BY KATHI OSMONSON, DON PORTH, AND JERROD BROWN

Often, when a police officer is called to a youth-set fire, it is after the fire has been extinguished. The officer may see no need to involve the fire department or to refer the case to the county attorney’s office since no serious damage has occurred. Parents or caregivers may not understand the gravity of this behavior, may not want to get their child in trouble, or may not want to make themselves look bad. They may think that a small fire is not very serious or that firesetting is just a phase that every child goes through. This is a concern because any fire may result in economic losses, destruction, injuries, and death.1

According to the Juvenile Offenders and Victims: 2014 National Report by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), 40 percent of individuals arrested for arson are under the age of 18, and 58 percent involve youth under the age of 15. Most states also have an age of accountability; often, children under the age of 10 will not be charged with arson.2

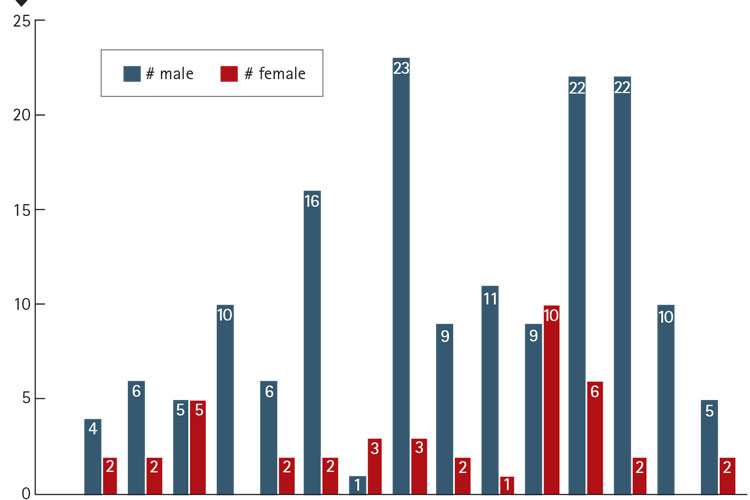

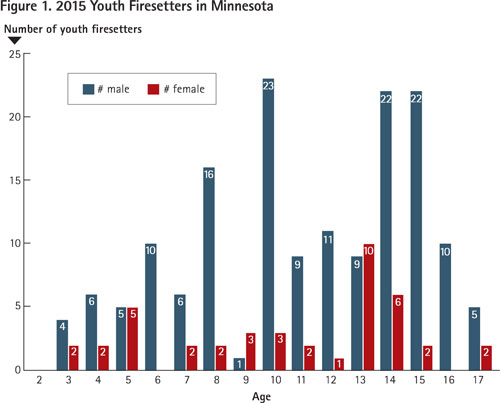

Research estimates there are between 250,000 to 500,000 acts of arson per year, which accounts for 25 percent of all fires in the United States.3 The majority of youth who misuse fire are males who become involved with fire between the ages of five and 10, which is a period characterized by cognitive development. (1) 4 Note that the five- to 10-year-old age group is typically not represented in the arson arrest data because of ages of accountability.

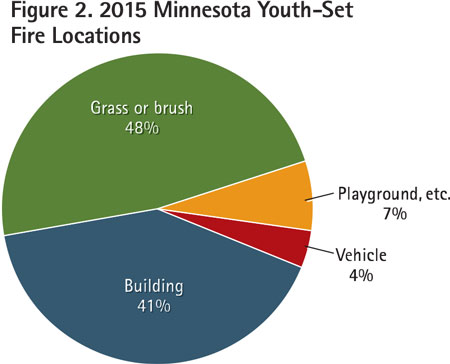

Figures 1 and 2 offer preliminary data for 2015 on the age and gender of youth firesetters in Minnesota and a breakdown of where certain fires were set. Note that in Figure 1, there were an additional 185 incidents for which no age or gender is given.

Influencing Factors

Many factors influence firesetting behavior onset, frequency, and severity. First, age is sometimes a prognostic indicator and may be used as a starting point for ruling motivations in or out. Typically, curiosity might drive the use of fire in younger children, but delinquency typically does in older children. Cries for help or psychological disorders (cognitive or emotional deficits) can present at any age. Motives such as curiosity, control, or anger can impact the severity of the firesetting incident, which is evident in the person’s history of firesetting and recidivism. (4) Some studies suggest children model fire-related behaviors from adults igniting camp fires, cigarettes, candles, and fireplaces. Youth firesetting is not always simply about curiosity or imitating adult behavior; it may be a direct expression of aggression or an attempt to gain control over a negative life event or other situation. (3, 4) Thus, the complexity of youth firesetting indicates that children typically display a range of behavioral issues cumulatively contributing to deliberately setting fires. (4)

|

| In 2015, 386 youth-set fires were reported in Minnesota, of which 185 listed neither age nor gender. “Age as a factor” listed 103 cases and “playing with ignition source” listed 131 cases. Forty cases were listed as under both ”playing with ignition source” and “age as a factor.” The youth fire intervention module revealed another 54 cases, and a search of the narrative reports yielded an additional 138 cases. Many of the cases found in the narratives did not list an ignition or a human factor. Of those that did list ignition factors, “misuse of materials” and “undetermined” were most prevalent. The ”undetermined” narratives stated that youth misusing fire could not be ruled out, and the situations were indicative of youth-set fires. (Source: Minnesota State Fire Marshal Division.) |

