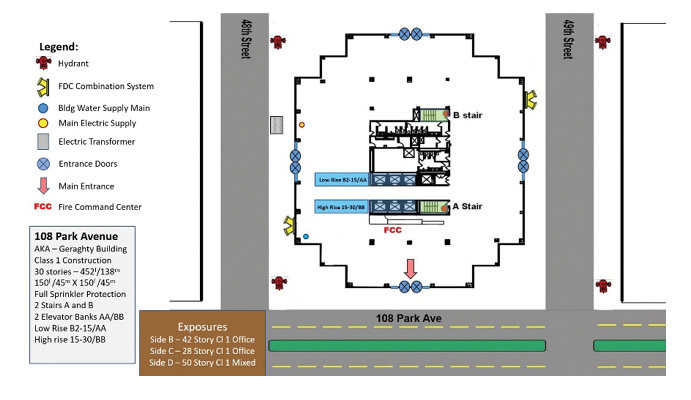

If you were to read the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Firefighter Fatality Investigation reports of firefighter line-of-duty deaths (Figure 1), you would note that these reports often cite the need for preincident planning for all buildings. That realization becomes significantly apparent for tall sophisticated high-rise buildings. The preincident plans will include all of the pertinent details of a high-rise building—its characteristics; construction type; dimensions; and floor plans with stair shafts, elevator banks, and fire protection systems. All of these data are considered “building intelligence” (BI). In a high-rise building environment, the need for preincident planning and BI is more profound because of the structures’ complexity in design, building systems, and divergent floor layouts.

The NIOSH reports also recommend that a dispatch center broadcast available building information while the crews are responding. These announcements will trigger firefighter awareness and familiarization with the building and provide details of any potential firefighter threats within the structure. The local fire department would obtain this information from visits made to specifically gather BI on the details of the structure’s construction, characteristics, fire protection systems, renovation history, abatement issues, and deconstruction. The BI would also include floor diagrams of where the battle with fire will take place.

RELATED

High-Rise Codes and Fire Loads: A Compromise in Trust

High-Rise Building Fires: What’s the Challenge?

The Evolution of Building Intelligence

The concept of BI is not new. In the 1960s, the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) instituted a program to identify and gather information on buildings and complexes considered “target hazards.” This program evolved into prefire planning that may have included evacuation plans. The methods and systems for storing and retrieving the BI collected were rudimentary in accordance with the technology available at the time.

Figure 1. NIOSH Report 37, 2007: Excerpts

Source: Jerry Tracy.

The BI was written down, organized, made into drawings or illustrations, put in binders, and kept in the chief’s vehicle, the first-due unit, or a local firehouse office. If a fire was significant and beyond routine, the binders would be retrieved and reviewed in a hard copy format. That was about all that could be done given the technology of the time.

In the mid-1970s, there was an attempt to digitize the information and store it on microfiche, clear film that could be read on the microfiche reader—the digital device libraries used to store old newspapers and magazine articles. However, the portable reader was difficult to use at the scene of a fire; it was even harder to use when the weather was inclement. In the 1990s, the process was advanced to producing digital prefire plans that provided clear, color-coded graphics of building systems, footprints, and resources.

The Era of High-Rises

You should critique fire operations regularly, not only when there are fatalities. Incident commanders (ICs), field units, and firefighters should customarily review fire operations to assess whether the procedures followed were appropriate for the fire conditions encountered; how the operations were conducted; if there was effective control of fire, smoke, and ventilation; and to review final extinguishment. The review and critique process leads to improved strategies and tactics that are shared verbally and are eventually written into tactical and training bulletins. They become part of training evolutions and are embodied in standard operating procedures (SOPs).

All of these actions make firefighters more efficient and effective, but they tell us little about what to do or what our options are when confronting emergencies in complex high-rise buildings. In these structures, you can expect to encounter nonstandard layouts, machinery spaces where utility main isolation controls are located, and spaces that generate alternative power sources. A multiple-occupancy high-rise will be comprised of varied types of occupancies.

