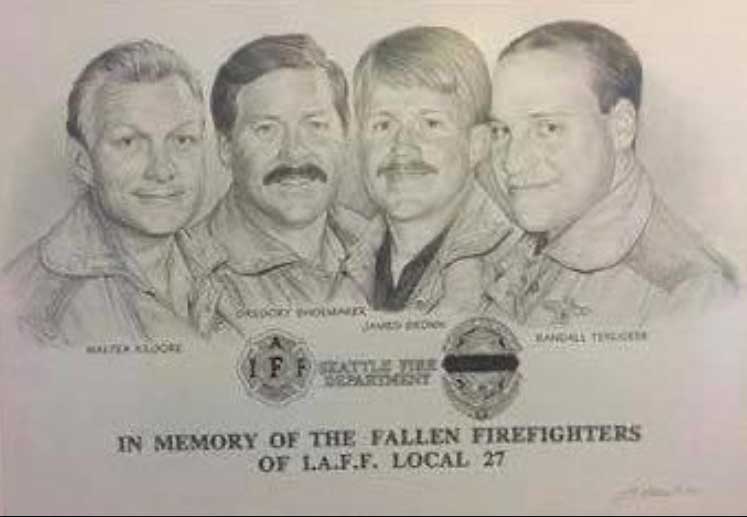

On January 5, 1995, four Seattle (WA) firefighters were killed in an arson at the Mary Pang Food Products Warehouse.

The fire claimed the lives of Lieutenant Walt Kilgore, Lieutenant Greg Shoemaker, Firefighter James Brown, and Firefighter Randy Terlicker, when members fell through the floor into the fiery basement of the building. As noted by Frank Brannigan, the building had been modified with additions that firefighters were unaware of at the time.

Martin Pang, son of the owners of Mary Pang Food Products, was sentenced to prison in the case.

- Brannigan: Hidden Fire and Collapse

- Belowgrade Fires: Firefighter Traps

- Keep It All in Perspective, Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

From the U.S. Fire Administration Report: J. Gordon Routley

Four firefighters died when a floor collapsed without warning during a commercial building fire in downtown Seattle on January 5, 1995. The cause of the fire was determined to be arson, and a suspect was apprehended and charged with four counts of homicide.

The circumstances of this incident are similar to a number of other multiple fatality incidents that have claimed the lives of more than 20 firefighters in recent memory across the nation (Brackenridge and Pittston, Pennsylvania; 12 New York City firefighters died in a similar incident in 1966).

The similarities include fires in buildings that have access at different levels from different sides, resulting in confusion over the levels where companies are operating. There have also been a number of situations where firefighters have been operating on a floor level that appeared to be safe, not knowing that they were directly above a serious basement or lower level fire. These incidents resulted in sudden and unanticipated floor collapses, which either dropped the firefighters into the fire area or exposed them to an eruption of fire from the level below them.

The structure involved in this incident was primarily constructed of heavy timber members. However, a modification to the structure had resulted in the main floor being supported by an unprotected wood frame “pony wall” along one side. The sudden failure of this support caused the main floor to collapse without warning. Firefighters working on this floor believed that they had already gained control of the situation and were not aware that the main body of fire was directly below them or that it was exposing a vulnerable element of the structural support system.

This situation illustrates that multiple firefighter fatalities can occur at an incident where fire suppression operations are well organized, well managed, and well executed with a strong emphasis on operational safety. One of the important lessons that comes from this event should be valuable to both new and experienced fire officers; it shows how critical information can be missed during a complicated incident command operation, particularly when command officers are distracted by trying to perform too many functions without support staff.

Description of the Structure

The Mary Pang Chinese Food Company occupied a building in Seattle’s International District at 815 Seventh Avenue South, a few blocks from the Kingdome. The company prepared frozen Chinese food dishes for distribution to grocery stores in the Seattle area and had been operating from the same location for more than 20 years. A bakery that supplied retail outlets in the Seattle area occupied part of the lower level, and an unused warehouse space was rented out as an evening practice area for a rock band.

