BY JACK SULLIVAN

Sixteen years ago, I wrote “Safe Response to Highway and Traffic Incidents” (Fire Engineering, June 2001), which covered the hazards of working near moving traffic and the ways emergency responders could mitigate the scene dangers and operate more safely. I wanted others to avoid my fire department’s 1998 experience on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. An out-of-control tractor trailer struck eight firefighters and two emergency medical technicians (EMTs) at the scene of a “routine” single-car crash on the highway shoulder. Nine personnel were injured, and Firefighter Dave Good did not survive.

(1) Photo courtesy of the Grand Rapids (MI) Fire Department.

Sadly, in 2017, the topics and key talking points for highway operations haven’t changed much. More distressing, the number of struck-by-vehicle fatalities and injuries continues to outpace our efforts to protect firefighters on the highway.

On December 9, 2017, a firefighter was fatally struck by a vehicle on Interstate 270 in Montgomery County, Maryland. He was in his personal vehicle when he stopped to aid at a single-vehicle accident in the fast lane. He used his vehicle to block the disabled car and put on his flashers. As he and the driver stood on the shoulder awaiting further assistance, they were struck by another vehicle and thrown over the highway divider into oncoming traffic. Both died. Through November 2017, fire/emergency medical services (EMS) personnel have suffered 11 line-of-duty deaths (LODDs) and the deaths of three off-duty fire/EMS personnel who stopped to help along a highway and were struck and killed. That’s the highest number of fatalities we have seen in years. What has changed? Why isn’t the record better? Why are firefighters dying at road and highway incidents?

Among the most consistent contributing causes of these highway response LODDs are the “D” drivers, who are drugged, drunk, drowsy, distracted, disturbed, disgruntled, disrespectful, or just plain dangerous. There are more D drivers on the road today than there were 16 years ago. Many have a “me-first” attitude—they will do whatever it takes to be the first in line, first to the next exit, first to peel away from the traffic light, and first to disregard directions from emergency personnel working an incident scene. They drive too fast for conditions in wintry, foggy, or rainy weather or when the sun is shining in their eyes. They have passed emergency vehicles responding to emergencies and have passed emergency personnel and apparatus operating at incident scenes while also trying to capture pictures or video on their smartphones; they are not watching where they are going. They disregard temporary traffic control devices; ignore personnel directing traffic (including police); and, on some occasions, have driven at high speeds into emergency vehicles parked at incidents with flashing warning lights and high-visibility graphics that most people can see from a mile away (photo 1). If you respond to roadway incidents in your area, most likely you have met some of these D drivers with some close calls vividly stuck in your mind.

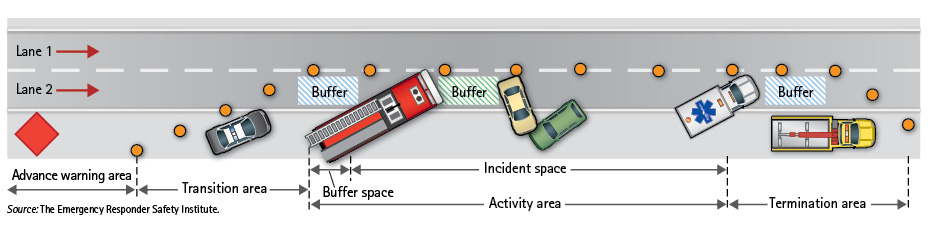

Figure 1. Traffic Incident Management Area (Temporary Traffic Control Zone)

The government is convinced that autonomous vehicles will solve the problem of ever-increasing deaths and injuries on our nation’s highways. Not in my lifetime. There will be a lengthy period in which the old technology vehicles we drive today will interact with newer autonomous vehicles. That will present even more challenges as we struggle to find even better ways to protect our personnel operating at roadway incidents. We’re still trying to figure out what some autonomous vehicles will do when they encounter emergency personnel manually directing traffic at an incident scene. I’m not sure if even the engineers designing those vehicles know for sure what they will do at incident scenes. Time will tell.

(2) Photo courtesy of the Emergency Responder Safety Institute.

In the meantime, we need to ratchet up our efforts to train and protect our firefighters and EMTs who are responding to roadway emergencies today. The key points below are similar to what I introduced 16 years ago.

