BY JEFF ROTHMEIER

Mastery in any domain requires a certain disposition—one that is intentional, willing, and resilient. The pursuit of firefighting excellence is no different. However, it bears burdens that tax the extreme ends of human capabilities. Firefighters work in conditions that are untenable while wearing equipment that rapidly declines in physical performance in a time-compressed, inherently dangerous environment. They also face some of the most heart-wrenching moral scenarios and must metabolize trauma effectively to avoid the emotional struggles associated with such exposures. In addition, they must make decisions rapidly, often with incomplete information, and fully commit to executing those actions regardless of the degree of accuracy.

- Warfighting for Firefighters

- The Art of War for Firefighting

- Wargaming for the Fire Service: Fight a Fire Every Day

Fire combat is physically, mentally, and morally challenging. Achieving objectives in such an environment begins with a disposition that seeks to win at all costs. A company or department whose motive is excellence has already taken the critical first step in overcoming the obstacles in a fire attack. The layout, force, and other initial engagement activities will be as fluid as a no-huddle offense on its first drive of the game. A disposition that is action-biased by well-trained firefighters can absorb the first few friction points of the emergency scene. Such a disposition can overcome obstacles with vigor and continuously move responders forward to their objective. The disposition that is critical in every facet of the fire attack is the individual’s and the unit’s will to fight (WF).

The WF can be beneficial in the station, in the gym, or on the drill ground. It impacts firefighters’ preparation phase. The WF is instilled and enforced in units whose members routinely engage in warrior tasks, physical fitness, and mental preparation. A high degree of WF is built from the discipline of habitual conditioning. The habits are an indication that a unit finds it rewarding to sacrifice for success. On the fireground, it enables a unit to tolerate much more friction from fireground conditions. The members have prepared themselves for adversity and have developed the prerequisite adaptive/initiative-laden behaviors to overcome obstacles. Such a positive adaptive response to adversity exemplifies resilience.

The fire service’s mission is to save lives and property (photos 1 and 2). Achieving this objective often endangers the safety of the responders. The uncertainties and dangers of firefighting have led to firefighting being perceived as a form of combat. Firefighting conditioning, therefore, must include components that will increase the chances of optimal outcomes.

1. Firefighters attack an upper-level fire. (Photos courtesy of Scott Carnahan.)

2. Firefighters execute a peaked-roof ventilation tactic.

The Rand Corporation Study

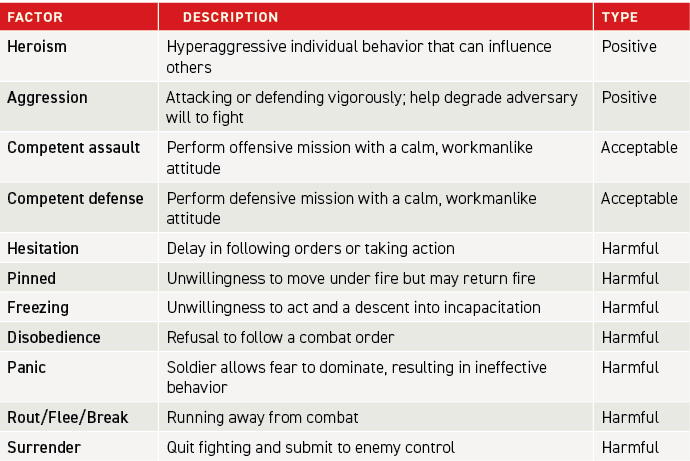

The United States Army hired the Rand Corporation in 2018 to study the influence of the moral factor WF in war. The objective was to determine the influence of WF on combat outcomes: how it is identified on the battlefield; how it is demonstrated in an individual, in a small unit, and on a national level; and its characteristics. Figure 1 illustrates the effects of soldiers’ various dispositions on the battleground.

