Although first responders face potentially volatile situations every day, most have never been taught to spot the warning signs of a potential violent encounter or how to handle this type of situation. According to a National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians study, 52 percent of emergency medical services (EMS) workers surveyed said they have been attacked on the job. In addition, according to the University of Maryland, “The risk of an assault for EMS workers is about 30 times higher than the national average.”1 The Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics reviewed data from 2003 to 2007 to identify common causes of injuries and fatalities in EMS workers; 530 assaults were reported. In addition, there were 59 fatalities during the same study period. Of those fatalities, 8 percent were related to assaults.2 These numbers still do not account for the assaults that did not result in an injury or a fatality.

Inevitably, the number of assaults against first responders is much higher than reported. When conducting training programs to address violence against first responders, one of my first questions is, “Have you ever been assaulted on the job?” Not surprisingly, very few, if any, participants raise their hands. Next, I ask, “What is the definition of assault?” The participants’ answers will generally be very close to the textbook definition of an assault. The term “assault” may be interpreted or used in different ways, depending on the state and local laws.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Responding to Scenes of Violence

Assault: A New Reality for First Responders

Mills: Self Defense for Fire and EMS

However, historically, assault and battery have been crimes that could be committed at the same time. The assault refers to the intentional act that causes someone to be fearful or the threat of immediate harm. Battery refers to the act of offensively and intentionally physically contacting another individual without consent.3 After I provide these two definitions, I ask again, “Who has ever been assaulted on the job?” Not surprisingly, almost everyone in the room will raise their hands.

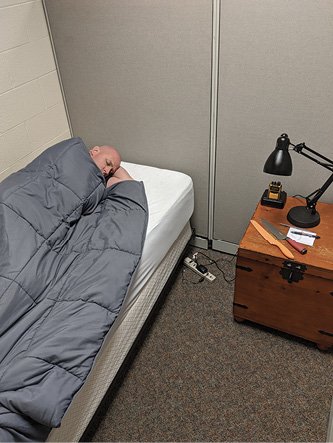

(1) The patient is lying in a bedroom before the first responders arrive on scene. The dispatch information may not be adequate to alert responders; they must maintain situational awareness and identify any potential hazards. Two knives are on the nightstand next to the patient. (Photos by author.)

(2) Having identified the knives, the responder carefully places himself between the patient and the hazard. Always cut off access to any weapons, regardless of the situation.

It is fair to say that the incidence of violence against responders is grossly underreported. Although a few agencies are attempting to capture data on this issue, there will be many challenges. The only possible solution to resolve the lack of data on the EMS side is to create a Violence Reporting tab in the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) to use as a tool to track responders who are verbally or physically assaulted. In addition, required responder training would include tactics for minimizing responders’ exposure to violence, handling situations, and identifying assault so that it can be accurately reported and documented. On the Fire reporting side, the National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS) reports could include a report tab as well.

The Legal Right to Self-Defense

The single most important point for all first responders to realize is that they have the right to protect themselves from injury. They may use self-defense in an environment where they have reason to believe they need to defend themselves against an unlawful use of force and when threatened violence exists. However, the individual threatened has a duty to use all prudent and preventive measures to reduce the chance of the attack. The individual must use no more force than what is reasonably necessary as well. When determining your right to protect yourself, you must consider against whom you are protecting yourself.4 It would be difficult to justify the use of excessive force against an attacker who is much smaller than you.

Another common issue in many self-defense scenarios is the potential for the victims to successfully defend themselves and then become the aggressors. A lack of self-control is not a defense in a lawsuit. Proper training and policies can help minimize the potential of this happening and reduce liability.

The information in this article is for general guidance. Each agency and individual should seek professional legal guidance since the application and impact of laws vary widely according to location.

Department Policy

What does your agency’s policy say? There is a good chance that most agencies don’t have a policy that covers how to respond to hostile situations. Many agencies are adding policies that cover active shooter and active assailant events; however, they don’t help provide guidance for their personnel in most of the incidents that could happen day to day. If you were faced with a hostile situation, would your employer defend you?

