BY MARK ROSSI

As firefighters responding to a structure fire, we all want to be “first due” or first in on the fire. However, as firefighters responding to incidents, we must be disciplined regarding the safe and effective placement of our apparatus on arrival or we will fail to execute what it is we have been called to do.

|

| (1) Fort Lauderdale Engine 46 arrives at a house fire. The engineer pulled slightly past the structure to give the officer a view of three sides. This is standard practice in Fort Lauderdale. (Photos by author.) |

Our engine company recently responded to a one-story, wood-frame residential structure fire in our second-due territory. The fire was reported around 10 p.m., and the first engine was on scene a few minutes later after the initial 911 call.

The house was in a residential neighborhood with limited access. It backed up to a cul-de-sac and wooded area. The street was also poorly lit; visibility at best was slim for incoming units. On arrival, we were assigned water supply. The first-due engine pulled slightly past the structure, called a “working fire,” and started the initial fire attack. The closest hydrant to the scene was approximately 400 feet just south of where the initial engine parked.

After our engine had laid approximately 300 feet of five-inch large-diameter hose (LDH), we were forced to halt our forward lay because a rescue truck (otherwise known as an ambulance by most departments) parked directly behind the first-due engine, in the middle of the street, blocking our only access to that engine. Because of the poor placement of the rescue, securing a water supply became more difficult and delayed. We ended up hand-laying an additional 100-foot section to the attack pumper, but we finally did get a water supply.

Placement of fire apparatus, according to Captain Bill Gustin of Miami-Dade (FL) Fire Rescue, requires the foresight to visualize what the fire, fire building, and fire will look like later in the incident. It also requires the foresight to envision what resources the incident commander (IC) may need to mitigate the hazards. Luckily, the fire discussed above was quickly extinguished with no loss of life and minimal smoke and fire damage to the structure. In fact, crews ended up rescuing two dogs from the structure. Had the fire doubled in size, spread, or reached a level beyond our control, the end result could have been very different and much more drastic because of the delay in obtaining a water supply caused by poor apparatus placement.

|

| (2) Fort Lauderdale Tower Ladder 2 arrives on the scene of a strip mall fire. Notice the placement of the apparatus in the immediate front of the structure. Engine 47 (photo bottom) was the first-arriving engine company. It is placed well out of the way of the aerial. |

Apparatus Placement on the Fireground

Effective apparatus placement begins with the first units to arrive. Base the positioning of the initial arriving engine, ladder, and rescue on the initial size-up and general conditions on arrival. First-arriving companies should place themselves on the fireground to maximize themselves and their assignment. Later-arriving units should position themselves in a manner that supports the initial actions and allows for expansion of the operation. Regardless of the fire type (residential or commercial), the placement of all apparatus on the fireground should reflect one of the following:

- A standard operating procedure (SOP) for first-arriving companies.

- A prearranged staging procedure.

- A direct order from Command.

- A conscious decision of the officer assigned to that apparatus based on existing or predictable conditions.

The first-arriving officer has several factors to consider with regard to apparatus placement and positioning:

- The location of the fire and how it will be reached.

- The possibility of damage to the apparatus from heat, convection caused by the heat, or structural collapse.

- The positioning of aerial devices.

- The positioning of later-arriving units.

- The proximity to the closest water supply.

Obviously, we cannot always pinpoint exactly where the fire is or how it will be reached. Every fire presents different challenges. As firefighters, most of us are accustomed to responding to the front of the structure where the address is usually displayed. From there, ICs may assign units to position to the rear or sides of a structure based on conditions found on arrival. Driver-engineers share the responsibility with the officers of their units to also consider secondary means of access and egress to the fire building-in other words, there may be more than one route to the scene.

Often, we are faced with narrow streets, one-way roads, or dead ends. Responding units need to realize their route to the fireground is equally as important as placement. Is the street large enough for multiple apparatus to park close to the scene? Where is the water supply, and how will it be accessed? Did we leave room for the first-arriving ladder truck? In what order are we arriving, and what resources are needed immediately at the scene? These are just a few of the many questions drivers and officers need to consider when responding to emergencies, especially if their unit is one of the first on scene.

Later-arriving fire companies may or may not have preassigned responsibilities. Most of the larger departments have fireground SOPs in place that assign each arriving unit to a particular location and task on the fireground. If your department does not have an SOP on fireground operations, your best bet would be to stage away from incident command and wait for an assignment. This is often referred to as Level II staging. It reduces the congestion on the fireground and also takes pressure off the first-arriving officer conducting size-up and initial actions.

