Compartmentation vs. Sprinklers— N.Y. High-Rise Fire Rekindles Debate

features

Regional Executive Coordinator Northeastern States National Automatic Sprinkler & Fire Control Assn., Inc.

“There were no new lessons learned. The fire (in the Westvaco Building) behaved exactly as we predicted a fire in a curtain wall building would behave after our investigation of the One New York Plaza fire. In fact it’s a replay of One New York Plaza.”

This was the reaction of former New York City Fire Commissioner John T. O’Hagan to New York’s latest high-rise fire in a 44-story office tower at 299 Park Ave. in midtown Manhattan. O’Hagan, who is considered to be the prime mover behind New York’s famous high-rise fire safety law, known at Local Law 5, was alluding in his statement to a fire on Aug. 5, 1970, at One New York Plaza, in New York’s financial district.

That fire and a similar fire four months later at 919 Third Ave. stirred civic concern about the safety of the two million people who use New York’s office buildings daily and ultimately led to the enactment of Local Law 5. The two fires left five people dead, 100 injured and $12.5 million property damage.

Last June 23, a five-alarm fire in the Westvaco Building raged out of control for nearly three hours, trapped 16 people on upper floors, depleted most of Manhattan’s on-duty fire fighters and apparatus, and reopened in a dramatic way the dormant controversy as to the best form of protection for high-rise buildings in New York: compartmentation or automatic sprinklers. A principal reason for reviving the controversy was the fact that when the fire was over, 127 fire fighters were injured—17 of them seriously enough to require hospitalization. This fact in itself prompted speculation that high-rise fires in compartmented buildings always lead to large numbers of fire fighters being injured with the possible consequence of long-term disability pension obligations for a city already deep in financial trouble.

Because, as noted by former Commissioner O’Hagan, the fire bore such striking similarities to the one 10 years earlier that had led to Local Law 5, it is again appropriate to look into the type of fire protection that a compartmentation option offers and to identify those deficiencies in this kind of passive building protection that contributes to large fire losses such as One New York Plaza, 919 Third Ave. and now the Westvaco Building.

The Westvaco Building, completed in 1967, is a glass-faced, curtain wall building, 150 X 160 feet, with a centercore design. It covers the block from 48th to 49th Sts. and extends back toward Lexington Ave. It comes within the purview of New York’s high-rise fire safety law, Local Law 5. It had met deadlines for filing compliance plans with that law and has, in fact, chosen the compartmentation option under the law and has proceeded to implement it. At the time of the fire, there was no automatic sprinkler system (nor was one planned). The fire started in a 7500-square-foot compartmented space, the largest allowable in an unsprinklered building under Local Law 5. Had the building owners chosen the sprinkler option, they could have had compartments as large as 15,000 square feet under the law.

Fire fed by paper

Although the fire is still under investigation by the fire marshal’s office at the time this article is being written, the following circumstances of the fire have been confirmed and released to the media:

The first alarm was received by the fire department at 7:38 p.m. Monday, June 24. By 8:10 p.m., it had grown to five alarms. It was not declared under control until 10:20 p.m., nearly three hours after the first alarm had been received. According to fire department sources, the fire started in a computer printout storage area in the 20th floor offices of the Bank of America, located in the northeast corner of the floor. The cause of the fire is believed to be a discarded cigarette. Fire officials believe that the fire started about 5 p.m. and was fed by hundreds of pounds of paper and other office materials before it was discovered by a cleaning woman about 7:30 p.m.