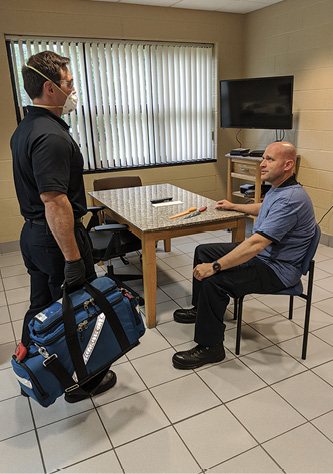

(3) The patient is seated at a kitchen table with a weapon directly in front of him. Before approaching him, responders should consider the type of call and the patient’s state of mind. If the patient is acting aggressively, it is best to defuse the situation and isolate the weapon. If the responder determines that the patient poses little threat, it is still the best practice to isolate any weapons from the patient or anyone else in the area.

(4) If you can’t get the patient away from the weapon, turn the patient’s chair to provide easier access for patient care and to help inhibit access to the hazard. The responder can further restrict access by providing care at the patient’s side.

In January 2011, Walmart fired three employees for grabbing a gun away from a shoplifting suspect and pinning him to the ground until the police arrived. Walmart believed that the employees should have allowed the man to leave the office and should not have wrestled with him. The Utah Supreme Court declared that employers cannot fire employees who fight back when in imminent danger of harm from others.5

In a Pennsylvania court case (Miller v. UCBR, 83 A.3d 484), a claimant was involved in a workplace altercation with a co-worker. The co-worker was responsible for starting the altercation, and the claimant retaliated in self-defense. Many courts have ruled that fighting may be considered a disregard for the standards of behavior that an employer can expect from employees, even when the claimant is not the aggressor in the situation. However, in this case, the court ruled that the use of self-defense was justifiable because the employee took steps to de-escalate and avoid the conflict. The claimant only used self-defense when there was an indication of imminent bodily harm.6 These two cases point out the importance of becoming familiar with hostile incidents that have occurred in your state and the need to teach personnel de-escalation techniques.

One of the biggest concerns should be how your personnel will respond to a violent encounter. If the department or agency does not train responders to the level to which they are expected to respond, how will they respond? It is reasonable to expect responders to fall back on their training. In this case, the department did not train them, so it is likely that they will respond in the way they were personally trained. This can be a significant problem in many cases.

If one of your personnel was trained in mixed martial arts (MMA), the choke hold is one of the primary control techniques. A responder who has never received any training and has never been in any altercation may respond in a manner that causes excessive injuries to the aggressor, or he may flee the situation and leave his partner in a dangerous situation.

Agencies should also be concerned about those who receive training. For example, a martial arts school owner, after seeing a news report of fire/EMS personnel being assaulted, wants to help; he offers free training classes to help the department prepare its personnel. The issue here is that the techniques taught are more applicable to combat situations. The knife defense techniques involve controlling the wrist of the knife-wielding attacker and stabbing the attacker with his own knife before slashing his throat. Are these the techniques we want our responders to learn?

The ARREST Program

To train first responders in handling hostile situations, your program should incorporate the ARREST principles: Awareness and identify, Request assistance (law enforcement), Reduce hostility, Escape the situation, Self-defense, and Treat any injured and document accordingly.

Awareness

The first essential component of any training program for a response to combative persons should be an awareness or preparation phase. Most fire/EMS personnel have received little or no training on how to identify potentially unsafe scene conditions or how to handle them once they have been identified. The training should identify clues for responders, not from the moment the call comes in. Dispatch information can provide some basic clues to a potentially unsafe situation and the need to exercise caution, such as a call involving an assault, a suicide attempt, a domestic dispute, or even an unknown medical situation. In addition, the initial dispatch information may identify potentially hazardous locations, such as a known drug house, a bar, a residence with a history of violence, or even reports from dispatch with conflicting information, which should put responders on alert. Work with your dispatch center and mark these locations to improve emergency crews’ safety.

Another highly debated topic is the practice of staging for suicide attempts. Does your department require you to stage for all suicide attempts? Many agencies require units to stage only for suicides by violent means. What about a suicide attempt by overdosing on pills? I always recommend staging for all suicide attempts as a formal policy. In my agency, a crew responded to a reported suicide by pill overdose. The dispatcher was not aware that the incident was a murder-suicide, and responders unknowingly walked into an unsafe scene because the perpetrator was still on scene and not secured.