Although some juveniles involved in firesetting incidents may purposefully disregard the law, a substantial proportion of these offenses could be unintentional-a youth may simply not know any better. Although most children and often adults do not comprehend the innate dangers and criminal aspects of firesetting, youth with intellectual disabilities, cognitive or emotional impairments, and brain-based injuries may have greater difficulty. As such, fire service professionals must consider that youth who display firesetting behaviors may not understand the potential damage or injuries that their playing with fire might cause.5

Why Don’t Kids Know Better?

The dangers of fire are not obvious to most adults and children. Many adults have misconceptions about fire, since we do not use fire every day as much as in the past, when open flames were used to burn garbage, to cook, or to heat homes. The media irresponsibly misrepresent and even glorify fire. News media reporting fires often show video clips of raging fires, usually with no fire prevention message attached. Television, movies, advertising, and social media are full of incorrect information and the glorification of fire.

The common use of fire in our modern lives (birthday candles, gas stoves, fireplaces, and camp fires) can lead to the assumption that children who exhibit general common sense based on lessons they have been taught and absorbed-for example, don’t play in traffic or don’t ingest toxic substances-will inherently understand the danger of fire and avoid firesetting behaviors. Adults may believe that a youth should know better than to play with fire because the youth does not require constant supervision. Such assumptions are perilous, since most adults don’t understand the power of fire. Unless adults attend a course in fire science or firefighting, they will likely get their information from the irresponsible media previously mentioned. Human beings, in general, tend to assume “it won’t happen to me” when it comes to fire prevention and safety messages as well.

You can’t expect children to understand the consequences of fire when they do not understand fire science. The consequences of firesetting are not apparent to youth or adults for that matter. Unlike many of the lessons repeatedly taught during childhood and adolescence-don’t put unsafe objects in your mouth and look both ways before crossing the street-fire prevention involves fire, which is a complex chemical process that is not widely understood. Fire prevention is not commonly explained in detail at school or in the home. Firefighters may visit schools and show fire equipment but may rarely present an obvious fire prevention message.

Fire is certainly not explained every day during a typical childhood. In fact, youth learn about fire mostly through the examples demonstrated by parents, caregivers, peers, or the media. As such, youth firesetting behaviors often mirror the behaviors of these role models. (3, 4) This can be problematic because parents and caregivers often make fire seem harmless or fun or include it in family events such as birthdays, holidays, and camping. In some instances, adults will even assign a fire-related responsibility to a child under the guise of teaching him how to use fire responsibly. These are formative experiences for a child that may lead him to believe that he is capable of controlling fire in general.

Although the damage from even a small fire is relatively predictable for someone who understands fire science, most people do not possess this level of understanding. As such, predicting the spread or speed of a fire is difficult. Children have a limited range of experience and a high likelihood of exposure to incorrect examples of fire use. Children may not experience any negative consequences from using or misusing fire. For example, if a child had previously ignited small fires and successfully controlled and extinguished them without negative consequences, he may falsely predict that his use of fire will never have negative consequences. His expectation that he can predict and control the consequences of his firesetting actions is inherently dangerous.

Potential Intellectual Disabilities

Not all children who start fires suffer from intellectual disabilities. However, children may experience many intellectual disabilities these days. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms include impulsivity and a short attention span. Other deficits may occur along with ADHD. Many children are now diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). These children and adults also have attention deficiencies and may fixate on certain behaviors such as firesetting. It may be difficult for an individual with ASD to maintain eye contact with another person.

|

| The chart indicates only locations listed under “age as a factor” and “playing with the heat source” categories. (Source: Minnesota State Fire Marshal Division.) |

Fetal alcohol syndrome disorder (FASD) may also play a part in a child’s behavior. Kids with FASD are highly suggestible and may be more at risk for repeating behavior that they see in the media. Individuals with FASD also like to please people, especially authority figures. A fire investigator may get false confessions from people suffering from FASD because they want to make the authority figure happy.

