By JEFFREY A. LATTZ

As firefighters, we’ve all attended training classes on building construction for the fire service. Fire departments and training programs usually follow curriculum that falls in line with state certifications and established books and publications. These classes and information are largely academic, consisting mostly of terminology and identification. Once you’ve completed the training, you’ll be able to identify a Type III from a Type V structure, some trusses, axial or torsional loads, and so on, but where do we go from there?

- Building Construction: Understanding Structural Loads and Loading

- Occupancy Classifications: An Orientation

- It Is What It Is, But What Is It?

Most firefighters agree that building construction is one of the most important topics (along with fire behavior) but still don’t feel confident about how to apply it or what to do with it when arriving at the fire scene. How are we looking at structures, interpreting or comprehending what we’re looking at, to help us make “real-time” tactical decisions? The traditional information is important to understand, but let’s explore a different approach to looking at buildings to perform better size-ups; have a better handle on what’s going on; and make better, safer tactical decisions on the fireground.

This approach brings into focus the types of things you need to notice or “see” to start making purposeful decisions and dramatically improve your situational awareness and personal safety as well as that of your fellow firefighters and civilians. Let’s not forget that most Mayday calls occur in single-family homes because of disorientation and/or being lost. A large percentage of firefighter fatalities occur in these unassuming single-family homes as well.

Making the Distinction on Arrival

The distinction between traditional “building construction” and “building comprehension” centers around learning how to recognize buildings by architectural type and proper name, exterior patterns that clarify the layout and floor plans, and building materials and construction methods that were used during that time period and applying this understanding to firefighting tactics. This approach is useful not only for single-family structures but also for multifamily low- and mid-rise apartment buildings, townhouses, and so on.

For the purposes of this article, I will explain how this approach can help you with these structures and demonstrate this by looking at a few specific examples. Following is a “tour” of a common type of single-family home and two very common types of multifamily buildings.

On arrival at the scene of a fire in a single-family home, most firefighters will size it up as such and provide a radio report including a brief description of it being a one- or two-story; possibly Type III, V or, more clearly, ordinary or wood frame; the conditions they see on arrival; and so on. This might help us create a radio report that sounds good or complies with a specific format and is relevant for initial size-ups but doesn’t necessarily help us with initial decision making.

When arriving first at a working fire, most firefighters are trying to suppress anxiety and not sound like idiots when giving radio size-up reports; this keeps them from noticing painfully obvious things right in front of them. However, if we learn some common types of homes and how to deliberately look for certain features, we can know the layout from top to bottom with 95% or better accuracy. Not only will you know the floor plan, you’ll also understand the era in which it was built and be able to anticipate construction features that are most likely present.

Once you learn some of these building types, you will develop instant recognition and be able to quickly make sense of the patterns, layout, and features. You’ll also be able to predict in what parts of the city they are found and “know” hundreds or potentially thousands of single-family homes in your city. For example, if a neighborhood was built out post-World War I (WWI), it will usually have three or four distinct house types. If you learn those, you’ll have a very good understanding of that area. To put this another way, if a Ford “muscle car” enthusiast goes to a car show and sees a few Mach 1 Mustangs lined up, he’ll immediately be able to tell which is the 1969 and which is the 1970 because he knows the design features and options of each. I encourage you to become a firefighting “enthusiast” in the same way. With that in mind, let’s look at one very common single-family home type: the American Foursquare.

The American Foursquare

I’m from the Midwest, and the American Foursquare is found in just about every city and small town that have areas built up just prior to and after the post-WWI period. Their “heyday” was from about 1910-1930, and they were built by the many hundreds of thousands, if not millions, in the United States. Even if this type is not found in your city or part of the country because of the era in which it was developed, this approach can work the same if you apply it to the types of homes you do have.

For example, if you work in a suburb that was built out in the 1950s and 1960s, you’ll likely have predominantly three to four different types of homes that won’t include the Foursquare. You can learn those distinct types and apply the same technique. Realize that there can be regional differences in vernacular, but that is not typically the case with the Foursquare. If you research these, you’ll find that this is the accepted name for these homes, getting their name because they’re two rooms wide × two rooms deep and stacked two stories tall, resulting in four rooms over four rooms. These homes are predominantly wood frame but can also be found in brick. It may be locally common to have more of one or the other. They are also recognized by their square shape being four rooms over four rooms, resulting in a footprint roughly 30 to 35 feet × 30 to 35 feet. They are a full two-story structure but never 1½ stories. I’ve never seen one in the Midwest without a full basement, so plan on that; there’s bound to be an exception to that rule somewhere because of the water table or something similar, but that would be very unusual for this type.