The building was constructed in stages and had been modified several times over its history of more than 85 years. The occupancy is also believed to have changed several times. The resulting structure was very difficult to interpret from the exterior. The history of the building was obtained through a number of records and plans, dating back to 1909; however, many of the details are uncertain, particularly with respect to the dates and sequence of modifications.

History

The oldest part of the Mary Pang building was constructed as a single-story structure, 60 x 60 feet in area, with brick exterior walls and wood posts supporting a wood roof. In subsequent years two additional sections, also 60 x 60 feet in area, were added north and west of the original structure to form an L-shaped building. When the two sections were added, two of the brick walls of the original structure became interior fire walls. Over the years several doorways and windows were bricked-over and the connections between sections were modified several times.

When the original structure was built it was in a low-lying swampy area, south of the downtown business district. During the 1920’s a major project was undertaken to raise the ground level in this part of Seattle. A large hill north of downtown was removed and the fill was used to raise the level of the low-lying area to the south. The streets in this area were raised by 10 to 20 feet and the ground floors of many buildings became basements.

At the comer of Seventh Avenue South and Charles Street the new grade level of the streets was higher than the roofs of the single-story structures, which were now located in the low-lying area between the raised streets. The east wall of the original structure was reconstructed as a retaining wall and increased in height by approximately five feet to hold back the fill that was used to raise the level of Seventh Avenue South. The south wall of this section was partially buried, covering several of window openings. The original ground floor level became a windowless basement, accessible only through the north and west wings.

When the elevation of the streets was raised, the roof of the original 60 x 60 foot structure was removed and an upper story was added, with the new floor at the same level as the sidewalk on Seventh Avenue South. The new story was post and beam construction, with large dimension wood members supporting the new floor and roof. It was built with three wood frame exterior walls and a brick wall on the south side. The large mass of the wood structural members made them inherently fire resistant – they will burn and eventually collapse, but they can be expected to maintain their structural integrity for an extended period of time.

The hidden flaw in the structure was the support for the ends of the new floor joists along the north wall. The original roof was supported by a ledge that was incorporated in the brick wall. Because the new floor was four to five feet higher than the roof, a wood frame “pony wall” was fabricated from 2 x 4 inch wood members and erected on top of the ledge to support the ends of the new floor joists. This assembly did not have the inherent fire resistance of the more massive wood members and could be expected to fail rapidly under fire conditions. The failure of this assembly would release the ends of the floor joists and result in a sudden floor collapse.

An upper level was added to the north wing at a later date and the original brick wall between the sections was extended upward to create a fire separation between the upper stories. The original wood frame wall of the upper story was left in place.

Over the years several changes were made in the structure to meet the needs of different owners and occupants. This included the addition of a concrete topping over the wood floor to meet health standards for a food preparation facility. At the same time, the interior stairway was permanently covered-over with a wood and concrete deck, leaving no interior communication between the upper and lower levels. A small lunch room was also added adjacent to the north wall, above the west wing.

At the time of the fire the north wing and the original (center) section, which faced Seventh Avenue South, had one story above grade level and one story below grade. The west wing remained as a single story structure attached to the lower level of the center section. The three sections were separated by interior brick walls; however, there were openings between the sections at each level.

Fire Discovery

The fire was set in the storage room shortly before 1900 hours on Thursday evening, January 5, 1995. It quickly grew to major proportions within the storage room and burned through the wood frame partition into the area occupied by the bakery. It also burned through the metal clad wood frame section that covered the gap in the west wall, between the top* of the brick and the underside of the upper floor deck. The fire then lapped up the exterior of the metal covered wall, above the roof of the west wing.