Once your crew arrives on scene, maintain situational awareness and continue to assess the scene. You may be responding to a medical incident, but continually assess for suspicious activity, people injured, animal hazards, or something that just does not seem right. Before knocking at the door or entering the building, take 10 seconds to assess hazards. Listen for any sounds of arguing, fighting, or other suspicious behavior. When knocking at the door, stand off to the side and announce your agency (fire/EMS). We are not in the business of surprising people, and we want everyone to know that we are there to help.

As you walk toward the patient, continue to assess your situation and get an overall impression of the patient. While walking through the house, look for exit routes, if needed; weapons, drugs, or alcohol; physical damage to the property (holes in walls, etc.); needles; and any other signs that a hazard may be present.

When you arrive at the patient and come across a weapon, how does your department want you to handle the situation? In the training I have provided, I have heard every answer, including taking the gun and emptying it. There are many variables, depending on the aggressiveness of the patient and family members; however, I would recommend cutting off access to the weapons. If a patient has a firearm on the dresser next to him, carefully positioning a responder providing care between the patient and the weapon is the safest and most effective way to isolate the hazard without escalating the situation.

If a patient is seated at a table next to the firearm, it may be feasible to have the patient move to a better location or another chair so you can care for him more easily, thus isolating the weapon.

If a responder is entering an incident where the patient is aggressive and no weapons are in close proximity on entry, it may be best to create an exit strategy. Simply backing out of the scene without communicating with the patient could escalate the situation. So, it is important to communicate with the patient and let him know that you must get some additional equipment/medication from the ambulance and that you will be right back. Then, carefully exit the scene and request law enforcement assistance as soon as possible.

As you begin to care for your patient, it is best to get him in a seated position. A patient who is standing is more of a hazard to us physically and more difficult to treat medically. In addition, a patient who displays aggressiveness should remain seated before and throughout treatment. Placing the medical bag in front of the patient’s legs makes the equipment more accessible and adds an obstacle if the incident escalates.

During patient care, one crew member should provide the care and the second crew member could perform documentation. The second crew member should continue to monitor the situation and minimize or eliminate any potential hazards. One way to do this is to isolate the treatment area. If the patient is in the bedroom, the second crew member can position at the doorway and control access. If a family member is the individual increasing the aggression, the crew member can work on de-escalating the situation. I have found that family members are not purposely aggressive toward responders but rather they are confused, frustrated, and concerned for the family member, which manifests as aggression.

Among the best methods for de-escalating these individuals is to give them something to do to help their family member and help us. Ask the family member, “Can you get us a list of the patient’s medications so that we can properly care for him?” Serving a useful purpose may decrease the level of aggression or just turn the family member’s attention to becoming a part of the solution.

Request Assistance

It is hard to imagine that a patient or patient’s family member would become aggressive toward responders who are there to help; however, this is becoming more and more common. Inevitably, first responders will have to handle situations that cannot be avoided. Therefore, it is important for responders to identify potential concerns and request law enforcement assistance as early as possible.

The next issue is how to properly request assistance. With a hostile individual in front of you, you would not want to radio for law enforcement in plain English. Write into your policy a special code to use in a situation when dispatch is to request law enforcement response without needing clarification. Set several levels of law enforcement response, according to the situation’s severity. For example, a Signal 3 law enforcement response would be for an incident responders believe could escalate; a Signal 2 would be for a combative individual who is verbally or physically engaging with responders on scene; and a Signal 1 would be for when responders are confronted with a firearm, knife, or other circumstance where crews are in immediate danger.

The second part of implementing these codes is training on them and discussing them with dispatchers and law enforcement officers. A Signal 1 or 2 law enforcement response should receive a dedicated emergency response from law enforcement. Having a planned response ensures that the correct resources are sent when they are needed.