Command must always maintain some level of awareness with regard to tactics on apparatus that are actually working vs. those that are not working or are “taxis.” Apparatus not working should be left in staging. This is easier said than done because often we all want to get to the scene as safely and as quickly as possible, not realizing how congested the scene quickly becomes.

In Fort Lauderdale, when our units respond to a residential structure fire, our SOPs state the first-arriving engine proceeds directly to the scene for size-up and fire attack. The second-due engine is responsible for water. Our first-due ladder arrives on scene and begins truck company operations (primary search, ventilation, and securing utilities).

From there, later-arriving engines stage on scene in the direction of travel and report to command. Our second-arriving ladder is assigned as the rapid intervention team. The first-arriving rescue company assists the first-due engine crew with vent-enter-search and stretching the backup line. Second-arriving rescue companies establish patient care or the medical sector. Every arriving apparatus has a specific assignment based on the fire type per our SOP. We are an aggressive fire department and, for the most part, work as a “well-oiled” machine on the fireground. Like most large fire departments, not only is each of our apparatus assigned a task but each individual on the units also has assignments based on position and rank.

According to John Norman’s Fire Officer’s Handbook of Tactics, a safety consideration when placing apparatus is to think of fire apparatus as an expensive exposure: We should position working apparatus in a manner that considers the extent and location of the fire and a pessimistic evaluation of fire spread and structural failure. Heat and other hazards may be released with structural collapse. We should not park near low-hanging wires, another dangerous situation. A general rule of thumb is to position the rig at least 30 feet away from involved buildings regardless of condition. More times than not, greater distances are required when conditions have deteriorated.

Another thought to consider is positioning the apparatus where it can easily be moved, repositioned, or readily available when cleared by command to return to service, particularly in areas with only one way in and out (i.e., alleys, driveways, and cul-de-sacs). Apparatus function should regulate placement. Many times we reverse this rule by virtue of poor placement, limiting the options, or eliminating functions we can assign to that unit. Obviously, we can’t be positioned outside the “collapse zone” on every call, or our ladders would be useless and we would have to carry a mile of hose. However, the smart IC must be able to recognize the signs of impending collapse and get the personnel and apparatus out of the zone in an orderly fashion.

Results of Improper Placement

We have all been on fire scenes where we have witnessed poor apparatus placement, from the engine that parks directly in front of the structure to the ladder truck’s access blocked in by other engines to the rescue unit positioned on a street that will not allow other units to pass. This is a result of the negligence or inexperience of the driver. The following is a short list of some of the results that can occur when apparatus are inappropriately positioned on the fireground:

- Apparatus accidents or damage from having to move or reposition.

- Delay in getting initial lines (and backup lines) in place.

- Delays in water supply. Without water, the fire does not go out!

- Delays in search and rescue and having the available personnel on scene to conduct searches.

- Delay in ventilation.

- The fire doubles in size or intensifies.

- Worst-case scenario: A firefighter is injured or killed.

The bottom line is that we must do a better job of policing ourselves on the fireground and positioning correctly to prevent the above problems.

Positioning Considerations First-Due Engine Placement (Fire Attack)

With the tactical fireground zone being defined as the area at or near the fire building, many departments follow a standard concept in which the first-arriving engine company proceeds down the street, places the apparatus just past the fire building, and begins the initial fire attack. This position allows for the following:

- Shorter and more easily managed hose stretches because the hosebed faces the fire building.

- In some situations, the first-arriving officer can view three sides of the building during this process and determine which resources he will need to use first.

- Leaving the front of the building open for the first-arriving ladder company.

Second-Due Engine Placement (Water Supply)

If the first-arriving engine company has not secured its own water supply, then the second-arriving engine company is assigned the responsibility of water supply. The second-due engine has several choices from which to chose based on the given situation, personnel to complete the assignment, available water sources, and maneuverability on the fireground. Do conditions warrant a forward lay or a reverse lay? Do conditions require the engineer to tandem pump or relay pump, or does the engineer need to set up for drafting? An experienced and knowledgeable engineer and officer will be able to quickly work together and decide which option is best given the situation. Regardless, this decision needs to be a fast one, as without a solid water supply, we are doomed to fail from the start.

LDH limits general access to the fire scene as the fireground operation becomes larger and more time consuming. Unit officers and command must work to get all apparatus well placed on scene. Lines should be stretched with attention to the access problems they present. A good rule of thumb is to try and lay lines on the same side of the street as the hydrant. If you need to cross over, do this as closely as possible to the fire. This will allow more units access to the scene if needed.