In addition, the American Foursquare most often has a hipped roof with at least one dormer on the front of the home, which is also usually hipped. It has a front porch that doesn’t wrap around the sides and that will also have a shallow, hipped roof. Occasionally, you’ll see some variation in the roofline that might take on more of the Craftsman style, resulting in a front gable and gabled dormer, but the textbook version is the hipped roof. Larger examples may have dormers on all four sides or a larger footprint, but the floor plans are generally the same.

Some (but not all) Foursquares are also potential candidates for balloon framing. I’ve been involved with construction work prior to, during, and after my career as a firefighter. I’ve seen platform homes built as early as the 1910s and 1920s during renovations. I recall one neighborhood where there were three Foursquares on the same block—two were platform and one was a balloon. In an old handbook1 I have for carpenters and builders on best practices, it clearly shows improved platform construction and fire stop techniques alongside balloon-framing techniques. For that method to be published, it was certainly being used by many builders, and this was back in 1911. The rationale was not only for fire stopping but also energy efficiency by blocking drafts. However, your best bet is to assume balloon framing until proven otherwise.

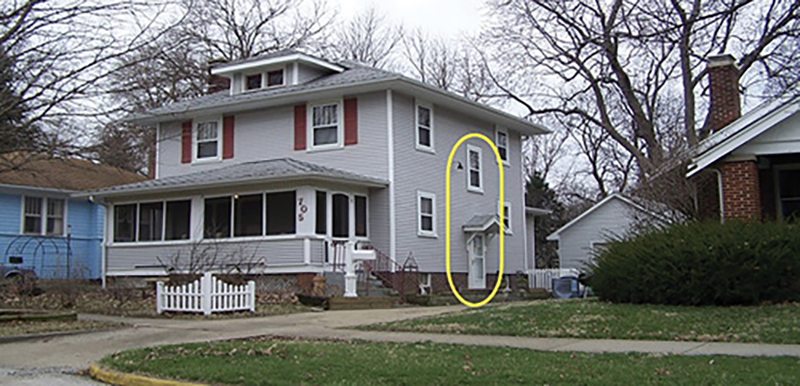

Once you learn how to correctly identify a Foursquare, you’ll need to look for two features so you can predict or map out the entire layout, top to bottom: the landing door and the window combination on the sidewall. Almost always, you’ll find it on one of the two sidewalls and every so often on the back. Let’s assume it’s found on the right sidewall (D side). You’ll recognize that the door is midway between floors as well as the window above it; this is all you’ll need to map it. That sidewall doorway will open to a stairwell landing. In this example, the top portion of the stairs will turn right going up about four to five steps into the kitchen. The bottom half will either go to your left or straight ahead and down into the basement.

You’ll also notice a sloped ceiling overhead to your left, which is the main staircase inside the home. In virtually all structures, stairwells are stacked since it’s the most efficient use of space. This means that the front (A side) entry door will direct you to the foyer/stairwell space on your right. The bottom half of the stairwell will hug the right wall (D side) ascending over the exterior sidewall landing door and hit the landing right where the sidewall window is located and turn left, going up the last few steps before reaching the second floor, more or less in the middle of the home. This will be a relatively small landing space that distributes you to each of the upstairs rooms. Don’t expect large hallways, as the home is way too compact for that.

The L-shaped, half-turn, 90° stairwell is by far the most common type of staircase found in a Foursquare. Occasionally on a higher end, larger Foursquare, you’ll find a U-shaped, full-turn, 180° staircase, which is predictable if you look at the landing window on the sidewall. If you notice a double-wide window or cantilevered landing window, anticipate a U-shaped staircase instead of the traditional L-shaped staircase. The double-wide window is there because the landing is twice as long. In this case, because it is a full return stairwell, the bottom half of the staircase will be pointed toward the center of the home and not hugging the sidewall; the top half of the staircase will be the same for both. The L-shaped variety will also be found in probably 90% to 95% of these homes.