Difficulty in detecting and comprehending safety messages may be amplified when a youth has a psychological disability. Youth with psychological disabilities may be even more susceptible to adult examples and influences, even as they grow older. Problems can arise because physical development makes it easier for youth to find or obtain matches and lighters. Physical development (e.g., motor skills) of youth with intellectual disabilities allows them to manipulate matches and lighters without necessarily understanding the potential danger (e.g., heat of the flame, ignition capability, and how long discarded cigarettes or fireworks remain hot enough to cause a major fire). In some cases, caregivers may believe the example they set carries less importance and is less influential to an adolescent than a child. In reality, what children and adolescents learn, believe, and do is most influenced by the example set by those around them. There is no stronger message than example. To change the behavior in the youth, a modified behavior in the adults around them is necessary.

Fire Prevention Education: How Effective?

Proper education or training can lead to safer behaviors, better predictive ability in youth, and better awareness in adults. Even when instructed in fire prevention or fire safety, children may not understand and retain this information unless it is taught in a developmentally sensitive manner. This learning process involved is similar to those involving complex concepts such as mathematics, which must be taught over an extended time at a developmentally appropriate rate. Nonetheless, most youth have the capacity to fully understand fire safety behaviors if they are taught appropriately.

Competent educators should teach fire and life safety that is tailored to the individual needs of a child. For example, a child or an adolescent with intellectual disabilities may learn at a different pace or through different methods than peers without intellectual disabilities. Although intellectual disabilities do not prohibit a youth from learning about or modifying behaviors, fire prevention and fire safety messages must be tailored to the individual child. Design messages in light of each child’s intellectual capabilities, predictive ability, and exposure to fire. Such messages can include leaving fire tools alone. In fact, some cities have adopted ignition device ordinances making it illegal for anyone under 18 to possess fire-making tools (Mounds View and Blaine, Minnesota, for example). These ordinances mandate that children caught with fire tools attend a youth fire intervention program, available worldwide. The Youth Firesetting Information Repository and Evaluation System (YFIRES) Web site is a helpful resource.6

A youth’s physical size can sometimes lead adults to believe that he is more capable than his intellectual development allows. The brains of youth with intellectual, cognitive, or emotional disabilities develop but at a different rate than their peers. This can result in intellectual capabilities that are out of sync with chronological age. For example, a 14-year-old with an intellectual disability may present as a person nearing adulthood but may function as a child.

It is alarming to note that, nationally, more than 40 percent of people arrested for arson are under the age of 18. (2) However, this statistic may not solely represent malicious or delinquent incidents. A youth with intellectual disabilities may start fires without understanding the potential impact of his actions.

Incarceration is not always the answer. Youth fire intervention specialists can use appropriate measures and assessment tools to determine the youth’s understanding of what he has done and the risk of that person repeating the offense. The youth firesetter may have no concept that an entire building could be destroyed or the lives in it could be lost. In this way, a youth-set fire may be intentional, yet the result may be unintentional. This understanding, combined with referrals to youth fire intervention programs, will result in appropriate interventions to stop the dangerous behavior. Youth who set fires could be incarcerated or attend a youth fire intervention program, which sometimes includes a mental health component. Go to the YFIRES Web site (www.yfires.com) or contact your state fire marshal for more information.

References

1. Johnson, R, Beckenbach, H, Kilbourne, S. (2013). “Forensic psychological public safety risk assessment integrated with culturally responsive treatment for juvenile fire setters: DSM-5 implications.” Journal of Criminal Psychology 3(1), 49-64. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2015). http://bit.ly/29AcKub.

2. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2015). Juvenile Offenders and Victims: 2014 National Report. National Center for Juvenile Justice. http://www.ncjj.org/nr2014.

3. Horley, J, Bowlby, D. (2010). “Theory, research, and intervention with arsonists.” Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16, 241-249. http://bit.ly/29A0nwx.

4. Walsh, DP, Lambie, I. (2013). “If he had 40 cents he’d buy matches instead of lollies: motivational factors in a sample of New Zealand adolescent firesetters.” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 57, 71-91. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21948248.

5. National Fire Academy (2013). Youth Firesetting Prevention & Intervention. Emmitsburg, MD: National Fire Academy.

6. The Youth Firesetting Information Repository and Evaluation System (YFIRES) Web site: www.yfires.com.

KATHI OSMONSON is Minnesota’s deputy state fire marshal, coordinates the Minnesota Youth Fire Intervention Team, and has specialized in fire prevention education and youth firesetting intervention since 1990.

DON PORTH is a consultant on fire and life safety issues, has served on the executive team of the Youth Firesetting Information Repository and Evaluation System, and served 27 years with Portland (OR) Fire & Rescue as a public education officer specializing in youth firesetting behaviors and interventions.

JERROD BROWN, MA, MS, is the treatment director for Pathways Counseling Center, Inc.; is certified as a youth firesetter prevention/intervention specialist; and serves as Minnesota’s mental health consult for youth firesetting.

Fire Engineering Archives