The fire service is beginning to realize that its SOPs may lack information or be obsolete because the methods of attack in these guidelines are no longer applicable to the architectural designs of today’s high-rises or older buildings that have been renovated. These buildings can be large and complex in layout, have unprecedented fire loading and fire dynamics, and were built under a performance-based code or a minimum code or standard. In reality, the typical fuel loading in a high-rise office occupancy will burn with heat release rates exceeding the ASTM/Underwriters Laboratories standards for time and temperature exposure rates. Also, the toxic smoke generated may pose more danger than the fire itself.

The Next Step

The time has come for the fire service to take the next step, beyond gathering information to including firefighting “directions”: Where, how, and who will implement an effective attack, control, and suppress the fire? To engage in battle necessitates understanding and being familiar with the battleground. The significance of having an intimate knowledge of the battleground can be traced back to Chinese general and military strategist Sun Pin, author of Art of War: “A good battle plan is based on a sound ‘knowledge of country.’” This preparedness concept is analogous to the “Art of Building Intelligence,” which entails the fire service’s visiting high-rises and gathering detailed relevant data.

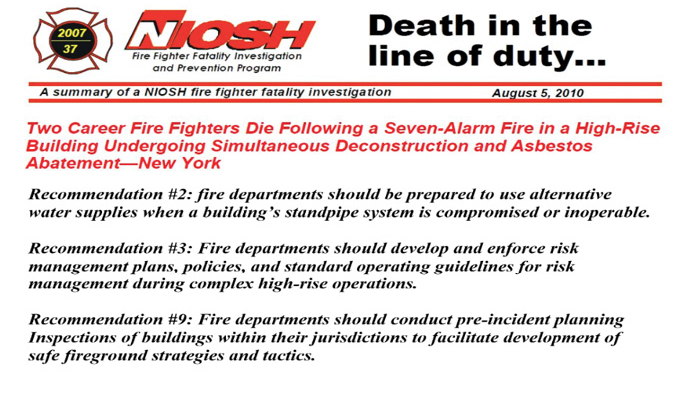

Table 1. QAP-1

Source: Jack J. Murphy.

“Knowledge of the country is to a general what a rifle is to an infantry man and what rules of arithmetic are to a mathematician,” explains Sun Pin. “If you don’t know the country and landscape, you will be subject to making gross mistakes; therefore, study the country and landscape. Use the concept of using the most detailed and exact maps of the country that can be found; they should be taken and examined and re-examined. ‘If it is not in the time of war, the places should be visited.’”

Relating this passage to the “Art of Building Intelligence”: Knowledge of tall buildings is to an IC what a hose is to a firefighter and what SOPs are to fire officers. If you’re not familiar with tall building components and systems, you will be subject to making gross mistakes; therefore, study building construction features and fire protection systems, especially the fire alarm control panels, for smoke management control. Using and reviewing drawings of the building map and footprint at street level and of floor plans will familiarize you with the landscape of the battle operations. Review them annually. You should be familiar with the battleground before the fire/all-hazard (nonfire) incident occurs. Fire units and ICs should visit these tall buildings before the battle begins.

Adopt a “Know Before You Go” Mentality

Gathering high-rise building information facilitates analysis and planning of actions before the incident occurs by providing the IC and firefighters with intimate BI about the structure. The target building information is key to formulating battle plans (BPs) that address alternative strategies and novel tactical approaches that may not be addressed in traditional SOPs. Equally as important to the BP is a “Know Before You Go” (KbyG) mindset that focuses on gathering all the relevant building information from fire companies and distributing intelligence to support high-rise operations as the incident is unfolding.

In your KbyG recon, consider the vertical challenges for a fire attack and all-hazard (nonfire) events related to the building’s external/internal risks for man-made threats (bomb, active shooter, and utility failure, for example) and natural disasters (flooding, earthquake, hurricane, tornado.) Also, be aware that the fire dynamics (fuel load, rapid acceleration travel including smoke, floor layout, and so on) in a high-rise undergoing alterations may also have changed. Learning of a major alteration being proposed for a structure would be justification to conduct a recon visit. This would be in addition to your annual scheduled recon and periodic scheduled risk analysis survey. It is suggested that members of various fire company shifts be scheduled (cycled) to visit the building. A set of fresh eyes may more readily discover a risk or problem overlooked in the previous inspection.