Now that you know where the stairwell is located in this example, we know the living room is in the front left (B side) and often open to the stairwell/foyer area, possibly separated by some columns, pocket doors, or something similar. The dining room is always in the back on a Foursquare, placing it in the back left, and the kitchen is always behind the stairwell/foyer space. The upstairs will have a bedroom in the front right, another in the front left, and the third in the back left. The space directly over the kitchen will be the full bathroom and, depending on how large the house is, possibly a smaller fourth bedroom. Remember, kitchens and baths share plumbing walls back to back as well as stacked. For the same reason, a small half bath will typically be located on the first floor, adjacent to the kitchen.

Constructed in the 1910-1930 era, it is now known to the fire service as “legacy” construction. If you were to enter the basement on the above example, you’ll find that the load-bearing walls are on the right (side D) and left (side B) sides and in the center. The first-floor joists will be 2 × 10s and span to the center basement supporting brick wall or columns; this is because of the span ratings of 2 × 10s being approximately 15-foot depending on the wood species. Don’t expect to find an open basement as in newer homes, which use completely different building materials with longer span ratings. The second-floor joists will be 2 × 8s and span the same direction to the center load bearing wall. The attic joists will follow suit. Attic access will either be a scuttle or, in larger examples, possibly a walk-up.

Pay attention to the ceiling as you climb the stairs. If it’s sloped, you’ll immediately know if it’s a walk-up or not.

Once on the second floor, look around the corner for the walk-up entry door. If it’s a flat ceiling all the way up, you’ll need to look for a scuttle access. If it originally had a shake shingled roof, the rafters will typically be 2 × 4s (which will be the vast majority). The original sheathing will be one-inch boards with spaces between each board, which was the installation practice for shakes.

Often, you’ll see the original shakes in the attic under whatever modern shingle or roofing material is now present. You might also see the underside of oriented strand board as the “new” sheathing nailed directly over the original one-inch sheathing boards and shakes.

The roof pitch is typically about a 6/12; if it’s a walk-up, you’ll have to contend with an attic floor when ventilating vertically. If it’s a scuttle, you will almost never have to deal with that.

(1) The American Foursquare A/B corner. The circled entry door/landing window can be used to predict the floorplan. (Photos by author.)

A New Perspective

Now that you’ve learned what a Foursquare is, you’ll probably begin seeing them everywhere and will instantly recognize them and know the layout of their floorplan after locating the landing window/door combination. For that matter, many nondescript random frame homes, or “vernacular” homes, will incorporate a Foursquare type of floorplan. If you notice the features described above, you can begin anticipating what is the most likely floor plan with one of those homes as well. With this understanding, you can quickly determine which doors or windows lead to where. You’ll be better able to determine the best entry point for the lead-out; where to ventilate or ladder; how to predict the layout to significantly speed up the rapid intervention team (RIT) or search crew operations; as well as anticipate the types of construction features and building materials used and predict how fire behaves in them. Your confidence and situational awareness will improve dramatically, and you’ll be able to more purposefully and confidently apply tactics.

As a company or command officer, you’ll gain a much clearer understanding of what you’re looking at and comprehend what you’re hearing from interior crews. You’ll probably wonder how you’ve never noticed all these homes before and that, now, you basically can’t “unsee” it, but there they were, hidden in plain view the entire time. Using this approach can help you quickly interpret what you see and use it to your advantage.

You can use the same approach with many types of homes in your city. For example, you can develop the ability to instantly recognize a bungalow, Craftsman bungalow, Cape Cod, colonial, bi- or tri-level, and so on. Additionally, once you understand the era in which these were built, you can usually predict which three or four types are found in certain parts of the city and which aren’t.

If you’re responding to a fire in a neighborhood built out in the 1950s and 1960s; you’ll find bi-levels; ranches; and a few early tri-levels, which were becoming popular by the 1970s through the 1980s. You can usually rule out other types of houses and mentally prepare for one of these. After you learn the basic types and their names, this approach works well with almost all apartment buildings or multifamily structures. With that in mind, let’s explore two common, but very different, types of townhouses found throughout the country.

