although this tactic makes a great deal of sense, you have to keep in mind how the roof is constructed in these types of structures.

|

| (22) Note the access doors at the end of the motel, a tell-tale sign of modular construction. It also has a truss roof. (Photo by author.) |

In the modular design concept, the roof itself is only a thin membrane used to protect the units from the elements and is usually not designed for substantial loads. The thin plywood roof decking above the chase is not going to stay stable for very long. Each of the cases above involved a delayed alarm, so the roof above the chase was already becoming unstable by the time firefighters arrived.

Fire Prevention Options

Fire prevention is also a possibility for controlling or slowing a fire in these types of occupancies. If a building is retrofitted with an approved National Fire Protection Association 13, Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems, automatic sprinkler system, the combustible utility chase would have to be sprinklered. Few motels have the financial means to take this route.

Automatic detection devices in the utility chase tied to a fire alarm system are also an option. Proper maintenance of fire alarm systems in these types of occupancies has always been a problem. The nonair-conditioned utility space would dictate that only heat detectors could be used, which wouldn’t provide the early notification the fire service would desire.

Firewalls have been used in some existing occupancies to limit horizontal fire spread. Even if a solution could be found involving fire walls in the utility chase, the usual problems would still remain. Contractors love to punch holes in these walls, and then it’s up to the local fire prevention office to rigorously enforce proper repair and patching of these holes.

Preplanning

Most fire departments have a great deal of experience with emergency medical service calls. They continually respond to these types of calls and develop a high level of expertise. When it comes to working structure fires, these calls are much less frequent. Departments have even less experience battling a working fire in a vacant motel.

History has shown that prefire plans are crucial for effective decision making on the fireground. In the Fort Worth motel fire, a prefire plan didn’t exist, so command was in the dark with respect to how the fire was spreading. Luckily, the missing details were not critical to the incident’s outcome. If an occupant had been reported missing or if a firefighter had transmitted a Mayday, then the missing information would have become life threatening.

When confronted with a working fire in this type of occupancy, command must decide early whether an interior attack is needed and if it can be executed safely. If interior operations must be initiated, then extra staffing will be needed immediately. The bottom line: Fire departments must examine how they wish to attack a fire in this type of occupancy before it occurs.

Could this type of construction be found in your jurisdiction? I did a small survey while on a recent business trip to Oklahoma. I looked at four older motel complexes to see if any had possibly used modular construction. Sure enough, one complex (photo 22) had a building featuring access doors at each end, a tell-tale sign of modular construction. Hence, it is in the firefighter’s best interest to take a good long look at what is behind these doors during the next prefire plan. Although the odds of finding this type of construction in your jurisdiction aren’t extremely high, the chances of facing a challenging scenario should a fire erupt in one of these occupancies is extremely likely.

Jeffrey A. Harwell is a fire protection engineer based in Burleson, Texas.