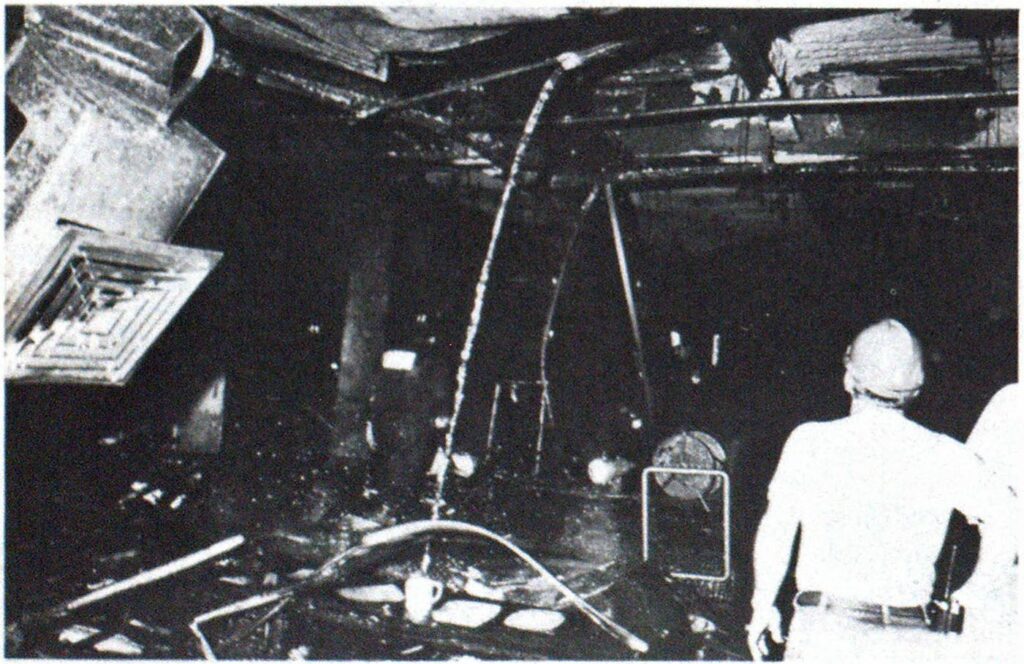

By the time first fire companies got to the building, the intense heat generated by the fire had melted aluminum furniture and warped steel beams, causing the floor slab to crack. The fire gases built up enough pressure to blow out several thick glass windows as the fire fighters were arriving, thus jeopardizing the safety of passersby on the sidewalks below.

Wide World photos

Manhattan Borough Commander Deputy Chief John Fogarty and his men mounted an aggressive interior attack on the fire and many fire experts say that the damage would have been far more extensive but for the determined effort of New York fire fighters. By the time the fire had been brought under control, it had taken the services of 55 fire companies.

High-rise fire problems

Although the fire was confined to the 7500-square-foot compartment, smoke banked down to the 17th floor and rose inside to the 23rd floor. Thick smoke columns billowed up the exterior of the building to the 35th floor.

It has come to be accepted that a high-rise building is determined to be one with floors beyond the reach of fire department aerial equipment. O’Hagan and others who are conversant with high-fire fires have identified various building design deficiencies as contributing factors in the large losses that take place when high-rise fires occur.

Fire fighters work under great handicaps on the upper floors of high-rises. Their only access to attack a fire is by stairways, usually fairly close together in curtain-wall buildings that use side, or center-core designs to maximize leasable space. Because fire-resistive compartments act like furnaces during a fire, heat is one of the worst problems faced. Thus, large numbers of fire fighters are required to fight fires in unsprinklered, compartmented buildings because the severe heat allows them to mount an attack for only five or six minutes before they have to be relieved. In the Westvaco Building fire, the compartment may have halted horizontal spread of fire, but it did nothing to contain the smoke.

Smoke banks down

Because the fire occurred on a hot day and because the interior of the building was cool from the air conditioning system, the smoke banked down to the 17th floor, thereby making it necessary for fire fighters to use the 16th floor as the staging area to mount their attack. This meant that fire fighters had to walk up four flights of stairs to the fire floor with their heavy turnout gear and selfcontained breathing apparatus. Again, this taxed the stamina of the fire fighters and used up precious air before they ever got to the fire floor. It also made the fire labor-intensive from a fire fighting standpoint. The fact that the fire was fought under these conditions is a tribute to the individual dedication of New York fire fighters to their chosen profession.

An automatic sprinkler system would have obviated the excruciating physical demands on the firemen. In fact, in a statement the day after the fire, Chief of Department Francis Cruthers told Vincent Lee of the New York Daily News that the absence of a sprinkler system was crucial.

“There’s no doubt about it,” said Cruthers. “With the system, the fire might have extinguished itself. It definitely would have confined the fire and we would have been able to put the finishing touches on it.”