Rand identified WF as “the disposition and decision to fight, act, or persevere as needed.” Rand noted in its report:

Arguably, will to fight is the single most important factor in war. Will to fight is the disposition and decision to fight, to keep fighting, and to win. The best technology in the world is useless without the force of will to use it and to keep using it even as casualties mount and unexpected calamities arise. Will to fight represents the indelibly human nature of warfare.

In addition, Rand found that the effectiveness of the individual and the unit depended on their dispositions and that the national government was determined to conduct sustained military and other operations for an objective, even when the expectation of success decreased or the need for significant political, economic, and military sacrifice increased.

Figure 1. Possible Combat Behaviors Resulting from Decisions Driven by the Will to Fight

Assault generally requires a greater will to fight than defense.

Source: Rand Corporation study, 2018.

Fire Department Culture and Will to Fight

Following are some of the ways WF is manifested in a fire department:

- The degree to which members support victim-focused tactics on the fireground.

- Observing the six-minute survival window for victims.

- Forgoing a water supply before advancing an interior attack line.

- Beginning search operations before the fire is completely extinguished.

- Conducting searches and vents before rapid intervention teams (RITs) are dedicated.

Water supplies and RITs are valuable assets on the fireground. Conducting safety-focused operations at the expense of securing the first objective (victim life safety) seems at odds with our mission statement and oath. The fact remains that when we dedicate time and resources to these safety-focused tactics before completing base extinguishment, primary searches, and ventilating structures, we have not shaped a tenable environment for the citizens in their six-minute survival window. Essentially, our operation will be combat ineffective. Our duty is to become combat-effective given the realities waging havoc on those we serve.

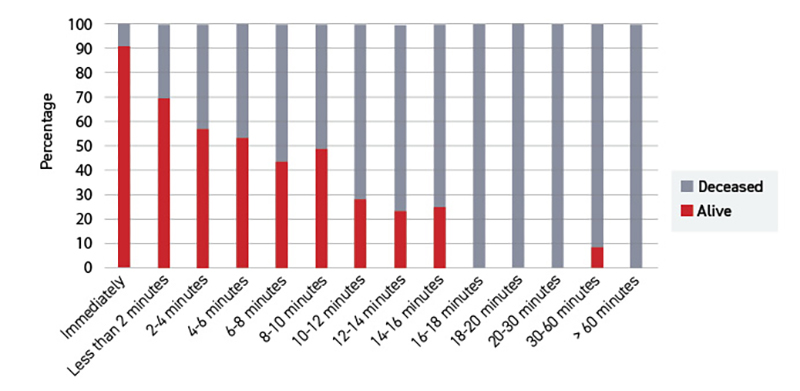

Often, cultures in the fire service value safety-focused tactics over victim-focused tactics. These cultures are more passive in their disposition to ensure life safety and display a waning WF. Departments that encounter victims regularly have been conditioned to be less conservative in managing risk. Managing risk is the business of the fire service. If the only gain is a safe outcome for firefighters, we fail to meet the tenets of the fire service. WF must be enhanced in the department that expects to save lives (Figures 2-4).

Figure 2. Victim Outcomes Based on the Time Until First Responders Found Them in the Structure

Source: Firefighter Rescue Survey.