Share What You Learn

The building features of high-rise and future construction designs will continue to challenge the fire service unless we employ the art of BI and share what we learn about the building with the first arriving units and ICs. Some departments present their BI on printed forms/sheets/cards on site or have crews retrieve it in the form of a Quick Access Plan (QAP) from an electronic base using computers/tablets/iPhones. This information, available in three manageable levels, fosters decision-based knowledge instead of an approach based on guesses.

A high-rise building recon produces BI for legacy documents at three manageable QAP levels for quick access and reference on arrival of the first units and the chief officer who will assume command.

QAP-1

Table 1, “QAP-1 Fire Units Initial Operations,” includes safety and precautions, and temporary building considerations for fire protection system impairment and ongoing alteration projects. This essential QAP level, which contains building knowledge that enables the commencing of operations and critical information for covering citywide fire units and mutual-aid groups, is available to the fire companies in the immediate response district. It helps prepare fire units for battle in these vertical cities.

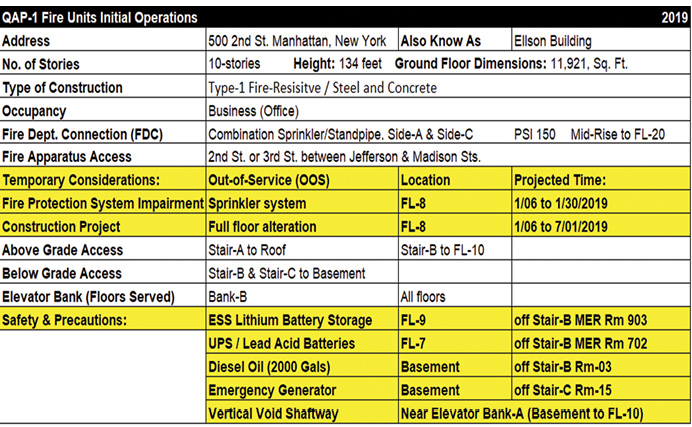

QAP-2A

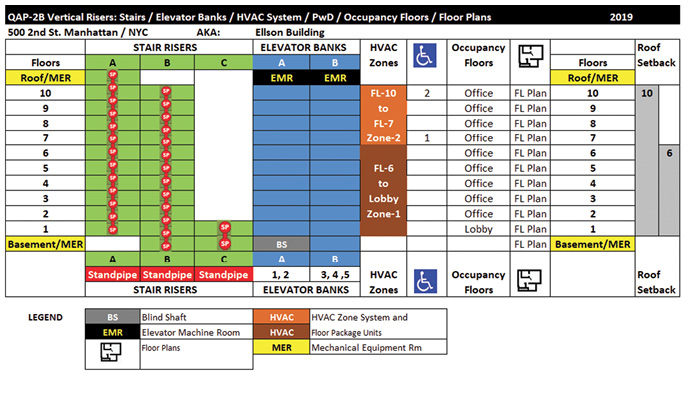

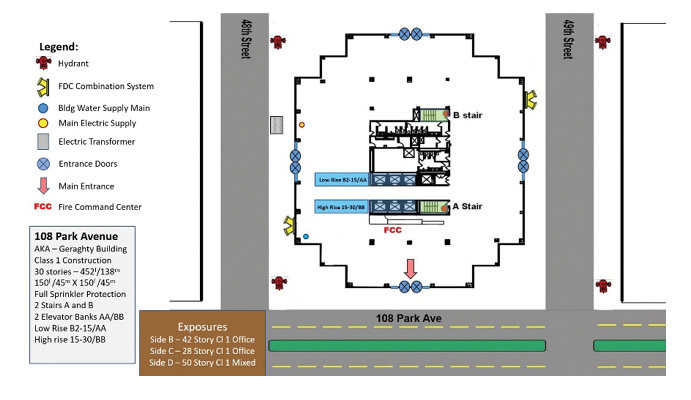

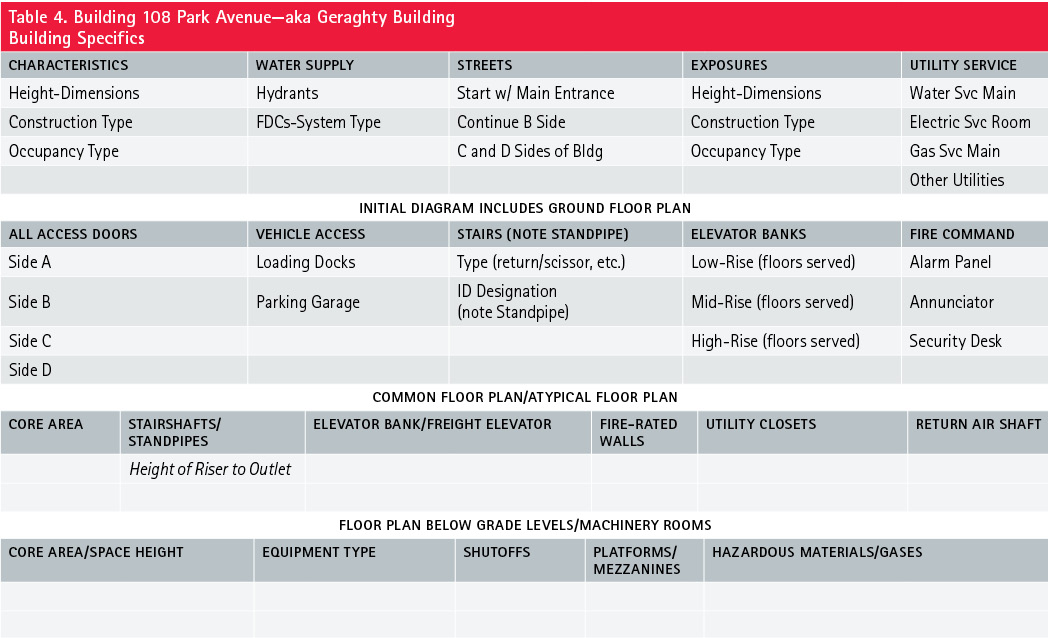

Figure 2, “QAP-2A Building Footprint Map,” presents a street level view, with fire department connections (FDCs), building access, stairwells, and elevator banks for the quick deployment of personnel. Figure 3, “QAP-2B Vertical Risers,” shows the stairs/elevators/heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems; people with disabilities; occupancy floors; and floor plan and roof setback levels to ascertain above- and below-grade stair access points, elevator floors served, HVAC floor zones, and so on. These QAPs can be stored and transmitted as electronic [e-building intelligence including BPs to be received through a vehicle mobile data terminal (MDT)] and read using a standard (open market) or dedicated tablet or digital phone device.