The first call to the Seattle Fire Department was received at 1902 hours from a member of the band, reporting that smoke was coming into their practice area from the adjoining section of the building. This was quickly followed by other callers reporting a working structure fire in the area of Maynard Avenue South and South Dearborn Street. A full first alarm assignment, consisting of five engine companies, two ladder companies, one BLS ambulance, one paramedic unit, an air supply unit, and two command officers was dispatched at 1903 hours.

Companies approaching the scene saw a large column of smoke in the air. The wind was calm and the smoke column was rising almost vertically above the fire. The first arriving company, Engine 10, responded to the intersection of Maynard and Dearborn, then proceeded south on Maynard to South Charles Street. From this vantage point a heavy volume of fire could be seen above the roof of the west wing of the building. The fire appeared to be burning against the exterior of the rear (west) wall of the center section and threatening to penetrate into the structure.

As Engine 10 passed to the south of the building along South Charles Street, some of the crew members noted that the main body of fire appeared to be coming from a small shed that extended out from the wall, above the roof of the west wing. (This was a lunch room that had been added at the rear of the upper level.) They believed that the fire could be coming from this shed and extending to the main structure. Engine 10 proceeded around to the east side, which was the front of the building.

Initial Actions

Engine 10 reported on the scene with a “well-involved building fire” and assumed command at 1907 hours. The Lieutenant’s report indicated that Engine 10 would be “laying a l-1/2 inch manifold.” Engine 10 hookedup to the hydrant at the northeast comer of Seventh Avenue South and South Charles Street and extended a 3-inch line to the manifold, which was placed at the southwest comer. Several attack lines can be taken from the manifold.

Ladder 1 followed Engine 10 into the scene and spotted on the east side of the building near the mid-point. The Lieutenant in charge of Ladder 1 conferred with the Lieutenant of Engine 10 while the crew initiated forcible entry. The crew was then directed to raise ground ladders and proceed to the roof to perform vertical ventilation.

The Acting Deputy Chief, who was assigned as the Shift Commander (Battalion 1) arrived approximately one minute behind Engine 10. The Battalion 1 vehicle was positioned on South Charles Street near the rear driveway entrance to establish a Command Post. The Acting Deputy Chief walked to the intersection to confer with the Lieutenant of Engine 10 while his aide set up the command post. He agreed with the Lieutenant’s assessment of the situation and approved the attack plan, which was an interior attack from east to west to keep the exterior fire from extending into the building.

The Acting Deputy Chief then announced that he would be assuming command on the Charles Street side of the fire. His initial report was “Fire in a two-story, 50 x 80 ft building. Engine 5 will be operating on the exterior only from the rear. Engine 10 will be attacking through the interior from the opposite side. Battalion 1 will be Charles Command.” The Lieutenant of Engine 10 was designated as Division B and assigned to supervise the companies on the east side of the fire.

The Incident Commander then assigned Engine 5 to the west side with specific instructions to prevent exterior spread of the fire, but not to make a direct attack from the west because the interior crews would be working from east to west. Engine 5 placed their manifold at the west driveway and stretched a 3-inch line to the hydrant at the southwest comer of Seventh Avenue South and South Charles Street.

Engine 13 was assigned to work with Engine 10 on the interior attack from the east side. The Lieutenant of Engine 10 assigned two of his crew members to work under the Lieutenant from Engine 13, while he continued to direct operations from the outside. Two l-3/4 inch attack lines were advanced through the roll-up door into the south half of the building, one by Engine 13 and one by the crew members from Engine 10.

Engine 2 was assigned to work with Engine 5 on the west side. The Captain in charge of Engine 2 was designated as Division C and assigned to supervise the companies on the west side of the building.

Battalion Chief 5 arrived and was assigned to relieve the Lieutenant of Engine 10 as Division B. The Lieutenant and another crew member from Engine 10 then took a third line into the building through the office door.

Engine 36 reported to the Command Post and was assigned to report to Division B. They were directed to take another attack line through a door into the north half of the building to check for extension.

Ladder 3 approached from the east on South Dearborn Street and viewed the fire from the north. The Captain decided to place the ladder truck in the parking lot to the north of the fire building and to ladder the north wing. The crew then went to the roof with ventilation equipment.

