By Nick Wilbur

This article will follow a fire department that is getting its first new aerial device and is starting a new ladder company. It does not matter who the manufacturer is or the type of aerial device. We will look at the progression of training, policies, and actions that need to take place for the first and subsequent aerial ladder purchases. We will not discuss the specification process in detail; seek help from someone who has done this before and who has done it right.

- Aerial Apparatus Stabilization: It Starts from the Ground Up

- The Ins and Outs of Basic Aerial Operations

- AERIAL OPERATIONS FOR LOW-RISE BUILDINGS

- Safe and Effective Aerial Ladder Operations

Do not rely on the salespeople to determine what you need. Perform a good needs assessment and define the mission of the vehicle before you begin the specification process. Experts who do this more than once every 10 to 20 years will be an invaluable asset throughout the process. One note of advice: Do not forget about ground ladder storage and selection; after all, you are purchasing a ladder truck. It should have ladders on it! We will focus on when the ladder truck is delivered and the actions the department and personnel need to take on delivery.

Apparatus Committee and Specs

Although the ladder truck has already been specified and delivered, the apparatus committee’s work is not done. They must pass along some information only they know. Since most fire trucks are custom built to the customer’s specifications, you must inform those who will be driving the apparatus what you specified. For example, make drivers aware that the apparatus includes many auxiliary braking systems in addition to their aggressively downshifting the apparatus to help it stop. Most drivers would be unaware of some of this much-needed information unless they looked at the vehicle specs. This also goes for the manufacturer. National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1901, Standard for Automotive Fire Apparatus, states that all ladder trucks should be delivered with an operator’s manual. This is crucial to understand how the aerial device jack system functions and how you need to set up the vehicle for safe and successful operations. Most operator manuals are very general and cover a variety of aerial devices and setups. Unfortunately, you must specifically ask for a custom manual that is written with your specified features and options; this costs money. This is where knowing the specifications comes in handy. Inform those who will drive and operate the vehicle of any options it includes so they review the applicable operator’s manual section.

On delivery, manufacturers provide a vehicle demonstration and familiarization in which they show you the knobs, levers, switches, and warning stickers. This is much needed for a new vehicle so that you can understand the vehicle you are getting and some of best practices and hazards. However, this is NOT training! Manufacturers are not qualified to (and should not) provide quality training on positioning and operating this apparatus at a working fire or emergency scene. They do not train drivers to compare the differences between current vehicles and the new one delivered. You and your department must ensure that members receive adequate training to drive and operate the aerial apparatus. If you do not have the expertise in house, seek out someone with aerial training experience to come in and provide the needed training.

The First Day

Most times, the first day the new fire apparatus appears, it will make a brief appearance at the fire station before heading to the local dealer for some last-minute tool and equipment mounting and other vehicle prep. Or, it may go to the dealer first. Depending on the department’s size and policy, some firefighters will only see the vehicle when it is ready to be placed in service. Some departments spend weeks and months giving members the opportunity to drive and operate the new device to ensure they are competent and comfortable with the apparatus before placing it in service.

Still, many will drop off the vehicle, saying, “This vehicle is in service; now go train on it!” This scenario is not the way to handle it. In January 2009, two Kilgore (TX) firefighters died in the line of duty during new aerial training. Aerial apparatus today are powerful and exert forces that must be understood. Take the time, read the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health report on the Kilgore incident, and consider what can be done to prevent it from happening again.1

Driving and Operation Training

Among the most important things I have learned while driving and operating different types of aerial devices is that you must have wheel and operating time to feel comfortable with one. Comfortability breeds confidence; confidence breeds proficiency. This all takes time and repetition; it cannot be accomplished in one day or even one week.