Figure 2. QAP-2A Building Footprint Map

Source: Jack J. Murphy.

Figure 3. QAP-2B Vertical Risers

Source: Jack J. Murphy.

The simple QAP-2A building footprint map in Figure 2 has a red arrow (“You Are Here”) that indicates the main entrance. It will provide the first-due fire officer and IC with KbyG BI relative to what is to the left and right of the main entrance. Responders will be able to determine which stairs have a standpipe riser, those that provide roof and below-grade access; elevator banks; the fire command center, FDC connections, and fire hydrants on Sides A and C; building size-up details (dark brown box); and exposure buildings (gray box). This site map can serve as the basis of a battle plan for a fire attack; it can be read in 30 to 60 seconds, at which time the IC can deploy personnel. The standardized color schemes and icons used for Figures 2 and 3 provide a consistent format for the fire department.

When an emergency response becomes an incident, a Comprehensive Level QAP-3 will provide the IC with more detailed building information that includes an illustration of all floors, tenancy use or machine space, stairs, standpipes, and elevator banks and the floors they serve. Most important is the visual representation of the HVAC zones that will be used to manage and control smoke in coordination with the chief building engineer.

Depending on the time of day, or on weekends, an inexperienced building service employee may be on duty who does not have an intimate knowledge of the HVAC system and its functions for fire and smoke control. The QAPs can provide contact information for the chief engineer with whom you can speak and who may be able to manage and control building HVAC systems remotely with a computer program referred to as a “Building Management System.”