Two Types of Townhouses

When we think of a building called a “townhouse,” most of us conjure up an image of a two-story row house, which is basically true. We’ll look at those in detail and, for our purposes here, I’ll refer to those as a “standard” townhouse. However, there’s another type of townhouse known as a “stacked” townhouse that’s very different and will fundamentally change all our tactics once we can differentiate one from the other.

I use the term “party wall” to define the walls separating units when discussing apartment and multifamily buildings. I’ll also acknowledge the term doesn’t exactly extend to this context, by definition, but that’s the easiest way to think of the separations between units for tactical purposes.

After spending many years in construction studying apartment buildings and going to fires in them, your ability to recognize party-wall separations between units in any type of multifamily or apartment building is the single most important thing to figure out; all tactical decisions are based on your ability to do this. Generally, to recognize them, you’ll need to know what possible configurations exist, recognizing design patterns and construction symmetry. This is largely accomplished once you’ve learned basic types of apartment buildings and develop the capability to correctly identify them. You’ll also see logical patterns quickly emerge based on what type of building you’re looking at. Some types are easy to figure out; others are not. It’s critical that you have the self-discipline to take the extra time to figure it out before you commit to tactics or you’ll run the very likely risk of leading out to the wrong entry point, laddering windows firefighters can’t reach, ventilating areas that aren’t involved, wasting time searching portions of the building that aren’t high priority, or going above a fire and not realizing it. I’ve seen many fireground mistakes made (including some of my own) because of this lack of recognition and understanding.

Firefighters mean well and are possibly making decisions that are tactically sound, but their application or execution lacks because they “don’t know what they don’t know.” They might even be confident about it as they do it, which is easy to do when you’re unaware and don’t know any different. Keep that in mind as we look at the following two types of townhouses.

The standard townhouse. This is a building consisting of a row of units, each two stories, that share party walls only. A typical example might be a row of four townhouses. If you were to start on the left (B side), scanning across to the right (D side), on the first floor you’ll usually see a window, then a door, then a door and a window, and the pattern repeats for the next set. For a two-bedroom townhouse, you’ll see a single window over the front window/door combination, for a total of four windows visible on the second floor. If you go to the back, you’ll typically see a raised window on the right (B side), then a sliding patio door to the left of that, and then the unit adjacent will have that pattern reversed, and then it repeats. On the second floor, you’ll see another set of four windows, similar to the front; these are textbook two-bedroom townhouses. One bedroom has a window over the front (A side) and the second has a window in the back (C side). Thus, every visible window on the front or back belongs to a separate apartment in the two-bedroom variety. Also, the floor plans will most often be flipped or reversed to share plumbing walls.

(2) The front of a standard mixed-stack townhouse, with apartment numbers (A side).

In this example, if you were to enter the front door of the unit on the far left (toward the B side), there will be a straight-run stair to the second floor in front of you. The living room will also be in the front to your left. As you move through the living room, you’ll usually find a half-bath under the stairs and then a kitchen with a sliding patio door in the back. The utilities and a laundry area, if present, will be adjacent to the kitchen, again sharing plumbing.

As you ascend the stairs, you’ll be in the center of the building. You’ll find a bathroom over the kitchen, usually straight ahead and to your right in this unit because it’s typically sharing plumbing with the next unit in the row, just as it is with the kitchen below. There will be one bedroom behind you over the front door and the other on the back wall in front of you to the left. There may be hundreds if not thousands of these in your city or region of the country.

Just like the Foursquare, once you’ve learned about this type, you can develop instant recognition on arrival and can begin applying this knowledge. Knowing this, you will quickly realize your two entry-point options for the attack line, the only two accessible windows you can ladder, the number and location of bedrooms, search and ventilation priorities, and so on. If it’s confined to that one unit, the other three-quarters of the building aren’t a high priority—yet. If the incident grows because of a misunderstanding of the building type, misapplying tactics, or not anticipating fire development and spread, then the rest of the building will certainly become a part of the problem.

(3) The front of a traditional stacked townhouse, with apartment numbers (A side).

(4) The rear of a stacked standard mixed townhouse, with apartment numbers (C side).