• Developing SOPs. Develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) for highway incidents and use them to train your personnel about the hazards and strategies and tactics for operating as safely as possible given the environment we have to deal with today. National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety, Health, and Wellness Program (2018 ed.), is now available and includes a new chapter about traffic incident management (TIM). Chapter 9 of NFPA 1500-2018 includes requirements for SOPs, training, collaboration with other responding agencies, high-visibility garments, blocking apparatus, and proper positioning of fire apparatus at roadway incidents, among other things. Be sure to review the new standard when drafting a new SOP or reviewing an existing set of procedures in your fire department.

Another document you should consider when drafting SOPs is the Federal Highway Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) or your state’s specific supplement. Some states have their own version of the MUTCD; your SOPs had better be in line with federal, state, and local regulations. Are there any regional TIM procedures in your area? Include those guidelines too. Use your SOPs as the basis for initial training and annual in-service training for your firefighters and emergency medical personnel. Make sure they understand the hazards traffic presents and the ways to operate in a defensive manner to protect everyone on scene. Consider doing some joint training each year with the other agencies you work with at roadway incidents. Tabletop exercises are a great way to train with multiple disciplines. Also, use tabletop drills to review recent incidents to provide positive reinforcement for good operations and to improve any trouble areas that develop at some incidents (photo 2).

• Interagency cooperation. Collaborate, communicate, and cooperate with the other agencies you work with at highway incidents, especially law enforcement. Make sure everyone is aware of each agency’s SOPs, and work to ensure all personnel work smoothly with all other responders on scene. Participate in local and regional TIM committees and contribute to their goals and objectives.

• Emergency vehicle positioning. Teach your officers and driver/operators how to position fire apparatus and other emergency vehicles at incident scenes to provide effective blocks to protect victims and responders. Angle the apparatus with the front wheels turned away from the work area. Blocking apparatus are our best defense against D drivers who are not paying attention to where they are going (Figure 1). If you need to staff the pump panel on the driver’s side of the engine, angle the rig to the right. This puts the pump operator in a more protected position from oncoming traffic. Deploy chock blocks for your apparatus and secure vehicles that are on fire on arrival. There are numerous examples of vehicles on fire moving after firefighters arrive on scene. In some cases, they have rolled away from firefighters; in others, they have rolled into fire apparatus. Do your department’s training and procedures address that exposure?

• Traffic control devices. Encourage the deployment of temporary traffic control devices at incident scenes such as retroreflective warning signs, cones, flares, and advance warning vehicles where available (police, fire-police, or safety service patrol vehicles). Try to warn the motorists who are paying attention that there’s trouble ahead and to watch for directions from personnel on scene. The MUTCD designates pink fluorescent warning signs (photo 3) for use at highway incidents; agencies that use them frequently indicate that they do a good job of getting people’s attention. Where else do you see fluorescent pink anything on the highway?

(3) Photo by author.

• LED lighting. LED emergency lighting provides brilliant beams of light. However, we have also heard loud and clear from many drivers (especially truckers) that the newer LED lights are too bright at night and often blind drivers as they approach our incident scenes, especially when there are multiple emergency vehicles displaying every color imaginable. Drivers cannot see firefighters and other responders operating around stationary emergency vehicles displaying bright warning lights. Bigger, brighter, and faster flashing LED warning lights do not necessarily make our scene safer. When was the last time you drove up on an emergency scene with lots of flashing lights operating? Try it sometime under controlled conditions to see how motorists perceive our incident scenes. Warning light manufacturers are starting to address these issues and now provide design features like high/low power switches so warning lights can be dimmed a little at night. They are still very visible but they don’t blind approaching motorists. Some warning lights have built-in ambient light sensors so that the intensity of the lighting is adjusted automatically without operator involvement. The driver/operator may have to adjust the older lights manually. Make sure that’s part of driver training.

(4) Photo by author.

Remember, our emergency lights simply warn motorists that we’re there; they do not direct motorists where to go or how to pass the scene safely. Full-size arrow boards do that very effectively. Do not depend solely on smaller traffic directional lights found on the rear of many fire units. They are too small to be effective in most cases, especially on high-speed, limited-access highways. If you do install arrow devices on your fire apparatus, position them above the hosebed for maximum visibility (photo 4). Areas lucky enough to have transportation agencies, safety service patrols, or fire-police units responding to roadway incidents to set up traffic control can vouch for the effectiveness of full-size arrow boards (photo 5).