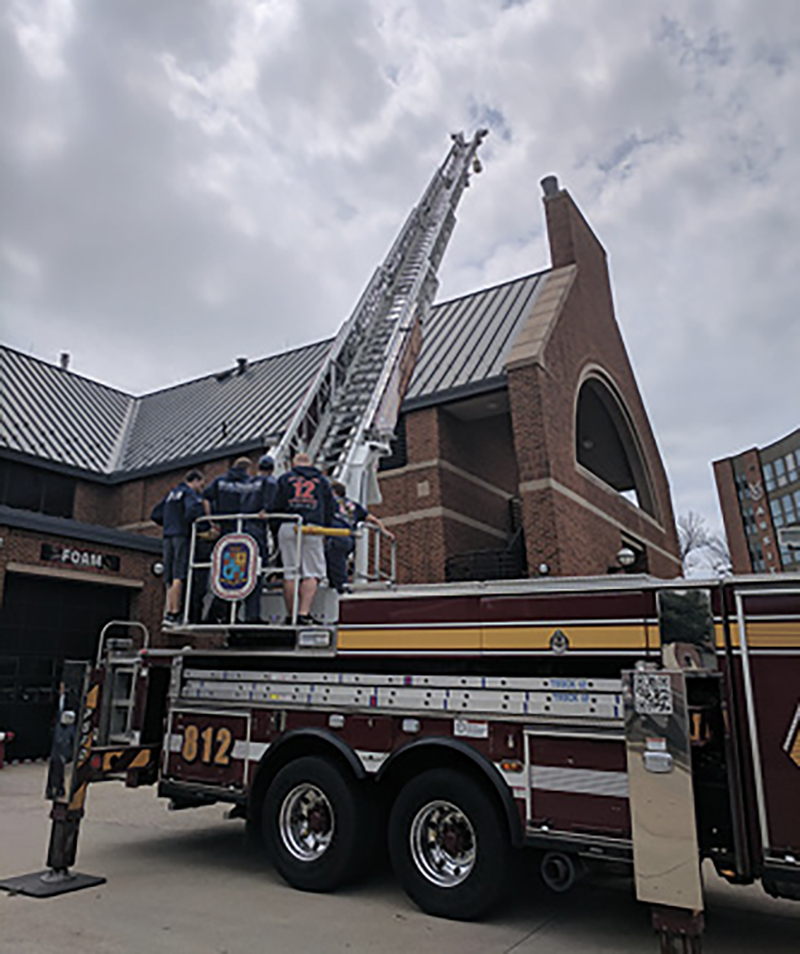

(1) College Park (MD) Volunteer Fire Department Truck 12 allows members to practice with the foam bucket drill. The members present are not aerial apparatus drivers, but they do ride on the truck. This is crucial knowledge for all firefighters. (Photos by author.)

(2) The vehicle height and weight label.

During this training, questions will come up and should be explored, such as the following: Where does this truck fit? What are its limitations in our first-due area and in our surrounding response areas? What does my aerial device do better or worse than my mutual-aid aerial apparatus?

First, figure out the vehicle’s height and in-service weight. The height and weight will be listed within view of the driver’s seat per NFPA 1901 as follows:

“12.1.5 The fire apparatus manufacturer shall permanently affix a high-visibility label in a location visible to the driver while seated.

“12.1.5.1 The label shall show the height of the completed unequipped fire apparatus in feet and inches (meters), the length of the completed apparatus in feet and inches (meters), and the GVWR [gross vehicle weight rating] in tons (metric tons).”

If it isn’t, inform the manufacturer and have it corrected. Regarding the in-service weight, this is different from what is posted on the placard. The GVWR is the maximum the vehicle is allowed to weigh based on the axle, tires, rim, suspension, and other vehicle components. It is important to weigh the vehicle when delivered, as NFPA 1901 advises, and yearly, as NFPA 1911, Standard for the Inspection, Maintenance, Testing, and Retirement of In-Service Emergency Vehicles, advises. To determine this weight, load the vehicle with all the equipment it will carry and follow the procedure in NFPA 1911:

“19.2.1 The fully loaded emergency vehicle shall be weighed following the procedure specified in 19.2.2 through 19.2.5 to ensure that the weight on the front and rear axles and the gross vehicle weight do not exceed the gross axle weight ratings (GAWRs) and the gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) or gross combination weight rating (GCWR) as shown on the rating plate on the emergency vehicle.”

Post the in-service weight obtained within the view of the driver so he is aware of the apparatus’ actual weight. This will assist him in identifying any bridges the new vehicle cannot go over and any overpasses or overhead obstructions that the vehicle can’t drive under. Communicate these restrictions to the drivers so everyone can plan accordingly.

Where Does It Fit?

Another overlooked preplanning item is whether the new aerial device can fit in all the firehouses. You should plan this prior to the 3 a.m. transfer/standby in the neighbor’s firehouse. The best part of this preplanning is you have to drive the vehicle to all of these places to complete it, giving the drivers plenty of wheel time and critical thinking time to get familiar with the vehicle. Although, dimensionally, the new aerial device could be similar to other current apparatus in the fleet, the driving profile and characteristics will be different. It is important that all drivers get used to this new “feel” and be comfortable with the vehicle. Complete driver training with the vehicle in both daytime and nighttime conditions. Not all emergency responses happen when it’s sunny and warm. The vehicle will drive differently at night and the aerial operations may be easier or harder, depending on how the vehicle was specified and where the lighting is located. Lighting technology changes by the year and can impact how you can use the aerial at night.

Staffing

During the specifications writing process, you defined the vehicle’s mission, which will help when you staff and train personnel to ride it. You need to ask and answer questions such as how you will staff the aerial device. The number of personnel is only part of the response; for most aerials, it should at least be four, the NFPA-recommended minimum staffing for any fire apparatus. The standard also recommends five- and six-person staffing for urban areas, high-hazard occupancies, areas with tactical hazards, a high number of incidents, or as determined by the authority having jurisdiction. Staffing of fewer than four limits the aerial crew’s ability to split up and tackle interior and exterior operations. This is a crucial part of ladder operations. With limited staffing in both career and volunteer departments, it is important to be able to complete needed tasks efficiently and safely.