The stacked townhouse. These townhouses look similar from the outside and are a type of rowhouse building, but they are not at all the same. In these buildings, the unit shares a party wall as well as a floor/ceiling. Each unit is a single-story “flat.”

One of the first things you’ll notice is that it looks like there’s a lot of front doors. If you go to the back side, you’ll notice it doesn’t usually have an entry or sliding patio doors quite the same way a standard townhouse does. You’ll also frequently see some type of framed staircase and doors or, sometimes, sliders stacked for the first- and second-floor units. Occasionally, there won’t be any rear doors and only windows. In that case, the one thing you will notice is that there aren’t any doors or sliders on the first floor like you’d find in a standard townhouse. One or the other may be more common locally. If you know this possible configuration exists, that’s half the battle. The next step is to recognize it and make the distinction because it will change all your tactics.

If you look at the front of the building, you’ll notice a pattern to the configuration of doors. If you started on the left-hand side (B side) and scan to the right side (D side), you’ll usually notice a window followed by a series of four doors then another window. There are a few variations, but this is a typical configuration.

Upstairs, you’ll see windows on the front side (A side), much like a standard townhouse. Of these four doors, two go to the first-floor units and two go to the upstairs units. Almost always, the two in the middle go up and over the lower units to the upstairs units. The door to the left of those two goes to the left-side first-floor unit, and the one to the right of those two middle doors goes to the right-side first-floor unit and then the pattern repeats.

The other thing you must figure out is where the party walls are located. If you don’t get that right, you’ll either need to get lucky or you will more than likely start making some tactical application or execution mistakes. For example, you must determine which window goes with which entry point. Much like the Foursquare, if you get this wrong and don’t understand these types of buildings, you’ll likely stretch an attack line to the wrong entry point, search the wrong areas, throw ladders to places that firefighters can’t reach, ventilate the wrong places, have a confused RIT, unknowingly get above fires, and so on.

Command officers also need to understand these buildings to comprehend what they’re looking at and understand the information they are receiving, be able to clarify the configuration on the fireground, apply tactics correctly, and send crews to the right places. If your city has both these types present and you realize or recognize the one you’re dealing with, announce the specific type over the radio during size-up. If firefighters have been trained on these two types and know their names, it will clarify and dramatically improve understanding and communication of what can otherwise be very confusing on the fireground.

(5) The rear of a standard townhouse, with apartment numbers (C side).

(6) The front of a standard townhouse, with apartment numbers (A side).

I’ve been to many fires in both townhouse types and have witnessed, more than once, confused firefighters who, in some cases, never figured it out until after the incident was over. It is also possible to have both these townhouse types in a back-to-back configuration as well has having both standard and stacked townhouses mixed in the same row or structure. This will change a few things on the upstairs windows, but the door configuration will generally be the same.

The back-to-back or mixed configurations are even more confusing, but after you grasp the concept, you’ll be better at interpreting and recognizing the meaning of certain patterns and features because you know these configurations exist. Just like with the single-family structures, you can use this approach to other buildings as well, such as a three-flat (triple decker on the East Coast), center hall, balcony type, garden type, and so on.

We should apply this type of approach to understanding buildings instead of only considering, teaching, or talking about traditionally taught building numerical types, trusses, loads, and so on. It takes a little patience and practice to develop this understanding, and you’ll need to develop a high level of proficiency with your fundamental skills and muscle memory to have the mental “freedom” to recognize these things in real time. However, you’ll find that this will dramatically improve your situational awareness, overall safety, and perception of things you never noticed before and you will be able to apply tactics with more purpose and confidence.

Endnote

1. Radford WA. Old House Scaled and Detailed Drawings for Builders and Carpenters. 1911. Dover Publications. 1983 reprint.

JEFFREY A. LATTZ is a 30-year fire service veteran who retired as a lieutenant from the Champaign (IL) Fire Department. For 24 years, he was a field instructor for the Illinois Fire Service Institute, where he is also the facilities operations coordinator, managing site maintenance and class support as well as focusing on design and construction of burn structures, props, and research simulators. Lattz has taught several firefighting classes including recruit academy, smoke divers, engine, truck, and Tactics I and II. His primary area of instruction is in building construction.