Sprinkler experience

Apropos of Cruthers’ comments is a study of fires in high-rise buildings in New York City made by Bob Powers, formerly of the New York Board of Fire Underwriters and an authority on high-rise fires. Powers studied 254 fires in high-rises in New York from 1969 to 1979. He noted that of the 254 fires studied, automatic sprinklers put out 251. He further pointed out that in 96 percent of the 251 fires extinguished or controlled by sprinklers, only one to five sprinkler heads opened. More significantly, 80 percent of those 251 fires were extinguished by the sprinkler system without the aid of hose streams. In only 10 percent of the fires was the use of hose streams necessary to support the efforts of the sprinkler system. Powers’ study presents a powerful argument as to why high-rise buildings should be equipped with automatic sprinklers.

During the eight months that it took the Mayor’s Advisory Committee on High-Rise Fire Safety to write what would become Local Law 5, the theory of compartmentation and its area of refuge concept were argued back and forth. The New York Fire Department, represented by then Chief of Department John T. O’Hagan and Deputy Chief Sidney Ifshin of the Bureau of Fire Prevention, wanted the maximum size of the compartment limited to 5000 square feet. They knew empirically from many years of fire fighting experience in New York City that compartments larger than 5000 square feet present great problems to fire fighters and they deemed that compartments larger than 5000 square feet could not be manually fought without exacting some toll in terms of fire fighter injuries and extension of the fire.

Because the blue ribbon committee represented the diverse interests that would be impacted by any new law—the real estate industry, large utilities and building organizations—a compromise of 7500 square feet was reached. Because it was now a compromise, this figure represented no expert point of view. It merely allowed for greater flexibility of floor use and could be viewed as a commercial concession to building owners.

Others copy law

No one could have known then that the rest of America was watching and that shortly after the passage of Local Law 5, communities throughout the country would start to adopt the 7500-square-foot compartment only because they lifted it out of Local Law 5 along with other high-rise fire requirements.

Thus, we have seen a proliferation of 7500-square-foot requirements across the country that have no empirical basis and pose to fire fighters in those jurisdictions the same problems they continue to present to New York fire fighters. If we could think of any rallying cry after the Westvaco fire, it should be: “Down with the 7500-square-foot compartment.”

The stated reasons for compartmentation are several. Compartments are designed to limit the spread of fire and smoke, to provide the fire department with a staging area from which to mount an attack on a fire, and to provide people on the fire floor with a horizontal exit to an area of refuge, where they can remain safely until rescued by the fire fighters.

Local Law 5 says that these compartments in existing buildings may utilize present partitions if they are of one-hour fire resistance. New construction, however, must use two-hour fire-rated partitions for compartments. If modifications are made in existing buildings, those one-hour fire-rated partitions must be brought up to twohour partitions. The law also provides that each area of refuge must be protected by a fire door with self-closing hardware and that each compartment must be able to accommodate all the occupants of the other compartment, with each refugee assured of a minimum of 3 square feet in the area of refuge. People in the real world find the refuge requirements more idealistic than practical, especially in multi-tenant buildings.

Compartmentation weaknesses

Compartmentation works within certain limits that must be recognized by risk managers and other decision makers. The most obvious flaws are the poke-throughs that occur which are not properly fire-protected and cannot be monitored by public inspection agencies, such as the building and fire departments.

The self-closing door hardware is seldom properly maintained. Doors become beat-up with use, and closers frequently cannot exert enough force to make a positive closing. Since the poke-through and improperly maintained fire doors are real problems, the compartmentation protection is seriously compromised.

The compartmentation also does little—as One New York Plaza and the Westvaco Building showed us—to prevent the vertical movement of smoke in a building by way of elevator shafts, duct work and pipe chases. In the case of the curtain wall building, smoke and heat can be transmitted by way of the skin opening, which is the space between the concrete floor slab and the curtain wall’s inner surface. This space is more frequently called the “flue space.” In the 130 years that Factory Mutual Systems have been keeping loss records, they have found that 72 percent of their losses could be accounted for through the human element. Poke-throughs and improperly maintained door hardware are good examples of this.

Certainly another drawback of compartmentation is delayed discovery of the fire. In the case of the Westvaco Building, the fire is estimated to have had over two hours to grow before it was discovered by a cleaning woman. Under Local Law 5, sprinkler systems must be equipped with water flow alarms connected to a central signaling station. Had the Westvaco Building been so equipped, an alarm would have been sent to the fire department as soon as water started to flow in the sprinkler piping.

Little has been said about the changing nature of office buildings. Combustible loading today is probably much higher than it was 10 years ago in One New York Plaza. The increase in the use of plastics with twice the fuel content of cellulosic materials and the introduction of other non-office type occupancies, such as boutiques, clothing apparel shops and public assembly occupancies has really changed the fire problem in high-rise buildings.