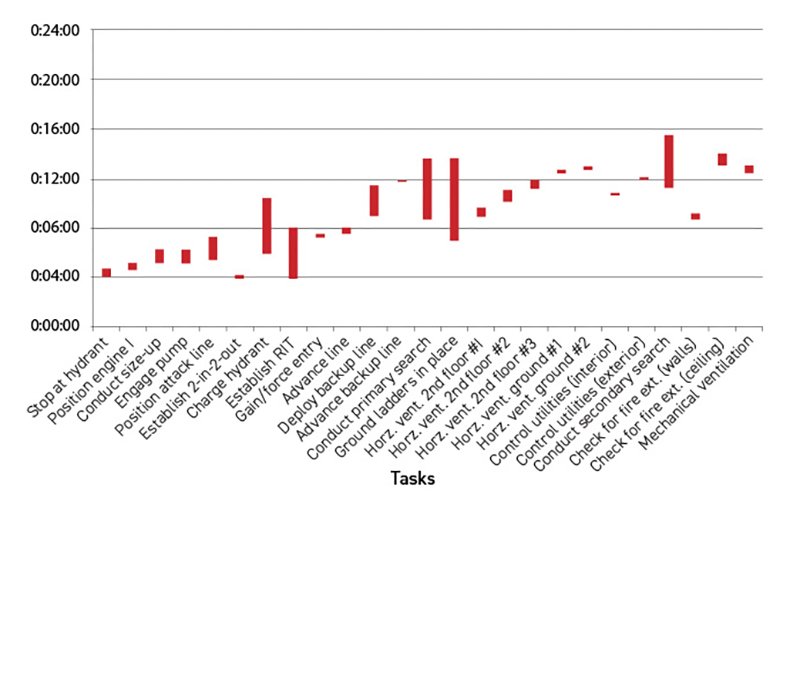

Figure 3. NIST Study on Effect of Crew Size on the Fireground

Source: The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Report on Residential Fireground Field Experiments, NIST Technical Note 1661.

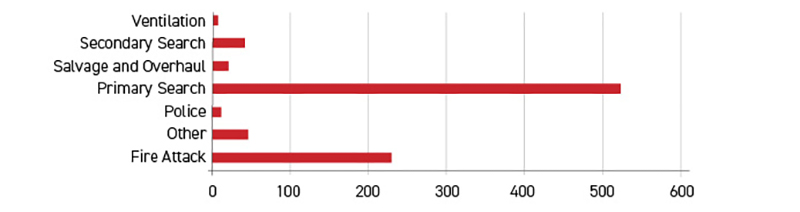

Figure 4. Tactical Assignment Finding Victims

Data from the 2020 Firefighter Rescue Survey shows the tactical assignment firefighters were executing when they found victims. Primary search needs to be prioritized immediately to ensure victim rescue. Source: Firefighter Rescue Survey.

Rand sought to analyze the differences in strategies and tactics deployed in various dispositions influencing combat outcomes. Those questions could be applied similarly to the fire service in the following ways: What is the impact on emergencies that have the potential to harm citizens if the unit’s or department’s will to fight is inadequate? Are firefighters impacted beyond the risks of the scene if they are conditioned in a manner that results in a less-than-capable disposition to the scene’s demands?

Resilience

Another way to define WF is resilience. In The Psychology of Sport and Exercise, Fletcher and Sarkar define resilience as a “dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity.” In Child Development, Luthar, Cicchetti, and Becker describe it as “the positive role of individual differences in people’s response to stress and adversity.”1, 2

There is no disputing the degree of adversity firefighters face on emergency scenes and that resilience is a necessary trait for our crews, departments, and responders.

Resilience empowers firefighters to continue their efforts under duress through positive adaptation. One form of positive adaptation is initiative. We could characterize firefighters’ feeding off each other’s initiative as cohesion. Initiative and cohesion are factors that can have a positive effect in adverse conditions. They also are counterweights for the morale stress combat creates and they allow us to accomplish our desired goals.

Initiative and cohesion are moral factors that counterbalance menace and uncertainty. John Boyd, who conceptualized Patterns of Conflict, trained our nation’s military leaders in the post-Vietnam era in how to be more effective in combat. A consideration that arose from those educational settings centered on the following questions:3

- Did the U.S. military ever consider the resolve—WF of the Vietnamese enemy and of the United States—factors to be overcome?

- How long would our nation support the conflict, and does that moral support show its presence in some form on the battlefield?

- Did either side have a WF that influenced combat outcomes? Did simply counting our casualty numbers vs. those of the enemy predict the outcome?

- Did estimating our volume of tanks, aircraft, and munitions give us a reliable indicator of our power over the enemy?

