By DAVID BRASELLS

It is 10 a.m. on a typical Tuesday morning. The rigs have been checked off and staffing for next shift has been submitted. Breakfast is over, all has been cleaned up, and the crew is ready for the balance of the 24-hour shift. The high-low tones blare out of the speaker, and the units, address of the emergency site, and type of call read across the LED reader board: “A 53-year-old female is having difficulty breathing, and Engine 1 along with Medic 1 are responding to 123 Fairview.” The crew arrives and helps Miss Smith, who needs a breathing treatment but refuses transport. The driver of Engine 1 notices the smoke alarm near the kitchen is missing, but he doesn’t mention it to the others. Engine 1 and Medic 1 tell Miss Smith to call them back if she needs further assistance and to be sure to get her inhaler refilled to avoid complications.

The Second Part of the Story

This is just another routine call you can relate to, right? Well, here’s what happened later. On Friday at 6 p.m., the steady low tones sounded three times and were followed by the automated voice that dispatched Engine 1, Engine 4, Truck 1, Rescue 1, Battalion 1, Medic 1, and Safety 2 to 123 Fairview for a structure fire.

Engine 1 arrived and announced, “Single-story residential structure with heavy smoke on Alpha side, front door open. Resident collapsed in front yard. Engine 1 is passing command and pulling a 1¾-inch line for attack. Next-due engine, secure the water supply; a plug is two houses down on the Delta side. Medic 1, you have a patient in the front yard.”

Medic 1 revived Miss Smith, who had quit breathing when she was overcome with excitement from the fire. Medic 1 transported Miss Smith to the hospital. The attack group entered through the front door and found heavy fire in the kitchen. The fire was knocked down and extinguished. The kitchen floor gave way, and one firefighter broke his ankle. A second medic unit arrived and transported the injured firefighter.

The Investigation and Critique

The fire investigator arrived and collected information from Battalion 1, who conveyed that Miss Smith had placed a pot of oil on the stove to fry okra when her sister called. She went out on the front porch to talk to her sister and forgot about the pot of oil on the stove. The fire investigator noticed that the smoke alarm was missing from the kitchen area and asked the crews if they removed it or know what happened to it. The driver of Engine 1 said that he noticed it missing when they were there earlier in the week.

Does this call sound familiar? As you followed the links in this event, which of them do you think would have drastically improved the outcome for all if it could have been removed? Obviously, it has to do with the smoke alarm in the kitchen. If the driver had mentioned that it was missing when he noticed it on the medical call made earlier in the week, the firefighters could have replaced it since they carry smoke alarms on the rigs. Miss Smith most likely would have heard the smoke alarm sounding while talking on the phone with her sister, and the fire likely could have been averted. She would not have passed out, and the firefighter would not have been injured. In addition, there would not have been $65,000 worth of structural damage to the house, a $15,000 emergency room bill for Miss Smith, and a $150,000 injured-on-duty claim for the injured firefighter.

The Stress Toll

But, what about the stress to first responders caused by this call? The driver of Engine 1, John, who has 30 years on the job, is kicking himself for not saying something about the missing smoke alarm. He feels responsible for his buddy’s broken ankle and for the fire damage. John has seen things over the years he cannot “unsee.” Each of those times, he was able to place the “unwinnable” situation in a closet and shut the door. John is looking at retiring in six months and wonders how he’s going to be able to keep the door closed on his closet of “unwinnable” situations when he doesn’t have to report for duty every third day.

First responders have been dealing with suicides among their colleagues at a rate higher than that for line-of-duty deaths. Captain (Ret.) Jeff Dill,1 who has a master’s degree in counseling and is the founder/CEO of the Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance, states: “While looking at our research, the indications coincide with our belief of ‘cultural brainwashing.’ The contributions of the job and stress from life raise mental health issues whose resolutions often conflict with the culture of the fire service.”

This culture emphasizes that firefighters should always be strong, courageous, and brave, which implies that firefighters should keep these issues to themselves, not share them or seek help. This is difficult to do when we witness what we do on our responses and also have to cope with what life deals us. According to Dill, the Alliance’s data show that the top contributors to firefighter suicide are marital/family relationships, depression, medical/physical health, addictions, and diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Analysis

When delving into this multifaceted challenge, I followed the advice of Simon Sinek,2 who believes that asking “why” instead of “how” or “what” enables leaders to inspire more action among their subordinates. Sinek explains that people buy “why” you do something more than what or how you do it.

Surveying first responders on social media and by e-mail, I asked the following questions:

Why did you become a first responder?

Their replies (I received 505 responses; most of the respondents have been on the job for more than 20 years) are in Figure 1.

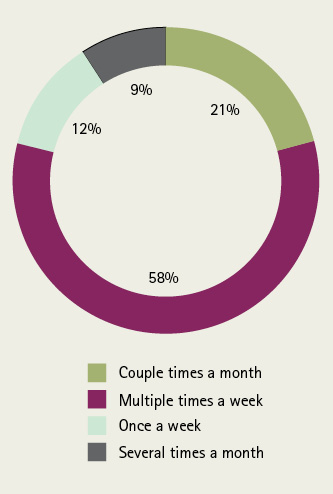

How do you deal with “unwinnable” situations?

The majority (59 percent) noted that the job leads to depression and that it derives from responding to a situation that has failed and over which we have no control. The phenomenon of helplessness is nothing new in our culture. Often, an attempt to fill the void felt from a sense of helplessness creates an addiction that is as bad as or worse than the void. The despondent person is sucked into a whirlpool of helplessness and addiction that may lead toward suicidal tendencies.