Building Information Card

Soon after the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks, the Fire/Life Safety Directors Association of Greater New York (FLSDA) testified before the New York City (NYC) Council and National Institute of Standards and Technology/World Trade Center Commission (NIST/WTC) relative to life safety needs within high-rise buildings. One of the FLSDA recommendations called for a Building Information Card (BIC) for high-rise buildings. This BIC would detail critical building information for ICs and present specific building knowledge that may be unique from one high-rise structure to another.

In 2002, the FLSDA and FDNY Bureau of Fire Prevention joined forces to enact the first fire department BIC in the United States. Soon thereafter, the city enacted Local Law-26 (2004) requiring that all high-rise office buildings have prepared emergency action plans (EAPs) for all-hazard (nonfire) emergencies. The NIST/WTC Commission report also prompted National Fire Protection Association 1620, Standard for Pre-Incident Planning (2010 edition), as well as the International Code Council’s building and fire codes that were adopted in the model code for states and large municipalities to enact.

Battle Plans

How many times have you said, “I wish I had known about this beforehand” or “I would appreciate some advice on what I should be considering right now”? Both examples indicate a lack of intelligence at the time it is needed on the fireground. BPs improve our evaluation of situations and provide insight into what we can expect, what we can do about it, and other options we may not have considered.

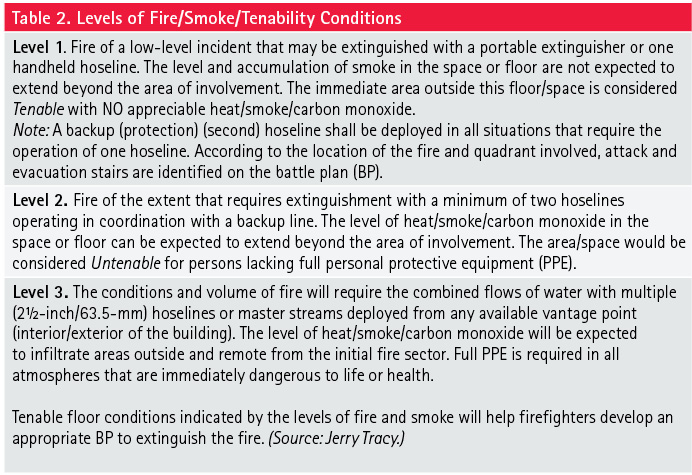

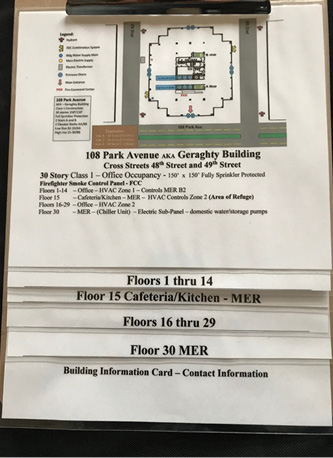

BPs link BI to existing SOPs with the specific details of a particular building. The foundation of these plans can use the BI acquired for the QAPs. They will be enhanced further with diagrams of the building proper with a ground floor map, street access, and neighboring exposure buildings. The BP will be provided on printed pages that are turned up (layers) to reveal additional details and diagrams of floors, atypical spaces, floor layout, access points (stairs), and core area to exterior walls. The intent of battle planning and using diagrams is to expedite the time to implementing appropriate plans of action and tactical decisions and approach for fire extinguishment on specific floors or in spaces. Committing resources and tactics can be determined according to the level of conditions (fire/smoke/tenability) encountered on a floor or space (Table 2).

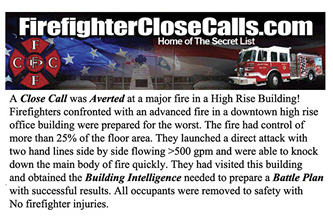

QAPs and existing SOPs may not provide the intimate details of the building, floor, or space to enable making resolute decisions with accurate BI instead of speculation or guesses. Your guess may be an educated one, yet it is not conclusive or rapidly responded to and is often inaccurate or under-predicated. Although we get a lot right, we often must do fancy manipulating to just get by. However, sometimes we don’t just get by. As we often hear, “Sometimes you bite the bear, and sometimes the bear bites you.” BPs are intended to reduce the number of times we get bitten by the bear (Figure 4).