It would seem that such measurable assets would provide information that would help to calculate combat potential; but, as we now know, they don’t ensure combat success. How we define the mission and, more importantly, how we think about it have much more to do with obtaining combat-effective outcomes.

Surely, the argument would have centered around the might and numbers of the U.S. military. The effectiveness of our military against such an outmatched opponent was beyond question—or was it?

Shortly after the Vietnam War, Boyd gave his presentations to military leaders, who were seeking answers. The United States Marine Corps also had questions and adopted a new philosophy relative to their combat operations. They adopted Marine Corps Doctrine Publication 1, Warfighting, in their curriculum as a guide for how the Marines should think about combat. They also implemented a strategy for combat called “Maneuver Warfare,” which uses many of the moral components described in Boyd’s lectures.

Competence is another component of WF. When critiquing operations in fire departments, a breakdown in competence often is identified as the reason the teams were not as efficient as they should have been.

Will to Fight and Outcomes in Combat Models

Rand research showed that when factoring WF in its combat models, the outcomes changed, sometimes drastically. WF had the greatest influence at the times of state changes, the times when stress accumulated unexpectedly, and decisions were forced.4 An example of conditions warranting a state change on the fireground would be the scenario in which the line is advanced, the fire is not found, and the engine crew is deep in the structure with zero visibility and rapidly increasing heat. Does the engine continue to look for and attack the fire? Another example would be searching above the fire, reaching the second bedroom, losing all visibility, and experiencing a significant increase in heat. Does the search team continue the search?

These decisions are heavily influenced by the members’ or the unit’s disposition (photo 3). The disposition that has been conditioned by a department’s culture will prevail. Changes in the state of the event cause behavior changes, and behaviors are conditioned through culture, training, experience, and other values of the operators.

Human Factors in Combat

Rand’s findings suggest that combat is a human endeavor; therefore, human factors must be considered. WF (resilience) is a significant human factor when faced with a strong adversary or adversity. Winning at the tactical level hinges on WF. 4

Along with resources, technology, tactics, or other factors, the human will is of primary importance in combat. How we condition the will of a department, company, or individual determines how we will approach saving lives. Sustaining a fighting unit’s resilience amid the frictions of the fireground is no small matter. The key to victory is the human will to adapt and overcome in the face of adversity. The fire service should focus on the factors that constitute this trait and enforce the principles that help to develop it.

What traits correlate with effective outcomes? In leadership coursework, we discuss the traits a leader must develop. The same process can be used to build WF. The factors associated with WF are many. Following are a few factors that my research has shown have the greatest effect on WF for individuals, small units, and the nation.

Character

An essential component of our profession, character is demonstrated by discipline and sacrifice, which are selfless behaviors. They affect not only individuals but have a ripple effect throughout an organization.

Be humble, not entitled. Consider the behavior of entitlement. Often in the fire service, seniority garners privileges. This construct far too often is abused and is at odds with selflessness. Resentment in the presence of entitlement can build at worst; often in the best-case scenario, more entitlement is manifested from the repeated examples a culture tolerates. Acting out of good nature with grace and humility is rooted in virtue that secures justice, trust, and cohesion.

If you are the senior person whose skill sets are above that of the crew, they will already know it. Behaving in a manner that exploits it for the sake of ego does nothing but erode the company’s character. Having seniority is also a known entity in the house. We live together; everyone knows who and what each brings to the table. We can boost the collective morale of our station if we don’t feel the need to comfort ourselves through entitled-type behaviors. In this way, the crew may be inspired to train more and follow your example. They may find ways to learn from your selfless behavior throughout the shift, and the collective WF will be enhanced.

The most powerful lesson I learned about building character was from a veteran who served in Iwo Jima, a member of the Greatest Generation. When I asked him why his generation commonly acted with the values of integrity, personal responsibility, honesty, and work ethic, his answer was short but poignant. He said there were so many examples around him that he couldn’t help but follow suit. We are creatures of our environment and often mimic behaviors out of pure social survival, especially in the firehouse. Every member of an organization can exhibits leadership behaviors. We can all decipher selfless behaviors and know how to lessen the burdens of our brothers and sisters.