First-Due Ladder

In many towns and cities, it is critical that the first-due ladder company be given the key position in front of the fire building. This area is reserved for the ladder company to facilitate placement of ladders. Allowing enough room for the ladder company to maneuver is critical. Depending on the type of aerial device and the conditions present, the ladder company officer may want the turntable of the apparatus on the corner of the building to enable the ladder to reach two sides if necessary. In larger buildings, two ladder companies, at both corners of the building, may allow aerial access to three sides of the building.

To ensure placement concerns for the arriving ladder company, the second-due engine company has to allow the approaching ladder company the opportunity to proceed into the block before it does. More times than not, we all know this is not the case. If the ladder company is not within sight, the engine company officer may elect to go to the scene and drop its supply line hose into the attack pumper and then proceed to the nearest hydrant (reverse lay). This makes room for the aerial device to be placed directly in front of the structure.

Aerial Reach

Aerial reach is also an important consideration. The two common types of aerials are the mid-ship and the rear-mount ladder, or platform, which are manufactured in a variety of configurations. Articulating booms are also available, but they are not addressed in this article. Determine what part of the building your aerial can reach and scrub. Aerial reach is generally rated and advertised as the maximum vertical reach at the 75° climbing angle.

Per IFSTA’s Aerial Apparatus, the acronym RECEO stands for Rescue, Exposures, Confinement, Extinguish, and Overhaul, all of which are fireground priorities. An aerial arriving at a fire should be used to support the operation. Overall strategy and tactics at every structure fire should include proper placement and use of the aerial. Preplanning and SOPs must include the key concepts of aerial placement and operation based on occupancy and construction type.

Regardless of the arrival order, each unit, not just the truck, needs to be positioned with consideration for the other. The first-arriving units of departments that do not have an aerial responding on the initial alarm must consider aerial placement; otherwise, an aerial requested later may not be able to access the fire.

Arrival order should also dictate the tasks or functions the crew will perform. For the aerial to support the tasks, it must be properly positioned. The first-arriving aerial should be positioned for rescue. If rescue is not an issue because the fire is too far advanced and the IC is operating in a defensive mode, focus aerial placement on aerial stream deployment and exposure protection, with the aerial outside the collapse zone. In many cases, a pumper is the first unit to arrive and go to work. Unless SOPs dictate otherwise, it is common for the pumper to arrive just ahead of the aerial, even when both units respond at the same time from the same quarters.

Commercial Structures: Strip Malls

Many single-story strip malls extend horizontally for hundreds of feet. Newer strip malls tend to have extremely tall parapets on the front or false storefronts. In these situations, position the aerial to cover two sides of the building so firefighters can access the roof safely and, if needed, can put a master stream in service rather quickly.

There is a tendency for both newer and older strip malls to have a traffic lane immediately in front of the stores. This can cause firefighters and officers to position the aerial too close and within the collapse zone. It’s always a good idea to position 1½ times the height of the building to ensure your unit is out of the collapse zone. It can also trap apparatus and prevent repositioning because of fleeing customers and their private autos attempting to leave the parking area.

Preplanning by first-due companies should focus on where companies should position to meet their needs while in a safe location. Older strip malls may have limited parking in the front and may be relatively close to the street. In these cases, it may be best to have the aerial (and perhaps the engine) position on the street, provided the aerial can reach the structure. Again, preplanning is key.

The success of the first-arriving truck company is contingent on a number of factors: The crew should be properly equipped, well trained, and adequately staffed and should respond using the safest and most efficient path of travel from the station to the incident scene. From there, the initial spotting of the apparatus is a critical point in the company’s capabilities to carry out the four primary truck company functions on arrival: primary search, rescue, ventilation, and forcible entry. Allowing the proper access to the best vantage point for the truck will assist in these functions.

Additional Arriving Nonsuppression Units

Every fireground scene will require a certain number of suppression units, but what about the nonsuppression units such as chief officers, rescue units (medical ambulances), and the squad? These units are mostly support units, but they play an important role on the fireground. When positioning comes to mind, spot these support units in a safe position that will provide the most effective treatment of fire victims and firefighting personnel while not blocking the movement of other apparatus or interfering with firefighting operations.

Rescue units must also provide for ambulance access to the treatment area in situations involving patient transportation. Position command vehicles to allow the IC the maximum visibility of the fire building and surrounding area and the general effect of the companies operating on the fire. The command vehicle position should be easy and logical to find and should not restrict the movement of other apparatus.

Unfortunately, police vehicles often end up where we don’t want them. In Fort Lauderdale, they usually are the first to arrive. Often, they restrict our access or block a hydrant. This is just another hindrance we have to deal with when operating on the fireground.

