By STEVE FAULKNER

A high-functioning truck company can be the difference maker on the fireground and is often a key component that goes relatively unnoticed in today’s fire service. Despite the fire service evolving the role of truck companies, many firefighters are still not fully aware of the tactical advantage.

The truck company’s duties begin in the firehouse; it is there where you first develop and hone an in-depth understanding of firefighting tactics. This deep knowledge of tactics will help you identify what you should prioritize on arrival and dictate your responding course of action. Of course, your actions on the fireground will need to remain fluid and flexible and, subsequently, the processes you follow must be rooted in discipline and results based on several constantly changing variables.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

On arrival at every incident, the following questions should be on your mind:

- Is someone hanging out of a window or are there people reported trapped?

- Is this structure a commercial building or a residential structure?

- Are ground ladders likely indicated and, if so, where should they be placed first?

- Where is the main body of fire?

- Will immediate vertical ventilation be required?

- Should we delay entry until the engine company knocks down the fire?

- Can we enter at a different point to safely complete vent-enter-isolate-search (VEIS)?

You simply cannot lock every fire into a box and expect it to fit “the norm.” Expecting the worst allows you to prepare for the best; no fire you run is the exactly the same as another.

Although truck company functions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, sticking to the basics is a common ground all truck companies should strive to achieve. Using the acronym RECEO (Rescue, Exposures, Confinement, Extinguishment, Overhaul) to aid in ground ladder selection and placement, proper and timely ventilation, and creating an established culture that supports the prioritization of conducting searches in the correct areas at the correct time results in less time wasted and more people saved. A solid foundation in various tactics and the prioritization of these responsibilities will greatly increase the effectiveness of each task performed.

Ground Ladder Placement

The ground ladder is the most basic tool we carry and use and, subsequently, its selection should not be a last-minute decision. Knowing your response area and what your apparatus carries allows you to remove most of the guessing game from ladder selection when you arrive on scene. In general, ladder buildings in the following order:

- Fire floor,

- floor above,

- top floor, and

- the roof.

Of course, this must be applied with common sense; laddering the 10th floor of an apartment with the aerial ladder for a fire on the second floor of the same high-rise offers little to no tactical advantage. Conversely, focusing on laddering every window of a two-story house and neglecting pertinent interior duties may also offer little to no tactical advantage based on arrival conditions.

Base your ladder selection and placement on your ladder priorities such as rescue, egress, ventilation, and searchable areas. Searchable areas are defined as locations within a structure where an interior team can perform a rapid primary search for victims.

Survivable areas are survivable—areas where a victim might have looked for an escape; sheltered; and, in the best-case scenario, might have the best chance of survival. Understanding the difference between the two dictates your ladder placement as well as the sequence in which those actions are performed. Once that is determined, you can move on to the next tactical objective.

Windows with fire showing/venting are not searchable areas, entry points for firefighters, or survivable areas for any occupants within that area. Also, always place ground ladders in a position for rescue and, barring an emergency, never move them unless by the exiting VEIS firefighter who placed it there. Doing so ensures that the ladder he saw at the window when he entered the structure is still there should he need to make a quick exit.

The single-family dwelling is a great place to start when discussing ladder placement because the ladder priorities can change vastly. For example, photos 1-4 shows sides A-D, respectively, of a two-story, detached, Type 3 single-family residential home found throughout our jurisdiction. In Washington, D.C., these homes are usually constructed of masonry brick walls with a wood roof and floor system and typically have three to four bedrooms, a basement, and an attic, some of which are livable spaces. A thorough 360° walk-around during the initial size-up indicates that there are a total of nine windows on the second floor as well as two in the attic. However, these windows are not ladder priorities.

(1) Side A of a two-story, detached, Type 3 single-family residential home. (Photos by author.)

(2) Side B of the home.

(3) Side C of the home.

(4) Side D of the home.

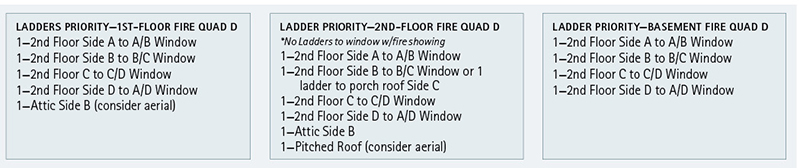

To show the sheer amount of decision making a truck company will need to do on what many might consider a “routine” incident, let’s use this home to show how much things can change if we have a working fire and a report of an occupant possibly trapped on the second floor. For training purposes, there is fire showing from side A on the first floor in quadrant D and a victim reported trapped on the second floor. Using knowledge of building construction and keeping the forementioned ladder priorities in mind, we can place four to six ladders rapidly in tactically advantageous positions based on the fire location and victim location, cover this home in its entirety, and effect rescues and ventilation simultaneously. Figure 1 shows one way of covering the entire home. (Hint: It appears that two of the three rooms share multiple windows. This offers a huge, time-saving tactical advantage.)