Reduce Hostility

Reducing hostility involves using de-escalation techniques to ensure personnel safety, to manage the patient’s emotions to regain behavioral control, and to avoid using restraints (if possible) and interventions that escalate tensions. For these techniques to be effective, responders must be trained appropriately. When communicating with an agitated or aggressive patient/individual, approximately 90% of all emotional information and more than 50% of verbal communication is through body language and voice tone. Therefore, responders should approach with a calm and clear tone to start reducing hostility.7

As soon as the responders identify a hostile individual, they should keep their distance and maintain a safe space. To determine a safe distance, look at factors such as other interior obstacles, other potential hazards, and the proximity of the hostile individual to hazards. Respect the patient’s personal space, and do not do anything that may be perceived as provocative. Maintain a nonaggressive neutral stance, stay calm, and watch facial expressions. Once again, body language or facial expressions, such as smiling, can cause the patient to feel humiliated and become angrier.7

The next step is for one individual to establish verbal contact. Avoid having multiple people interacting; it can cause confusion and aggression. The individual establishing verbal contact should attempt to build a rapport by asking simple questions, such as the person’s name and how he would like to be addressed. The responder should be polite, concise, and repetitive. Agitated patients often have a limited ability to process information, so repetition is important when making requests, asking for information, setting limits, or offering choices. The responder should carefully listen to what the patient is saying and repeat back part of what that person is saying. Repeating back shows the patient that you understand, but you need not agree with what he is saying. Engaging in the conversation shows the patient that you are listening, which may begin to de-escalate the situation.7

Another technique for building a relationship with an agitated patient is fogging. This is an empathic behavior where one discovers something about the patient’s position to agree with. If the patient is upset and says, “Your partner disrespected me,” you do not need to agree that what he said is correct, but you can agree that, “Yes, all individuals should be respected.” Overall, the goal is to find some common ground for agreement on which to start building.7

To maintain control over the situation, the responder must be able to set clear limits and do so respectfully. If the patient is talking about hurting himself or others, the responder should communicate that injuring himself or others is unacceptable; you may find it necessary to express the repercussions of his actions, in a nonthreatening manner. The patient may still be angry and acting out by punching walls; however, the responder should reassure the patient and attempt to coach him on staying in control. You can do this by asking him to calmly explain his concerns to you.7

The next step in deescalating an agitated patient is to give him choices. This can be a source of empowerment for the patient and can stop the aggression from escalating. Don’t deceive or be untruthful in the choices you offer. If you can offer something to drink, this could give him time to relax and create trust. The overall goal is to provide hope and be optimistic. This modern approach to handling aggression in a clinical setting has moved away from coercive interventions and over to a collaborative partnership, which can de-escalate the situation without forced medication or restraints.7

Escape

During the de-escalation phase, identify an exit strategy if de-escalation fails. Although you may be making progress with the patient, some external factors are beyond your control, such as family members who are becoming more hostile as you continue to try to de-escalate the patient. At this point, you should have already requested a law enforcement response, and it may be time to move to a safe location. If you cannot remove your crew from the house or structure, an internal room may be the safest location. Although not preferable, it may be the only option.

The question at this point is, “Do I just walk out?” Yes and no. When you believe your safety is jeopardized, the crew will have to determine the best way to get to safety, which may not be running out of the house. Turning around and running could escalate the situation. In handling the exit strategy, you could tell the patient that you need to go outside and talk to medical control to discuss the patient’s requests, although this seems a little counterintuitive to the point about not deceiving the patient. Our goal is not to deceive the patient; however, at this point in the incident, the patient has created an environment in which the responder and his crew no longer feel safe and must find a way to safely remove themselves from the situation until they receive additional assistance.

Self-Defense

Hopefully, at this point in the incident, one of the previous techniques for mitigating a hostile situation—avoidance, de-escalation, exiting, or requesting law enforcement—has resolved the concern. Unfortunately, several things can escalate the tensions and lead to an assault. Showing the patient disrespect and making physical contact are among those things that can “light the fuse.” In many assaults captured on a cell phone or in closed-circuit videos, putting your hands on an aggressive individual will cause a rapid escalation, likely leading to an assault. Just coming up to and pushing someone causes a dramatic increase in adrenaline. This adrenaline rush in an already aggressive individual is a recipe for disaster. So, our goal should be to maximize distance and eliminate contact.

If the hostile patient is already feeling overwhelmed, not in control, and hurt, do not add to his already existing emotional state by disrespecting him. I have heard responders make comments like, “I have better things to do,” or “You’re wasting my time.”

Once that fuse is lit, it is difficult to extinguish. For all agencies, this is the biggest area of liability: We do not know how the responders will respond if they are assaulted. All responders have personal experiences of hostile encounters and may not have been trained in how to handle these situations. Some responders may never have faced a physical confrontation and may have no training to fall back on. They may react violently with no self-control or may go right to the fetal position; both reactions are not good.

