Several years ago, at the Fire Department Instructors Conference (FDIC) International, Frank Brannigan was standing outside the big room after his presentation, and I thought this was a great opportunity to ask an expert about a hot topic at the time: trusses, fire, and building collapse. I asked, “What is your opinion on how we should treat buildings with trusses during fire suppression operations?” At the time, the Hackensack, New Jersey, Ford dealership fire had recently killed five firefighters when the trusses collapsed. Brannigan always got right to the point, and this was no exception. He quickly said, “Did that building just land from Mars?” I replied, “No, the building in question has been there at least 30 years.” He then said, “Why don’t you know it has trusses? Good God, Jerry! Did that building just land from Mars?”

- Reconnaissance of Legacy Buildings

- Dissecting Buildings: Creating a Mental Blueprint

- Ciampo: The Oddballs

I wanted to shrink into the carpet as other firefighters eagerly looked on. Another valuable FDIC International lesson learned. Brannigan’s point was precisely on target: Why don’t we know about all the buildings in our first-due area?

One day after returning from FDIC International 2022, I relearned that lesson while we were preparing for a drill on an acquired structure. This building, a local gas station, had been in my town for many years. This article will show how, by simply being familiar with buildings in your first-due area, you can increase your chances of surviving a fire in that building—the building that did not “just land from Mars” but whose construction surprised you at the fire and might injure or kill you and your members. Surprises are never good on our fireground, and these surprises could cost you and your crews your lives.

(1) A typical service station. (Photos by author.)

Preplanning

Why did I not know? That will be the question you ask after one of your members is killed in action, during the funeral, and continuing through the after-action review. As much as we may not like it, it is a valid question that will be asked by the “Monday morning quarterbacks.” We are all familiar with recent and historical fireground construction catastrophes such as the Hackensack Ford fire (three died in the collapse, two ran out of air); the Waldbaum’s Supermarket fire in Brooklyn, New York; the Cliffside Park, New Jersey, bowling alley fire in 1967 that killed five firefighters; and many others. I cannot overstate the value of a simple walk-through of every building in your first-due area to familiarize yourself and your members with construction, occupancy, and life-threatening features that can kill you and your firefighters during a fire or emergency. We preach fire prevention for civilians—what about line-of-duty-death prevention for our members?

The second purpose of this article is to get you to think about preplanning, especially water supply for your larger (target) hazards. You know the location of the hydrants (no, they didn’t just land from Mars, either!); your responding units on first, second, third, and greater alarms; the location of drafting sites; how you’re going to run your tanker shuttles; and how you should coordinate and practice water supply operations, especially if water supply is a problem at your target hazard. Practice your plan on the classic “Sunny Sunday” so you are not surprised on “game day.” When you are running short on water, the exposures are getting ready to light up, and traffic is snarling your operation is not the time to figure it all out. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who planned the Normandy D-Day invasion, said, “The plan is nothing, but planning is everything.”

It is equally important to get to know your water company reps, who can tell you critical facts (i.e., strengths and limitations) about your hydrant system. Recently, my department worked with our water company engineers on a preplan. We learned that if we hook up two pumpers to hydrants nearest a target hazard [estimated required fire flows exceeded 5,000 gallons per minute (gpm)], this water district will provide about 1,700 gpm (that is, until we drain the water tank from the tank that supplies this water district—part of the larger system), after which we will get 0 gpm. We can hook up another pumper to other close hydrants, but that divides the available flow among three pumpers.

The next water district, supplied by other tanks/systems, is a half-mile away. Our pumpers can take it out faster than the water company can put it back in. Remember, the system is designed and operated for typical domestic use, not massive fire flows. Your hydrant system did not just land from Mars, either!

The Building

We acquired a building that was previously a gas station that was going to be demolished to make way for a bigger convenience market (photo 1). Our department and company officers conducted a predrill walk-through to determine the hands-on skills we could practice. Most of us, myself included, had been in the building before, but we would dash in to pay for gas or drop off or pick up our cars that were in for repairs and not think much about prefire planning. However, when we went in to look around to see what we could cut, force, shore up, and so on, the construction features shocked us.

A training evolution option we thought may be available was roof ventilation operations. Of course, during a real fire, the large bay doors will likely provide enough ventilation. As a training event, roof operations would give us valuable, realistic skills practice for our truck company members.