Figure 1. Possible Laddering Tactics at a Two-Story, Detached, Type 3 Single-Family Residential Home

Figure by author.

Another possible location for the ladder is the roof of the setback addition. Doing so gives us access to two windows of two separate rooms, a bedroom, and a bathroom. We can tell the middle window on the C side is most likely a bathroom because of its smaller size when compared to the other second-floor windows. (Note: If your company chooses to ladder the setback addition to accomplish access to that particular bedroom and bathroom in one shot, you do not need to prioritize the placement of an additional ladder to the B side second-floor window.)

This home also has high first-floor windows, which presents an additional challenge. Although emergency egress from these windows by firefighters and citizens alike would be low-risk, rescue of a victim or firefighter entry would require using one of a multitude of options. Many truck companies have begun carrying modified straight ladders of five- or six-foot lengths and some are equipped with combination A-frame/extension ladders. If your company doesn’t have one of those options available, you can always use a straight ladder at a low climbing angle. Again, there is no “must-do”; the scenario was presented to show an option and encourage a sound decision-making process.

Remember, trying to do as much as you can with as little as you can is a solid option when trying to open up your fireground “playbook.” There is no need to lock yourself into a box, but your goal should always be to get the necessary number of ladders up to the necessary locations as quickly as possible. A first-floor fire should not prevent you from laddering the attic and roof. However, you would make a bigger difference placing ladders where they need to go first, especially if you are operating on a short-staffed truck company. A ladder to the roof is not an operational priority on a home of ordinary construction with a fire anywhere other than on the top floor, as vertical fire spread to the roof is very unlikely. Conversely, if this were a balloon-frame home or had knee walls, a ladder to the roof would be a priority and indicated, regardless of fire location.

I cannot stress enough that your size-up changes everything. The fireground is situationally dependent. What does not change is the benefit of making that decision quickly, placing ladders to your ladder priorities, and moving to the next operationally critical task. This is how a truck company can make a bigger difference on the fireground.

Ventilation

Secondary to ground ladders, coordinated and effective ventilation is another critical role for the truck company. In most fire department textbooks, ventilation, in its simplest form, is “the systematic removal of heat, smoke, and gases from an environment.” At its core, we want the fire to go out, make it safer to put it out, and increase the likelihood that the fire does not seriously injure or kill people. Proper ventilation improves interior conditions, saves lives, increases visibility, and makes our job as a search company much easier.

(5) A firefighter vents a window by ground ladder.

(6) Venting the window nearest the seat of the fire.

Ventilation must be done early in the incident and should be completed in conjunction with the engine company’s attack on the fire. Similar to improper ground ladder placement, ventilating the wrong place at the wrong time can have disastrous consequences for interior firefighters and victims alike and, conversely, not ventilating the proper windows can produce the same negative results. To better understand the “when” and “where” of ventilation, firefighters on truck companies must have a firm grasp on fire behavior, be able to recognize the paths of least resistance, and be familiar with building construction. Too often, firefighters on truck companies ventilate late into the incident or not at all. Sometimes, firefighters overventilate or ventilate areas that have no bearing on conditions or results. Many department standard operating procedures (SOPs) spell out directly where responding companies should ventilate, but keep in mind that an SOP mentioning a particular area of ventilation as a responsibility is meant as a guide and, depending on the incident, that action may actually not be tactically necessary or indicated. Again, when it comes to truck company operations, we must break out (no pun intended) of our tunnel vision/robotic mindset, remain fluid, and employ tactics that situationally make sense.

Is fire showing from a window? If so, some of our job is already done for us. What about when there isn’t fire showing or the fire is on a different floor? Conditions like this require us to read smoke, accurately predict fire spread, and understand the law of probability as it relates to the likely victim location if anyone were trapped. All fires in structures rely on steady air intake and exhaust to sustain combustion and, consequently, reading smoke can direct exterior truck company crews to the correct ventilation priorities.

(7) A working basement fire with intact windows at ground level.

(8) Here, the fire self-vents from the window.