BPs and BI are a leap forward from basic preplans. They provide strategies developed and evaluated by experienced fire personnel and also delineate tactical options at specific buildings/floors/spaces, providing a strong indication of what we should be doing to safely and effectively resolve the problem with which we are confronted. Before it was promulgated, experienced chief officers and fire service leaders scrutinized and accepted them.

Figure 4. A Close Call Averted

Courtesy of FirefighterClose Calls.com. (Graphic by Jerry Tracy.)

BPs for high-rise buildings are guidelines for the units engaged in fire suppression, evacuation, search and rescue, and the measures and resources an IC must satisfy to support the overall operation. They are a step beyond a department’s SOPs that may advocate initial tactics with alternatives but do not delineate attack modes and approaches for fire suppression operations in a particular building, floor, or space.

There may be many floors that have a common arrangement and fuel loading so that one BP can suffice. BPs become most appreciated for the most complex and challenging buildings, floor arrangements, atypical occupancies/spaces including cafeterias or areas such as mechanical equipment rooms, electric service (high-voltage) with vertical voids, and HVAC zones. Consider that some of these atypical spaces may contain contents fabricated with materials that can burn furiously because of their components such as machinery’s titanium parts. Oddities such as this may require adding an extinguishing agent to water from a standpipe.

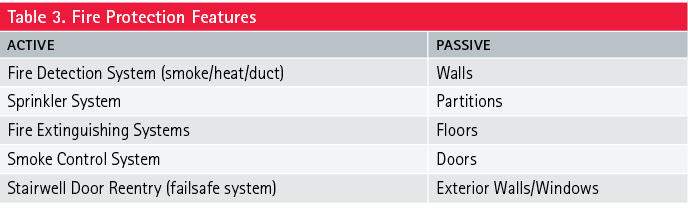

BPs consider the active and passive fire protection features (Table 3) that are reliable, including a smoke management system. BPs offer alternative tactical options of approach to be applied when a single hoseline advance is not feasible or advisable. They are the next step in the evolution of providing information and intelligence to firefighters where and when they need it the most. When active and passive building fire protection features are not functional, alternative tactical options may be considered.

Developing a Battle Plan

As noted, the BP begins with a recon survey by the local fire company. Existing QAPs can be used for the basic intelligence foundation for the BPs. More detailed data and diagrams will have to be added.

Time may not permit field units to complete a building reconnaissance survey that will cover all the relevant BI and diagrams needed for the BPs. Additional visits with other shifts may be needed.

It is recommended that the fire units use a simple form, brochure, or checklist of annotations and details of a building to be assessed and documented for a legacy document or database that can be retrieved electronically. The information collected should include BI and diagrams that provide a rapid review of the characteristics of a building, its arrangement in relation to the core, modes of transportation (stairs/elevators), standpipes, fire walls, utilities, and the locations of the HVAC return air damper and shaft.

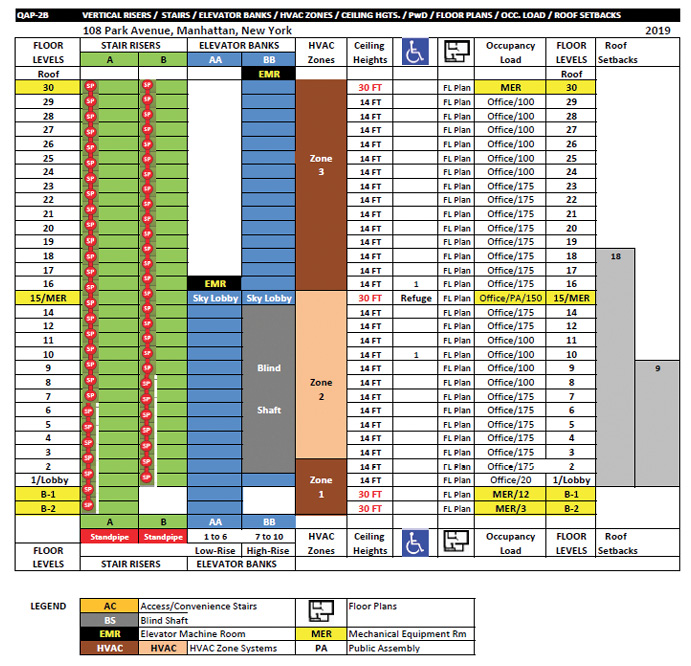

Table 4 lists nonexclusive details to consider when performing an exterior/interior building reconnaissance. Your department may choose to customize a format guide, pamphlet, or checklist of what is to be included in the BP.