In his article “The Poison We Pick,” Andrew Sullivan3 writes that America’s ongoing addiction to opiates reflects that “society as a whole is trying to escape. The focus for drug use is not euphoria like perhaps it was in the 1960s but escaping reality … checking out.” Sullivan shares that during the Civil War, opiates were used not only for excruciating pain but also for rampant dysentery, which led to soldiers becoming addicted. The addiction was nicknamed “Soldier’s Disease.”

After the war was over, Americans turned to opiates to cope with the postwar issues of loss of family and the changing job market caused by the Industrial Revolution. Now, we have another change from industrialization to the Information Age. Small-town America is facing ever increasing opiate addiction levels. “The scale and darkness of this phenomenon are signs of a civilization in a more acute crisis than we know, a nation overwhelmed by a warp-speed, postindustrial world, a culture yearning to give up, indifferent to life and death, enraptured by withdrawal and nothingness. America, having pioneered the modern way of life, is now in the midst of trying to escape it.”

Figure 1. Why Respondents Became First Responders

Sullivan observes that Americans are choosing a drug that is a downer and not something that helps them engage in life. He concludes: “If Marx posited that religion is the opiate of the people, then we have reached a new, more clarifying moment in the history of the West: Opiates are now the religion of the people. A verse by the poet William Brewer sums up this new world:

‘Where once was faith,

there are sirens: red lights spinning

door to door, a record twenty-four

in one day, all the bodies

at the morgue filled with light.’”

It is ironic that one of the “failures” to which we respond on a regular basis is an opiate overdose. Repeatedly making overdose calls builds stress when you want to make a difference and yet continually see the addictive behavior you are powerless to change. Thankfully, many fire departments (70 percent of responders’ departments) are offering critical stress management programs to help each other with stressful incidents. Furthermore, survey respondents (70 percent) said they regularly turn to activities unrelated to first response to help alleviate stress from the job (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Respondents’ Use of Outside Activities to Relieve Stress

Community Risk Reduction (CRR): a Remedy?

There may be another antidote to the stress of the job that often leads to depression, PTSD, and suicide. When America Burning was published in the early 1970s, community risk reduction (CRR) was cited as a necessary tool to reduce injuries and deaths from residential structure fires. In 1987, America Burning Revisited proudly reported a significant reduction in the number of residential structure fires; however, the number of civilian injuries and deaths from fires continued to place the United States in the top 10 worldwide. For the most advanced society to continue to see on average 3,000 civilian fire deaths per year means we still are not reducing the community risk to the level of our capability to do so.

My colleague Deputy Chief (Ret.) Mike Wallace summed up our emergency response in a sobering manner: “When we respond lights and sirens, we are responding to a failure—a failure in education and/or a failure in the system.”

In the survey, first responders were asked if their organization offered CRR programs and, if so, if they participated in any CRR programs and why they did so. Close to half of the respondents to this question (43 percent) said their organization offered CRR, and 64 percent of this population said they participated in the programs. Among their “why” answers for doing so were the following:

- Prevention is more effective than response.

- It helps me with my own addictions.

- It is so rewarding to prevent bad things before they happen.

- To reduce the stress for first responders.

- Well-being.

- I have PTSD, so I am diligent in doing anything I can to keep it in check.

- I strongly believe this is the most important and proactive approach first responders can take at this time.

- It is good to interact with the public in nonemergency situations. Also, the best kind of tragedy is the one that never happens. By performing these community programs, we can help to prevent fires, wrecks, and so on from happening.

- The mission hasn’t changed in the history of the fire service; it’s to protect others. CRR does that in the right way. It puts us back in neighborhoods, dealing with the people we protect.

As I see it, CRR is an untapped prescription for treating our growing suicide epidemic among first responders. Remember Miss Smith? How many incidents have we responded to that would have had improved outcomes if only we were able to identify the link that CRR could have resolved? We do not know how many injuries were prevented and lives saved through proactive CRR programs, but we know how awesome we feel when we make a “save.”

Consider the impact on first responders’ mental health if we tracked and celebrated the reduction in injuries and deaths that resulted from focused CRR interventions. We need to fund a scientific study on the correlation of CRR and first responder mental health. CRR provides the satisfaction from our helping others and making a difference, After all, isn’t that “why” most of us became first responders?

References

1. Dill, Jeff. Personal interview. 4 April 2018. Firefighter Health Behavior Alliance. 2016. www.ffbha.org/.

2. Sinek, Simon. “Start with why—how great leaders inspire action.” TEDxPugetSound, 28, Sept. 2009, youtu.be/u4ZoJKF_VuA.

3. Sullivan, Andrew. “The Poison We Pick,” New York Magazine, Medium, 19 Feb. 2018. medium.com/new-york-magazine/the-poison-we-pick-261d062e6938.

DAVID BRASELLS is a 17-year veteran of the fire service assigned to Special Operations Truck Company 21 in the Nashville (TN) Fire Department. He is an adjunct instructor for the National Fire Academy, where he focuses on community risk reduction. He has served as president of the Middle Tennessee Fraternal Order of Leatherheads Society (F.O.O.L.S.) for the past five years. Previously, he was a photojournalist and a producer in television news for 22 years. He has a bachelor’s degree in radio and television production and a popular YouTube channel Instructor 5 Productions.