When we enter a structure through an opening, our entry point is often the only opening. Without a clearly defined escape path for heat and gases, we are, in effect, creating an opening that could quickly turn into both an intake and a vent. To combat this, many fires indicate that horizontal ventilation be completed as close to the fire and opposite the direction from which the engine company is attacking. While completing this task, ventilation must be done in conjunction with the engine company’s attack; if possible, be prepared to isolate the room to limit autoexposure, if the need arises. If it is a first-floor fire, vent the first floor first. In a second-floor fire, vent the second floor first. Simple, right?

A basement fire is where things change a bit for everyone. Basement fires are a different animal because basements often have limited openings; can be difficult to access; and, by the numbers, are not as prominent as they are at ground level and aboveground-level fires. As a truck company, we make or break this incident.

Basement fires are among the most underventilated fires we run. Many reports from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, including one on the Cherry Road Fire in Washington, D.C., cite improper ventilation or the lack of ventilation as a contributing factor to the loss of a firefighter. As a truck company, victims above, ventilation of upper floors, and the control of interior basement stairs are our number-one concern. In many areas, the interior basement stairs are located under the stairs, leading to the upper floors and, subsequently, the basement doors.

In a basement fire, the basement stairwell can effectively function as a chimney, and the area at the top of the stairs may be completely untenable. This phenomenon hinders rescue efforts on upper floors and makes it more difficult for additional engine companies to protect those efforts. Because of this, we must control the basement door, and conducting ventilation near the top of the basement stairs opposite the primary entry point should be considered early into the incident.

Also, place utmost importance on ventilating as much of that area as you can, working from near and outside the basement stairs. In many houses including row homes, this can be as simple as ventilating the first-floor rear area of the home. Pay particular attention to the first-floor rear doors, as they could be more securely fortified and unlikely to be forced by other responding units. Doing so not only aids in ventilation but gives interior crews another egress point.

When all of this is said and done, ventilation of the upper floors must also remain on our radar. By operating in this manner, we give the heat, smoke, and gases a place to go (other than around any firefighters operating above the basement fire).

Note: Poorly timed ventilation of a basement window prior to completing necessary exterior tasks on upper floors (i.e., laddering, VEIS, removal of bars) can make things quite difficult and dangerous to accomplish. Try to get your exterior work above a basement window done quickly prior to venting that window. A basement fire does not relieve us from accomplishing our duties on upper floors.

Search Priorities

When comparing modern-day fires to legacy fires, we are “behind the eight ball” from the start. Today’s fires burn eight times faster than legacy fires and produce 200 times the amount of smoke. This poses a challenge to victim survivability. In 2021, there were more than 1,700 fire fatalities nationwide and, unfortunately for occupants, escaping from house fires isn’t getting any easier, as hotter and faster-burning fires continue to occur. We still need to search, do so faster and more efficiently by differentiating between searchable areas and survivable areas, and direct our efforts appropriately.

Although there are many resources available, Firefighter Rescue Survey’s The First 2,000 Rescues is a great resource to consider. The data in these surveys increases our knowledge of building construction, fire behavior, and functioning as a coordinated team on the fireground and helps us predict more accurately the probability of victim location and, subsequently, conduct more effective searches.

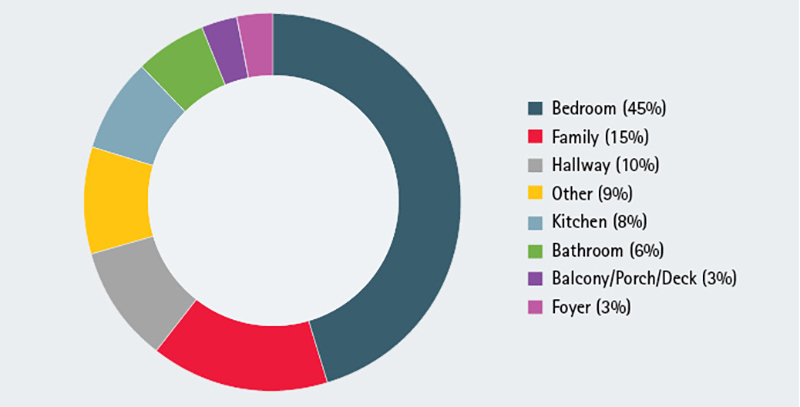

An example of this is your truck company being dispatched for a house fire at 0200 hours. Using the data, we can deduce the following:

- The call was dispatched at 0200, most likely the time someone would be trapped inside the home.

- If someone is trapped in the home, there is a 45 percent chance he is in a bedroom. That is almost half the time! In the case of the two-story home that follows, the bedrooms are likely to be located on the second floor, although it is possible that the home has a first-floor bedroom.

