BY CHRIS DALY

When asked to name the most dangerous aspects of the firefighting profession, fire chiefs and line officers can rattle off the usual suspects: truss collapse, flashover, firefighter disorientation, and a number of other hazards directly related to fireground operations. This is why we spend countless hours training firefighters to safely enter a burning structure, save any lives in jeopardy, and place the fire under control. Our actions on the fireground may save the very person who started the fire, making us the heroes for the day. After the fire, the firefighters and the fire officers return to their stations, never realizing the innocent lives that may have been put at risk while they were driving to or from that same call.

Our Lethal Weapon

A speeding fire apparatus is a lethal weapon. Each day across our country, thousands of fire departments load a speeding bullet with trained firefighters and send it hurtling across the district that they have sworn to protect. Although this bullet usually makes it safely to the scene, sometimes a successful response occurs by pure luck. Unfortunately, the one time that the bullet fails to make it safely to the scene, the fire service is on the front page nationwide with a photo of an upside-down fire truck and an obliterated car by the wayside.

Each year, we preach about the countless firefighters who were killed or injured while responding to a call, but what about the other person? How many civilian lives have we destroyed with our reckless behavior while responding? How often has a fire officer held a driver accountable for his actions behind the wheel? It seems that as long as we arrive on scene before the other responders, no one will say a word to the reckless fire apparatus operator. So, this irresponsible behavior continues.

When I first started teaching fire apparatus vehicle operations and crash avoidance, I made it a point not to offend fire departments that held the fastest drivers in the highest regard. However, the more unnecessary fire apparatus crashes I saw in the news, the more annoyed I became; eventually, my filter came off. Some fire apparatus operators need to grow up and act like professionals sworn to save lives, not take them.

(1) Understanding lateral g-force enables fire apparatus operators to fully understand how and why they can lose control of a fire apparatus. The ability to judge how much g-force a vehicle will experience while rounding a curve and how this g-force can cause a crash will create safer drivers. (Photos by author.)

Are you getting angry? Good. Quite frankly, if you are getting angry reading this article, I want to reach you. If you are nodding your head in agreement, I want to speak to you as well.

Training and Discipline

Over the past 15 years of teaching the “Drive to Survive” program, I’ve often been asked, “How do we solve the problem of firefighters racing to the scene, always trying to beat the other responders in?” My answer: “Training and discipline.” Fire apparatus operators must learn to recognize the hazards of driving a 40,000-pound fire apparatus at 50 miles per hour (mph) through rush-hour traffic. Until fire apparatus operators learn to respect the dangerous weapon they hold in their hands, few will modify their driving habits.

As a police officer, I carry a loaded gun at all times. I am trained to take it from my holster and point it only at someone who is threatening to take someone’s life. I would never consider taking my weapon out for no reason and waving it around on a busy street corner. If I did, I would probably be fired. However, fire apparatus operators still keep driving their vehicles recklessly and unsafely, which is no different from waving a loaded gun on a crowded corner. Yet, very seldom is anyone disciplined for it because of the culture we live in. This has to change. Fire apparatus operators must be held accountable for their actions and be trained to respect the power they hold in their hands to destroy lives every time they get behind the wheel.

Better Training

How do we change our culture? The first issue is training. For those familiar with driver training, the most common class is the emergency vehicle operator course (EVOC). It is a good start, but what does your EVOC really teach the student? Does it address the most common causes of serious fire apparatus crashes, such as high-speed driving, failing to negotiate curves, rollovers, and intersection collisions? Or, is it simply a day spent driving around cones at five mph in a parking lot so you can check off a few boxes and tell the bosses that you “did it”? Although practicing low-speed precision maneuvers in a cone course is valuable, how does this relate to an actual emergency response at highway speed?

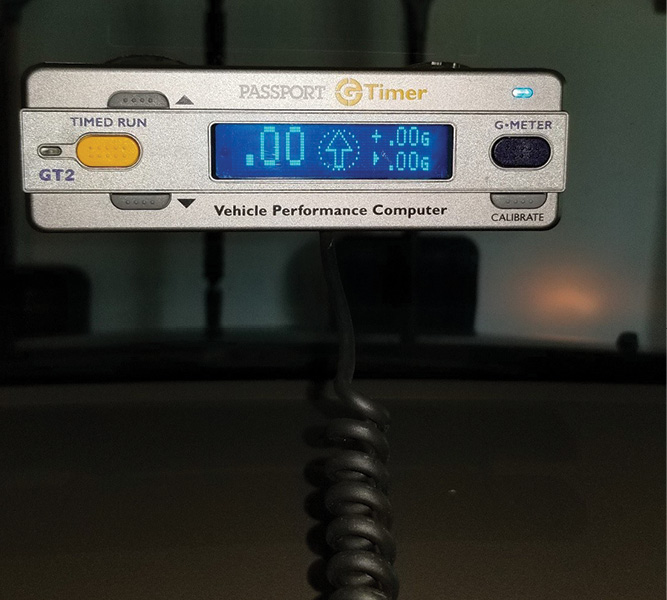

(2) A simple g-meter will allow the fire apparatus operator to better understand the increase and decrease in g-force that acts on the vehicle as a result of speed and turn radius. These meters should not only be used for training but also be installed on all vehicles to improve overall vehicle safety.

We must completely rethink how we train our firefighters in emergency vehicle operations. Those who oversee driver training must consider the low-speed precision driving skills learned on a traditional cone course and the more advanced topics that pertain to real-life emergency responses at highway speed. We should incorporate both of these modalities into a comprehensive driver training program that meets all the relevant National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards such as NFPA 1451, Standard for a Fire and Emergency Service Vehicle Operations Training Program; NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety, Health, and Wellness Program; and NFPA 1002, Standard for Fire Apparatus Driver/Operator Professional Qualifications.