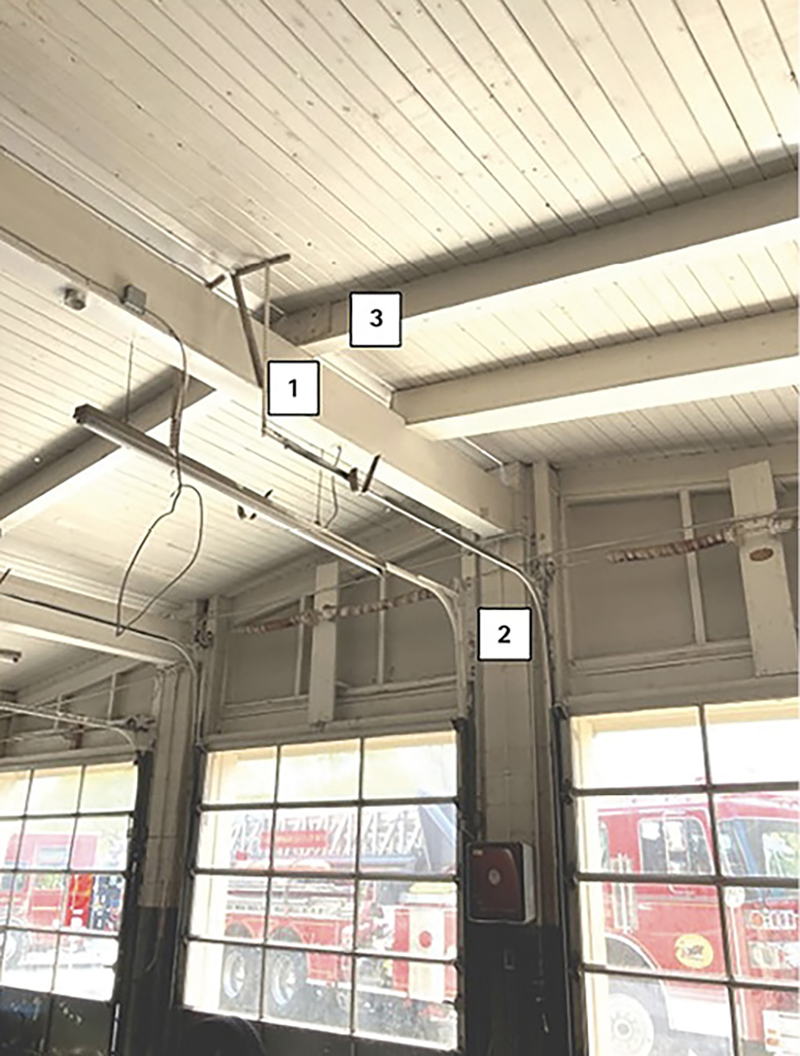

When we looked at the roof structure from below, we were shocked. Firefighters cutting the roof would be operating on a very weak, bouncy roof and have a good chance of dropping into the fire or, at a minimum, the hard concrete floor below as they cut. The roof was supported by a variety of construction methods and materials. A steel I-beam was boxed in with wood as one of the main structural elements [photo 2 (box 1)]. This was supported by a concrete block column between the bay doors in the front and the back wall in the rear [photo 2 (box 2)]. The I-beam supported the solid wood rafters that were widely spaced [photo 2 (box 3)]. The solid rafters were joined with a fish plate [photo 3 (box 4)] at the peak of the roof. Heavy reels of lubricating grease were suspended from the I-beam. Under fire conditions, these could drip hot oils and grease onto firefighters below. Connections to their supporting structures should always be suspect when being subjected to fire conditions.

(2) Roof construction prevented us from using it for training.

(3) This is a view toward the rear of the bay area showing the enclosed steel I-beam and the connections of the two solid rafters.

The Roof

The roof sheathing was tongue-and-groove (photo 4), and the rafters were widely spaced (photo 5). If firefighters cut a vent hole in the middle of this wide spacing, it is very possible the cantilevered roof decking would fail and drop them into the floor below. Depending on the depth of your cut and the type of saw you are using, cutting the solid rafter is a possibility. This would also likely drop you and your vent crew to the floor below.

Roof coverings had been removed prior to demolition and electric service was cut prior to our accessing the building. When we (carefully) climbed onto the roof, we found it spongy and bouncy, as you would expect. Also consider that water damage and rot of the lightweight sheathing will further weaken the roof, especially under the load of several active firefighters, again with unpleasant results for us.

(4) Tongue-and-groove roof sheathing.

(5) Note the wide spacing of the rafters supporting the tongue-and-groove roof sheathing.

Lessons Learned

Following are lessons learned from this incident.

- The value of knowing the construction of buildings in your first-due area is a major factor in our safety and fireground success.

- Although buildings like this one are safe and secure under normal conditions, fire department operations such as roof venting may prove fatal.

- Computers are nothing new to the fire service and can provide valuable building information data on receipt of an alarm for that building. Go out into all the buildings in your first-due area, collect information, and make it available to your first-due units so you and your successors can make intelligent decisions on the fireground.

- It is helpful to learn more about the works of Jack Murphy and Jerry Tracy in Fire Engineering on how to capture and use vital building information to help make our operations successful, safer, and more effective for our members. During a recent webinar, Murphy stated, “Doing proper inspections can reveal critical response information as well as help mitigate dangerous situations before they become tragedies. The companies doing the inspections can make life-saving contacts and develop extremely valuable relationships with building owners and tenants. Using a well-developed system, responding crews can access created histories and information, which can be invaluable in an emergency.”

- Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department District Chief Tim Kreis explains the long-term building life cycle and its effect on us: “The buildings and occupancies we are sworn to protect in our communities don’t just land here from Mars, then return there. In most cases, when structures are built, they remain within our communities for a hundred years. During the life of these buildings, the occupancy may change along with their interior contents and other factors. The exception to this is when they’re demolished and replaced for the next bigger and better building, or when they are consumed by fire. When we respond to structure fires, we evaluate the incident based on our previous experiences; what we see; from reconnaissance reports; and, most of all, from preincident planning.”

Get out into your first-due area; walk through one building each day. Use your emergency medical services runs to provide a valuable opportunity to conduct a rapid internal and external 360° size-up before the fire. Capture that important data on building information cards and make it available electronically on dispatch. These simple actions will help prevent fireground surprises and minimize the number of your firefighters killed in action.

Author’s note: Special thanks to Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department Shift Commander/South Deputy Mike Schamadan for assisting with this article.

JERRY KNAPP is the chief of the Rockland County (NY) Hazmat Team, has a degree in fire protection, is a 46-year veteran firefighter/emergency medical technician (EMT) with the West Haverstraw (NY) Fire Department, and is a former paramedic. He served on the technical panel for the UL residential fire attack study. Knapp is the co-author of two Fire Engineering books: House Fires and Tactical Response to Explosive Gas Emergencies. He is the author of numerous articles in Fire Engineering and state, national, and international fire service trade journals and the author of the Fire Attack chapter in Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II. He retired from the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, where he served as the plans and operations specialist at the Directorate of Emergency Services.