The above is not intended to change what is working for you but to provide additional thoughts on establishing and delivering water. It all comes down to the best way to provide an efficient, effective, and safe supply of moving water in your jurisdiction.

Placement for Motor Vehicle Accidents

When placing apparatus for motor vehicle accidents, you must seriously consider firefighter safety. Every year, firefighters are injured and killed while operating at vehicle accidents and fires on public roadways. Several placement methods can help avoid such tragedies. They include diagonally blocking lanes with apparatus and having the police stop all traffic until the scene has been stabilized. We don’t need cars driving by at 50 miles per hour as we try to extinguish a vehicle fire on the side of the road. In today’s technology-driven society, many motorists are on their phones, texting while driving, and taking photos as they approach the accident scene. Most are not paying attention to what they are doing and they end up causing an additional accident that could have been avoided. Don’t rely solely on warning lights and traffic directing arrows. Some drivers are drawn to all the excitement.

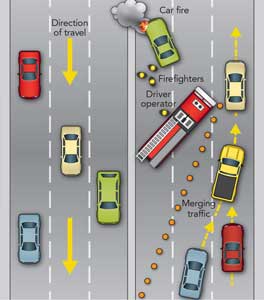

One theory proposes positioning the apparatus at an angle toward the middle (left side) of the highway (Figure 1). The best reason is that the direction in which the truck is pointing supposedly tells the motorists the direction in which we want them to merge when they go around the scene. We can then put all our road rescue tools on the side of the accident where they are safely accessible. The apparatus, in turn, will be a barrier between oncoming traffic and the crews working on scene. Finally, driving away when clearing is usually easier for the operator. Most roads are open with shoulders and medians unless you are working on a major highway.

| Figure 1. Positioning Apparatus for Safety on a Roadway |

|

Your crew on scene is your first priority. The patients and other traffic are secondary. Park to protect your crew; point away from the scene, and use caution when dismounting. The pump operator needs to use caution when working at the panel. If someone hits the apparatus, the damage is more recoverable than if they hit you or another firefighter working on scene.

Whenever possible, try to angle your rig to prevent personnel from exiting the apparatus with exposure to the traffic lane. The number of lanes and whether the accident is in the center divider, off to the shoulder, or in the middle of the highway dictate whether you have to close the highway and divert traffic.

In Fort Lauderdale, we will take an extra lane if it means more protection for our crews working on scene. A typical response profile on vehicle extrications will bring two additional engines and a ladder company. The additional units will position themselves on scene to block fire working crews from the flow of traffic.

No accident is worth a firefighter’s getting hurt or killed. Engine companies weigh a lot. Let the drunk driver hit the back of your engine instead of you, the involved vehicles, the ambulance, or the patrol car. Use your engine to protect yourself.

Positioning fire apparatus at the emergency scene is not difficult, but it does take some common sense and experience. You must consider the current situation on scene, what is needed immediately, and what will happen as the scene progresses. Making a positioning mistake with your company can severely delay your ability and that of additional apparatus to perform. This can create ongoing difficulties at an emergency scene. To avoid these and other issues, take some time with your crew to walk the target hazards in your area, preplan your first- and second-due territories, and talk with other experienced engineers about the most effective operating locations.

References

Gustin, Bill, “Positioning Apparatus for Maximum Efficiency and Safety,” Fire Engineering, February 2010.

“Apparatus Operations,” Homewood (FL) Fire Department standard operating procedure, Aug. 1, 2002.

Robertson, Homer, “Proper Aerial Placement on the Fire Ground,” FireRescue, 3/21/13.

Norman, John, Fire Officer’s Handbook of Tactics. Fire Engineering Oct. 1, 2004.

Mark Rossi, a 14-year veteran of the fire service, is the driver/engineer on Engine 8 assigned to A-shift in the Fort Lauderdale (FL) Fire Department, where he has served for the past nine years. He is a fire instructor for Coral Springs Fire Academy, teaching driver-engineer and hydraulics, firefighter survival, minimum standards, and live fire training. He has a bachelor’s degree in finance and a master’s degree in business from the University of Florida. He is pursuing a Ph.D. in emergency management.

Additional Links

Firefighter Training Drill: Outside-the-Box Apparatus Positioning

Positioning Apparatus for Maximum Efficiency and Safety

APPARATUS POSITIONING : EARLY DECISIONS SAVE THE DAY

Positioning Aerial Apparatus When You’re Not First Due

Fire Engineering Archives