We can reinvent EVOC first by identifying how and why our serious crashes are occurring. Most serious crashes result from our drivers’ failure to appreciate the advanced vehicle dynamics that lead to a crash. As a result, an operator may overdrive the vehicle’s capabilities and crash. In addition, many drivers do not understand the limits of our emergency warning devices, and so they unsafely navigate an intersection and collide with a civilian vehicle.

Curve dynamics and intersection dangers are the two most common causes of serious fire apparatus crashes. Therefore, as professional fire apparatus operators and driver trainers, we must rectify these problems.

Curve Crash

Three words commonly used to discuss driving through a curve are inertia, centrifugal force, and momentum. The concept of inertia means that an object in motion will stay in motion unless acted on by another force. But how does inertia cause a fire apparatus to crash? Can one driver better control inertia than another? If a driver thinks he is “really good,” can’t he overcome the “normal” issues related to inertia? No, and it is important for us to teach this.

The easiest way to teach firefighters why fire trucks roll over or crash in curves is to teach the concept of lateral g-force. Anyone who has seen the movie Top Gun or has any knowledge of auto racing has heard of g-force. Because it is such a common term, it will help make the fire apparatus crash issue more understandable for students.

The amount of lateral g-force that a vehicle will experience while rounding a curve is directly related to the speed of the vehicle and how sharply the driver turns the wheel. By teaching these concepts in understandable terms, fire apparatus operators will be able to understand that they have sole control over how much lateral g-force they place on the vehicle. If they place too much lateral g-force on the vehicle, it will roll over or slide off the road. Understanding lateral g-force also helps a fire apparatus operator to better appreciate the hazards of speeding, unsafe braking, driving in inclement weather, and countless other causative factors associated with an emergency vehicle crash.

The concept of lateral g-force can be taught in a few hours in a classroom, followed by an exercise using a g-force meter obtained from the Internet. After learning about lateral g-force and how much of it is unsafe, a driver trainee would participate in a fire apparatus driving exercise. The g-force meter is mounted in the center of the windshield; the driver trainee is seated in the passenger seat. As another drives, the trainee sees for himself how the g-force increases and decreases, depending on how the vehicle is operated, and how easy it is to approach an unsafe level of driving.

(3) A hands-on demonstration can illustrate to fire apparatus operators the limited range of their emergency warning devices and why they need to come to a complete stop when negotiating a negative right-of-way intersection. Here, sound level meters are measuring the volume of the siren at different distances.

More importantly, the use of a g-meter will allow the trainees to better appreciate the effect of the g-force they will feel on their body. Teaching driver trainees how to relate the sensation of g-force to an actual number, the driver trainees will learn to “fly by the seat of their pants,” just as World War II fighter pilots learned to safely fly their planes without using instruments. Understanding what it feels like when a vehicle is being operated unsafely is an important learning tool that will allow drivers to recognize when they are starting to push the envelope and need to slow down.

Some of us remember when we used the top of our ears to determine when to leave a fire room. Although this crude warning device has sent many of us to the emergency room, it kept many firefighters from being caught in a flashover. The same concept holds true with fire apparatus operators. By understanding how it feels on your body as g-force increases or decreases, the driver trainees will learn when to back off on the accelerator or the steering wheel as driving conditions start to become unsafe.

Intersections and Warning Devices

Fire apparatus often crash or roll over on curves; these crashes typically result in serious firefighter injuries or fatalities. Unfortunately, there are also situations when a fire apparatus crash kills a civilian, typically at an intersection. This is the result of an emergency vehicle operator’s failing to stop at a negative right-of-way intersection or to give proper “notice of approach.”

Few fire department driver training programs provide detailed information on the limitations of audible warning devices (sirens). As a result, fire apparatus operators often overestimate the effective range of the siren. Countless studies have shown that the effective range of a siren at an urban intersection can be as little as 40 feet. If the fire apparatus operator fails to understand the effects of this limited siren range, a serious intersection crash can result. Driver training programs must explain in detail why sirens are no longer effective with today’s modern automobiles, including hands-on demonstrations using emergency sirens and a calibrated sound pressure meter. Demonstrating the siren’s limited range will give emergency vehicle operators a better understanding of why they must come to a complete stop at a negative right-of-way intersection.

Emergency vehicle crashes have many causes. However, the two issues addressed in this article often result in injuries or fatalities to firefighters and civilians. As such, we must seek ways to reinvent our EVOC programs and ensure that fire apparatus operators have a more thorough understanding of lateral g-force and intersection safety. Low-speed precision training in a cone course may be helpful in reducing property damage crashes, but it does not adequately address the causative factors of the serious crashes that result in injuries or fatalities.

Reinventing our EVOC programs will cost money. But the amount spent on driver training will pale in comparison to that spent on workers’ compensation claims, lawsuits, and apparatus repairs that accompany a serious emergency vehicle crash.

By reinventing our driver training programs, we can create more “bulletproof” drivers who will understand the importance of vehicle operations. Bulletproof drivers will be better able to prevent a serious fire apparatus crash and also be better protected in the legal world should a fire department be sued when a crash occurs.

References

Daly, Chris. “Siren Limitation Training.” Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment, April 2017, 32. https://bit.ly/2Ab6sNt.

Daly, Chris. “Apparatus Siren Limitations and Intersection Crashes.” Fire Engineering. February 2017, 54. https://bit.ly/2UWpqAt.

CHRIS DALY developed the “Drive to Survive” emergency vehicle driver training program. He is an accredited crash reconstructionist and a lead investigator for the Chester County (PA) Serious Crash Assistance Team. A contributor to Fire Engineering and Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment, Daly has served as a firefighter and a police officer. He will teach “Drive to Survive” at FDIC International 2019.