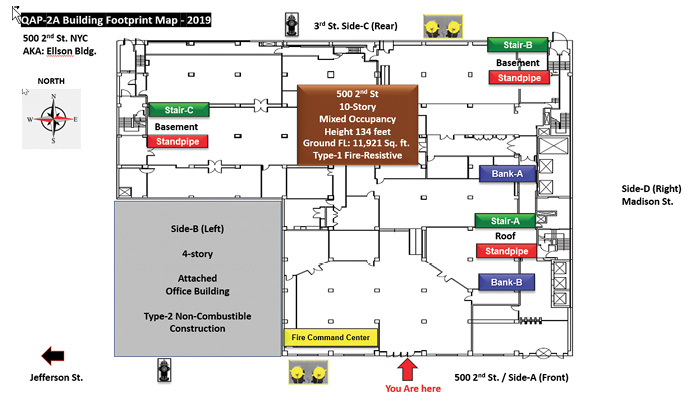

The hard copy of the plan for the ground floor (top page) or initial layer of the electronic access link should begin with a diagram/map of the building footprint at ground level (Figure 5). This principal diagram should exhibit all entrance doors, street access, primary water supply (hydrants), FDCs, and neighboring structures. In addition, identify the location of the utilities—the building’s water main and electric service supply, any electric service (exterior) transformer vaults—the main (with arrow) entrance, the fire command center, and the alarm panel or annunciator.

This primary diagram makes the responding units aware of the characteristics of the area for apparatus/appliance positioning for function and assignment. It also serves as a street map for the IC. This is essential for a street management plan and controlling traffic, apparatus, and vehicles to allow emergency medical services (EMS) units and other agency support vehicles, if required, to arrive and depart and to determine the location of the base staging area for units arriving on the next higher alarms.

Figure 5. Diagram of Building 108 Park Avenue—aka Geraghty Building—Structure, Streets, Hydrants, FDC, and Main Entrance

Graphic by Jerry Tracy.

Advise the local police/traffic department of the street management plan so it can assist with rerouting for traffic flow and control. When confronted with all-hazard emergency (nonfire) events such as bomb, active shooter, and utility failures, other agencies can use these diagrams to implement their plans of action.

The back (flip side) of the primary diagram/page will display the Riser Diagram (Figure 6), which is similar to the QAP-2B. This diagram displays all floors, stairs, standpipes (riser controls), elevator banks, HVAC zones, and machinery rooms. This intel is vital for the IC to manage smoke movement and ventilation for the life safety of the occupants and firefighters operating.

Figure 6. The Riser Diagram (Flip Side of the Primary Diagram)

Source: Jack J. Murphy.

Succeeding pages can illustrate floor plans that are similar (series of floors) from the core to the exterior walls (Figure 7). Separate pages in the layers can depict floors/spaces with atypical layouts such as machinery rooms (Figure 8).

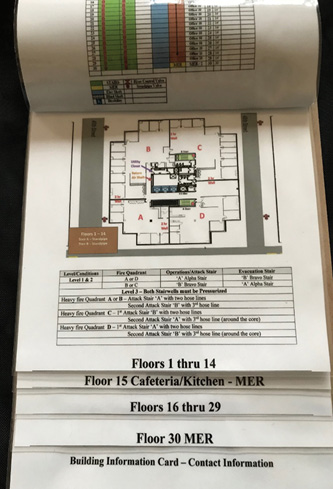

Figure 7. Battle Plans with Top Page Ground Floor and Streets

Source: Jerry Tracy.

Figure 8. Succeeding Pages of Floors and Atypical Spaces Divided into A,B,C,D Sectors

Source: Jerry Tracy.

When Will BPs Be Available?