The Incident Commander requested two additional engine companies and one more ladder company to respond at 1910 hours and directed the incoming units to establish a Base at South Charles and Maynard. Four minutes later he upgraded the request to a full second alarm.

Interior Operations

The first two attack lines were advanced into the building by the crews of Engines 10 and 13. They found the interior to be hot and heavily charged with smoke, but did not encounter any major interior fire involvement. A few spot fires were found and immediately knocked down with bursts of water from the hose lines. Most of the spot fires were reported to be near the floor level.

The crew advancing the third line encountered similar conditions as they worked their way through the interior. One spot fire was found near the floor level in the office area and others were found toward the rear. Some fire was also observed and extinguished on the underside of the roof.

The crews were working in zero visibility conditions and had to advance slowly, moving around equipment and stored materials inside the building. They reported that the interior temperatures were hot enough to keep them crouched down, but not hot enough to cause unusual concern.

The three attack teams used up their air supplies and rotated out to change air cylinders. The attack lines were backed-out to the doorways where they were picked-up by fresh teams and teams that had already exchanged their cylinders. Each team entering or leaving the building reported to Battalion Chief 5, who was maintaining the accountability system for Division B.

Engine 36 worked their way through the north wing, from east to west and encountered only one small spot fire. (This was near a small breach in the fire wall where the fire had communicated through from the basement.) They reported to Division B that there was no evidence of additional fire involvement in the north wing at that time.

West Side Operations

Engine 5 forced entry to the bakery area through the rear door and found no evidence of fire in this area. There was no smoke or heat and everything appeared to be normal in this area. The crew then raised a ladder to the roof of the west wing and took a l-3/4 inch line to the top of the ladder. They did not go onto the roof because of a downed power line that was in their path. The hoseline was operated from the ladder to knock down the fire on the exterior of the west wall.

When the Captain of Engine 2 was assigned as Division C, he directed his crew to advance a back-up line for Engine 5 and then to take another handline around the west wing and into the north wing. They entered through the doors to the lower level of the north wing and found the area charged with smoke, but no evidence of fire or elevated temperatures.

Rooftop Operations

The crew of Ladder 1 went to the roof and found fire lapping overu and onto the roof from the west side. They initially selected a point to open the roof toward the west side of the building, but the heat was so intense that they had to back away before the hole was cut. They decided to move back several feet to the east and to begin a north-south trench cut to reduce the risk of interior fire spread from west to east. They also asked Division B to send up a hoseline to protect them and to control any fire spread on the roof covering. The two crew members from Aid 5 (a BLS ambulance) were sent to the roof with an additional hoseline.

Ladder 1 was joined on the roof by the crew from Ladder 3 and both crews worked on the trench cut. The progress on this cut was slow because of the two layers of roof boards, one on top and one below the roof joists. They had to cut the roof covering with a chain saw and strip away the top layer, then reach down between the joists with the chainsaw to make a second cut through the lower layer of boards, then finally remove the lower boards to ventilate the interior.

Continuing Interior Operations

The initial entry crews depleted their air supplies and had to come out to replace their air cylinders between 1920 and 1925 hours. Division B requested additional companies from the Incident Commander to rotate on the attack lines as the companies came out of the building. Ladder 7, which had responded on the special call, was directed to report to Division B and was assigned to take over one of the interior attack lines. Engine 36 and Ladder 3 were also assigned to take turns on the interior attack lines.

While en route to obtain a full air cylinder from his apparatus, the Lieutenant of Engine 13 observed the hoseline that was being operated by Engine 5. He stopped at the Command Post to express his concern that this line was pushing the fire toward the interior attack crews. The Incident Commander contacted Division C and reemphasized that the operation of exterior lines must not oppose the interior operation; he then left the Command Post momentarily to personally check on this operation. He returned to the Command Post after confirming that the exterior operation was not causing a problem.