If a responder is trained in MMA and is faced with the same type of physical altercation, he may respond with his level of training, which includes a finishing choke hold that renders the patient unconscious. Every agency should make it known to their members how they want them to respond to this type of situation, and train them accordingly.

Treat

Overaggression gets people in trouble even after they have neutralized the hostile individual. Overaggression in the sports world is manifested when an MMA fighter knocks out his opponent and continues to land punches as the referee is trying to stop the fight. The same can be seen in street fights. The dominant fighter is still angry and decides to continue striking, kicking, or stomping an opponent who is no longer a threat.

Responders must be trained to maintain their composure and begin treating the patient immediately if there is no longer a threat. An excellent video detailing a few of these points depicts the 2011 Vancouver (Canada) Canucks loss of game 7 of the Stanley Cup Playoffs.8 The video, on YouTube, shows an angry citizen walking around yelling at two firefighters in the street. At one point, one of the firefighters grabs hold of the citizen and escorts him away from the fire apparatus. This point of physical contact is where the fuse is lit.

After the firefighter escorts the angry citizen approximately 20 feet back, the angry citizen strikes the firefighter and proceeds to back up. The angry citizen no longer takes an aggressive offensive posture; however, the firefighter reacts by walking toward and pursuing the hostile citizen. Fortunately, it appears as though the firefighter’s adrenaline drops, and he backs away and removes himself from the situation.

This situation could have deteriorated if the firefighter had continued to pursue and become the aggressor. Proper training can help prevent this from happening. In any event, providing treatment after the altercation helps prove that the responders were concerned about the patient’s well-being before, during, and after the incident.

As with all incidents, documentation is important. Make sure to document the account as accurately as possible. Write your statement of the incident as soon as possible so the small details are not forgotten.

Most responders have never received training on how to handle hostile situations, and chances are most won’t until their agency faces an event. Responders can still protect themselves by following the ARREST principles outlined above. Hopefully, in the future, there will be a reliable and an effective means to track the actual assaults on fire/EMS professionals. In the meantime, we know it is happening, and we know that they are not isolated events; therefore, every agency should take at least some preventive steps to protect their personnel.

Endnotes

1. National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. (2017, April 3). NAEMT OSHA Healthcare Workplace Violence Comment. Retrieved from National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians: https://bit.ly/2DZKlhK.

2. Smith, S, Maguire, BJ. (2013, August). Injuries and fatalities among emergency medical technicians and paramedics in the United States. Retrieved from U.S. National Library of Medicine: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23659321.

3. Legal Dictionary. (2015, June 3). Assault and Battery. Retrieved from Legal Dictionary: https://legaldictionary.net/assault-and-battery/.

4. Lectric Law Library. (2014, 25 July). Defense, Self-Defense. Retrieved from The Lectric Law Library: http://www.lectlaw.com/def/d030.htm.

5. Harvey, T. (2015, September 18). Fired Wal-Mart workers had a right to defend themselves, Utah’s high court says. Retrieved from The Salt Lake Tribune: https://bit.ly/2Fjo1Ay.

6. Kraemer, M. (2014, June 24). Employees who engage in self-defense at the workplace may still be entitled to unemployment compensation benefits. Retrieved from Law.com: https://bit.ly/2XWeohB.

7. Richmond J, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, Holland Jr, GH, Zeller, SL, Wilson, MP, . . . Ng, AT. (2012, February). Verbal De-escalation of the agitated patient: Consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. Retrieved from U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institute of Health: https://bit.ly/3fOI9XH/.

8. YouTube. (June 16, 2011) “Drunk Socks Firefighter after Canucks Lose.” https://bit.ly/3akRHJ5.

Philip Duczyminski is a 23-year veteran of the fire service, a captain, and the head of the Training Division of the Novi (MI) Fire Department. He has served with the Western Wayne County Haz-Mat Team and MI-TF1. A graduate of the School of Fire Staff and Command at Eastern Michigan University, Duczyminski is a certified Michigan fire instructor and an EMS instructor coordinator. He holds a black belt rank in multiple martial arts, with the highest rank being an 8th-degree black belt.