Once you have the number of personnel worked out, you will need to identify the level of training you will require them to have to properly staff the apparatus. This will again fit in with the mission of the vehicle. If the aerial device carries extrication equipment, it may be a good idea to have personnel trained and certified in extrication. At the very least, members who ride the truck should understand how the aerial works. In every ladder truck I have ridden, I have made sure that the crew I rode with knew how to operate the aerial and where the override controls were. If I am stuck at a window and need help getting down, anyone on the truck should be able to make the aerial device work. They do not have to be experts, but the first time operating it should not be at 2 a.m., when the stakes are high.

A bigger question is, who brings the knowledge, expertise, and experience to the table to train the staff? The answer, most times, is someone from outside the organization. A good starting point is state or certifying aerial operator courses. They offer a good general understanding of aerial ladders and lay a solid foundation for learning. This is just a starting point. Most state classes are broad and basic. They will not provide all the necessary information to be a great operator and truly understand your vehicle.

Besides the state-level training, it is important to train and learn from the surrounding departments that also have aerial devices, to help expand your knowledge and offer more experience. Training will also help you learn and understand the strengths and weaknesses of your neighbors’ devices.

Seek subject matter experts to get intermediate and advanced training on your aerial. After all, it is one of the most expensive exposures on the fireground. Most aerials, at more than $1.8 million in today’s market, cost more than the houses we are responding to. Operators of every aerial device need a continual level of practice to obtain and maintain their proficiency, so put in place a continuing education program to review and refresh members’ knowledge.

(3) Arlington County (VA) Fire Department Tower 104 is working on waterway operations. This unit is a quint even though it is not used in that fashion; members train on its use and are familiar with pump operations.

(4) Drivers at College Park work on nighttime aerial operations. This is mandated in our driver training program, which includes both driving and operation time after sunset.

(5) The Monroe and Tuxedo (NY) Fire Departments learn the pros and cons of each other’s apparatus. Gaining this knowledge helps them work together on the fireground.

(6) Prince George’s County (MD) Fire Department Truck 9 positions on the backside of a multialarm garden apartment fire. Do not enact strict policies that restrict drivers from gaining optimal aerial positioning.

Policies and Procedures

Policies and procedures are the foundation of great departments and are needed to clarify and guide members on expectations and limitations. However, members need to understand the aerial device and its expected response area before putting policies in place. Some departments have strict policies such as, “The ladder truck shall not leave the paved surface.” Previously, I wrote how there are surfaces that builders put in place to provide for fire apparatus access but will be covered or concealed by grass.2 They offer needed access to the fire department while covering up an ugly paved road and keeping it aesthetically pleasing to the residents. Don’t put in place a policy that strict.

On the flip side, where I work in the Ballston area of Arlington County, Virginia, if you leave blacktop, you will most likely be on top of a parking garage. You should provide specific but interpretive guidance—for instance, “The ladder truck may leave the paved surface if the operator is comfortable that the surface can hold the apparatus’ weight and the vehicle can be set up and operated safely.” This leaves plenty of leeway for the operator to make an informed decision. For the department, it is incumbent on you to provide operators with training to support this procedure.

Consider also what call types it will respond on and in what priority it goes out the door. Depending on the department, you may be staffing the firehouse or the units inside the firehouse. If you staff the firehouse, there should be a set hierarchy based on the call type and location for when the aerial should leave the firehouse. Consider the height of the structure and the length of time for another aerial device to show up. Don’t forget, the aerial is not the only reason the ladder truck is being dispatched on the call. A ladder truck accomplishes specific jobs, and most other fire apparatus do not carry the ground ladders to complete that specific task. The aerial apparatus must also get the appropriate positioning for it to be effective. These are just a few of the policies you need to consider and put in place.

It is important to make time to take a step back and evaluate your aerial training. If you are expecting a new aerial device, take these questions and ensure that drivers have guidance and answers. It should not take a department getting a new aerial to evaluate its training and resources.

Endnotes

1. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2009). Two Career Fire Fighters Die after Falling From Elevated Aerial Platform – Texas. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200906.html.

2. Wilbur, Nicholas. “Aerial Ladders: How Strong Is Your Ladder Game?” (February 2020) Fire Engineering, 53-57.

NICK WILBUR is an assistant chief with the College Park (MD) Volunteer Fire Department, where he has served 14 years, nine as a master driver. He is a state certified instructor for the Maryland Fire and Rescue Institute. Wilbur has contributed to Fire Engineering on ladder placement and has been a HOT instructor at FDIC International on that topic.