When the Lieutenant of Engine 10 came out of the building to change cylinders, a few minutes later, he reported to the Incident Commander that this structure was the one they had been warned about as an arson target and to be sure that the investigators had been notified. (The on-duty investigators were already on the scene and had initiated their investigation.)

After changing air cylinders, the crews of Engines 10 and 13 reported back to Division B and were sent back into the building to resume the interior attack When they reentered they noted that the atmosphere was much cooler and they could stand-up to walk around. The roof had been vented by this time, which relieved the heat. The building was still heavily charged with smoke and they had difficulty navigating, however, they did not find any significant interior fire involvement.

Engine 13 advanced all the way to the west wall and into the lunch room, where they found that the fire had burned through the wall from the exterior. They conducted overhaul in this area and attacked some fire that was visible through the hole in the wall. Ladder 7 advanced a line toward the middle of the floor area searching for fire, while the Lieutenant and one crew member from Engine 10 were working to their right with the third line.

Basement Fire Discovered

The crew of Engine 2 had been assigned to look for additional areas where the fire could extend to the north and west. They located an opening in the north wall of the west wing that provided access to the interior loading dock. (The opening was an old doorway that had been covered-over, but the covering was loose.) They advanced their line through this opening and used a step ladder that happened to be there to drop down to the loading dock.

When they reached the loading dock they found the sliding fire door leading into the storage room partially open. The interior of the storage room was fully involved in fire; however, no smoke or flames were coming out of the doorway. The large fire was drawing air in through this opening.

The crew advised their Captain (who was in charge of Division C at that time) of this discovery and discussed the possibility of launching an attack into the fire area from the west side. They were aware that the attack plan had been defined as east to west and that their assignment was to prevent further extension to the west. Following this plan they took positions to hold the fire at the loading dock, in anticipation of an interior attack coming toward them.

Battalion Chief 2 had arrived and reported to the Incident Commander at approximately 1925 hours. He was briefed on the attack plan, emphasizing that the objective for units on the west side was to prevent extension while the interior attack was made from east to west. He was then assigned to relieve the Captain from Engine 2 as Division C.

Battalion Chief 2 went to the west side of the fire building, was briefed on the situation by the Captain of Engine 2, then took charge of Division C. Engine 25 was assigned to report to Division C as a relief company.

At approximately 1930 hours it was recognized that the division designations were incorrect. The east side of the fire was redesignated as Division C and the west side was redesignated as Division B.

Safety Officer

The Deputy Chief of Training and Safety had responded from his residence on the working fire notification and assumed the role of Incident Safety Officer at 1922 hours. He initially conferred with Division B (Battalion Chief 5), verified that accountability procedures had been established, and evaluated the interior conditions from the east side. By this time the roof had been opened and there was no indication of a heated interior atmosphere. He noted that the interior was heavily charged with smoke and expressed concern to Division B that there could be a concealed fire that might suddenly break out or flash over. He emphasized the need to prepare a 2-l/2 inch back-up line and to assign a crew to stand-by as a Rapid Intervention Team.

The Safety Officer then proceeded to the Command Post where he was briefed on the attack plan and reported his observations to the Incident Commander. He then continued around to the west side to evaluate conditions. He entered the west wing through the bakery door and noted the absence of smoke or any indication of fire in the lower level. He also noted that most of the exterior fire, which had been evident when he arrived, had been knocked down by Engine 5’s hoseline.

He then encountered the Acting Assistant Fire Chief of Operations, who had arrived at the Command Post.

Assistant Chief of Operations

The Acting Assistant Fire Chief in charge of Operations had also responded from home on the initial report of a working structure fire in the International District. He approached from the north and parked his car northeast of the fire. From the comer he noted a strong thermal column rising from the rear portion of the structure. When he reached the building and looked in through the doors from the east side, he noted that the interior was heavily charged with smoke, but not hot. The inconsistency of these observations caused him to believe, that there must be a significant fire burning somewhere in the structure, but that it must be in a different part of the building or in a concealed space. He asked the Division B Chief if the building had a basement and received a negative reply—this caused him to suspect a cockloft fire.