• Personnel visibility. Equip your personnel with high-visibility personal protective equipment (PPE) for use while operating around moving traffic. Crews should be wearing NFPA-compliant turnout gear when fighting fire on the highway. Most high-visibility vests and garments are not designed for proximity firefighting and should not be worn when personnel are exposed to fire, flame, heat, or hazardous materials. Personnel not fighting fire should wear high-visibility garments that comply with American National Standards Institute (ANSI) 107, American National Standard for High-Visibility Safety Apparel and Accessories. The newest edition of the standard, ANSI 107-2015, now incorporates ANSI 207, Public Safety Vests. Public safety vests are now known as Type P, Class 2 or Class 3 garments in ANSI 107-2015. Ask for garments compliant with the most recent edition of the ANSI 107 standard when ordering any new gear. If your older high-visibility garments are still in good condition, it is still acceptable to wear them until it’s time for them to be replaced because of wear and tear or fading of the fabric.

(5) Photo by author.

• Apparatus safety at the scene. A number of struck-by-vehicle fatalities in the past three years have involved firefighters who were struck by fire apparatus moving at an incident scene. In most of those cases, the apparatus was backing up. Teach your personnel proper procedures for backing up apparatus under all circumstances. Develop procedures for your personnel to follow when backing up apparatus at the scene. They should cover the use of spotters, audible communications between driver/operators and spotters, hand signals, and the use of mirrors and onboard cameras where available. A template for a “Backing Fire Apparatus SOP” is available for free at http://www.respondersafety.com/Resources/SOPs_SOGs.aspx.

(6) Photo courtesy of the Emergency Responder Safety Institute.

• Yielding to emergency vehicles campaign. Every state now has a law that requires motorists to move over or slow down when approaching emergency vehicles parked on the roadway and displaying flashing lights. Fire departments must educate the public about how they are to operate around emergency vehicles responding to an incident or parked at the scene of an incident. Consider providing in your fire stations handouts and displays for visitors (photo 6). Offer to do community outreach presentations to explain to people the dangers we face on the highways and how they can help prevent secondary crashes. Consider including roadway safety among your topics during Fire Prevention Week and open-house events, submit articles for your local newspapers, display message signs at your stations (photo 7), and work with local cable service providers and television and radio stations to develop and present public service messages about the subject. Be creative!

(7) Photo courtesy of the Emergency Responder Safety Institute.

Our firefighters and EMTs are exposed to moving traffic on every emergency and routine response—every one! When you step out of your rig, you are stepping into harm’s way whether it is in a shopping center parking lot, on a residential street, along a back-country road, or on the side of an interstate highway. We must operate on every run as if drivers are out to get us. D drivers are a hazard we can’t eliminate, so we must operate defensively and use every tool available to warn motorists and protect our personnel and the victims we were dispatched to assist.

The roads and highways in your first-due area are some of the most dangerous work areas you will encounter regularly. Prepare, train, and coach your personnel on safe operating procedures so everyone gets to go home at the end of the day. Always watch your back on the roads and highways.

RELATED

SAFE RESPONSE TO HIGHWAY AND TRAFFIC INCIDENTS

References

Emergency Responder Safety Institute. www.respondersafety.com.

Firefighterclosecalls.com. December 9, 2017. http://bit.ly/2j2CXVb.

Minihan, Bill. “Lest We Forget: Remembering the Pennsylvania Turnpike Tragedy, March 9, 1998.” www.Lionvillefire.org. http://bit.ly/2BoVRQY.

Respondersafety.com. http://www.respondersafety.com/Resources/SOPs_SOGs.aspx.

Sullivan, Jack. “Highway Incident Safety: The Hits Keep Coming!” fireengineering.com.

Sullivan, Jack. “Highway Incident Safety – They Are Not Just Routine Calls!” Fire Engineering Webcast. http://bit.ly/2AJnxR6.

Sullivan, Jack. “Safe Response to Highway and Traffic Incidents.” Fire Engineering, June 2001. http://bit.ly/2o93LII.

JACK SULLIVAN, CSP, CFPS, is the director of training for the Emergency Responder Safety Institute. He retired as a lieutenant and safety officer from Lionville (PA) Fire-Rescue. He has more than 30 years of experience as an instructor and works on various national committees dealing with traffic incident management and roadway incident safety for the fire service. He is also a Master Instructor for the FHWA SHRP2 Traffic Incident Management Train-the-Trainer Program.