The interesting thing about BPs is that they will be available once they have been developed, approved, digitally formatted for effective use, stored at the distribution location, and made part of the normal dispatching process.

It takes time to do all that is necessary to get BPs into operation; however, once they are in place and operational, they will be available to any fire or emergency service for as long as they remain in a secured electronic database. That is until something better comes along, such as The Next Step, which begins with an e-building intelligence solution on the structure’s inside components and systems. This solution is a seamless communication “Software as a Service” solution, which, in the future, will be able to be dispatched in a manner similar to the way BPs are. As a situational awareness tool, a SMART e-building intelligence solution card will provide specific building information that will be attained effortlessly and be relevant to firefighter safety in a timely manner.

Note: A special thank you to Chief of Safety Peter McBride, Ottawa Fire Services, Canada, for his consultation and friendship.

Bibliography

Are You Preplanning Your Buildings? Jack J. Murphy, Fire Engineering, Jan. 2009.

Brannigan’s Building Construction for the Fire Service, 5th Edition, Glenn P. Corbett, P.E., ed. Jones and Bartlett, 2013.

e-Building Intelligence Solutions, www.ebisg.com/.

“Enhance Fireground Operations with Digital Building Intelligence,” Jack J. Murphy, Fire Engineering, Jan. 2010.

Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I & II, Chapter 29, Pre-Incident Planning, Glenn Corbett, ed, PennWell, 2009, http://www.pennwellbooks.com/shop-fire-books-videos/firefighter-i-ii/fire-engineerings-handbook-for-firefighter-i-and-ii-2013-update/.

“If These Walls Could Talk: e-Building Intelligence,” Jack J. Murphy, Fire Engineering, Jan. 2018.

International Code Council (ICC) Building and Fire Codes (2012); www.iccsafe.org/.

“Leveraging Building Intelligence for an Initial Response and Beyond,” Jack J. Murphy, Fire Engineering, Jan. 2014.

NFPA 1620, Standard for Pre-Incident Planning (2015 Edition).

NIST Building Tactical Information System for Public Safety Officials/Intelligent Building Response Report (2006).

NIST/WTC Commission Recommendation No.14 Fire Command Center and Building Information Card.

Status of NIST’s Recommendations Following the Federal Building and Fire Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster, Aug 8, 2011; http://wtc.nist.gov/.

Sun Pin, Military Methods of the Art of War. 1999. (R. Sawyer, trans.) Barnes Noble Books, page 62.

“The Call to Gather Pre-Incident Building Intelligence,” Jack J. Murphy, Fire Engineering, Jan. 2009.

Jack J. Murphy, M.A., is chairman of the High-Rise Fire/Life Safety Directors Association, New York City. He is a fire marshal (ret.), a former deputy chief, and a former Bergen County (NJ) deputy fire coordinator. He serves on the following National Fire Protection Association committees: High-Rise Building Safety Advisory and 1620 Pre-Incident Planning, and Building Fire/Life Safety Director. He represents the International Association of Fire Chiefs on the Northeast Region Fire Code Work Group. He is the author of numerous fire service articles and authored a field handbook on the Rapid Incident Command System, authored the “Pre-Incident Planning” chapter of Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II, and co-authored “Bridging the Gap: Fire Safety and Green Buildings.” He is an editorial advisory board member of Fire Engineering and FDIC International. He was the recipient of the 2012 Tom Brennan Lifetime Achievement Award.

Jerry Tracy is a retired battalion chief from the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), where he served for more than 30 years. He began as a firefighter in Engine 90 in the Bronx and Ladder 108 in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. As a lieutenant, he was assigned to Ladder 4 in midtown Manhattan and captain of Tower Ladder 35 on the Upper West Side. He formed and became the first captain of Squad 18, a Special Operations unit and the only squad company in Manhattan. He developed numerous training programs and revised firefighting policy and procedures for the FDNY. He has had published numerous articles in Fire Engineering and WNYF. He was the catalyst to the research conducted by NIST, UL, and NYU Polytechnic Institute on smoke management and fire behavior in high-rise buildings, most specifically wind-driven fires. He was a keynote speaker at FDIC International 2017 and received the Tom Brennan Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016.