He then proceeded to the Command Post, where he discussed his concerns about a concealed space fire with the Incident Commander. The Incident Commander had not received a report from the roof and was not aware of the progress that was being made on vertical ventilation. The Acting Assistant Chief recommended calling for a third alarm, anticipating an extended operation, and told the Incident Commander that he wanted to make a full personal reconnaissance survey before assuming command of the incident. The third alarm was requested at 1932 hours.

The Acting Assistant Chief of Operations then encountered the Deputy Chief of Training and Safety, who reported that there was no evidence of fire in the lower level and that he had seen no major problems on the west side of the fire. The two of them returned to the east side and went to the roof to evaluate conditions, looking particularly for evidence of a cockloft fire.

On the rooftop they noted that a moderate amount of smoke was coming from the vents. This observation was inconclusive with respect to their suspicion that there could be a significant fire in the cockloft or in some other concealed space. They recognized that additional ventilation would be needed to either locate a concealed space fire or confirm that there was none.

The Acting Assistant Chief contacted the Incident Commander at 1936 hours to notify him of the need to assign a division supervisor to the roof. The Captain of Ladder 3 was assigned this responsibility pending the assignment of a command officer.

Floor Collapse

At this time the three interior lines were being operated by Engines 10 and 13 and Ladder 7. The Lieutenant and three firefighters from Engine 13 were operating in the northwest comer and the lunchroom. The Lieutenant and one firefighter from Engine 10 were working in the north half of the ground floor, while the Lieutenant and three firefighters from Ladder 7 were near the middle of the large space. All of the crews were in dense smoke, but the atmosphere was cool and there was no visible fire. The Lieutenant of Engine 10 and his partner briefly encountered the crew of Ladder 7, then disappeared back into the smoke.

Seconds later the building rumbled and flames erupted from the basement as the floor began to collapse. It appears that the “pony wall” failed, dropping the ends of the floor joists. Sections of the wood and concrete floor hinged down into the basement. The flames coming from the basement spread across the underside of the roof and the contents of the ground floor began to ignite in a rapid flashover sequence.

Two firefighters from Engine 13 were in the lunchroom and heard their Lieutenant shout ” …Let’s get out of here!” as the floor began to drop. The two firefighters were able to go out through the hole in the wall and onto the roof of the west wing. The Lieutenant and the other firefighter are believed to have fallen into the basement as one of the first sections dropped.

The Lieutenant of Engine 10 and his partner became separated as the floor collapsed. The firefighter was able to make his way back to the door and out, while the Lieutenant dropped into the basement.

The crew of Ladder 7 at first believed that the ceiling must have collapsed as flames spread across the open area over their heads. The Lieutenant opened the nozzle, attempting to cool the overhead, but the water stream immediately turned to steam. The four crew members began to follow their line back toward the door in single file as intense heat radiated down on them. They did not realize that the floor was collapsing until they encountered flames coming up through a large opening, almost directly in their path back to the doorway.

Two of the firefighters and their Lieutenant managed to scramble to the door and outside, passing within feet of the opening. When they reached the exterior they realized that the third firefighter was no longer with them. The missing firefighter had been first in the line as they were trying to find their way out and he either fell into a hole or dropped into the basement as a floor section collapsed under him.

All of the seven firefighters who escaped were burned. The majority of the bums were to their necks and ears. The Lieutenant of Ladder 7 had additional bums to his wrists and one hand.

Accountability

It was evident within seconds that something was going wrong; however, personnel outside the building were not immediately sure what was happening. Hot, heavy smoke and some flames began to issue from the doors and out through the hole in the roof. On the east side of the building firefighters began to scramble out the door with their protective clothing smoking. It took almost a full minute before the Lieutenant of Ladder 7, the last to escape, came out of the building.