- In the case of searchable vs. survivable, we will not waste time searching a fully involved room or floor, and instead we will focus our search efforts on the areas of the home closest to the fire that fit our probability parameters. This can be done in multiple rooms by interior and exterior teams through interior search and VEIS.

Figure 2. The First 2,000 Rescues: Victim Location vs. Total Recorded Rescues: Floor

The interior and exterior teams have the same goal but with different search priorities. Although the interior team must work around an attacking engine company, fire conditions, and potential hoarding issues, the exterior team is able to pick and choose their entry and exit points on the structure, giving them a slight advantage to reach a victim quicker. On arrival, search the area for residents or bystanders who have pertinent information about potential victim location. From there, initiate your plan of attack.

For example, using the same times mentioned above for our two-story single-family dwelling, our interior crew would begin their searches on the fire floor, searching behind the entry door and the hallway on the way to the area nearest the fire while working their way out. Statistically, the least likely location to find a victim would be the foyer, hallway, and bathrooms. Does this mean we shouldn’t search them? No. However, we shouldn’t dedicate a lot of time to them during a rapid primary.

A complete and thorough primary search of the entire home must be completed on every fire. Street-smart tip: In the event you enter a bathroom, ensure you search the bathtub. Some of that six percent of persons found in bathrooms were, in fact, in the bathtub. In terms of searchable vs. survivable, conduct your primary search in survivable spaces. The fire room is not survivable; the rooms adjacent to, across from, and above the fire room are, especially if interior doors are closed. The interior team should direct their primary search focus to these survivable spaces to increase the likelihood of locating and removing trapped occupants.

While the interior search is underway, the exterior team can place ground ladders to the appropriate ladder priorities and, if indicated, complete VEIS on these rooms. These firefighters are statistically more likely to encounter victims in these bedrooms. When performing VEIS, although it is not always possible because of staffing, it is recommended to operate in a team of two. With a two-firefighter VEIS team, one firefighter enters the room and the second remains at the window on the exterior with a thermal imaging camera (TIC). In any case, clear and remove the window and frame completely and, if equipped with a TIC, conduct a scan of the room for victims and heat prior to entry. If it is safe to enter, sound the floor, proceed immediately to the door to isolate the room, and begin your search. Note: If no door is present, remove a closet door and place it over the opening.

Figure courtesy of FirefighterRescueSurvey.com.

Figure 3. The First 2,000 Rescues: Victim Location vs. Total Recorded Rescues: Room/Area

Figure courtesy of FirefighterRescueSurvey.com.

Figure 4. The First 2,000 Rescues: Time of Day vs. Total Recorded Rescues: Time

Figure courtesy of FirefighterRescueSurvey.com.

When searching the room, pay particular attention to the area underneath the windowsill; on, under, and around beds; and near the bedroom door. Be cognizant that beds come in many forms, and the one you may come across during your search could be a bunk bed. Many bunk beds have desks or dressers at floor level and a single bed above, so be on the lookout for those. You can miss small children and small adults on large beds easily if you are not feeling the entire bed. Reach up, reach back, get on the bed, and move blankets and pillows; cover every inch you can above and below.

Also, complete a rapid search of the floor, clutter, and closets. Get a good feel on everything because, with a gloved hand, you may think you’ve found a victim when you haven’t.

Although it is important to do a thorough search, remember that it is equally important to complete an efficient and a rapid search. Do not get in the habit of second guessing your search; if no one is located, chances are you did your job correctly and should exit to move on to the next search priority.

Keep in mind that victims are not wearing self-contained breathing apparatus or structural firefighting gear. Get the victim out of the immediately dangerous to life or health environment as quickly as possible. However, dragging them through a superheated, smoke-filled hallway, regardless of whether you can see fire or not, drastically reduces any chance of survival. Isolate, ventilate, and move them to the window. If removing them through the interior would do more harm than good, do what you can to make the area more tenable for them and try to use alternative exits.

Each incident will have its own challenges as well as its own unique conditions that change the way we need to operate. We must remain disciplined and aggressive and maintain a versatile “toolbox.” Ground ladders, ventilation, and disciplined search techniques are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to developing an effective and efficient truck company, and mastering those skills will put you, your company, and the citizens far ahead of the curve.

STEVE FAULKNER is a lieutenant for the District of Columbia Fire Department in Washington, D.C.

Stephen Faulkner will present “Make Truck Work Great Again: Urban and Rural Truck Company Operations” at FDIC International on Friday, April 29, 2022, at 8:30 a.m.-10:15 a.m.