Effect of tenancy

Local Law 5 and similar laws do not address the problems posed by the multi-tenant, speculative building versus the single-tenant building, best explained as those buildings housing corporate headquarters or other large enterprises that occupy the building exclusively.

It has been recognized by authorities on fire, but not by the law itself, that the single-tenant building is inherently safer because of centralized control over building operations, a concern for the corporate image and safety of employees, and a tendency for the single tenant to be more alert to liability problems. In a single-tenant building, the tenant pays insurance premiums on the contents and the building. Almost everyone agrees that the single-tenant highrise is usually better maintained from a fire safety standpoint and the tenant invariably chooses to comply with Local Law 5 by way of the automatic sprinkler option. Since the building code permits sprinkler systems to be taken off the existing standpipe system in an office building, costs tend to be reasonable and competitive with fire-rated compartmentation.

The multi-tenant building (such as the Westvaco Building) is another story. The presence of several hundred tenants in a building poses fire safety problems that the single-tenant building does not know. These include illegal alterations affecting the fire resistance of compartment walls, introduction of hazards that other tenants may not be aware of, and higher combustible loading—depending on the nature of the tenant’s business. Because the multi-tenant building is inherently more dangerous than the single-tenant building, serious thought should be given to mandating automatic sprinklers since there is no possible way that the building and fire departments can police changing use in the present booming office building market.

Fire economics

Almost universally, the subject of fire economics is either misunderstood or not properly appreciated. Reliable sources have told us that 4000 man days were lost in the days immediately following the Westvaco Building fire. Taking a conservative average daily wage of $50 per day, this lost time alone amounts to $200,000 in lost wages. The hospitalization and treatment cost for the 127 injured fire fighters has not yet been calculated, but it could be enormous since a fire fighter’s injuries go on his record and can later constitute grounds for a disability pension. The ripple effect that spreads from the area of a fire—right down to the corner pretzel vendor—can be economically staggering to the immediate community. The business interruption losses suffered by the tenants can run into the millions. We shouldn’t forget that the direct losses resulting from the fires at One New York Plaza and 919 Third Ave. amounted to $12.5 million in 1970 dollars.

An interesting lesson in fire economics is a major insurance carrier’s “maximum foreseeable loss” (MFL) formula. This formula is an estimate of what the worst possible catastrophic occurrence could be at any given location. It is an approximation based on an individual underwriter and engineer’s best estimate. In high-rise buildings, two to six floors constitute a maximum foreseeable loss area.

The worst possible event, of course, is a fire. Using a 40,000-square-foot building in New York City at a cost per square foot of $60 for repair and replacement, the MFL would be $14 million for the six exposed floors. This is, the reader must recognize, a rough estimate to be used as a guidepost to maximum losses in a high-rise fire.

The maximum foreseeable loss formula would be applied to a high-rise office building in New York City.

Using the same concept as MFL, a similar formula, called “most probable loss,” can be applied to a fully sprinklered building in New York City. It would show that the most probable loss would be in the vicinity of $100,000. These formulas were developed after a great deal of research into high-rise fires.

As fire economics become better understood, we may find the pretzel vendor suing the building owner who fails to take adequate steps to prevent economic injury to his neighbors.

As former Commissioner John T. O’Hagan said, “There were no new lessons learned from this fire.” They had all been learned 10 years previously. It will be 1987 before every high-rise office building in New York will be in compliance with Local Law 5—we hope. One of the interesting facts to emerge from this fire was that the owners of more than 300 high-rise office buildings have so far failed to meet the legal deadline last June 13 for the filing of plans showing how they would comply with provisions of Local Law 5.

August 5, 1980, was the 10th anniversary of the deaths of security guards Richard Little, the father of two children, and Salvador Martinez. Little was making his rounds when he discovered the fire at One New York Plaza on that hot August day just before 6 p.m. He ran one flight down to the 32nd floor, alerted other guards, and then he and Salvador Martinez pulled their jackets over their heads and headed into an elevator. They never made it out of that car. Both were found dead there by fire fighters—the first victims of fire in a modern Manhattan skyscraper. Four months later, they were joined in death by three other victims of a high-rise fire at 919 Third Ave.