3. Firefighters confronting the friction of the fireground.

Be courageous and consistent. We must have the courage to do the right thing consistently, even when we know the decision will be criticized or viewed negatively by others because it does not measure up to the cultural wall of normalcy. We must set an example for others to follow. Acting with character becomes infectious to those aspiring to be a part of a brotherhood. The actions can be small, but they must be daily. In our house, when members of one rig are toned out for a fire during lunch, the remaining members cover their food with foil or plastic wrap. Other examples include catching the door for firefighters on the way back to the rig, so they have less to manage when carrying equipment and carrying out some of the equipment for the rest of the crew once it’s deemed unnecessary. A burden spread out among the members is recognized. Entitlement is at odds with these tactics that encourage cohesion.

Competence

When we can withstand friction and uncertainty, we’re showing competence; it is a hard-earned reality that requires a high degree of discipline. Motivation levels must be high for the unit or firefighter who has this trait. Curiosity is the most valuable trait for those who want to enhance their WF. Motivation and a heavy dose of curiosity will enable crews to forge a path toward mastery. Since fireground tasks require heavy energy burdens, training also taxes the system, hence the value of motivation. A competent unit is synonymous with an adaptable unit. It also displays initiative. Confidence is born from the ability to perform, which initiates, at the very least, a workmanlike disposition and an aggressive behavior.

Competence must be continuously developed. Training at the academy is not enough. The skills must continually be worked on and must be relevant—those skills that are carried out on the fireground.

Competence is also leaning on experience. Pattern recognition doesn’t occur without experience and is challenging to develop without being on the battlefield. After-action reviews and mentorship can bridge that gap. How willing are your members to habitually engage in these investment behaviors? You must believe in the mission and its relevance to you. The disposition that empowers actions is beholding the proper philosophy.

The decisions that will lead to combat-effective or -ineffective outcomes are not products of chance. Deciding to pursue character and competence increases WF. Pursuing other interests in this craft leaves to chance the variable outcomes found toward the bottom of the table. These are combat behaviors we have all seen in some form on the fireground.

ENDNOTES

1. Fletcher, D. and Mustafa Sarkar, “A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions,” Psychology of Sport and Exercise, September 2012. bit.ly/4bkVHZc.

2. Luthar, Suniya S., Danti Cicchetti, Bronwyn Becker, “The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work,” Child Development, National Library of Medicine, 2003. bit.ly/42rcyFt.

3. Boyd, John, Patterns of Conflict, Project White Horse, 2007. bit.ly/4beJQf3.

4. Connable, Ben, Michael J. McNerney, William Marcellino, Aaron B. Frank, Henry Hargrove, Marek N. Posard, S. Rebecca Zimmerman, et al, Will to Fight: Analyzing, Modeling, and Simulating the Will to Fight of Military Units, Rand Corporation, 2018. bit.ly/47YMkeF.

JEFF ROTHMEIER, an 18-year veteran of the fire service, is a member of Rescue 1 in the Milwaukee (WI) Fire Department. Previously, he served nearly 13 years with the Saint Paul (MN) Fire Department, where he was a company officer. He is a former member of the Minnesota Aviation Rescue Team and of the Minnesota Task Force 1 State Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) and collapsed structure team. He has an associate of applied science degree in fire science technology, a bachelor’s degree in fire and emergency response management, and a graduate degree in organizational change leadership. A decorated combat veteran, he the author of Mastering the Craft: Cultivating a Philosophy for Fire Attack (Fire Engineering) and an author for Fire Engineering.

Jeff Rothmeier will present “Cultivating Aggression: The Lost Art of Fire Combat” at FDIC International in Indianapolis, Indiana, on Tuesday, April 16, 2024, 8 a.m.-12 p.m.