On the west side the two firefighters from Engine 13 suddenly appeared at the top of the ladder, having crossed the roof of the west wing, reporting that their Lieutenant and another firefighter were missing.

The radio came alive with messages to abandon the building and the evacuation tones were sounded by the Incident Commander. The Communications Center reported that an emergency notification signal was being received from one portable radio, then from a second radio. As soon as he could get outside and account for his crew, the Lieutenant of Ladder 7 transmitted a message that one of his crew members was missing.

It took only a few minutes to account for all of the crew and crew members and to confirm the identities and last known locations of the four missing personnel. Crews outside the building were quickly organized to operate streams into the opening in hopes of protecting the firefighters who believed at that point to have fallen into the basement. Search and rescue plans were developed, based on their last known locations.

Rescue Attempts

The Acting Assistant Chief of Operations assumed command of the incident and assigned the Acting Deputy Chief to manage the Operations Section. The 4th and 5th alarms were transmitted for additional resources and four additional medic units were requested.

Two Rescue Branches were established, one on the east side to conduct rescue operations on the upper level and one on the west side to make a similar effort in the lower level. The floor collapse was determined to involve only the sections immediately south of the interior fire wall, so there was a possibility that some of the missing firefighters could still be on the upper level. After evaluating structural conditions crews were reassigned to the roof to provide additional vertical ventilation.

The crews upstairs had very little success penetrating the structure, due to the intense heat; however, the crews in the basement made several entries including some deep penetrations into the rubble. With the openings in the floor above and in the roof the heat and smoke were venting and the rescue teams were able to work their way into the rubble.

Engine Companies 2 and 25 and Ladder 10 advanced hoselines into the storage area and attempted to move some of the debris, but they were unable to get through the combination of burning contents and materials that had fallen into the basement. They then went in through the bakery area, which had also become involved in the fire, and worked their way all the way to the east wall. At different times they believed that they could hear PASS units sounding or SCBA low pressure alarms, but they were unsuccessful in locating any of the missing personnel.

The rescue attempts involved a very significant personal risk to the rescuers; however, they were well organized and very conscious of conditions. It was later determined that the rescuers came within a few feet of two of the victims, but they could not be located in the rubble and probably could not have been saved at that point.

The rescue efforts were discontinued when it was determined that the risk of additional structural collapse was imminent. At this point victims had been missing for over an hour and any hopes of finding them alive had been given up. All personnel were withdrawn from the structure for a second time and defensive operations were conducted, using master streams to control the fire.

Body Recovery

Body recovery efforts were initiated the next morning, in coordination with an intensive fire cause investigation. The bodies were believed to be in the storage room, which was also the suspected area of origin of the fire. This situation necessitated a very slow and deliberate removal of the debris to recover and document evidence, while also searching for the bodies. The structure had to be partially demolished and parts had to be braced before entry could be made. Two bodies were recovered during the first day, one on the second day, and the last body was not located until the third evening, 72 hours after the fire was reported.

All four firefighters are believed to have died from asphyxiation after running out of air or losing the integrity of their SCBAs when they fell. Two were incapacitated and died where they fell, while two had managed to move a considerable distance from the points where they are believed to have fallen into the basement.

All four of the firefighters were equipped with PASS devices and all four also had portable radios. The emergency buttons on two of the radios had been activated and two of the PASS devices had been activated. The other two PASS devices were found with the switches in the OFF position.

ALSO

- The Fires That Forged Us: Cherry Road Fire

- The Fires That Forged Us: The Watts Street Fire, New York City

- The Fires That Forged Us: Three Keokuk (IA) Firefighters Die in Rescue Attempt at Fire

- The Fires That Forged Us: “Black Sunday” and the FDNY

- The Fires That Forged Us: Six Kansas City (MO) Firefighters Killed in Blast

- The Fires That Forged Us: The Yarnell Hill Fire

- The Fires That Forged Us: Sofa Super Store Fire